Some Observations on the United States Presidency

By Gerhard Casper

Since my main academic field is American constitutional history and American constitutional law, especially the separation of powers, I am, these days, frequently asked about the extent of presidential powers under the Constitution.

The Founders were determined to separate power. They considered the separation of power—it is useful occasionally to employ the singular—a condition of liberty. They created a system of government that characterized by a vertical and horizontal separation of powers. By vertical separation of powers, I mean federalism. The United States constitution enumerates the powers of the federal government and reserves all other powers to the states. In the course of American history, especially during the New Deal, the vertical separation of powers has been considerably weakened, on account of ever broader interpretations of the various powers allocated to the federal government. Today, very few human activities, previously the domain of the states, cannot be regulated by the federal government if it so desires.

By horizontal separation of powers, I mean the fact that the Constitution, as concerns the federal government and beginning with Article I, differentiates among “all legislative powers herein granted,” “the” executive power and “the” judicial power. The sequencing suggests a preeminence of Congress.

Article II begins with the words “The executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America” and lists various presidential powers (such as commander-in-chief). The dispute over whether the particular wording of the vesting clause in Article II was designed to add “executive” powers not specifically enumerated is textually unresolvable. My own opinion is that the Constitution makes most sense if enumerations are read as being exhaustive. At the time of the Constitution’s adoption, there existed a widespread fear that the presidency might be turned into a temporary monarchy or might fall into the hands of a Cataline or Cromwell. The President’s primary power is a duty: “[H]e shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”

The American system combines separation of powers with checks and balances. For example, the President has a veto over legislation that can, in turn, be overridden by a supermajority in the Congress. The Senate has to agree to senior appointments in the executive branch or consent to treaties. The President can repel sudden attacks on the United States, but the power to declare war is reserved to Congress.

As the history of the twentieth and twenty-first century shows, in spite of the constitutional arrangements, many American presidents have claimed the power to act unilaterally in military and other matters. As the war in Vietnam ended, Congress, in 1973, tried to rein in presidents with legislation known as the War Powers Resolution. It has not been very effective. For instance, this spring Congress passed a resolution attempting to end American support for Saudi Arabia in Yemen. It was vetoed by President Trump in part on account of its “weakening” of alleged “constitutional powers” of the president.

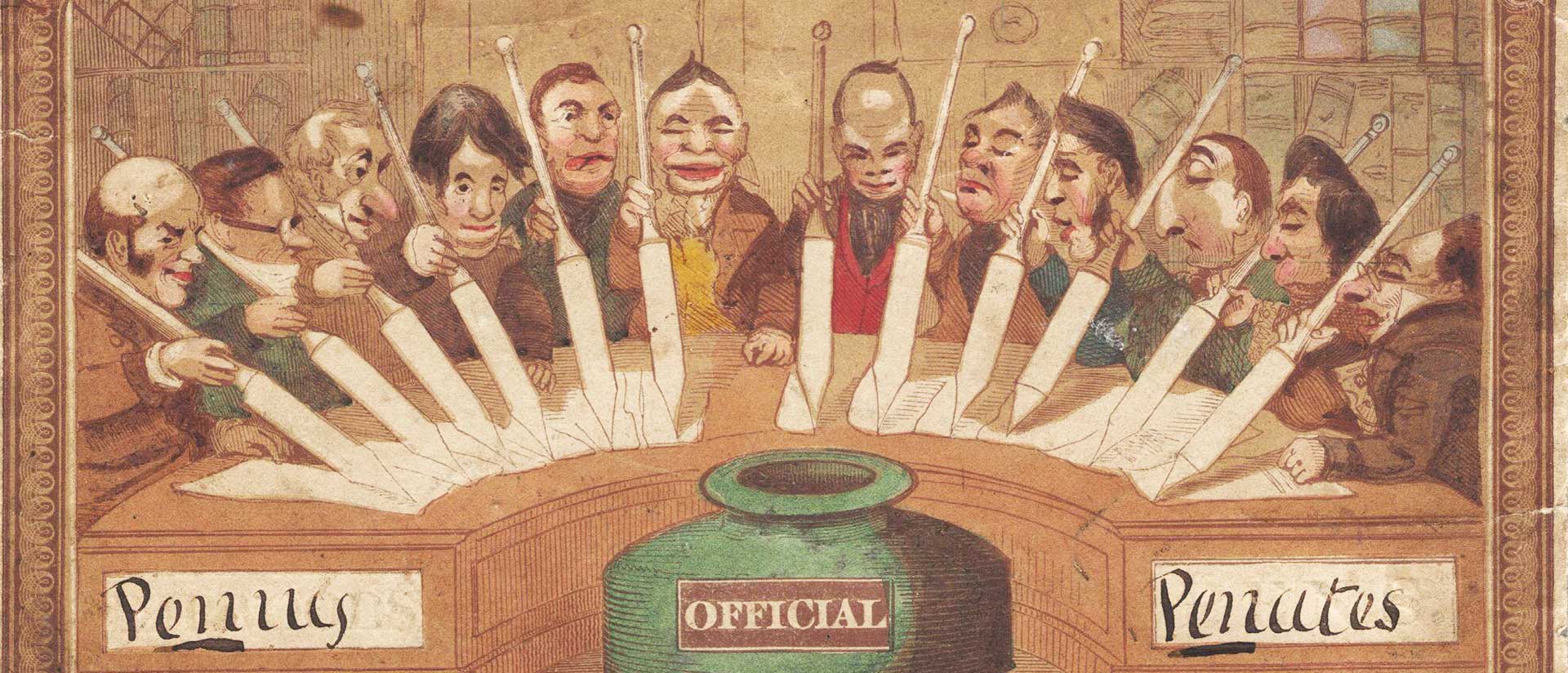

However, President Trump is by no means the first President to believe that he has a mandate to act independently of the Congress. One hundred years ago, Max Weber saw the United States as an example of “mass democratization.” “Every kind of direct popular election of the supreme ruler and, beyond that, every kind of political power that rests on the confidence of the masses and not of parliament … lies on the road to these ‘pure’ forms of Caesarist acclamation. In particular, this is true of the position of the President of the United States, whose superiority over parliament derives from his (formally) democratic nomination and election.”

While constitutionally the American president cannot claim superiority over the Congress, the Congress has considerably strengthened the executive by delegating, over the decades, ever more powers to the president. For example, President Trump’s trade wars are largely justified by invoking authorities that Congress delegated in the interest of “national security” and the like.

Article II provides that the President shall “from time to time” give the Congress information about the state of the union. Ironically, it is through the de facto power to speak, not just “from time to time” but endlessly, and provide information as well as misinformation, that the current President is causing much mischief. Simply through talking, by words alone, the President is subverting civility, race relations, foreign relations, the rule of law, science and scholarship.

Gerhard Casper is trustee-in-residence at the American Academy in Berlin during the 2019 fall semester.