Who “We” Are

A conversation about shifting power and perspectives

Academy president Daniel Benjamin spoke with Anne-Marie Slaughter, CEO of the public policy think-tank New America, about how the United States can rise to meet the world’s most urgent political and economic challenges—and how to strengthen democracy at home.

Daniel Benjamin: Some commentators say we live in a multipolar world, citing China’s economic rise, Russia’s continued influence, and the relative size and wealth of the European Union. Yet the United States’ gross domestic product and military spending continue to dwarf those of all other countries and blocs by orders of magnitude. Do you believe that we live in a multipolar world?

Anne-Marie Slaughter: I prefer the formulation used by Indian Minister of External Affairs S. Jaishankar, who says we live in a “multi-aligned” world, in which countries are free to pursue their “preferences and interests” by engaging and even partnering with others that may be at odds with one another. As an example, India has drawn steadily closer to the US, Japan, and Australia through the increasingly formalized Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, but has also increased its oil imports from Russia, which is now its top supplier.

During the Cold War, India was one of the founders of the Non-Aligned Movement, a grouping of over a hundred mostly developing countries that focused, as the name suggests, on not aligning with either the US or the Soviet Union, or indeed with any specific power bloc. Multi-alignment is India’s declared policy as a great power, or certainly as an aspiring great power. Retired General David Petraeus recalled that shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, he told Jaishankar, who was then serving as India’s ambassador to the US, that as a member of the Quad, India must “make a choice between East and West.” Jaishankar responded, “General, we have chosen. And we have chosen India.”

China would describe its foreign policy in similar terms. It seeks to avoid “Cold-War thinking” and to align with many different groups of nations, including the EU, as its economic, political, and military needs dictate. Turkey increasingly fits into this category as well, even as a NATO member, as do Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Brazil, and even Mexico. These are all nations that the US often needs for various diplomatic purposes, such as the condemnation of Russia for the invasion of Ukraine, and yet has not been able to convince, much less compel, to support Washington’s position on issues ranging from sanctions against Russia to condemnations of China for human rights abuses.

The description of global politics by reference to the number of poles operating in the “international system” also seems very twentieth, or indeed nineteenth, century. As a measure of military and economic power during an era in which great power war was the chief danger to world security and prosperity, it signaled the relative stability or instability of the system as a whole. It was also the foundation of Kenneth Waltz’s theory of structural realism, with the great social scientific hope, in emulation of the natural sciences, that immutable laws of international relations could be deduced from the basic structure of the system.

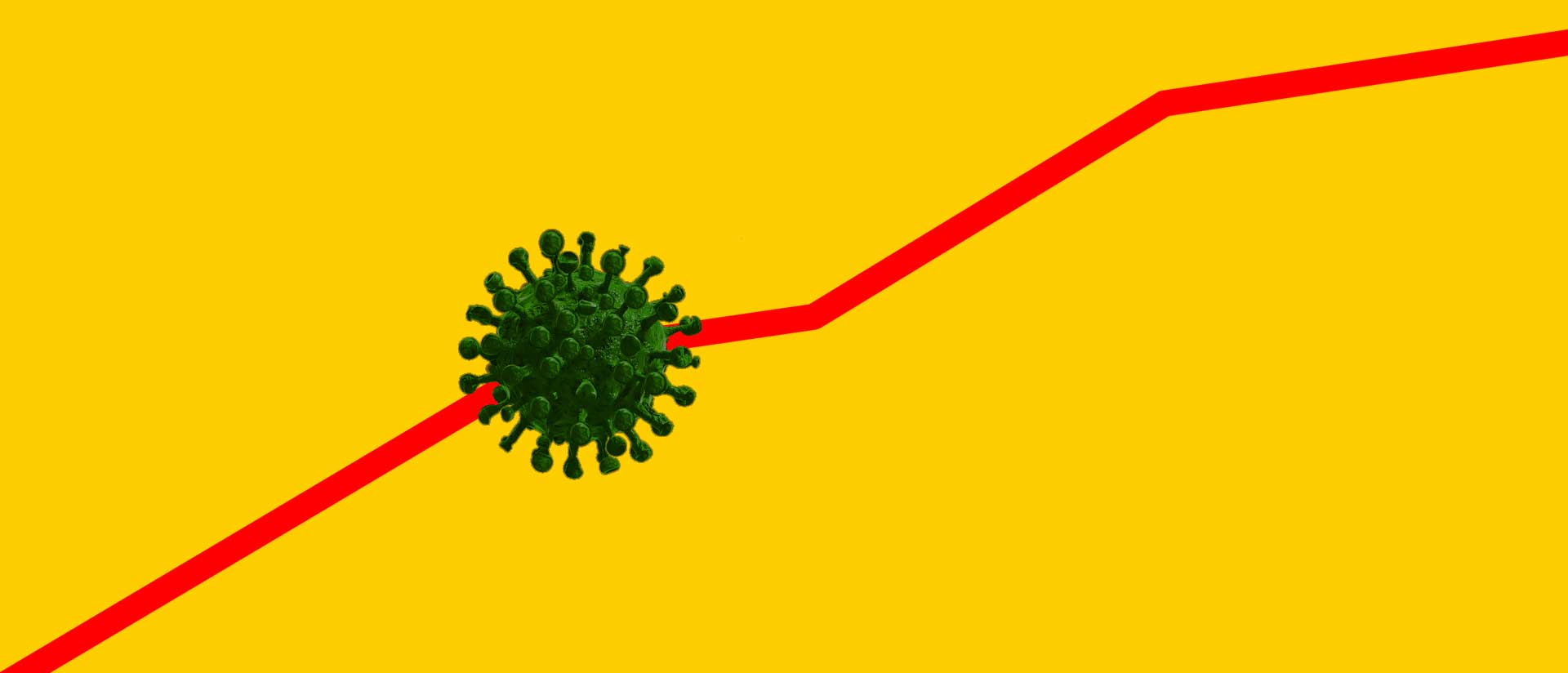

Yet where exactly does power in a unipolar system get you—even as the number one nation? It is certainly true that that the US spends three times what China or the EU nations do on its military. Still, the US has not achieved its goals in the last two wars it fought directly, in Iraq and Afghanistan, even against adversaries so much weaker on paper that they would not even be counted in the tabulations of military expenditure. The US, with all of its NATO allies and global partners, is providing indispensable military support to Ukraine to help it push back Russia. But it was unable to deter the invasion in the first place, and a positive outcome for Ukraine will be due as much to the determination and courage of the Ukrainians as to the size of the world’s greatest military arsenal.

The US, with all of its NATO allies and global partners, is providing indispensable military support to Ukraine to help it push back Russia. But it was unable to deter the invasion in the first place.

On the economic front, the GDP of the EU and of China are roughly twenty-five percent lower than that of the US, hardly an unbridgeable gap. The EU is China’s largest trading partner and the largest export market for some eighty countries. It is also the world’s greatest regulatory power, such that requirements imposed on goods and services for access to the EU market quickly go global, a phenomenon known as the Brussels Effect.

Overall, the complexity of the many global and geopolitical threats and challenges we face means that the measurement of power is often quite nuanced and tailored to a specific issue or set of issues. The US still has many global advantages and can certainly be indispensable in situations that require military might and technological prowess. The instability of its domestic political system and the ambivalence of many of its people toward global leadership, however, have given pause even to its closest allies in recent years. US leaders in every sector would do best to assume that they are operating in a world in which the outcome of power struggles is simply not predetermined, no matter how many poles there are.

DB: The US has deviated from its free-trade traditions by offering subsidies and tax credits to jump-start a long-overdue energy transition. This has angered European allies, who accuse the US of protectionism. Do you see that response as justified? And are you worried about the growing turn to protectionism as the US and Europe take more restrictive approaches on advanced technologies such as microchips, AI, and quantum computing due to national security concerns?

AMS: Many American trade- and foreign-policy experts are a little bemused to find themselves suddenly accused of protectionism by the EU, which from the US perspective has long fiercely protected its agricultural market and adopted behind-the-border health and safety measures that have effectively excluded US goods and services. That does not make US protectionism right, but it should open the door to dialogue about how best to revise the rules of the global trading system to strike a new balance between free trade, resilience to external shocks, and national security. I understand the disenchantment with globalized free trade that has taken hold on both the right and left in the US; it has sharply widened inequality and discredited the division between allocation and distribution that was the foundation of classical economics. Markets should not be opened without a strong set of protections designed to ensure that displaced workers not only have a financial safety net but also a real path to new jobs. On the other hand, given the relative wealth of the US and Europe, leaders on both sides of the Atlantic should be thinking hard about a fairer global trading system that continues the advances made by people in developing countries around the world during the heyday of globalization.

Balancing those national and global concerns is a national duty as an American. We proclaim not just national but universal values, a commitment to the equality, liberty, and rights of all humankind. That is a moral commitment, but also one that is very much in our self-interest. Rather than trading jabs with the EU about protectionism, we should be collectively engaging nations around the world to devise rules and decision-making procedures that work in the service of both trade and national development.

DB: Relatedly, the great energy transformation is underway and will alter our lives dramatically over the coming decades. What changes do you see ahead for society, politics, and economies in the Atlantic North? How will this differ for the Global South? How will adapting to climate change affect foreign policy, for example?

AMS: I honestly think that we are on the brink of an energy revolution that is as great as the discovery of carbon fuel. The combination of new energy technologies—not only those we can see, like hydrogen fuel cells and salt rather than lithium batteries, but also those we can only dimly discern, like fusion and quantum computing— means that we may be able to avoid the worst impacts of climate change and usher in an age of energy so abundant that projects like desalination at scale, and hence unlimited fresh water, become economically feasible.

But I see horror stories ahead as well. Books like Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace Wells and Ministry of the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson spell out doomsday scenarios in detail. As foreign-policy experts, we must continually remind leaders and the public that climate change is a greater existential threat to humanity than anything else, particularly alongside the disease, water and food shortages, and massive migration it will bring. Regardless of how bad any particular conflict or interstate rivalry may be, we simply have to keep insisting that global warming is as urgent and important as any war.

Regardless of how bad any particular conflict or interstate rivalry may be, we simply have to keep insisting that global warming is as urgent and important as any war.

Equally important, this is an international problem where the Global North simply cannot go its own way, developing and deploying new technologies decades or even half centuries before the Global South. If we take that approach, as we have in centuries past, we will all suffer the consequences.

We need to focus on new technologies and bring them into use as quickly as possible, and at the same time subsidize or mandate conservation, energy efficiency, and transition to less carbon-intensive energy use now. We should engage mayors, governors, civic groups, corporations—any actors who have the ability to change behavior themselves or the levers to change it in others.

DB: You are working on a project about care and capitalism, asking what would happen if US domestic policy and economics were better able to combine the two. It seems that European countries have been doing this for decades, particularly in removing much of the profit motive from areas such as healthcare, education, and important media outlets. Do you think this is possible in America? What needs to change?

AMS: Europe definitely strikes a better balance than the US between the deep value of human connection and the riches that can flow from individual human striving. Yet even European systems do not start from a point in which connection and separation, care and competition, belonging and longing, are treated and valued equally. What needs to change is our conception of human nature, of who “we” are and what “we” want. I think that is possible as long as the “we” who sit around decision-making tables of every kind and at every level, actually reflect the people—of all different backgrounds, cultures, classes, races, ethnicities, and other differentiating categories. I have been thinking and reading about these issues for nearly a decade; my guess is that I will need nearly a decade more before I have more precise and testable answers. But lots of other thinkers are pushing in the same direction.

DB: The past decades have seen a rise in illiberal, antidemocratic movements around the world, and there is a widespread sense that democracy in America is not nearly as secure as it once was. How seriously do you interpret the threat to American democracy? And what do you think the US and international NGOs can do to strengthen democracy globally?

AMS: The threat to American democracy is graver today than perhaps at any time since the Civil War. Politically, we are two nations that are increasingly segregated from one another in the places we live, the schools we attend, the places we worship, and the news we consume. We are also a nation undergoing extraordinary demographic transition. After four hundred years of a dominant white majority, we will become a plurality nation, in which no ethnic or racial group has a majority, within the next two decades. No democracy has ever experienced such a transformation. The social and cultural turbulence is manifest in our politics, exacerbated by enormous technological and economic upheaval and the realization that we are at the mercy of global threats that we cannot address by isolation or invasion.

The threat to American democracy is graver today than perhaps at any time since the Civil War.

The most important thing that pro-democracy groups can do in the US is to outlaw and prevent political violence and find ways, beginning at the local level, to bring people together around a set of positive aspirations. We will not find our way across current political chasms. But those divisions must be counterbalanced by a renewed sense of common interest and vision for a better future for all Americans. We should devote as much energy as possible to structural reform of our electoral systems, at the state and national level, to enable multi-party systems beyond just two dominant parties. That model is increasingly unworkable as we become increasingly diverse. Globally, we should be learning as much as we can from deeply divided polities.

The US has been here before. Indeed, many African Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans and others would say that race and ethnicity always dictated the circumstances of their lives and structured politics at every level in ways that white Americans are only beginning to understand. We have a potential future in which we can reflect and connect the world, using the kinship ties and cultural knowledge of our people to create political and economic opportunity at home and abroad. But we could also find ourselves in a second civil war.

This interview was conducted in July 2023 and appears in the Berlin Journal 37 (2023-24).