Death and the Miner

The afterlives of gold in South Africa

By Rosalind C. Morris

For more than a century, the gold mines of South Africa were the sparkling center of a nation. Today, they are closing. In their ruins, moving along the more than 10,000 kilometers of underground tunnels that traverse the earth beneath the Witwatersrand—a 56-kilometer rocky scarp jutting 200-meters out of the earth—itinerant migrant miners called zama zamas scavenge for gold.

Historically, mining in this area depended on capital-intensive mechanization, including drilling, automotive and electrified rail transport, large-scale dewatering and oxygenation, as well as cyanide and mercury-based communition processes and industrial smelting. Zama zamas perform all of these functions manually—using only picks, hammers, battery-operated headlamps, and protective clothing woven from jute sacks. Without the assistance of mechanized carriages, they slide down the shafts, following old and fraying cable. Upon finding a potential vein in the rock, they assay samples by panning, and use small amounts of dynamite to blast rock that they carry on their backs in bags that once held rice or corn meal. The men stay underground for days, weeks, even months at a time. Working in small groups of friends and relations who share a language, they sleep and eat, work and rest, listen to music stored on cellphones, smoke cigarettes, and recount stories of home, all while asking their ancestors for help in finding fortune. The word “zama” means to try in isiZulu. “Zama zama” means “to keep on trying,” but also “to gamble.” Zama zamas are those who risk everything to survive.

Above ground, women break the rock with hammers or other rocks. They then grind the broken stone into powder, which is mixed with water and poured over improvised sluicing tables from which the men gather visible nuggets and flakes before sifting the runoff. Finally, this is processed with mercury, which the men pass between their bare fingers, while observing the darkening color that betokens amalgamation. The residual sluice constitutes payment for the women, who then reprocess it. At the end of these gendered activities, which differ in both the time they take and the amount of gold they generate, both men and women sell tiny nuggets to local middlemen, who keep track of spot prices on the international commodities market, and pay in cash. Whether sold independently or brokered by criminal syndicates, the gold will travel along the capillary networks that extend from Johannesburg to China and Pakistan, the US and Europe—where most of it will become jewelry.

Most zama zamas are from Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Lesotho, and Malawi. They travel the same routes as have formal miners since the colonial era, when the Chamber of Mines and its labor recruiting organizations sought African workers for the most arduous labor underground. But today’s zama zamas are mainly undocumented migrants, whose illegalized status excludes them from public education, healthcare, and the rights that citizens expect. The objects of fear and xenophobic violence, they are doubly displaced, hyper-visible in the media and invisible as actual subjects of history.

Why make this arduous journey and expose themselves to such terrifying risks? Quite simply, the extreme poverty that they have left behind exceeds even that of the ruins in which they now seek leftover gold. “The mouth is dreaming,” say zama zamas, when describing the hunger that is their constant companion. Along with the threat of accident and the toxicity of their environment, these men and women are driven by daily need to flirt with death in order to defer it. Nor is the only threat below ground. The powdered rock clouds in the air enters the lungs of the women—and the infants strapped to their backs—just as the dust that rises from the blasted rock enters the lungs of the underground miners. The Oracle of Death writes her prophecy in the lines drawn by sweat or tears on their dust-powdered faces.

During more than two decades of research around the gold mines of South Africa, I have, perhaps improbably, come to see this underground world as a negative image—in the photographic sense—of the Parisian shopping arcades about which Walter Benjamin wrote nearly a century ago. The vaulted ceilings of the tunnels are made possible by the materials and technologies that also enabled the arcades’ construction. But whereas the arcades of Paris were theaters of display value, where commodities were illuminated as future relics of fashion, the value on display underground is that of technology itself: the incredible feats of engineering that have enabled mining four kilometers below the surface.

But something else links these distant worlds: the economy of the arcades was not merely one of mass reproduction, it was a system in which even waste could be a source of value—and “mined” by the ragpicker. Now, in the ruined gold mines of southern Africa, the ragpicker finds an uncanny doppelganger in the zama zama, whose dusty visage they liken to a ghost. They haunt the landscape where industrial reclamation activities devour the mine dumps: each an emblem of gold-mining’s afterlife.

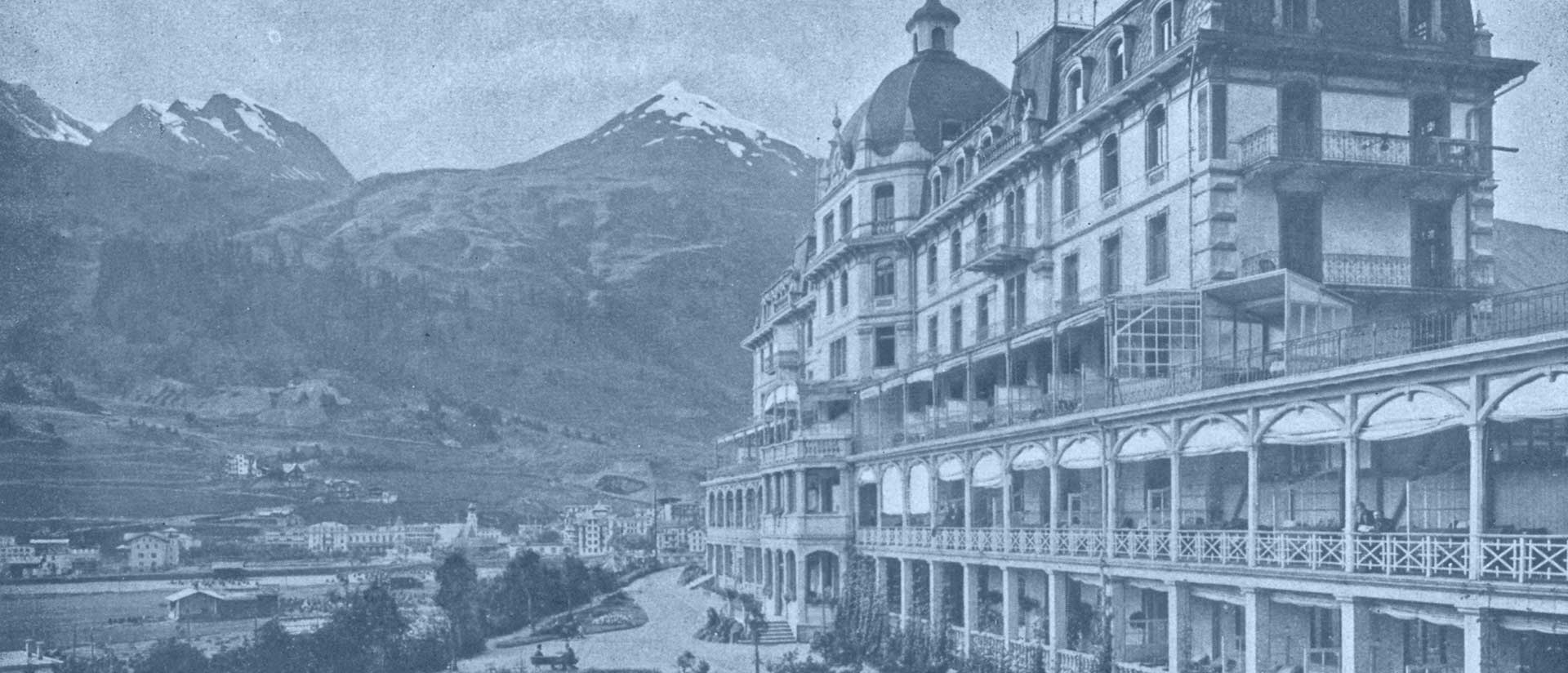

Benjamin’s milieu provides unexpected parallels for the mine-made world, but it also made powerful contributions to it. Three of the figures behind the largest mining companies in the region, all created in the last decades of the nineteenth century, were German born. Julius Wernher, a Protestant mining engineer from Darmstadt, formed Wernher Beit and Co., with Alfred Beit, a German-Jewish businessman from Hamburg, who started out in real-estate speculation before partnering with Cecil Rhodes in the diamond and gold industries. They created the Wernher-Beit-Eckstein group of companies after joining with the son of a Lutheran pastor named Hermann Eckstein, a financier from Hohenheim, who acted as the first president of the Chamber of Mines.

It is in the ruins of one of the mines founded by Wernher, Beit and Co., that I have been making a film with and about migrant miners. The images in this portfolio are from a documentary project entitled “We are Zama Zama,” which I have been making with South African cinematographer Ebrahim Hajee and three zama zama miners: Rogers “Bhekani” Mumpande, Darren Munenge, and Prosper Ncube. Our shared ambition is to create a documentary testimony to the lived experience of this marginal community in a manner that makes the zama zamas’ risk-filled lives comprehensible.

The project also responds to the intensifying “problem” of migrancy today. As walls—both figurative and actual—are being erected around the world to keep economic migrants from escaping their poverty, the iconography of migrancy in the Euro-American media is increasingly limited to the spectacle of the Mediterranean. While important, the privileged iconography of the Mediterranean risks a too-narrow perception of migrancy as a crisis of and for Europe. Yet, much of the migration born of poverty in Africa takes place within rather than as a movement out of the continent.

In addition to local problems, which range from corruption to warfare, this African crisis also has European history: not only the legacy of resource-based colonialism (of which Wernher, Beit, and Eckstein were a part), but the histories of foreign aid that generated dependencies now being severed. As global neoliberal governance leads to the demand that decolonizing states cut back on their own social-grants programs, a rising tide of populist nationalism calls formerly colonizing states to reduce their foreign- aid contributions. As a result, vast zones of uninhabitability are emerging, a situation that will only worsen with changing climatic conditions.

Making a film about undocumented migrants is not an answer to these problems. But it is an effort to open conversation with a different lens and a widened focus. To ask different questions about the causes and possible means of redress demanded by this complex problem requires, firstly, that the lives lived in industrial modernity’s ruins be recognized in their fullness. The stories of my film, of the ruined mines, and of the migrants who gravitate to those now-abandoned temples of technology and international financial capital, are stories of the future: dream images that the Oracle of Death demands we confront.