Revolution and Modern Greece

The Battle of Dervenakia, 1822

by Yanni Kotsonis

“Where is Dervenakia?” I asked out of my car window, to a woman waiting on the side of the road, next to an abandoned railway station. It was April 2018, and I was in the northern Peloponnese. I had left the highway somewhere between the modern city of Corinth and the site of ancient Mycenae.

“I don’t know, probably that way,” she said, as she motioned beyond the railway.

Ten minutes later, still lost, I asked a family standing next to an ancient Toyota pickup truck, only to realize, to my embarrassment, that I had interrupted a man praying on a rug—probably Syrian refugees. After a few more inquiries, I was eventually answered, accurately, by a boy of about 12 working at a gas station, in the village of Aghios Vasilios (St. Basil).

“Aghios Vasilios, of Corinthia,” he knowingly specified.

“And you? Where are you from?” he asked.

“I live in New York, of America.”

He grinned and then sent me back in the direction of the abandoned tracks. I followed a one-lane road with hairpin turns and ascended terraced cliffs with gradient levels until I reached the top. And there I was, in a parking lot big enough to accommodate busloads of schoolchildren and a multitude of officials’ cars when they come for commemorations.

The central attraction is a statue of Theodoros Kolokotronis, the Christian commander at the Battle of Dervenakia and overall military leader of the Greek War for Independence. From this height I could clearly see the narrow passes where the Battle of Dervenakia took place, during a hot summer and autumn of 1822.

Nearly all Greeks have heard of the battle, when Christian irregulars (a military outfit separate from a formal, national one) defeated—actually, annihilated—a much larger Ottoman army. The Christian uprising was a year old, and the battle ensured that that rebellion would continue and become a revolution. Rebellions and uprisings were common in the Ottoman Balkans, an occasion to rearrange local relations of power and redistribute privileges among the Muslim and Christian notables and armed clans. But the Battle of Dervenakia and the Greek Revolution more broadly were something new for the region: Ottoman Christians who began to call themselves Greeks faced Ottomans whom they called Turks. What had been a confessional marker became a national divider. Its traces can be seen in the composition of the Balkans to this day.

Modern Greece was a nation founded on religious identification—Orthodox Christianity—and was the model for future Balkan revolutions that created a neat Muslim-Christian binary out of the ethno-linguistic mix of the Empire. In this new alignment there was an Ottoman legacy: religion had always been used by the Ottomans as a marker of status. But there was something European, too. The European powers acquiesced to Greek independence because it was a Christian movement, and royal courts since the Congress of Vienna, in 1815, had been defining Europe more and more starkly as Christian. On this basis, between 1819 and 1823 the European Powers put down liberal revolutions in Spain, Naples, and Piedmont, since each challenged the absolute power of Christian monarchs. By the end of the decade these same powers recognized Greek independence and created the Kingdom of Greece, acceptable because it overthrew a Muslim ruler and would be ruled by a Christian king. The creation of Greece thus created a new boundary between Christian Europe and Muslim non-Europe that is still patrolled and reinforced today. And these new and stark lines of distinction were marked in blood on a small piece of land in the corner of the Peloponnese in 1822. But how?

Modern Greece was a nation founded on religious identification—Orthodox Christianity—and was the model for future Balkan revolutions that created a neat Muslim-Christian binary out of the ethno-linguistic mix of the Empire.

The statue of Commander Kolokotronis is gazing in the direction of a gorge, where two hundred years ago he organized a force of roughly 2,500 fighters upon these cliffs and terraces. An Ottoman army over ten times larger, circa 30,000 troops, had descended from the north across the narrow isthmus of Corinth, connecting the Peloponnese with the Balkan peninsula. Their mission was to put down a Christian uprising that was now over a year old. The soldiers were tired, having quashed the rebellious Ali Pasha earlier in the year, in the northwestern Greek city of Yanena. Ali Pasha was the influential Ottoman-Albanian ruler of the Epirus region, and his attempted break away from the empire resulted in his besiegement, defeat, and, eventual assassination, in 1822.

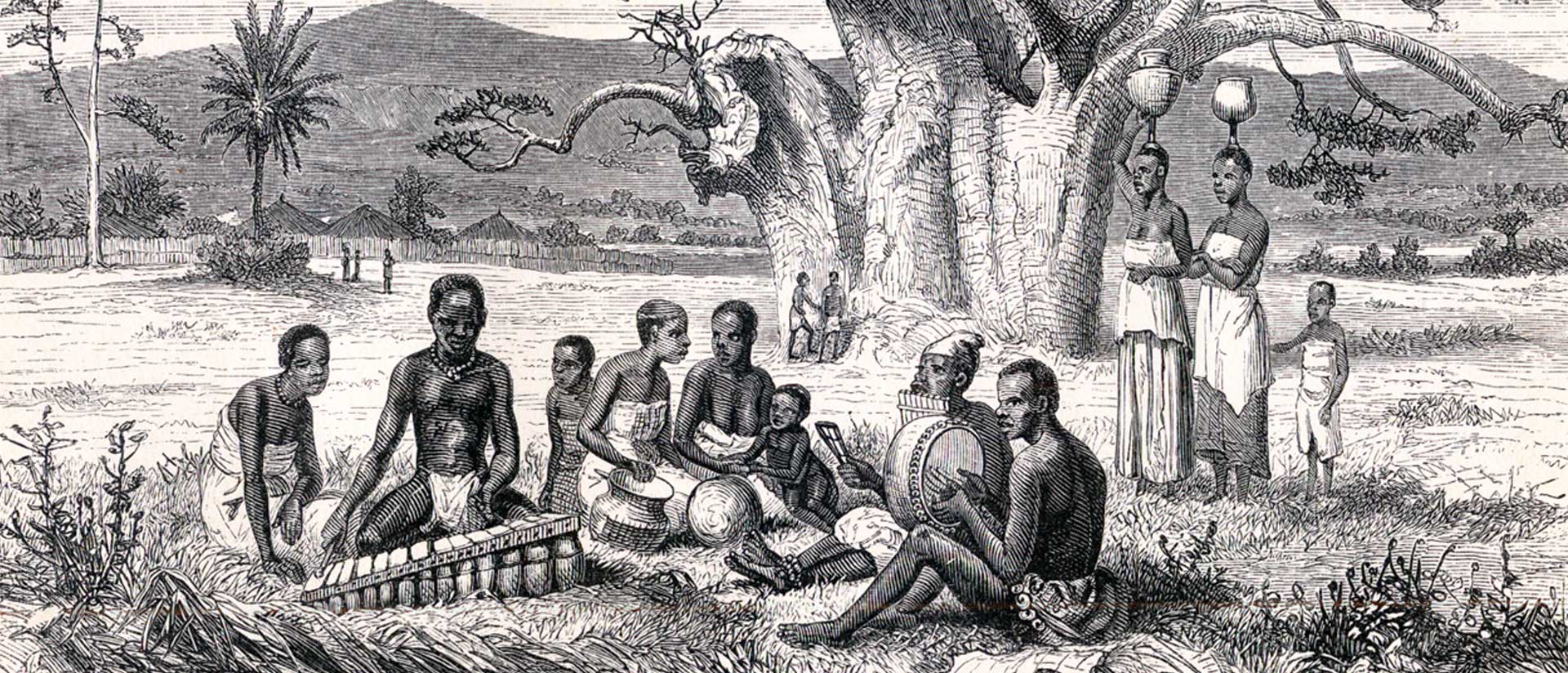

When the Ottoman irregulars turned their attention to the Peloponnese, they were reinforced by Albanian and Bulgarian irregulars, and also Greek-speaking mercenaries. The Greek forces were homogeneous, a glimpse of the future nation; the Ottomans were imperial, multilingual, and multiconfessional, a legacy of a declining empire. The Greek strategy was to defend a discrete territory, the Peloponnese—along with a confessionally homogenized population.

But Kolokotronis had a tactical mind. Looking down the gorge, one quickly understands why he chose it to make his stand—and why it was called the “Battle of the Little Passes.” (A mountain pass is a derven in Turkish, hence dervenakia, “little passes,” in Turko-Greek.) On their way from the plains of Argos to the Nemean plains, the Ottoman army was forced, by a series of Christian fighters, to funnel their lines into one of these passages. They were ultimately reduced to a single pass in single file, surrounded by steep hills and cliffs. Under such conditions, their numbers would matter less; their cavalry and artillery became useless. Moreover, for an invading army, the Ottomans were going the wrong way, north back to Corinth rather than south toward Nafplio. This was not part of their plan.

Having come down from the mainland, their commander—Mahmout Ali Pasha of Drama, or just Dramalis to the Christians—was to lead them to Nafplio to the south, the principal town of the eastern Peloponnese, stopping for supplies in Argos. Ultimately, Dramalis was to take Tripolitza (Tripoli) on the central plateau and crush the Christian rebellion in the whole Peloponnese. It was well understood that slaughter and enslavement awaited the locals before their formal submission; the Ottoman army was already marching with columns of slaves. This campaign was to be both a reconquest of space and a showing of irresistible Ottoman power.

Since the Christians had rebelled, they had lost the protection of the Sultan and could be killed, enslaved, or dispossessed. But Dramalis, a stranger from the north with an army gathered from afar, did not know the terrain. He followed routes without water, to towns already burned and depopulated by both Christian rebels and Muslim avengers over the previous year. He trudged past crops deliberately burned by Kolokotronis’s men, all during the hottest month of an unusually hot year. Reaching Argos, they found cinders, poisoned wells, and none of the food they thought was there. The Turkish mercenary Deli Mustafa, on horseback since Anatolia and Yanena, wrote in his memoirs that he was afraid of Kolokotronis, about whom he had heard gruesome stories long before crossing the Isthmus, but he was more afraid of dying of thirst. He and his fellow fighters could not find water, which is why his army was heading the wrong way. Beginning to dehydrate, they were beating a hasty retreat through tall mountains and narrow passes to the plentiful wells and supplies of Corinth in an attempt to survive.

Since the Christians had rebelled, they had lost the protection of the Sultan and could be killed, enslaved, or dispossessed.

The Christian commanders considered the tactical matter of motivating people to gather and fight, since there was no Greek state to compel them. What motivated them most? Sheer survival, to be sure, but also, like any army of the time, they expected loot. Word went around that an enormous army was coming, and many Christian captains fled and killed their Muslim hostages and slaves before leaving. But Kolokotronis sent out word that this was a special army carrying untold treasure. Having come from the sacking of Yanena, they carried precious ornaments and metals from the court and palaces of Ali Pasha, sacks of coins, and good horses and pack animals. They carried beautifully ornamented rifles, powder horns, swords, cannon, powder and shot, a lot of coffee, chests, embroidered vests, and cloaks.

Commanders and notables of the Peloponnese turned to the village elders, who, in turn, promised the villagers both loot and survival. No longer waiting passively for Ottoman retribution, the whole population became mobilized. Peasants arrived from all over the Peloponnese, organized village-by-village, with women carrying supplies, joined by local shepherds tempted by adventure. Kolokotronis famously indoctrinated a young shepherd by telling him it was right to kill Turks (meaning Muslims). The shepherd went into battle with his staff and reappeared at the end of the day with weapons stripped from the men he had proudly killed.

While some Christians fled, others arrived and converged on a terrace with walls and a natural spring they denied the Ottomans, keeping the refreshment for those who knew where to look. From there, the rebels fired at the army below, moved in with their swords, gathered the loot, and then moved on and started again. The Ottomans were pinned down and blocked by the enemy, by each other, and by the dead men and horses that began to roll down the hills and pile up in heaps.

Two to five thousand Ottomans died on the spot that July day, a high number for this kind of warfare. The remaining Ottomans poured into the scorched plains of Corinth, Nemea, and Argos, to escape and find water, if they were lucky. More often, they died of thirst, starvation, and armed attacks. Over the next weeks, thousands more armed men and women arrived from more villages, enraged that they had missed the battle and chance at booty, only to be told that the surviving Ottomans still had valuables to yield. Women threw boulders over cliffs, while fleeing Ottomans dropped their treasures to slow the Christian pursuit. In this manner Kolokotronis was able to sustain the campaign into the fall, from Corinth to Nafplio.

Of an army of 30,000 Ottomans, about 6,000 made it back to Corinth that fall; Kolokotronis thought that 4,000 made it out of the Peloponnese, of an army of 32,000. Locals recounted stepping over human bones for years. In his accounts, the beleaguered Turkish mercenary Deli Mustafa described a humanitarian horror. Yet he revealed no animus toward the Peloponnesians, only a lament that he was on the losing side. In his memoirs, Kolokotronis offered a brief, deadpan account of the killing of roughly 26,000 men and the capture of 20,000 horses, 30,000 pack animals, 500 camels, cannon, and cannon balls: “Treasures and beautiful weapons,” he noted. He seemed more proud of the wealth he had shared with the fighters than of the battle itself.

His aide Fotakos, on the other hand, was haunted by the battle. As dusk fell that first day, he witnessed the slaughter of the Ottoman sick left behind in mobile hospitals, who covered their eyes to avoid witnessing their own deaths. As Fotakos left the battle site, his horse stepped on the stacked bodies that had rolled off the cliffs and down hills into the road. A mass of wounded shouted out from the darkened ravines. Their voices mingled with those of the slaves who had been collected from the surrounding villages and abandoned, still bound. Both the dying soldiers and the slaves spoke the major languages of the southern Balkans. Fotakos heard the sprawling, multilingual, multiconfessional empire die in the Little Passes:

“Each cried out his pain to his friends, some in Turkish, some in Albanian, some in Romaic [Balkan Greek], and we could only hear their voices afar and deep in the ravine. Oh Hasan, Oh Dervisi, Oh Ahmet. Oh Thanasi, Oh Konstanti, giam Geka, giam Skondra, giam Christian, I’m a woman, I’m a Christian, I’m a slave. [. . .] Our souls were between our teeth, from fear and from sadness and from hunger.”

The success of the Greeks in the Battle of Dervenakia is owed to the villagers who mobilized themselves. It is unimaginable that the battle could have succeeded without this mass element. Yet just as they began to melt into the Peloponnese with their newfound wealth, they soon also melted from the histories and paintings that spoke only of individual heroes and leaders portrayed as the sole agents of the revolution.

But Dervenakia was indeed a mass event, where villages converged in an organized fashion for the same purpose, in a way they had not before. A modern society is a mass society, and Dervenakia, like the Greek Revolution itself, was one exemplar of independent-minded collectivity, a sharp break with the submissive stability of old. Did they fight for something more than loot? Their own survival, to be sure, the defense of the region very likely, and, little-by-little, what they were told was Hellas being born of the revolution itself, all infused with a heightened sense of their Christianity. It would be that Hellas, a Christian and European one. The others would have to die or leave. It was a dynamic that would be repeated in the Balkans until 1922, when Turkey rid itself of its Christians and formed the modern republic. A last act was Yugoslavia in the 1990s, the attempt to eliminate some of the last Muslims of the region.

Leaving theparking lotand surrounding area for the highway, I stopped for a bite to eat at a place still called Anesti’s Chani. The name contains an Ottoman legacy if ever there was one: a chani is a Turko-Greek word derived from the Turko-Persian hani, a no-frills lodge where people and horses could be watered and fed as they fought off the fleas. One of the bases used by the Christian rebels in 1822, it is now a tavern.

On this day, young foreign couples stopped on their way to and from ancient Mycenae in search of the ruins, oblivious to the more modern history, and they added to the polyphony that has always been the Peloponnese. The owner raced about on his cell phone, preparing for the upcoming May Day holiday. He stopped to chat with me a bit, near an cold natural spring, one of those the Christians had hidden from Ottoman attackers two centuries ago, and where now water flowed around an enormous plane tree that gave us shade.

“Here,” he said. “You can drink from it.”

Image: Vryzakis Theodoros, The Defense of the Homeland above All Else (1858), oil on canvas, 183 × 132 cm. Copyright and courtesy National Gallery of Greece, Alexandros Soutsos Museum. Inventory number Π.643. Photo: Stavros Psiroukis