Artist Portfolio: Lucy Raven

A brief introduction for the unfamiliar viewer

by Pavel Pyś

Reflecting on the problem of documentation, sculptor Carol Bove wrote, in a 2001 Art Journal article: “The official photo takes one moment from [the artwork’s] life and confers on it a special status.” The claim to know an artwork through its photographic reproduction is a dubious one, as all those essential properties—size, scale, texture, color, smell, temperature, and duration—evade the frozen, singular image. In the case of moving-image artists like Lucy Raven, the problem centers on the film still, an elevated, illustrative excerpt deemed to offer maximal insight. I will try to avoid falling into this pesky trap by considering instead some images taken by Raven that, for now, claim the role of “preparatory materials” for AO—a work in progress—to consider broader themes underscoring her practice.

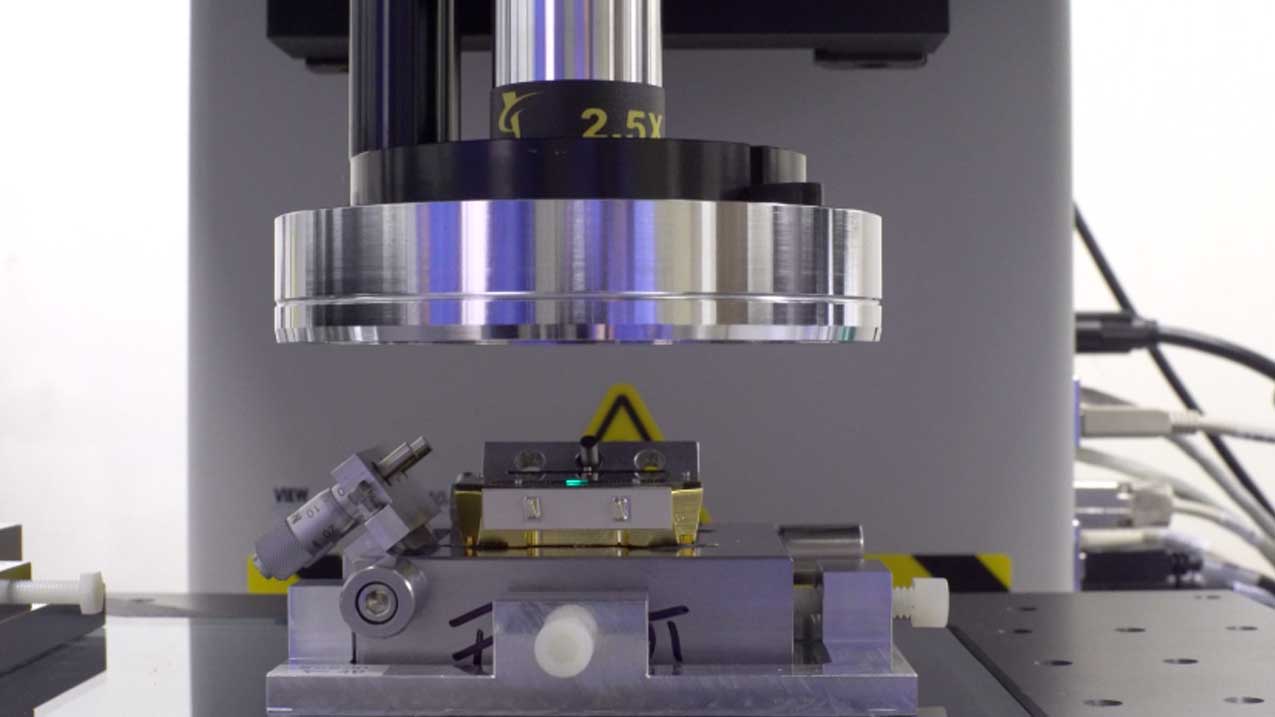

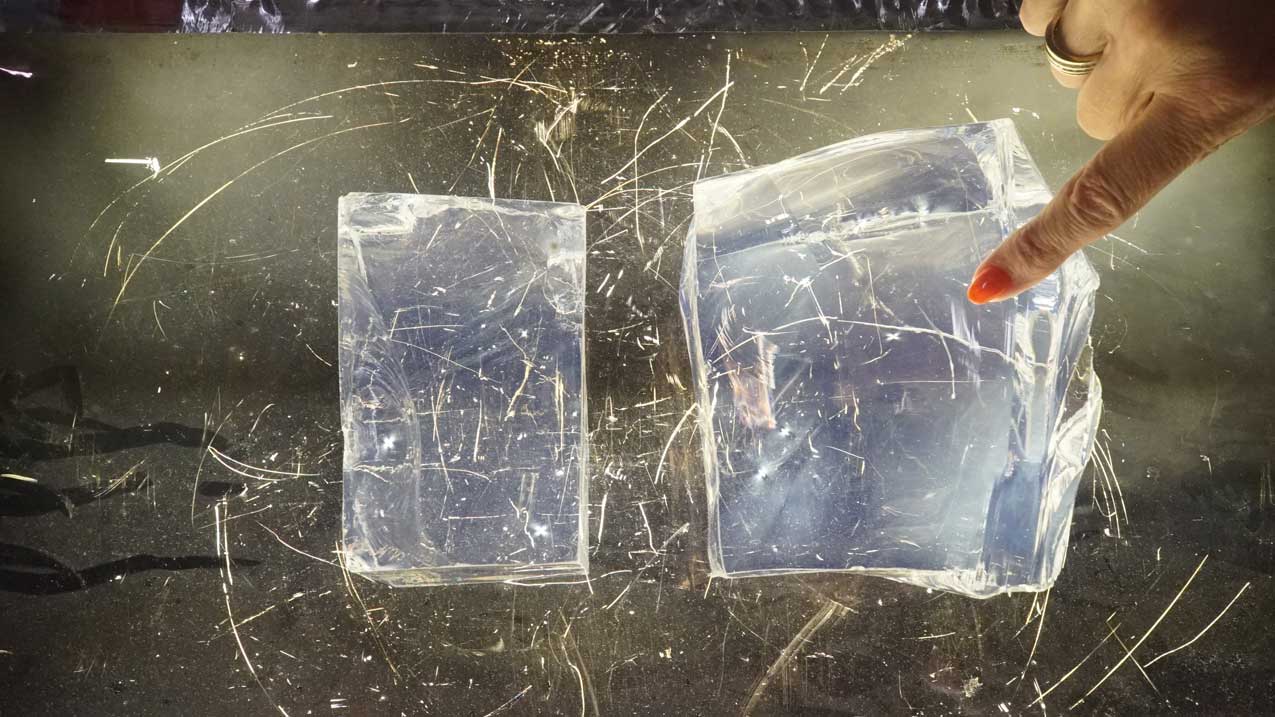

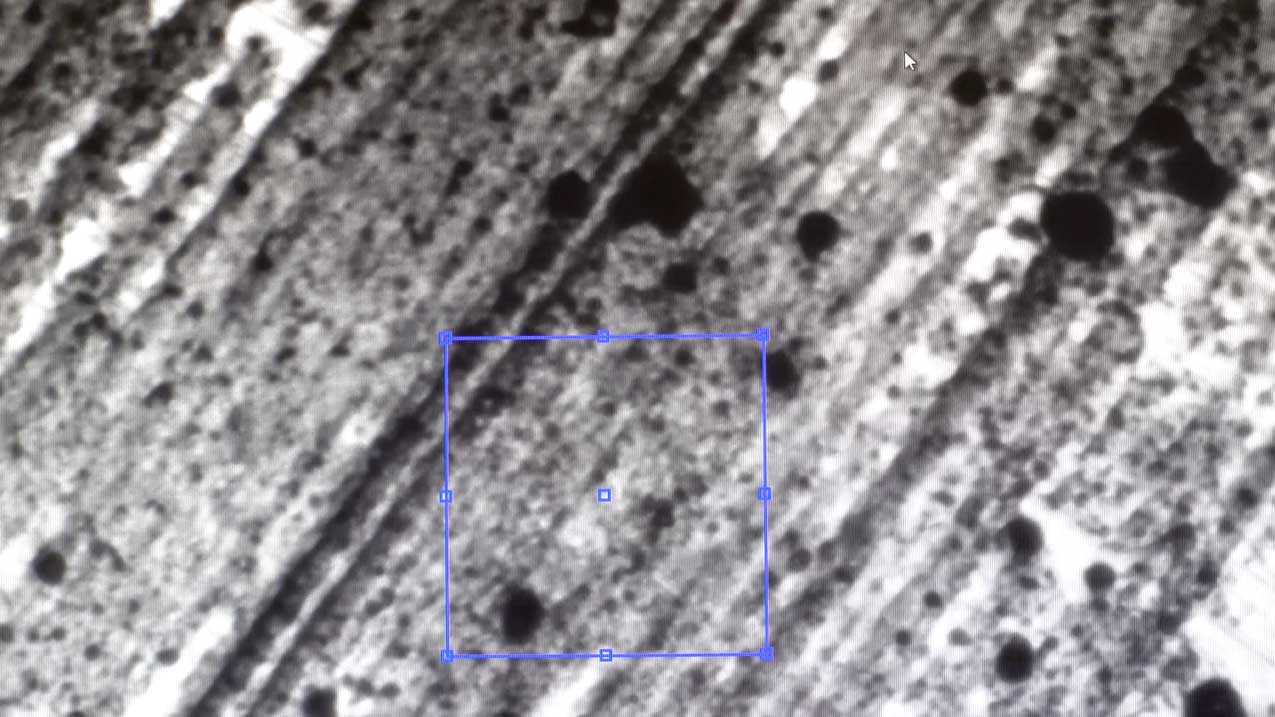

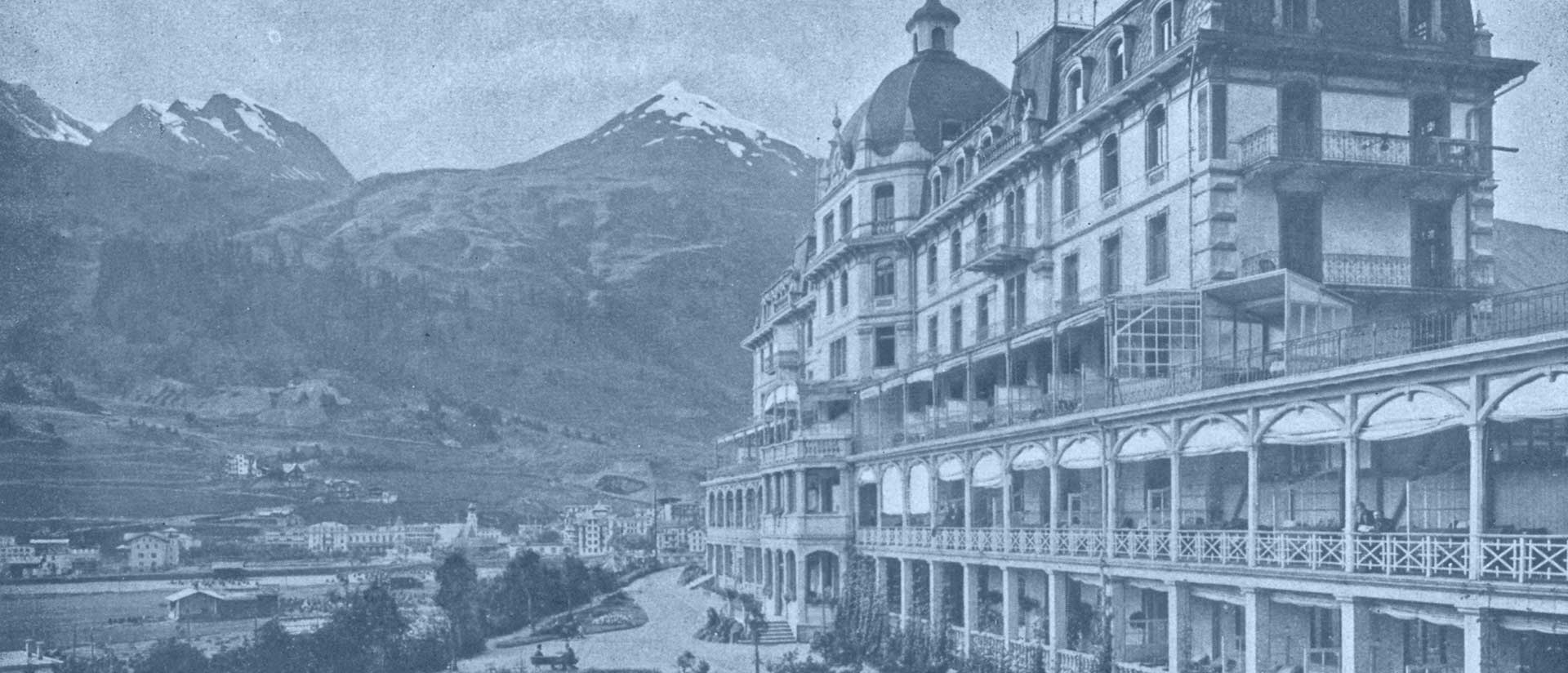

The images reproduced here are either microscopic or simply casual in nature. While they show what appears to be a high-end industrial complex, there are suggestions of the everyday: a bright-red painted fingernail points to shards of glass or lumps of gel, while elsewhere workers are seen in the background chatting and smiling. These originate from the Steward Observatory Mirror Lab, located underneath a football stadium in Tucson, Arizona (incidentally, the artist’s city of birth). Sterile and technical, as well as candid and informal, Raven’s images show the production of state-of-the-art 27-foot parabolic mirrors manufactured for the world’s largest telescopes. The painstaking production process bridges handmade and industrial techniques to yield sophisticated mirrors that allow scientists to capture the most detailed images of our universe.

Throughout her research-driven practice, Raven has repeatedly turned her attention towards the relationships between architectural sites, industrial production processes, and places of labor. Her works address the often-invisible networks or exchanges that facilitate services and products, revealing transnational trade agreements and contemporary global connectedness (though designed in California, do you realize, dear reader, what has gone into the making of your iPhone in China?). Raven’s photographic animation China Town (2009), for example, traces the journey of raw copper ore from a pit mine in Nevada to a Chinese smelter, where it is turned into copper wire, a material used widely as a conductor in the electrification of buildings and telecommunications networks. In The Deccan Trap (2015), Raven forges a relationship between imagery of Indian technicians converting outsourced Hollywood films from 2D to 3D in an office in Chennai, and the carved stone reliefs of the Ellora Caves, a temple complex in Maharashtra. Described by the artist as a “sci-fi fable,” the video work compares how labor—the shaping of forms out of solid, stone material in a real place, and the molding of pixelated immateriality in virtual space—tricks the eye in the creation of a perspectival illusion of depth.

Why might Raven be so attracted to the Steward Observatory Mirror Lab? Drawing on the history of cinema and animation, her work is rooted in questions of how images are crafted, manipulated, produced, and consumed. Take RP31 (2012), for example, a stroboscopic montage of 31 Hollywood test patterns—called “recommended practices” by the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers—typically seen solely by a movie-theater technician to adjust focus, aperture, and framing for optimal viewing. With each frame corresponding to one test pattern, Raven points to this typically unseen directive, while also prohibiting its full contemplation due to the work’s rapid succession of imagery. In RP31, The Deccan Trap, as well as other works, Raven turns to acts of looking and seeing to explore the limits of perceptibility and the ways in which technology aids or tricks the human eye.

When considering Raven’s interest in telescopic mirrors in Arizona, I am reminded of the painter Vija Celmins, whose work sources images of stars and galaxies. “I’ve always liked the scientific image,” she said, in a recent Tate film about her work, “because it’s sort of anonymous, and often the artist for the image has been a machine […] I like the idea that I can relive that image and put it in human context.” Raven, much like Celmins, is interested in how the mechanical affects the personal, determining the nature and boundaries of experience.

(All images are stills from Raven’s 2018 project AO)

Pavel S. Pyś is Curator of Visual Arts at the Walker Art Center, in Minneapolis, Minnesota.