Aren’t They Strange

The exemplary deaths of premodern Chinese individuals

by Ying Zhang

Two common attitudes arise when we read about peoples and cultures that seem alien or strange: we adopt either a linear view of human progress—“That was a terrible world. We are in a much better place now”—or we adopt a kind of moral relativism—“That’s certainly a very different way of life. But we should not judge it.” Both these attitudes, by reinforcing the divide be- tween the familiar and the unfamiliar, prevent us from con- fronting difficult questions in meaningful ways. Studying some of the most characteristic phenomena in premodern Chinese history—for example, extreme behaviors motivated by strong Confucian ethical convictions—has led me to think about how to help us go beyond these two attitudes.

We can learn, for example, from the experiences of Western-educated intellectuals in modern China who viewed “traditional China” as being as strange as it is to us today. I encountered two such intellectuals in my research on imprisonment, spirituality, and politics: Zhang Dongsun (1886–1973) and Su Xuelin (1897–1999). Zhang refused to ex- plain his suicide attempt as a conventional act of political loyalty, and instead confessed his vulnerability as a human being. Su acknowledged the critical thinking capabilities of premodern exemplars and recognized a universal quality in their spiritual pursuits. The ways in which their actions and writings engaged the past defy simple generalization. Once we disentangle them from modern discourses of national- ism and gender, they become more relatable to us.

Immediately after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the breakout of the Pacific War, in December 1941, some faculty members of the Yenching University, an institution with deep connections with the United States, became war prisoners in Japanese-occupied Beijing. Among them was the renowned philosophy professor Zhang Dongsun. While in prison, Zhang attempted suicide multiple times. The first method he tried was hanging. According to his own account, he felt so thrilled about the idea of suicide that his heart raced, and his hands were sweating. He blamed the failure of this first attempt on his excitement: had he been able to control himself and waited longer, till midnight, the noise made by his struggling body would not have alerted the guard. Zhang then tried to starve himself to death, but then changed his mind because it would have taken him a long time to die. He hit him- self with the handcuffs. But al- ready physically weak, Zhang could not hit his head force- fully enough. Again, the noise alerted the guard.

Next, Zhang yelled at the guards, hoping that they would be provoked to give him a quick execution. The Japanese saw through him and left him alone. Zhang then tried to stuff his nostrils to suffocate himself. But this experiment failed miserably. After all these unsuccessful attempts, he became more obsessed with his suicide mission. One day, he saw a nail on the wall, “a really big one!” The excitement struck again. He pointed his head at the nail and ran toward it. Only then did he realize that “the human skull is the toughest thing in the world.” The nail did not immediately kill Zhang but instead caused severe bleeding. He tried to make himself bleed more. “The more the blood on the floor, the happier I was!” is how he described his state of ecstasy.

As scholars in the discipline of prison studies have shown, experiences of confinement vary significantly for individuals, ranging from depression to bliss. These very human reactions require us to resist simple generalization and to instead vigorously contextualize suffering and agency. Zhang himself confessed that the psychological pain caused by solitary confinement, threat of torture, and physical illness pushed him to the limits. Although he felt that a successful suicide might upset the Japanese because it “could be seen as a sort of resistance,” his primary goal was to end the unbearable physical and mental suffering.

As scholars in the discipline of prison studies have shown, experiences of confinement vary significantly for individuals, ranging from depression to bliss. These very human reactions require us to resist simple generalization and to instead vigorously contextualize suffering and agency.

Zhang described how the confinement had driven him to commit suicide to the theologist Zhao Zichen (1888– 1979), a colleague also imprisoned by the Japanese. Zhao believed that Zhang was experiencing a spiritual crisis. In his eyes, Zhang’s “restlessness” confirmed the necessity of the Christian faith. When they began to share the same cell, Zhao spent some time explaining to Zhang the sacrifice of Jesus Christ and the importance of preserving their lives as a patriotic act. This documentation directly contradicts the popular interpretation of Zhang’s suicide attempt. The Chinese public, including scholars today, have insisted on reading Zhang Dongsun’s suicide attempt as motivated by anti-Japanese patriotism.

The first reaction I had when coming across Zhang’s account of his suicide attempt in prison was quite different. I had just read a very similar suicide story in a book published around the same time of Zhang’s arrest, about a chaste wife in the mid-seventeenth century. I found the similarities between these two suicide stories striking, but I also found it fascinating that they triggered different public reactions.

In 1646, during the Manchu conquest of China, a woman surnamed Zhou learned that her literatus husband had been imprisoned by the invaders. She decided to commit suicide and tried a few methods. First, Zhou attempted to hang herself, but she did not die. Drowning failed as well. She then tried the ancient method of swallowing gold. It did not kill her. A friend of her husband’s thought the gold she had swallowed was not pure enough. So he ground his wife’s rings to obtain purer gold for Zhou. The purer gold, however, did not produce the ideal result. Next, Zhou slashed her own throat, but somehow she came back to life. Desperate and determined, she hanged herself once more. This time, it worked.

Stories of loyal men and chaste women who used suicide as a means of self-expression fill the pages of Chinese imperial histories. They were commemorated as Confucian moral exemplars, earning mentions in local gazetteers and dynastic records. The story of Zhou’s suicide would not have been so problematic if it stayed as the past. But it appeared in 1941 in a book published in the wartime capital of the Republic of China during WWII. The Biographies of Loyal and Brave People in the Southern Ming presented individuals who died heroically during the violent transition from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) to the Qing dynasty (1644– 1911). Commissioned by the Propaganda Department of the nationalist government, the Catholic scholar Su Xuelin compiled it for the war mobilization effort. The first edition of this book, which I examined at the Harvard-Yenching Library collection, carries distinct marks of war-time hard- ships: coarse paper, poor printing, fragile binding.

Stories of loyal men and chaste women who used suicide as a means of self-expression fill the pages of Chinese imperial histories. They were commemorated as Confucian moral exemplars, earning mentions in local gazetteers and dynastic records.

Artistic and scholarly representations of the historical “heroes” exploded during the anti-Japanese war. The public generally accepted the war propaganda that promoted patriotism by invoking loyalty to the imperial dynasties threatened by foreign invasions. Su Xuelin’s book fell in this category of publications. But it met with harsh criticism from some prominent male scholars at the time, who judged her book with conventional historiographical expectations. When I read the book as a typical seventeenth-century specialist, I would agree with such criticisms. But Su’s decision to include records of chaste women in this book intrigued me, and it further convinced me that her intellectual and moral explorations deserved serious consideration.

Su’s editorial choice was so extraordinary because, in the Republic of China, female chastity was denounced as a symbol of Confucian oppression. Whereas Zhang Dongsun’s suicide attempt could be readily (mis)interpretated as an act of patriotism, Su’s representation of the woman Zhou’s suicide did not fit well in the modern discourses of nationalism and women’s liberation. Comparing the two suicide stories and the public reactions to them, I could not help but ask: Does this really confirm Su’s inability to break away from her traditional gender upbringing, as scholars of modern literature often lament? Are there other ways to understand why she refused to treat the Confucian exemplary men and women differentially?

In the young Chinese republic, Su had enthusiastically embraced the New Culture movement that condemned the Confucian tradition that dominated the imperial past. She became one of the first modern Chinese female writers. While in high school, she composed biographies of several chaste women in her hometown and an essay documenting a classmate’s cutting her own flesh to save her mother’s life, a common way of expressing one’s Confucian filial piety. In the 1920s, after returning from France, she published sever- al articles on two important topics: patriarchy and relativism. Recalling how her mother fulfilled her feminine roles gracefully despite the mother-in-law’s abuse, Su pointed out that men and women of the old times were victims of the dominant Confucian ethics, from which they had nowhere to escape. She argued that “each generation has its own moral standards” and one should not measure the previous generation by the new standards.

Witnessing endless human suffering, especially during the war, however, seemed to have changed how Su Xuelin related to historical figures’ choices and actions. She began to actively seek ways to solve the contradictions among her different beliefs, especially in terms of reconciling her Catholic faith and her other interests such as Confucianism, science, and literature. She proposed that the older generations’ practice of Confucian virtues such as loyalty and filial piety did not necessarily mean they blindly followed oppressive norms. What really mattered was “sincerity” in their selflessness, Su argued in her commentaries on prominent contemporary figures who, like premodern moral exemplars, cut their own flesh to make medicine for a parent. The recognition of and emphasis on sincerity, a spiritual quality pursued universally in human history, allowed Su to empathize with premodern Confucian moral exemplars despite her strong opposition to patriarchy. This empathy helped connect her varied self-identities, Chinese, Catholic, and modern. This also explains her decision to include a woman’s sensational suicide, together with many other stories of seventeenth-century loyal, filial, and chaste subjects, in a modern war-mobilization book. Su hoped these stories would inspire individuals to take courageous actions motivated by sincere self-sacrifice.

The older generations’ practice of Confucian virtues such as loyalty and filial piety did not necessarily mean they blindly followed oppressive norms. What really mattered was “sincerity” in their selflessness, Su argued in her commentaries on prominent contemporary figures who, like premodern moral exemplars, cut their own flesh to make medicine for a parent.

By situating Su Xuelin’s personal exploration in the longer history of Confucianism and Chinese religion, her scholarly and literary choices become more intelligible. At the risk of being blamed for endorsing female chastity, she wanted to reflect on a historical woman’s agency and spirituality. Su’s transformation illustrates something not only central to Confucian classical studies but also universal: the process of learning to understand Others is a process of self-discovery and self- cultivation. Many Confucianists in premodern China underwent a similar process. They did not simply memorize the classics for examinations. In their everyday life and work, they reflected critically on the philosophical and social theories passed on from the olden times, including biographies of moral exemplars and their extreme behaviors. Many Confucian scholars theorized tirelessly on the concept of sincerity in their practice of Confucian ethics and rituals, even if they did not take extreme actions in their own lives.

A similar pattern of empathetic emulation and critical reflection is apparent in the history of imprisoned elite men in imperial China. A handful of them were firmly established as exemplary prisoners, thanks to the efforts made by many generations of Confucian-educated men who, in poetry and art, commemorated the suffering and injustice that these men had to endure. Ordinary folks installed these Confucian exemplars as cult deities out of the belief that their extraordinary moral convictions (which sometimes resulted in a heroic death) could generate magical protective power. Maritime merchants and migrants took these worshipping practices with them on long journeys and to new homelands. What motivat- ed both the elite and ordinary folks was a sincere appreciation of—not dogmatic imitation of—the sincere selflessness demonstrated by those historical figures in particular situations. This historical phenomenon cannot be reduced to ideological brainwashing.

In the end, these Chinese historical subjects— premodern elite prisoners and their worshippers, Western-educated modern intellectuals and their personal struggles—present to us the complexity of humanness that needs deep contextualization to be fully grasped. Emotional vulnerability and spiritual conviction could both lead to the extreme action of suicide. The Confucian exemplarity could be invoked to serve drastically different spiritual needs. It takes open-mindedness and willingness to suspend our analytical habits and communicate with them. But the reward is priceless: humanizing strangers from a different time and space and making their lives and choices comprehensible to our contemporary selves.

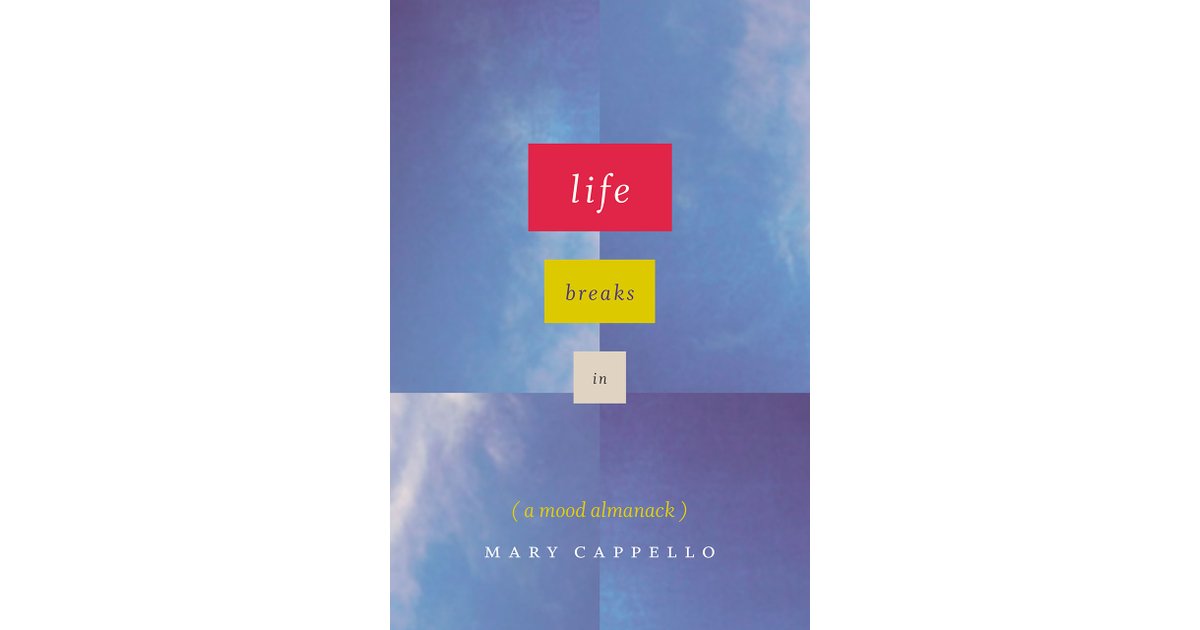

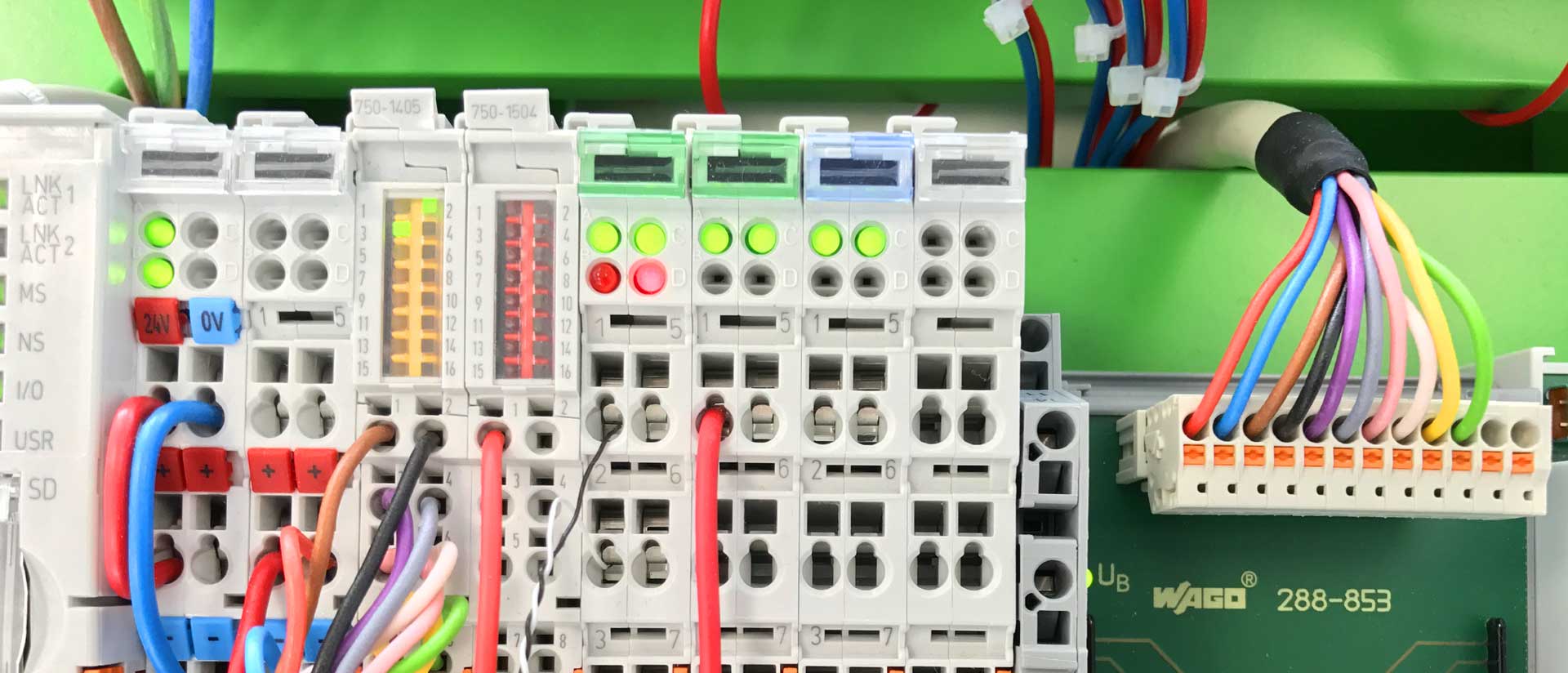

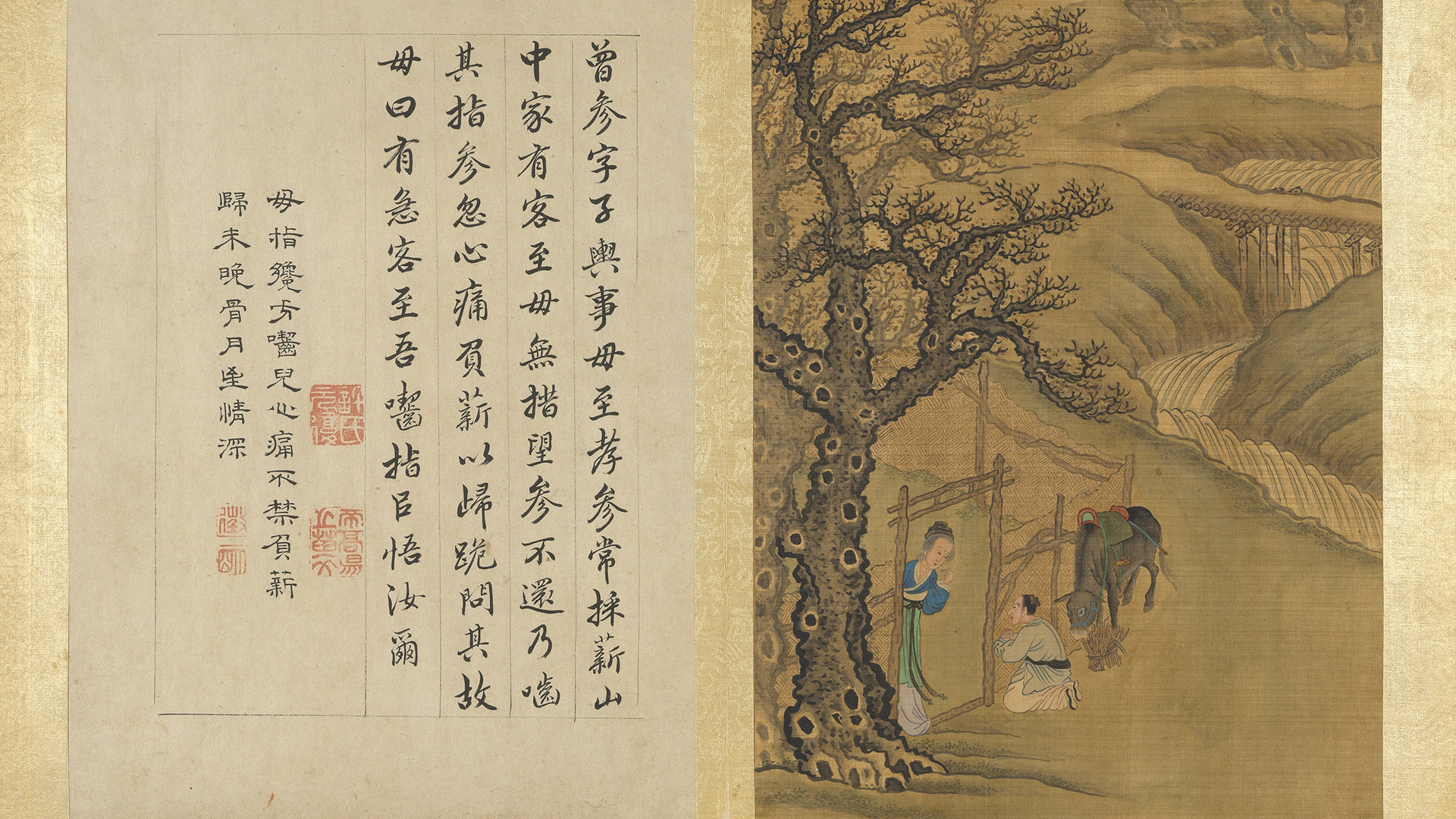

Image attributed to Qiu Ying (d. 1552), Pure Filial Piety, Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), ink on paper, painting album. National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. Calligraphy by Zeng Shen (505–435 BC): “Went to the mountains to gather firewood. One day some guests came to visit. Zeng’s mother did not know what to do. Waiting for her son anxiously, she bit her finger. Zeng felt a sharp pain in his heart. He rushed home with the wood he had gathered.”