God’s Law

Islam and politics in the United States

by Mark Fathi Massoud and Kathleen M. Moore

We met Kareem at a local Denny’s restaurant just off the freeway in southern California. A progressive Black community organizer in his late forties who runs a nonprofit organization, Kareem told us that he converted to Islam as a young man, calling it his acceptance of “God’s will over man’s will.”

Kareem grew up Protestant in a rough, gang-ridden neighborhood of Los Angeles. As a child, he equated the law with the cops or, more accurately, “grown-ass men wearing badges who’d put you in the back of their car.” On the street, Kareem learned to stay away from the law: “Eight times out of ten, you did get your ass whooped if you wasn’t fast.”

Kareem paused and took a sip from his mug. And then he said this: “The US Constitution is a great document.” We invited him to explain. He replied that the Constitution was similar to sharia, commonly translated as Islamic law. Both sharia and the Constitution create space for “ diversity, human rights [and] the freedom to think.”

Kareem is not alone. In our research over the past decade with Muslims across California—a place with more Muslims than nearly any other US state—we met many people connecting religious values and American law. They did this to protect rights, not to curtail them.

A great battle exists in American politics between people on the one side who connect religion and rightwing ideologies in order to deny rights to women, minorities, and queer persons, and people on the other side who argue that, in order to protect civil rights, religion must be kept out of politics.

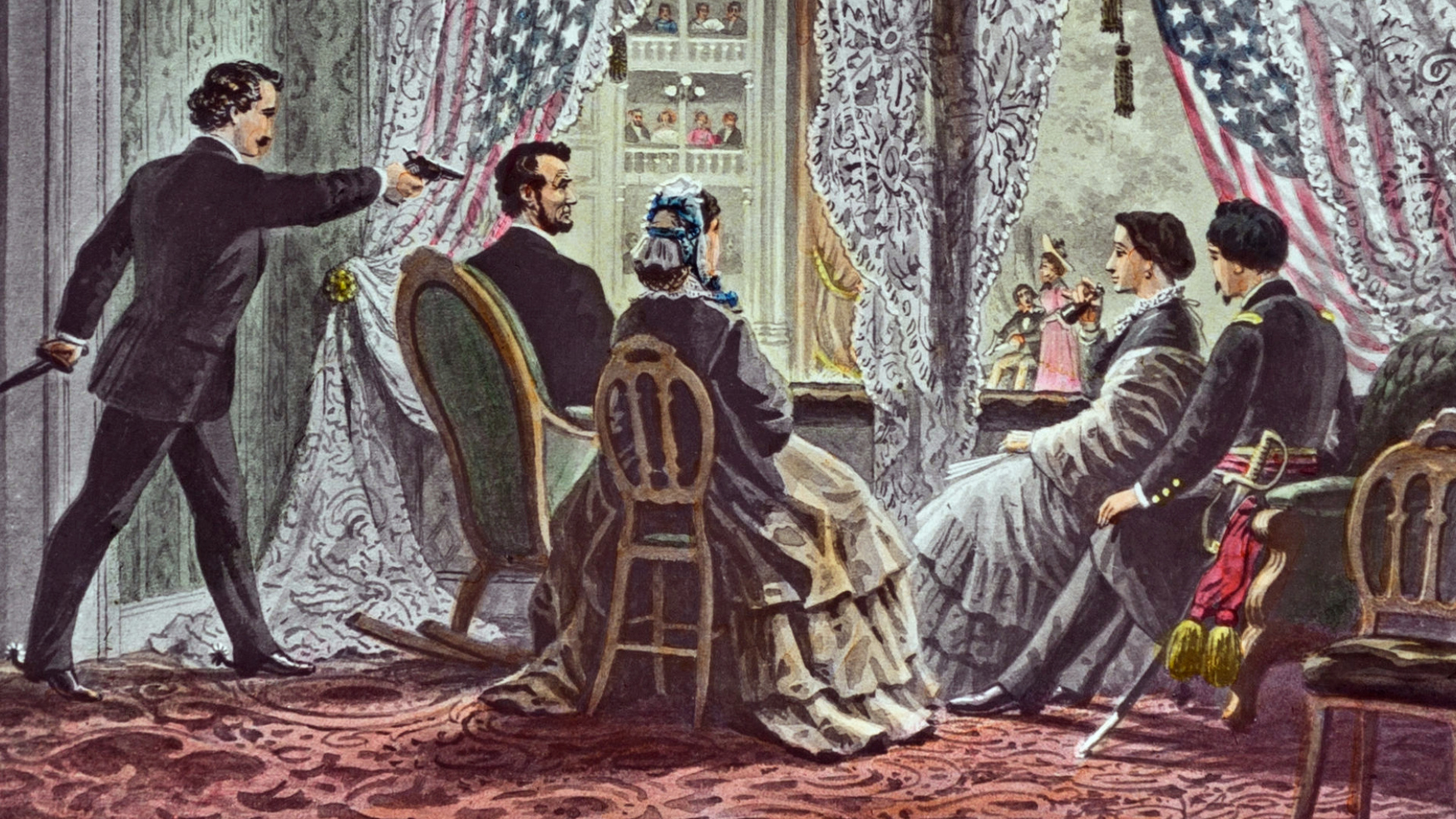

The eighteenth-century founders, Protestant Christians all, imagined a religiously free United States, but they were ignorant of the fact that some of the slaves they counted as property were Muslims. Nineteenth-century American judges regularly invoked the maxim that Christianity “is part and parcel of our common law” to justify the nation’s westward expansion and the associated slaughter of Native American communities. On January 6, 2021, people carried bibles, crosses, and flags that said “Jesus 2020” and “Jesus Saves” as they stormed the US Congress to stop the certification of President Joe Biden’s election.

According to a Gallup poll, public confidence in the US Supreme Court reached a historic low after the Court’s 2022 decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, which since 1973 had protected a woman’s constitutional right to access abortion. Conservative religious groups had been calling for this action for decades, and more Americans began to see the justices of the Supreme Court as political or religious partisans.

The American Civil Liberties Union, a progressive litigation and lobby group, has responded to this legal politics of religion by asserting that “There’s no good reason to abandon the separation of church and state, and every reason to ensure that it remains strong.” On the Supreme Court, the reign of the strict separation of religion and state came to an end with the accommodation of religious conservatives. The progressive refrain reasserts the independence of religion and its separation from the state, both enshrined by the First Amendment.

Not every person in the US believes that either religion should stay out of politics or, if religion enters politics, it ought to align with right-wing values. A third group exists. This group includes people like Kareem who turn toward, rather than away from, religious faith in their struggles against injustice, poverty, and oppression. Their understanding of civil and political rights comes in and through their experience of God through sharia. For many Muslims we met, sharia enabled humility when they sought to follow God’s will. This submission to God became their guide to ethical living and a source of democratic values like freedom.

For many Muslims we met, sharia enabled humility when they sought to follow God’s will. This submission to God became their guide to ethical living and a source of democratic values like freedom.

What is sharia? In practice and politics, sharia is a contested concept that means different things to different people. It is an Arabic word that generally refers to “the way” or “the path to water.” Muslim jurists have drawn on primary sources—the Quran (Islam’s holy book) and the Hadith (the words, actions, and tacit approvals of the Prophet Mohammed) to formulate rules based on their interpretations of these sacred texts.

However, for many Muslims in the US who are living out their faith as religious minorities, translating sharia as “Islamic law” is not entirely accurate. Broadly understood, sharia is much more than jurists’ rulings. It is “the path” to God that provides ethical principles shaping everyday living, such as honoring one’s parents or feeding the poor.

Like people of all religious traditions, Muslims do not always follow the dictates of religious leaders. Instead, some of them create their own interpretations of sharia, even when they are not conscious of doing so. Sharia has thus offered a different discourse, taking on a multitude of context-sensitive meanings related to daily life, religious practice, and politics.

Consider Nargis, a young Californian filmmaker of South Asian heritage. In our interview with her, she admitted, with a nervous laugh, that sometimes she felt challenged by the “progressive” character of sharia. Islam made her “a lot more liberal than” she wanted to be, she told us. Influenced by sharia’s demands for justice and equality, she voted against California’s Proposition 8, back in 2008. This was a ballot initiative that would have banned same-sex marriage. “I would have voted” against gay marriage, she said, “but then, after I looked more into sharia, I realized that no, Islamically [voting against Proposition 8] is the right thing to do . . . [e]ven though . . . I was doing something too liberal . . . for me.”

We met Muslims who fasted for Ramadan and those who did not. We met Muslims who had engaged in premarital sex, and those who waited until they were married. We met Muslims who had eaten pork and drank alcohol, and others who abstained from both. Tariq, a middle-aged man, told us that he “grew up working class . . . If you didn’t drink, you were weird. And so, I drank.” Recognizing that sharia gave him the “freedom to disobey the law,” he has also come to seek God’s guidance in the “smaller, day-to-day kinds of things.” He does not drink in excess. He prays regularly. He also attends jumu’a, the Friday congregational worship.

Kareem, Nargis, and Tariq each used sharia as a source for their freedom to choose how to live out their most ethical lives. However, a public perception has emerged that sharia is an unyielding religious law whose tenets are potentially threatening. This perception that Muslims must blindly obey a harsh interpretation of sharia “racializes” Muslims as inferior and suspicious others by fusing cultural attributes to religious identity and rendering them markers of radicalism. These markers are also gendered—for instance, men with long facial hair being seen as dangerous or women in hijabs as powerless or unreformed. A specific understanding of American law and of sharia as inflexible and incompatible systems is key to producing this racialization.

This perception that Muslims must blindly obey a harsh interpretation of sharia “racializes” Muslims as inferior and suspicious others by fusing cultural attributes to religious identity and rendering them markers of radicalism.

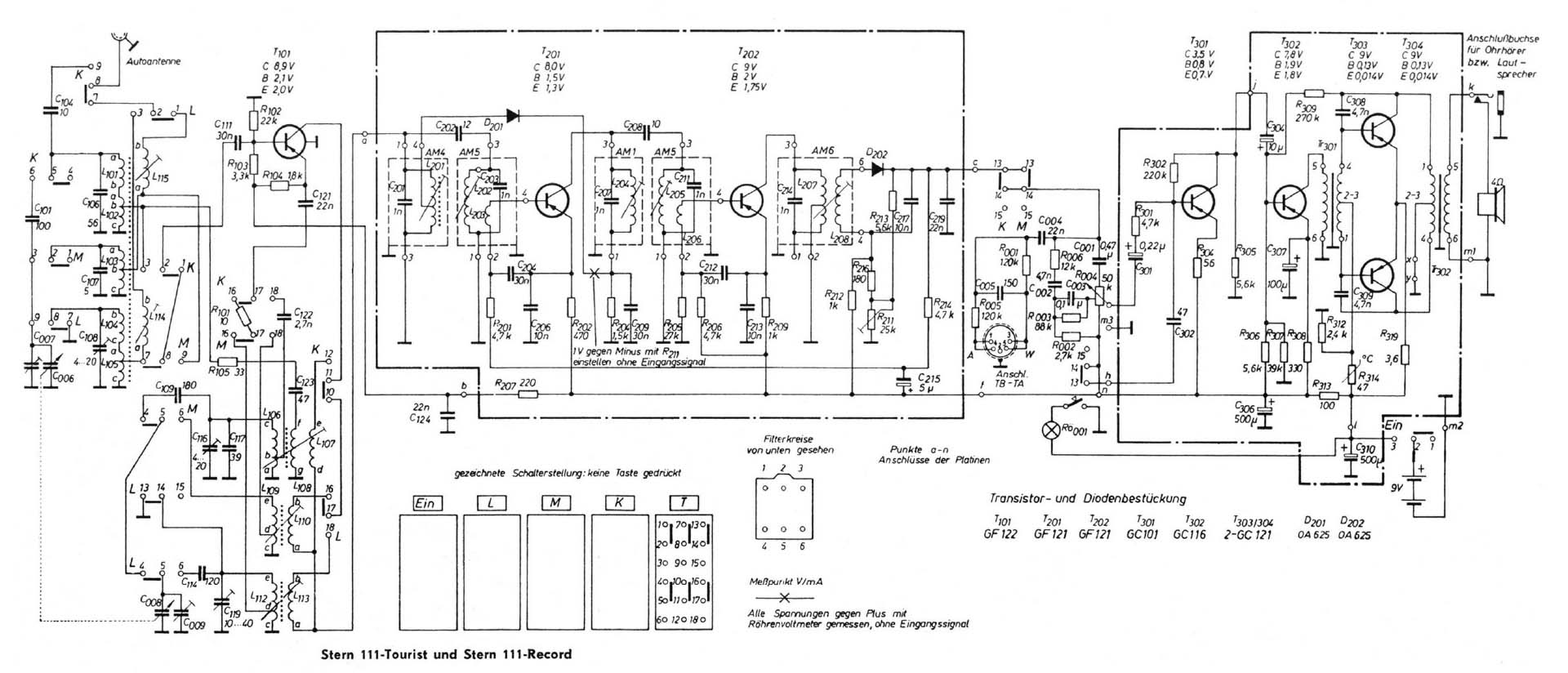

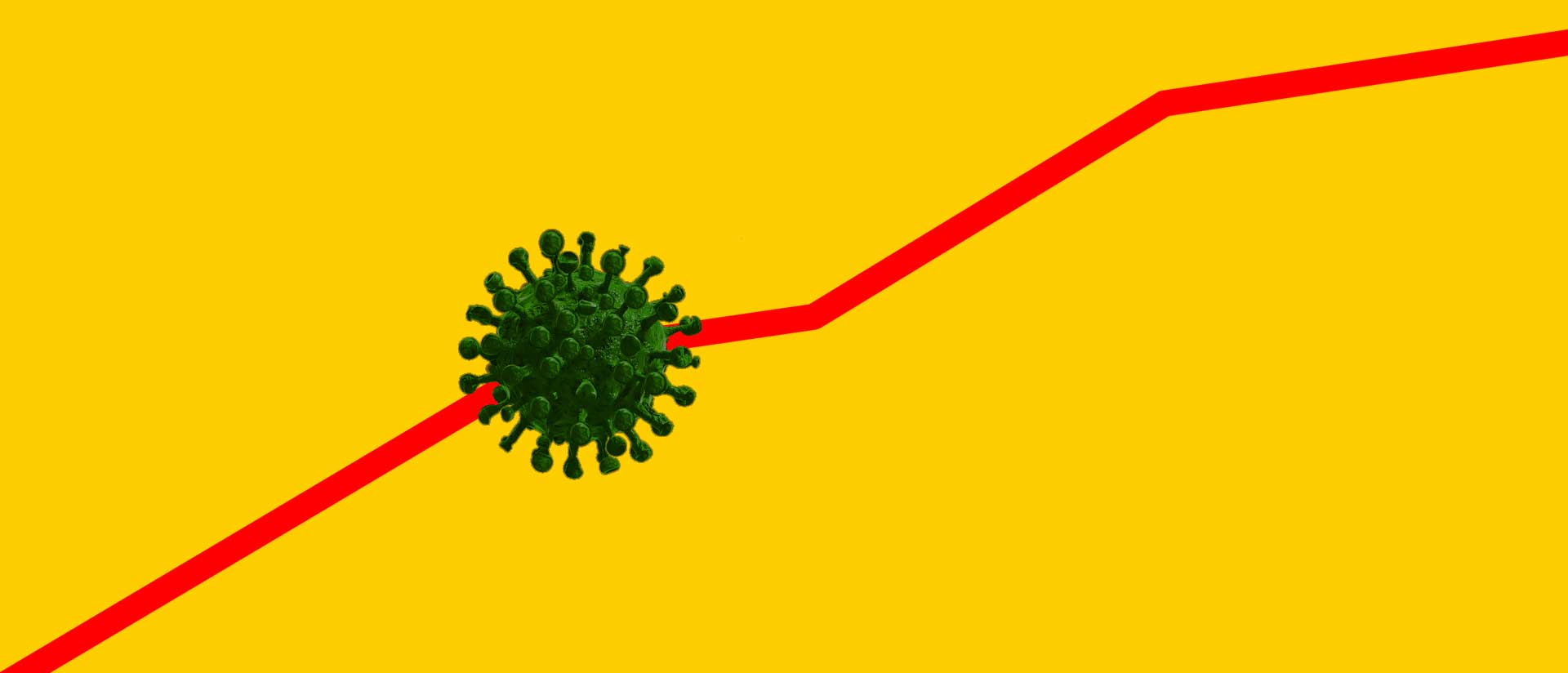

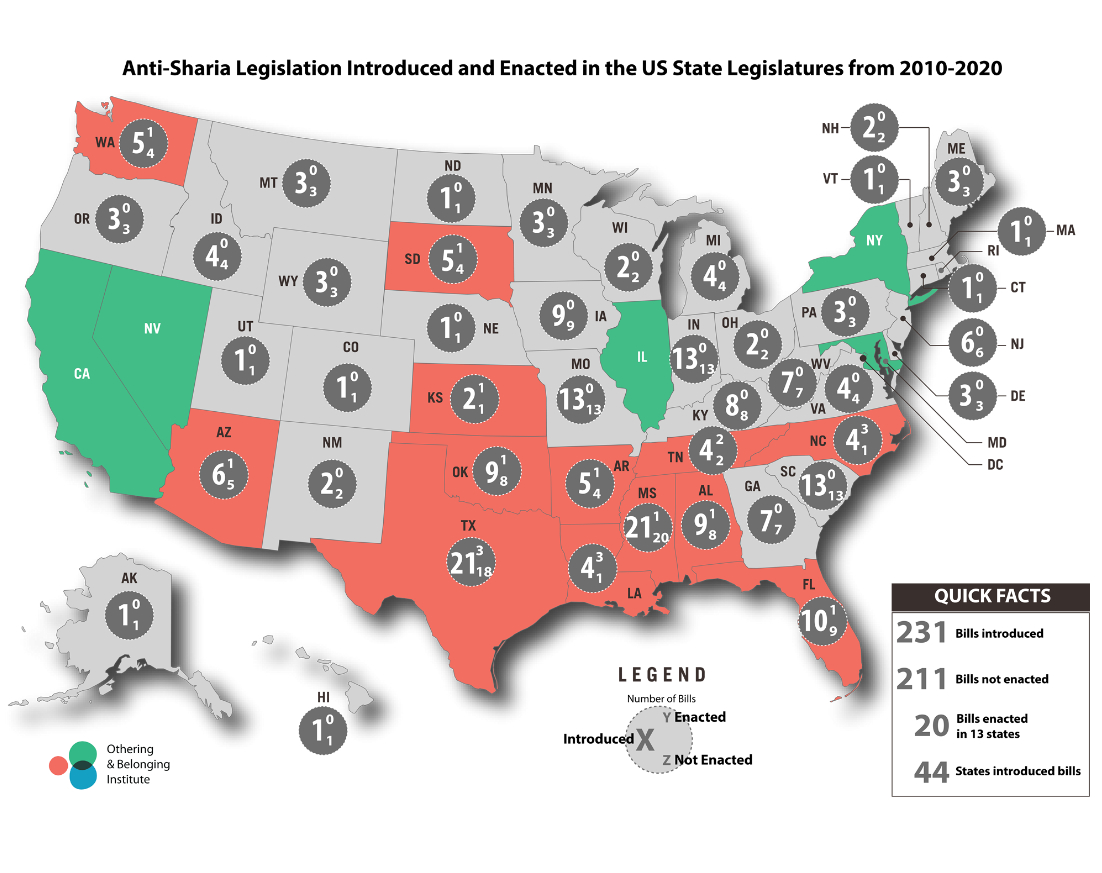

The result of this racialization has been a public outcry over sharia—in part out of fears of extremism, terrorism, and corporal punishments. This has led US Senators to label sharia “evil,” and conservative analysts to call sharia the world’s “other pandemic,” in a comparison to Covid-19. Most state legislatures have introduced bills to ban sharia, more than 200 of them since 2010 (see figure below). In 2017, the US Supreme Court partially upheld an executive order denying visas to citizens from seven Muslim-majority countries, giving legal weight to the popular characterization of Muslims as a threat to American security.

Anti-Sharia Bills Introduced in the US, 2010–20 Source: UC Berkeley Othering and Belonging Institute

The depths of racism and inequality in the US—and the depths of contemporary anti-Muslim hate—cannot be understood without attention to religion and, specifically, to the long history of exclusion of religious minorities. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, an intellectual enlightenment took hold of Europe. It was an “age of reason” in which philosophers, jurists, economists, and scientists fundamentally rethought human nature. They connected humanity to higher ideals of rationalism and freedom of thought, a rupture from centuries of political thought drawing from and bounded by religious faith. Organized religion, these intellectuals contended, had been the source of too much political power and too many devastating wars.

The Enlightenment fueled anti-Catholic and anti-Muslim sentiment in northern Europe. This hostility made its way into colonial North America, infusing the founding of the United States. According to the historian Denise A. Spellberg, the founders saw both of these religions as sources of tyranny “antithetical to American ideas of liberty.” For decades after America’s founding on those philosophical principles of liberty, Catholics were systematically denied the right to hold political office, and Muslims were presumed not to exist outside of exotic, faraway lands.

For decades after America’s founding on those philosophical principles of liberty, Catholics were systematically denied the right to hold political office, and Muslims were presumed not to exist outside of exotic, faraway lands.

In the 1850s, as the US was headed toward a civil war, a growing xenophobic or “nativist” movement took hold of lawmakers and statehouses, coalescing into the national Native American Party. Its membership combined anti-Black prejudice with growing Protestant resentments against working-class Catholics, who for a generation had been immigrating to the US from Ireland and Germany.

In Philadelphia, the city where the US Constitution had been written and signed in the 1780s, nativists rioted in 1844 to stop Catholics from voting and from reading their version of the Bible—instead of the King James version that Protestants preferred—in public schools. Anti-Catholic militants also bombed churches and attacked priests, including by tarring and feathering them.

In the twentieth century, American anti-religious extremism found another target. Discriminated against as minorities in Europe, Jewish immigrants to the US faced more barriers to acceptance. To avoid confrontation, some took new names. The social theorist Robert Merton, for instance, was born Meyer Schkolnick; he anglicized his name in the early twentieth century during a time when Jewish immigrants faced systematic exclusion from American universities, businesses, resorts, and other social institutions.

Since the late twentieth century, a religious enemy has cohered in Islam, specifically in the notion that Muslims in America, especially those who immigrate from the Arabic-speaking areas of the Middle East, pose a threat to US national security.

Shortly after taking office in 1969, President Richard Nixon directed the FBI to add Arabs to its counterintelligence program, COINTEL PRO , which had already been surveilling Black American civil-rights activists.

Continued FBI sweeps of Arab communities expanded into Nixon’s 1972 “Operation Boulder,” in which federal authorities tracked down and interrogated every Arab university student in America, to ascertain their possible links to communism and terrorism, as well as their support for Palestine, sometimes handing this information over to Jewish groups.

Other surveillance programs flourished in the early twenty-first century after the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security. Federal authorities, as well as state and local police, targeted terrorists and potential terrorists. However, in practice, these programs over-reached and under-delivered by targeting Muslims and suspected Muslims.

It is in the context of centuries of American racial and religious exclusion that American Muslims find themselves living today. It is also in this context that Kareem, the man whom we met at Denny’s in southern California, came to understand and turn toward sharia.

“God’s permission,” Kareem said, has allowed him to “get out of a state of apathy and helplessness” to help make his community a better place to live. Kareem’s civic activism has focused on empowering youth in urban areas to better their lives through sports, education, community building and awareness. Sharia has taught him to ask himself, “What can you do for yourself [and] how can you contribute to make things better?”

Sharia has taught him to ask himself, “What can you do for yourself [and] how can you contribute to make things better?”

Kareem’s understanding of sharia has led him even further toward a cosmic or universal understanding of life, which “is bigger than the Earth [and] bigger than you and me,” as he put it. He has begun to understand his out-of-placeness in a nation that has long objected not only to his Blackness but also to his Muslimness. Kareem told us how he has come to understand the importance of freedom— a core American value—when he willingly accepted Islam without coercion. Ending our conversation, Kareem reflected on being American: “I feel good claiming I’m an American,” he said, “because I can contribute to the game and help change it.”

“The greatest thing we’ve got,” Kareem said before we ended our interview, “is to be able to think. The laws of [the United States government] help us to think, and that’s what sharia is. Sharia is the freedom to think.”

This article first appeared in the Berlin Journal 37 (2023-24).