The Miss April Houses

Fiction by Angela Flournoy

After a survey of university trustees, experts, faculty and community members, the Committee puts forth the following recommendations:

In literature associated with the property, prior occupants of the “Miss April Houses” should be referred to as “people” or “inhabitants.” In special circumstances approved by the Committee they may be referred to as “workers.” Under no circumstances should they be referred to in any other fashion.

The committee lacked a librarian, they explained. I was new to campus. So new that my badge wasn’t programed yet. For the first month, I had to stand out front of the Jefferson Building in the humidity before each meeting (twice weekly, at lunch) and wait for another committee member to swipe me in. It was usually Becca Samuels, from campus counseling, with her enamel pins and cat-eye glasses and shaved side, making me feel like I hadn’t moved to a new place at all. Then we’d sit around a conference table in the Office of the General Counsel. My job at these meetings, as it was explained to me, was to vote when called but mostly to listen to the proceedings and at the very end consider how the library might set up a webpage with links to supplemental information and research suggestions for interested students and visitors. That wasn’t the only reason I was there, I suspected, but it was a fancier job than I’d had before, and fancy jobs always have their particular requirements.

Nobody wants to be stuck in meetings during their lunch break after just having moved a thousand miles and not even having time to get a lay of the land, or buy a microwave or figure out where to get decent towels, but I figured it could have been worse. We could have used parliamentary procedure and meetings could have gone on forever. Instead Dr. Gander, the co-chair, kept the meetings under an hour each time, no matter what.

The Committee endorses the Board of Trustees’ proposal to continue calling the structures in question the Miss April Houses and approves the following language for a commemorative placard at the site:

Miss April Lee-June Walters (1902-1974) was born in House #2 and lived in both houses with her two sons and first husband, John Binker Walters (1897?-1955), then with her second husband, Woodrow Gendry II (1920-1981). Miss April was a cherished part of the University community and a longtime member of the hospitality and dining services staff. During the Great Depression vegetables generously shared from her small farming plots were often the sole source of fresh produce that students and faculty ate. Following campus expansion in 1963, when the houses were moved from the southeast to northwest corner of campus, independent community members replanted Miss April’s garden, ensuring that she enjoyed sustainable, locally grown produce for the rest of her life.

It was right around the time that my badge started working that Nnamdi Watson, PhD., joined the committee. A visiting lecturer in African-American history with a five-year appointment, which had been renewed once, putting him on year eight. The week prior, Lyle Sanders, the ancient professor of rhetoric and oldest black tenured faculty member, had quit the committee, sighting health concerns, which was just as well. He mostly slept through the meetings, his head dropping suddenly and freaking everybody out. Nnamdi was there to keep our number at a respectable two, we both figured. Solid build, neat, shoulder-length locs. Short, but cute. Horn-rimmed glasses, bowties or tweed vests over crisp, long-sleeve oxfords every day. A Kappa, I could tell before he told me so. Friendly enough. He said he liked my twist-out, called it glossy. I laughed, said thank you. He called me “sista” and I did not roll my eyes. By this time I’d also finally bought a microwave.

The following informational display has been approved:

A mounted poster highlighting the furniture and tools in the houses, including one kitchen table, one bed with a quilt similar in style to those sewn by Miss April during her tenure, one washing board, an embroidery hoop and one broom.

Items currently in the houses but hereafter prohibited from display:

– A hatchet, found hanging near the fireplace of House #1.

-Seventeen handmade dolls that comprised Miss April’s collection (some inherited from her mother), donated to the University by her sons.

-The 6-inch-by-12-inch wooden box with a cross carved into its top, found buried behind House #2 in 1983.

-All contexts of this box.

In consideration of the preservation of the approved objects for display, the Committee recommends that access to the interior of the houses be limited to scholars with written permission from the University’s Department of Special Collections, and various special persons as designated by the Board of Trustees. Visitors from the general population should view the interior of the houses from the front and back porches via the double-paned, shatter-proof windows.

A typical committee meeting went like this: We were all given a proposal for an element to be included in the restoration of the houses, then thirty minutes would be devoted to presentations regarding the merit of the proposal, sometimes made by the authors themselves, but more often from third-party experts. Then we’d deliberate for twenty minutes or so (usually less) and issue our recommendation. Patricia Dwyer, the head of the Office of the General Counsel, would then run the recommendation through whatever sort of legal analysis was necessary and return the next meeting with the proper wording for us to adopt. Pretty efficient, I thought. The catered lunch varied from sandwiches to Italian to Chinese.

The Committee acknowledges receipt of a petition presented by community member Shaw Hammers proposing that the site include literature about the translatlantic slave trade, including the amount paid for original inhabitants as listed in University archives.

Finding: Committee finds such literature to be outside the scope of the goals of the restoration project.

From the outset, Nnamdi had taken issue with the omission of the word “slave” and the use of “houses” over quarters or cabins. I was with him at first. I mean, if you don’t use it, that’s erasure, right? But then Becca Samuels from campus counseling services—the woman who swiped me in in the early days—finally stopped speaking in slogans and said something that made a little sense on the day we discussed the petition (it had two hundred signees, but only about eighty from people affiliated with the university, and most of those were classified staff). Becca asked: Would the relatively small population of students of color find comfort in these houses, or would they become fodder for ridicule used against them? She presented research about young people and constant proximity to sites of past trauma. “It can feel like stepping on the same land mine day after day just to get from one class to the next,” she concluded. This was more flourish than reality because the houses, being tucked up in the corner of campus like they were, weren’t on the way to anyone’s class.

Predictably, Patricia Dwyer rattled off a bunch of legalese that suggested the proposal could one day bankrupt the university. I didn’t care about Dwyer’s point, but Becca’s—it was worth mulling over, her land-mine analogy notwithstanding. Who am I to say what causes another person trauma? In the end I decided to show solidarity and vote with Nnamdi. We lost 2-6.

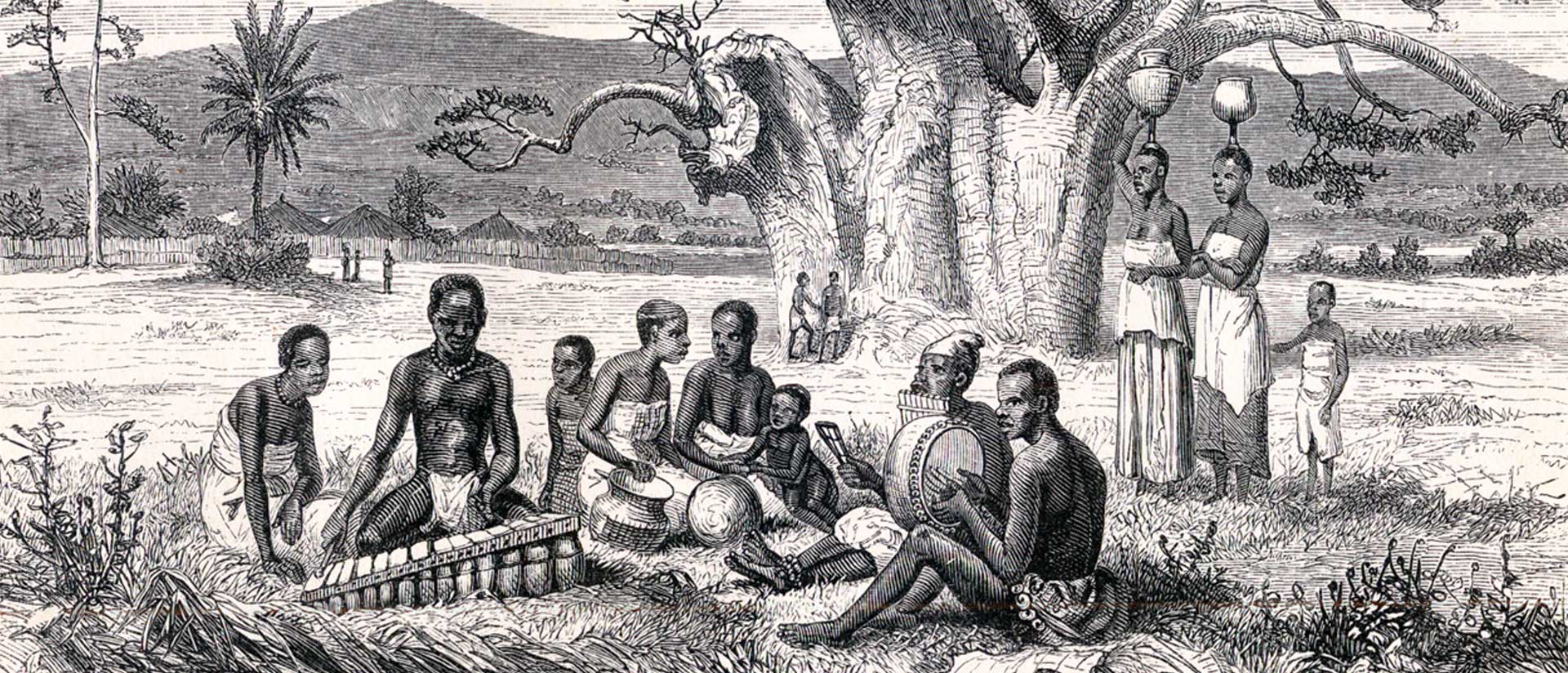

In accordance with a recommendation from expert linguists, the following language and accompanying illustrations* have been accepted by the Committee:

Lenny Roberts used the phrase “lee little” to mean very small. “Lee” is similar to a WOLOF words that means small.

One of the inhabitants of this House was named Esther Malink. MALINKE is the name of an ethnic group, also known as the Mandenka, the Mandinko, the Mandingo or the Manding.

To express amazement, inhabitant Buster Griggs would exclaim, “Great Da!” The FON people (also known as the Fon nu, the Agadja, or the Dahomey) worship a god named Da.

Miss April referred to peanuts as “pindas.” Pinda is the KONGO word for peanut. The Kongo people are the largest ethnic group in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

*Illustrations should show a map of West Africa with corresponding geographic regions of each ethnic group highlighted in either of the University’s official colors.

This linguist (there was only just the one—not plural), Dr. Nichole Valdes-James, made a very compelling argument. Even Nnamdi, who hated us all by now, had to admit it. Gander, the co-chair, looked charmed in spite of himself. Who can argue with enduring language? Who would see a posting like that and not be impressed, intrigued? Apparently, Nnamdi had expected plenty of people to be offended. After the meeting, he walked me back to the library. “A decade ago you hardly ever heard the word Africa on this campus, if not in the pejorative,” he said. I said, “Well, Africa’s pretty trendy up North these days.” He looked at me like I was an idiot, muttered, “This isn’t up North.” But then he invited me to get a drink with him.

The Committee recommends the following permanent information placards be added to the façade of the Miss April Houses wherever the restorers find aesthetically pleasing:

A display highlighting the restoration efforts of university researchers, with attending photographs of the process of transporting the cabins to their current location.

A display with the name of members of this Committee.

I left Brooklyn because I was at the point where just walking to the post office made me want to reach out for the nearest stranger’s neck and squeeze it, and I’m not a particularly violent person. All of these forever-children in wrinkled clothes with make-believe jobs and very real bank accounts looking down their noses at me, as if the sight of me made the neighborhood bad? I know, I know. But just because it’s happening all over the place doesn’t make it any easier to stomach. Plus, I was single again. Plus, all my friends were having kids and moving away, or just moving away because things had gotten so unbearable in Brooklyn. I was sitting at my desk at my branch library one day, with a stack of books to weed, and thought: “You know what? They can have this place.” I went online, applied for this job and got it, even though I don’t have any university experience. The air is much, much cleaner down here.

The Committee acknowledges receipt of a petition presented by community member Shaw Hammers, submitted on behalf of Nnamdi Watson, Visiting Lecturer in African-American Studies (and member of this same Committee, hereby recused from this vote) proposing an informational placard featuring scholarship speculating on how and against what odds particular words and phrases might have lasted in the inhabitants’ lexicon over the generations.

Finding: Committee finds that such a placard would be outside the scope of the goals of the restoration project.

It was stupid of the committee to accept proposals on a rolling basis. This was a policy established before I arrived. Of course Nnamdi would try to take the one thing everyone was enthusiastic about and flip it on them. I told him the night before to just leave it alone, be happy they don’t just bulldoze the houses altogether, but he said, “It’s the principal of the matter.” And I said, “That’s usually what someone says before they do something dumb,” and he shook his head and threatened to leave my apartment. But he didn’t. He didn’t leave the committee either. He came twice a week, ate heartily, and smiled too much at everyone there.

The following permanent placard must be affixed within twenty feet of the entrance of both Miss April Houses:

A display thanking the individual and corporate donors that made the restoration project possible. Language on this display is up to the donor’s discretion, granted such language meets the guidelines outlined above.

The semester was nearly over by the time we worked our way through all of the proposals. No, I didn’t let them put my name on the official committee placard. I was new and maybe I didn’t quite understand the stakes, but I knew better than to put my name on either one of those houses. They didn’t even ask me to explain why I abstained. No, I did not join Nnamdi, Shaw Hammers, and the seven others who staged a sit-in in for three days on the porch of House #1. That doesn’t mean I didn’t care.

If you focus on what we did accomplish as a committee, versus what was left out, we communicated two important truths: The past inhabitants made due with what they had—a few pieces of furniture, a humble kitchen—and they found ingenious, albeit small ways to make their language endure. That’s not nothing. That’s huge, I think.

And maybe a later committee can add more information.

This story appeared in It Occurs to Me That I Am America, edited by Jonathan Santlofer, published on January 16, 2018, from Touchstone, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, and was also published on Tin House’s website, on January 15, 2018. © 2018 by Angela Flournoy