Left Alone

Greta Garbo’s search for solitude

By Lois Banner

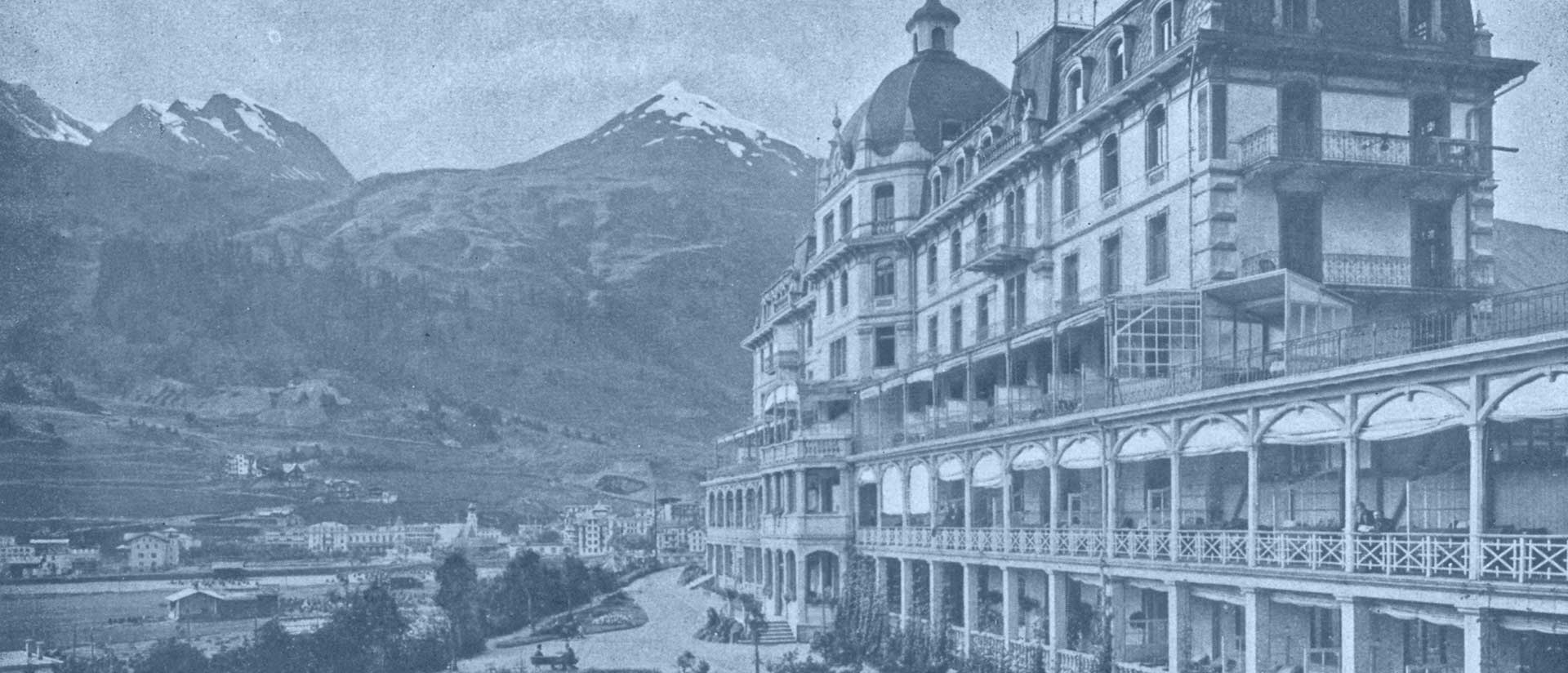

When screen star and legendary beauty Greta Garbo died, in 1990, at the age of 84, she was one of the most famous women in the world. She had become a top Hollywood star in 1926, at the age of 20, when she made the film Flesh and The Devil, less than a year after she came to Hollywood from Sweden. She retained that stature for 17 years, until 1941, when she retired from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), her studio, at the age of 36. She then moved to New York and made no more movies. Rather, whether by accident or design, she became a celebrity, famed as a leading member of the international “jet set,” led by Aristotle Onassis, the Greek shipping tycoon.

As a feminist and a scholar, I have long been fascinated by the histories of feminism and of beauty as well as by the lives of prominent women who defined and reflected the histories of their eras. Thus far, my biographical subjects have included Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who led the American woman suffrage movement in the nineteenth century; Margaret Mead, an anthropologist and public intellectual in the United States in the mid-twentieth century; and Marilyn Monroe, a Hollywood cinema star and symbol of beauty from the 1950s to the present. These three women form a disparate group, but their lives display similar themes: a sense of showmanship, a charismatic appeal to others, and a greater or lesser commitment to advancing women’s freedom.

Greta Garbo offers a special challenge. She lived much of her adult life in the era between the two world wars, when feminism seemed in the doldrums; she never identified herself with a feminist group; the majority of her audiences were in Europe, not in the United States; and many film scholars regard her as consistently playing in her films the ur-romantic heroine whose life revolves around love—and suffering—for a man. In his acclaimed history of Hollywood films, film scholar Lewis Jacobs described Garbo as “the prototype of the ultra-civilized, sleek and slender, knowing and disillusioned, restless and oversexed and neurotic woman who leads her own life.”

Garbo lived much of her adult life in the era between the two world wars, when feminism seemed in the doldrums; she never identified herself with a feminist group; the majority of her audiences were in Europe, not in the United States.

I began to crack that stereotype about Garbo when I determined that feminism in the interwar years differed from the women’s rights movement that went before it and the feminism that followed it. After woman’s suffrage was won—by 1921 in Germany, the Scandinavian countries, and the United States— many feminists turned from political and legal goals to focus on ending Victorian sex restrictions, in line with the sex revolution of the 1920s. They called for trial marriage, free love, free divorce, birth control, and “The Single Standard,” a slogan for ending the centuries-old double standard, under which men had sex with impunity, while women were supposed to remain virtuous.

In many of Garbo’s early movies, she plays a modern woman who challenges traditional moral values. Even though Hollywood censors required that they end by approving heterosexual monogamy, she is not punished for violating middle-class values. In 1929, she even starred in a movie called The Single Standard, written by feminist screenwriter Adela Rogers St. Johns. In that film, she travels on a yacht with a lover around the South Seas. In the end, she remains with a husband and a son she has acquired along the way, but she isn’t punished for having lived with a man to whom she wasn’t married.

Garbo’s early period of what might be called “proto-feminism” in her films culminated in Queen Christina, which she made in 1933. The movie is a biopic of the seventeenth-century Swedish queen who cross-dressed and was bisexual, pacifist, and reform-minded. Garbo later stated that the movie was as much about herself as about Christina. Garbo cross-dressed off the screen, considered herself to be more male than female, and was as responsible as film star Marlene Dietrich for making trousers popular among women, as well as turtle-necked sweaters, previously worn by jockeys and prizefighters.

Garbo cross-dressed off the screen, considered herself to be more male than female, and was as responsible as film star Marlene Dietrich for making trousers popular among women, as well as turtle-necked sweaters, previously worn by jockeys and prizefighters.

In contrast to all other MGM stars, she challenged the studio’s dictatorial head, Louis B. Mayer, by engaging in a seven-month sit-down strike after finishing Flesh and the Devil, to end her typecasting as a siren/vamp. She also demanded a new contract with a higher salary, input into choosing co-stars and directors, and the promise of dramatic roles. Given the huge box-office returns on Flesh and the Devil, Mayer gave in to Garbo’s demands; profits were his bottom line.

But her Hollywood career was never easy. In the 1920s era of ballyhoo and celebrity stalking, fans and street photographers wouldn’t let her alone. And she was the favorite subject of the Hollywood movie fan magazines, whose writers engaged in an endless debate about her appearance and her acting. Many of these writers celebrated her; some criticized her. When she came to Hollywood, in 1925—the first Swedish star to do so—small women with round eyes, baby faces, and tiny bodies were in fashion; Mary Pickford, hardly five feet tall, reigned supreme. Garbo was considered too tall—she was five feet seven inches. She had broad shoulders and a chunky body; she was built like a man. Extensive dieting on her part to meet the day’s fixation on thinness in women brought out her deep-set eyes, high cheekbones, and sunken cheeks. She looked more Slavic than Swedish. In 1930, one reporter called her “an anemic, over-slender girl, with straight and rather stringy tresses, a skin kissed to washed-out pallor by the cold Northern Lights, shoulders too broad and angular for her frame, oversized extremities.” Although Garbo and her cinematographers tried to hide these features, they are apparent in most of her films, including A Woman of Affairs (1928).

The racism of the 1920s was directed against her. Swedish immigrants to the United States were usually praised as a favored Nordic race, but an opposing belief held that they were lazy, dumb, and too tall. Slavic immigrants were attacked as dark-skinned peasants, and Garbo looked Slavic. All these epithets were directed against her, while quotations from her were published in a fractured Swedish. “I t’ink I go home,” a statement Garbo often made when she left a film set, became a national joke.

The racism of the 1920s was directed against her. Swedish immigrants to the United States were usually praised as a favored Nordic race, but an opposing belief held that they were lazy, dumb, and too tall.

Garbo was visited with a cacophony of conflicting opinions; some of her fans were so devoted to her that they were called “Garbo-Maniacs.” They dressed like her and wrote letters to the fan magazines defending her. Louis B. Mayer increased her salary until she was the highest paid woman in the United States. But Garbo, who was fixated on becoming wealthy because she had grown up in poverty, finally resigned from MGM and moved to New York. She became fed up with her inability to escape the fans who stalked her—even though she dressed in disguises—and with being cast in second-rate films.

After Queen Christina, she gave up trying to effect reform in Hollywood; she did what the studio wanted. She made period dramas in which she suffered over love of a man; the most famous was Camille, the story of a nineteenth-century tubercular French courtesan in love with a young man. In her period films, she was usually costumed in frilly feminine garb, which concealed her masculinity and quashed the many rumors that she was lesbian. Such behavior was forbidden by Hollywood’s draconian Moral Code, which was put into effect in 1934. Her period films and the femininity of her costumes in them propped up her reputation as “the world’s most beautiful” woman, a title MGM publicists bestowed on her.

Always suffering from shyness and melancholia, deeply afraid of strangers, in her later years Garbo found security among wealthy and titled friends. Beginning with the famed Swedish director Mauritz Stiller, who discovered her for films, she always had a mentor to guide her. In the 1930s and 1940s, Salka Viertel, an actress and screenwriter from Germany, served in that capacity, followed by Gayelord Hauser, the founder of the whole foods movement in the United States, and Georges Schlee, an emigre to the United States from the Russian Revolution. (She probably would have married Schlee, but he had a wife who wouldn’t agree to a divorce.)

A natural athlete, Garbo did yoga and pilates and walked the streets of the cities in which she lived. She was famed for doing that in New York. But she always had a friend along with her, and she often visited another friend for tea and snacks along the way. Those friends included Katharine Hepburn; Garbo was never a hermit. Nor did she say, “I want to be alone.” She contended that she always said, “I want to be left alone.”

Garbo was never a hermit. Nor did she say, “I want to be alone.” She contended that she always said, “I want to be left alone.”

Garbo found that the fame she had craved as a child and later achieved as an adolescent was a Frankenstein monster. Although she had moments of great happiness in her films and her friendships, her final judgment on her life is tragic. “The story of my life is about back entrances and side doors and secret elevators and other ways of getting in and out of places so that people won’t bother you,” she stated. And, from the age of seventeen until she died, she chain-smoked, suffering from many ailments smoking causes or worsens, from chronic bronchitis to weak circulation to her final death from kidney disease. In the final analysis, Garbo is a monument to hard work and artistic talent and to the appreciation and mistrust of female beauty in our modern world.

Image: Greta Garbo, 1933. Photo courtesy Les Archives du 7eme Art. Colorist: Olga Shirnina