Gate of Tears

Migration and impasse in Djibouti

by Nathalie Peutz

In October 2018, a Yemeni-Ethiopian refugee living in a camp in northern Djibouti showed me photographs of several corpses lying on the roadside just south of the camp. These were the bodies of Ethiopian men who had died that June of cholera or acute diarrhea after traversing Djibouti’s scorching desert on route to Yemen and, ultimately, Saudi Arabia and beyond. Although Ibrahim and his friends were incensed by the migrants’ ghastly deaths, they had long become inured to their routine presence in and around the Markazi camp for refugees from Yemen. Indeed, during a visit in January 2020, I observed tens of young Ethiopian migrants entering the camp daily through a gap in its chain-link fence. Many of them rifled through the camp’s overflowing garbage heaps, searching for food. Others walked among the narrow rows of the air-conditioned container homes that were donated by Saudi Arabia, begging the refugees for their leftovers. Some of the younger Ethiopians hung around the camp’s largest shop, eyeing its goods. Its Yemeni shopkeeper, continuing a charitable practice he had adopted during Ramadan, prepared large platters of rice daily that he shared with the migrants who congregated there. By and large, the refugees who had fled aerial bombings, military conscription, and a devastating humanitarian crisis in Yemen often try to help the Ethiopian migrants heading into the very warzone they escaped. It is not just that the“refugees” pity the “migrants” whose day-to-day travails seem even more precarious than their own; many of these refugees, who had themselves migrated previously between Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and the Horn of Africa, evaluate their own trajectories in light of these passersby.

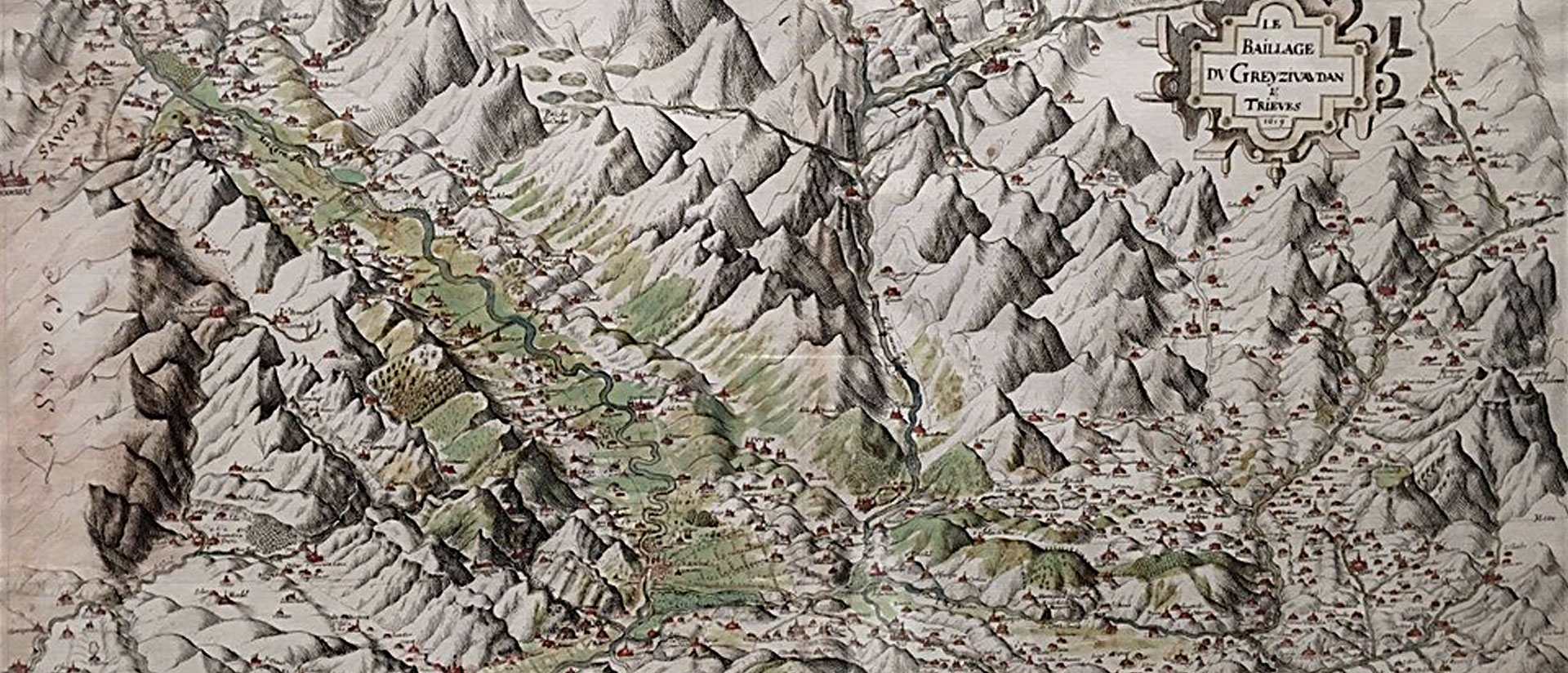

A crossroads for migration to and from the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, the Republic of Djibouti receives mixed and multidirectional migration flows of refugees, asylum seekers, economic migrants, environmental migrants, and other migrants moving both into and out of conflict. It is thus a productive site through which to examine the legal, political, racialized, and gendered distinctions drawn between refugees and migrants—both African and Arab—who often encounter, discriminate against, or marry one another; share trajectories; traverse these categories; and disrupt or re-enforce social hierarchies as they pursue “a future” through or within the confines of a fitful mobility.

A crossroads for migration to and from the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, the Republic of Djibouti receives mixed and multidirectional migration flows of refugees, asylum seekers, economic migrants, environmental migrants, and other migrants moving both into and out of conflict.

Albeit one of the poorest and smallest countries in the world (with a population of less than one million), Djibouti has one of the world’s highest number of refugees per capita. In addition to hosting nearly 30,000 refugees and asylum seekers from neighboring Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Yemen, Djibouti is a key transit country for migrants heading toward the Arabian Peninsula in search of work. Each year, tens of thousands of Oromo and Amhara walk across Djibouti’s arid desert and alongside its coastal highway toward the Red Sea towns of Tadjoura and Obock, where they are crowded onto wooden dhows crossing the Bab al-Mandab strait to Yemen: “the Gate of Tears.” If these Ethiopians do not drown, and if they are not imprisoned or held for ransom in Yemen, they continue their journey northward to Saudi Arabia. In 2018, approximately 160,000 migrants and asylum seekers crossed the Red Sea (departing from Djibouti) and the Gulf of Aden (departing from Somalia). In 2019, more than 138,000 migrants and asylum seekers entered Yemen. Notably, this was the second consecutive year that the number of migrants crossing the sea from the Horn of Africa to Yemen exceeded the number of migrants and refugees crossing the Mediterranean to Europe. In January 2020, another 11,000 migrants arrived in Yemen, 5,000 of them departing from the beaches north of Markazi. The following month, just before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, would see the number of migrant arrivals in Yemen reduced by as much as 90 percent (in part due to the closure of the Ethiopia-Djibouti border), the International Organization for Migration designated this Eastern Route “the busiest maritime migration route on earth.”

The Markazi refugee camp in northern Djibouti is located just five kilometers south of the town of Obock, where African migrants congregate before being trafficked across the Red Sea. The camp, one of three United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) camps in Djibouti, was established in April 2015 to accommodate the influx of refugees arriving from Yemen following the eruption of the civil war and its regional escalation, in March 2015. Since then, more than 3.6 million people have been displaced within Yemen and more than 24 million people (out of a population of 29 million) require some form of humanitarian assistance. By comparison, the numbers of refugees and asylum seekers who fled Yemen are relatively small—indicative, perhaps, of how difficult it has been for many Yemenis to leave their country due to airport closures, mobility restrictions, and lack of financial resources. Still, by October 2017, at least 190,000 refugees and asylum seekers had fled to neighboring countries, including some 38,000 Yemeni nationals who entered Djibouti, from where the majority sought onward passage to other destinations. Over the past five years, the number of registered Yemeni refugees remaining in Djibouti has hovered between 4,000 and 7,000 individuals divided between its capital, Djibouti city, and the Markazi camp.

Situated directly across the street from the Markazi refugee camp is a Migration Response Center, run by the International Organization for Migration. Established in 2011 and rehabilitated in 2017, the center assists and helps to repatriate migrants returning to their home countries. Some of the migrants temporarily sheltered by the center had worked previously in Saudi Arabia but were deported; some had made it to Yemen but were captured by Houthi forces and held for ransom; some were abandoned in the Djiboutian desert by their smugglers. At times, the number of migrants seeking assistance exceeds the center’s capacity to house them; then, for each group of Ethiopians repatriated to their country, another group is waiting and sleeping outside. It is the refugee camp across the street that provides both aspiring and returning migrants with additional sustenance and diversion.

At times, the number of migrants seeking assistance exceeds the center’s capacity to house them; then, for each group of Ethiopians repatriated to their country, another group is waiting and sleeping outside.

The refugees I have come to know during the course of my research in Djibouti share more than these geographical coordinates and their food rations with the Ethiopian migrants. Many had also worked as labor migrants in Saudi Arabia or had migrated repeatedly between Yemen and the Horn of Africa. Nasir, the shopkeeper who prepared meals for the Ethiopians, had been part of the mass exodus of some 800,000 Yemeni migrants who had been forced to leave Saudi Arabia and Kuwait during the Gulf crisis in 1990–91; others had lost their jobs and were expelled from Saudi Arabia at the outset of the current war. Moreover, as many as a third of the refugees living in the Markazi camp until recently are the descendants of Yemeni men who had migrated to Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, or Djibouti in the early twentieth century to escape desperate conditions in Yemen. Their children, born of African women, returned to Yemen to flee warfare or anti-Arab discrimination in the Horn. And it is their African-Yemeni grandchildren, anxious to escape the marginalization and alienation they suffered in Yemen, who are now refugees in Djibouti, Somalia, and Ethiopia.

Ibrahim, the Yemeni-Ethiopian man who showed me the photographs of the deceased migrants, is the son of a Yemeni man who had migrated to Harar, Ethiopia, where he married a local Oromo woman. When Ibrahim’s “Arab-owned” pharmacy was burned down by Oromo nationalists, he moved to Sanaa, Yemen, where he married an Ethiopian-Yemeni woman from Harar and began his life anew. In 2015, fearing that their eldest sons would be conscripted by the Houthis, they fled to Djibouti. Like many other new arrivals in Markazi, Ibrahim and his family hoped that their refugee cards would lead to third-country resettlement: an escape from this generational circuit of displacement and alienation. To be clear, most of these refugees from Yemen were fleeing the acute brutalities of war: bombs dropping on their neighborhoods; missiles hitting their loved ones at distribution points; Houthi rebels threatening to conscript their sons; corpses lying in the streets. At the same time, for Ibrahim and many other socioeconomically and politically marginalized Yemenis, the occasion to become a bona fide refugee with international protection and the prospects for third-country resettlement was a risk worth fleeing for.

In keeping with its openness toward refugees, the Republic of Djibouti is one of a dozen nations worldwide to pilot the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework laid out by the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants in 2016 and eventually adopted as part of the Global Compact on Refugees by the United Nations General Assembly in December 2018. Although the Compact calls for increased support for third-country resettlement and voluntary repatriation, it also aims to enhance refugee self-reliance and to ease pressures on host countries located in the Global South. Described as “a new deal for refugees,” the Compact thus endorses the greater inclusion of refugees within their host societies through improved access to education and employment. To this end, the Government of Djibouti—which had already extended prima facie recognition to refugees from Somalia and Yemen—has taken substantive steps toward socioeconomically “integrating” refugees into the surrounding communities. In January 2017, Djibouti’s President Guelleh promulgated new refugee laws aiming to safeguard and strengthen the refugees’ access to education, healthcare, employment, and eventual naturalization. Most immediately, these laws paved the way for the inclusion of refugees in the national health and education systems—a move that, in the realm of education, will enable refugees following the Djiboutian curriculum to receive nationally recognized certificates to facilitate their employment. In December 2017, these new laws came into effect by presidential decree. And, to much UNHCR fanfare, the government announced that the country’s camps would henceforth be considered “villages.” In fact, in the Markazi camp/village, this semantic shift was accompanied by the refugees’ move from what had been temporary shelters to the more durable container homes donated by Saudi Arabia’s King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Center.

In keeping with its openness toward refugees, the Republic of Djibouti is one of a dozen nations worldwide to pilot the Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework laid out by the New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants in 2016 and eventually adopted as part of the Global Compact on Refugees by the United Nations General Assembly in December 2018.

In theory, Djibouti’s implementation of the Framework provisions would help shift support from the parallel structures created for its refugee population to its national educational and health services, which are now available to all. In practice, however, the transition away from NGO-led services has reduced the refugees’ access to good medical care within the camp as well as their ability to shape their children’s education. Whereas initially the development of what is now officially designated “the Saudi village” appeared to provide support for the UNHCR’s push for local integration, its viability is increasingly unclear. Many of the refugees feared that if they were to move physically from their impermanent tents to these durable containers they would be moving jurisdictionally from the tent of United Nations protection to the de facto prison of permanent displacement. Moreover, the increase in Saudi humanitarian aid to Markazi portends to create yet another parallel system. Rather than being “integrated” within national institutions or within the nearby town, the refugees living in the gated and air-conditioned Saudi village may become even more isolated from the local environment and more dependent on outside assistance than they were before. For those who yearn to be resettled in countries such as Sweden or Canada, these houses are nothing more than a gilded cage. Even were the Framework to meet its lofty goals, the refugees I interviewed do not trust that they will ever be “integrated” in a region from which they, their parents, or their grandparents once fled. In the view of the “marginalized” (often racialized as black) Yemenis born to Yemeni fathers and Somali, Ethiopian, or Eritrean mothers, neither Yemen nor the countries in the Horn of Africa had ever fully included or accepted them. It is for this reason that they crossed the sea, yet again, to become refugees: refugees who, through the prospect of third-country resettlement, could leverage themselves out of this regional migratory circuit and into a more open world.

And so, with integration signaling a new kind of impasse, the refugees from Yemen are taking cues from the migrants heading toward Yemen. Despite recognizing their material and legal privileges as “refugees”—relative to their own past experiences as migrants and to the conspicuous hardships of the “migrants” passing by—many have come to realize the increasing devaluation of refugee status in today’s inhospitable world. With dwindling hope for third-country resettlement, one of the only ways to escape permanent and effectively captive displacement is through movement. One of the men I know waxes philosophical on this theme: “To migrate is to know God,” he tells me. Migrating through the world is a way of venerating it. Despite the ongoing armed conflict and the increasing risk of the country sliding into famine, many refugees have returned to Yemen. Boarding cattle boats from the port of Obock, they cautiously embark on the Eastern Route: the route into the war. “Here, we are dying slowly,” several men and women have told me. “In Yemen, I’ll die quickly but at home.” One group of five young Yemeni men decided to join the African migrants heading northward to Europe. They flew to Khartoum, where they paid human traffickers to truck them across the desert into Libya. After two years in transit, including imprisonment in Libya, they boarded a dinghy to cross the Mediterranean and landed in Malta. Currently, they are seeking asylum in northern Europe.

Ibrahim’s Ethiopian-Yemeni wife had become so fed up with life in the camp that she paid a smuggler to take her and her young sons to Ethiopia—walking against the flow of the Ethiopians headed toward the Gate of Tears. Unable to support her children in Ethiopia, she took them to Yemen, where she opened a small shop. After a few months in Sanaa and renewed fears that her eldest son was in danger of being pulled into the conflict, she brought them back to Obock to live with Ibrahim as she again crossed the border into Ethiopia to pursue family reunification through a cousin in Canada. Their decisions and so many of the refugees’ and other migrants’ trajectories can be characterized by what Lauren Berlant (2011) calls “cruel optimism”: in this case, the fantasy for a better life that is the very obstacle to its achievement. Bound by the “cruel optimism” that his refugee status would eventually open doors to his family’s resettlement, Ibrahim refused to leave the camp. He did not want his sons to grow up in Ethiopia, from where he feared they would eventually be compelled to migrate, like the young Oromo boys who sifted through the camp’s garbage for its scraps. Tragically, Ibrahim suffered a stroke in the autumn of 2019 and was brought back to Ethiopia to die. It is not inconceivable that his sons—once refugees in

Djibouti, now refugees in Ethiopia— will one day embark as migrants on the Eastern route to Saudi Arabia, possibly passing by the camp in which they once lived. In this climate, the UN Global Compact for Refugees reads less like a global commitment than it does a form of Southern captivity and Northern abandonment. To the extent that there is a refugee “crisis”—as opposed to a mobility deficit—it is that this “new deal for refugees” may erect a new and more pernicious form of encampment.