Franklin, 1969

Fiction by Ayana Mathis

A sampan appears. Low to the black water and grenade distance from my post on the shore, it sails out of the mist that descended at nightfall.

Yesterday morning, I was given my assignment: I am one of a ten-man squad to be deployed to an island at the edge of a large bay. I’ll keep watch on the beach while the others plant mines. We sail out at 04:00. In the briefing, I was told to look out for indigenous vessels, junks, and sampans. Later that day, Pinky and Mills and I were walking to the chow hall when the Lieutenant yelledover his shoulder, “Seaman Shepherd! Don’t fuck this up.” Mills and Pinky laughed. Pinky said, “You can’t watch for sampans on the bay at night.” I asked why and all he said was, “You’ll see.”

Three men ride in the sampan, two at either end and one in the middle; the conical peaks of their paddy hats are pressed close to their heads. They paddle out of an inlet at the far end of the beach. Their arms move in graceful downward arcs. The one sitting in the middle trails his hand along the surface of the bay. Between his legs a large sack of something heavy and soft is creased in the middle and slumping over on itself. The sampan is black and wooden, less than two feet high with ends that turn up like a banana’s. The men sit straight as toothpicks, squinting against the beam from my flashlight. The boat does not list.

I fire two warning shots in the air.

“Identify yourselves!”

The men in the boat throw up their hands and in their haste one of their oars falls into the water.

Fishermen in sampans are not to be trusted. In our briefing, the Lieutenant said it should not always be assumed that they are fisherman. They paddle along in that quiet way they have, then reach under their bundles of fishing net and pull out grenades or MAC-10s.

“Stand up! Stand up with your hands in the air.”

I hear the wet suck of boot falls on the sand behind me. Mills yells, “Drop it! Fucking drop it!” even though none of the men in the boat is carrying anything.

First one stands and then another. The boat trembles and lurches. They look at us like we are a bunch of wilding monkeys.

“What’s in the sack?” I call. They don’t respond.

“They don’t speak English.” Mills says.

“They understand, they’re faking. “Dump the sack!” I motion toward the bundle with the butt of my rifle.

I fire another warning shot, this one into the water near the sampan. The man at one end reaches down and heaves the sack over the side. It sinks silently into the bay.

“Move along! Fucking move!” I say.

“Shit, Shep. They leaving!” Mills says.

“Get the fuck out of here!” I shout once more, though one of the fisherman has begun to paddle with the remaining oar and the sampan is creeping forward. Mills walks away, shaking his head.

In a few hours, we’ll have completed our mission and then we’ll load up the junk and sail away from here. Behind me, my squad is busy digging holes in the beach. I lived near a butcher when I first got married. He was always working whenever I walked by. He hummed while he worked. He was a happy man. Listening to the shovels pushing wetly through the sand, I remembered the sound of his knife cutting through flesh.

I am afraid that the mist over the water will creep onto shore and settle over the sand so that I can’t see snakes coming toward me. My neck aches with the strain of scanning the sand for them. I squeeze the trigger of my rifle, softly, slowly until I feel the pressure building under my fingertip, until I am a fraction of a second away from the satisfying pop of the trigger’s release. I light another cigarette. I have written a letter to my wife—my ex-wife, I suppose I should call her—our first communication in over a year. My Sissy. She’s back in Philadelphia. I think she’s really finished with me this time. I’ll never be finished with her.

When we crossed the threshold into our apartment on the day that we got married, a maple leaf blew into the living room. It had turned a deep crimson that darkened to burgundy around the edges. Sissy said that the fall was all blood and gold and I held the leaf and said, “Well, here we got the blood.” We went back outside to look for the gold. I found a yellow leaf on the sidewalk across the street, not a speck of brown on it. I can’t imagine doing that with anyone else— something as silly as looking for fallen leaves in the street, but with her it wasn’t silly at all. I gave her that gold leaf and she put it on top of the red one inside of a handkerchief that she pressed into a flat, neat square with the iron. We didn’t have any ribbon, so she cut a scrap from the lining of the dress she got married in and she tied up that handkerchief. That was only two years ago.

I don’t know where Mills gets all of this beer. We’ve been drinking since reveille. I smell like stale

cigarette smoke and rancid meat. I taste the smell in my mouth—my tongue and teeth are mossy. I ate a can of tuna earlier, and some crackers; my other meals were beer and coffee. I am always nauseous, I can’t remember the last time I went an entire day without feeling like vomiting. My beard has grown in irregular patches, beneath the hairs, red bumps flare in clusters.

I’d like to think Sissy wouldn’t recognize me, but that’s a lie. She’s seen me this ugly. When I get back to the ship I’ll start a new regimen: I’ll limit my beers to the evening after chow, I’ll stay out of fights and the brig. I think that I can do that, get myself together. I’ve done it before, though sometimes I think I am just a bleary drunk, and the periods when I am clean and shaved and useful, I am only hiding from myself.

I got a letter from Sissy last week. She wrote: You have a baby girl, born September 13th. I wasn’t going to tell you but she looks just like you, down to the flecks of hazel in her eyes. I don’t know what you’re going to do now that I’ve told you, I don’t know if I want you to do anything. I was going to keep the secret but I know enough to understand that the things you try to hide come out when you least expect them to. I don’t want my baby to have a liar for a mother. She is five months old. Her name is Lucille.

A year ago, I went to see Sissy on my leave. She’d taken up with some cat after she left me. The two of them were living in a little place on a block in West Philadelphia where neither of them knew anybody. I wore my dress blues. The brass buttons shone in the sun. I felt like the son of a king come to claim his bride. I didn’t deserve to feel that way, it was a lie, but the fantasy helped me keep my head up. As I climbed the steps to the apartment I realized that it was remarkable that Sissy hadn’t found another man before now. I’ll tell her, I thought, that I had come to offer her a divorce. We could go down to the courthouse that same afternoon. I’d free her so she could have an honorable life with this man she’d found. But then she opened the door and she was every inch my Sissy, with the mole on her cheek and her iron gaze.

“I came to get you,” I said.

She stood on the threshold looking at me and blinking quickly. I thought she might cry, but she wouldn’t give me the satisfaction.

“We’re still married,” I said. “What kind of way is this to live?”

“I’m living like a woman, Franklin,” she answered. “My mother and my sisters won’t speak to me, but it’s worth it to live like a woman. I don’t know when you suddenly got so concerned about my sacrifices.”

And there we were in a movie with me as the penitent husband and Sissy as the wronged wife. I said my lines and she said hers. I don’t know why I didn’t take my hat and go.

“I came because I love you,” I said.

“I believe you think that’s true,” Sissy said.

She never moved from the doorway. Her hands hung at her sides and she made little fists then released them again like she did when she was nervous. Little circles of gold, the sunlight reflecting off of my brass buttons, played across her face. I looked over her shoulder into the living room. It looked all right; it was cozy. Everything in the room was light and lifting, white curtains, a cream sofa, a pale rug on the floor.

“I’m a better man after being in the service.” I knew better than to say that to her, but I couldn’t think of anything else. “I arranged for a truck to help you move your things. I can call right now, it’d be here in ten minutes.”

“A truck!” Sissy laughed in spite of herself.

She knew I didn’t have a truck. I don’t know what I would have done if she’d agreed.

“A truck!” she said again and shook her head.

She let me into the apartment. I sat on her white couch. She sat opposite me in a straight back chair with wooden armrests.

“I haven’t had a drink for days,” I said.

“I can’t go with you this time, Franklin.”

“So you’re just going to live like this with this man!”

“You wore me out, Franklin.”

I caught my reflection in the living room window. I looked like a pile of fool’s gold, you had to squint from all the shine coming off of me—buttons, shoes, epaulettes. I asked myself why

I wanted her back so badly. I couldn’t answer the question, but I couldn’t leave that apartment either.

I got up from my place on the couch and stood crying in the middle of the room.

“I love you,” I said.

“We have to be finished, Franklin.”

She got up and took my hand. I didn’t understand how she could hold my hand like that and tell me no. She stroked my palm with her fingers. I leaned into her because I needed some strength to walk out of that door and she was the only one I could get it from. We hugged for a long time and then I kissed her neck, and her shoulder. I kissed her eyelids and the hollow between her collarbones and we sank down onto that white couch together.

After, while she was buttoning her blouse, she said she’d walk me out to the corner, and you know we walked out to that corner holding hands like we did when we were dating, before I messed everything up.

“You take care of yourself,” she said and turned quickly toward the house before I could reply. That was a year ago. I have not heard from Sissy since then—until I got her letter about Lucille.

We steer the junk toward the gulf. It’s slow moving, but we are making distance. The stars and fog fade in the pre-dawn and the sky brightens. Behind us the island is a ridged black silhouette, ever receding. A sampan glides along the surface of the water near the shore of the island. Probably a fishing boat, they come out at this hour. The occupants, a boy and an old man, look into the water and then at us. The boy is pointing at our junk, at me, I swear he’s pointing right at me. The old man pushes the kid’s arm down.

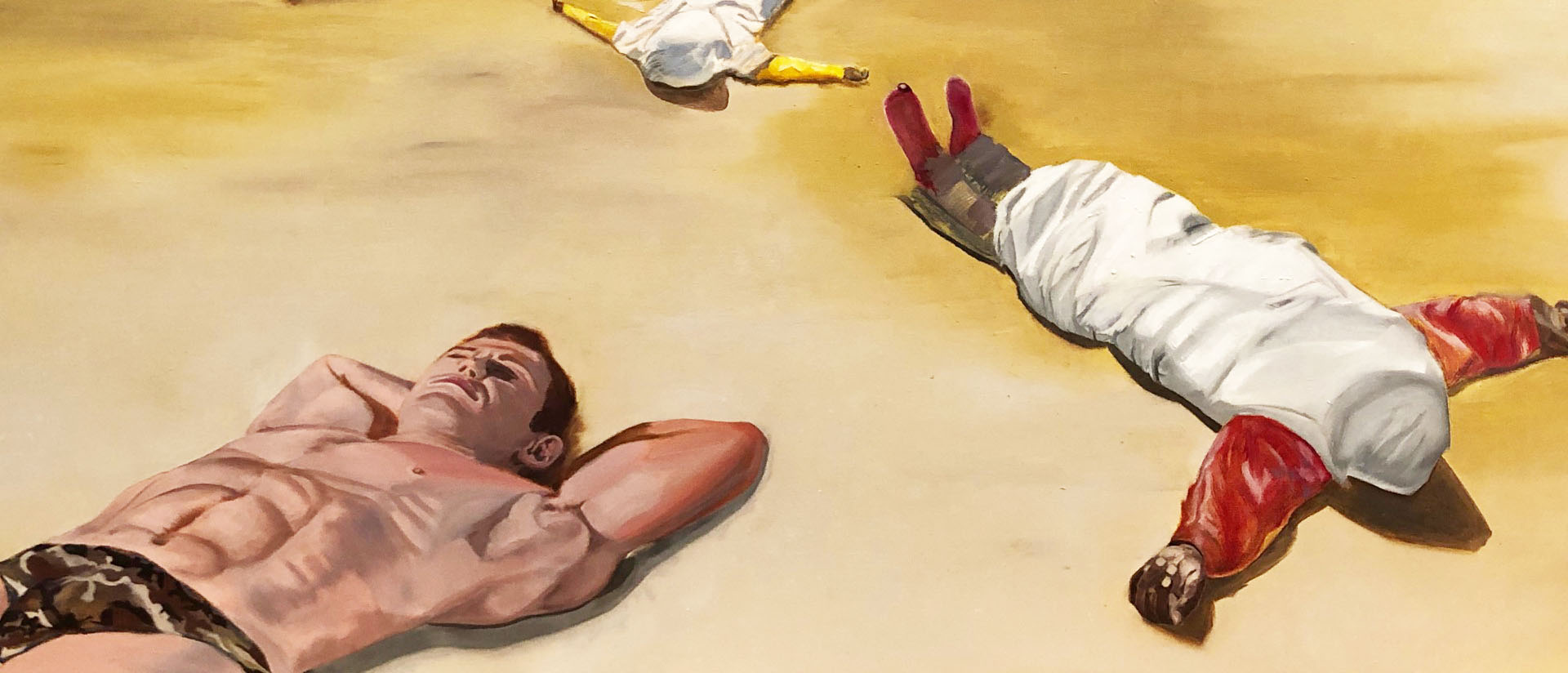

The sampan is lifted on a low wave, gently, like a ballet dancer lifting his partner, and pushed closer to the island. There is a boom. The boat is lifted higher on an upward moving column of water. The explosion echoes and echoes, it bounces from one island to the next. It knocks in my brain and chest. I am holding my breath but do not notice until it is quiet again and I take a deep inhale that makes me cough and sputter. Mills lets out a low whistle, says softly, “Shit.”

I get another beer and drink half in one gulp. We will get back to the ship in two hours. I look into the water for floating body parts. I want to see the boy’s head. I ought to be forced to acknowledge what I have done. Most of my missions are at night. I shoot into the darkness and sail away before I have to count bodies. It was the same with Sissy. I was a violence in her life and left before I had to face the damage I’d done; with Lucille there would be more recklessness, more hurt, more promises I don’t keep, more destroying the people I love.

I make a wager: if I see any evidence of the boy’s life we took I will never drink again. I set my beer on the deck and wait. I scan the water. A light-colored unrecognizable something floats toward me. I lean so far over the starboard side I nearly topple into the water. Behind me Pinky calls, “Suicide ain’t the answer!” I hear a round of guffaws. I lean and squint. The floating object appears to be a finger, then a leaf, then a discarded bandage. The current shifts and the thing is carried away from me. I pick up my beer, finish it off. When we get back to the ship I’ll go to sleep and when I wake up I’ll have the shakes and I won’t have the will power to sit on my bunk sweating and throwing up until the liquor’s out of my system. I’ll take a swig of the whiskey stashed in my footlocker and the days will go on as they’ve been. And it’s not like I don’t know I bet my family life on an exploded boy’s body parts. I know that, I know what it means about the kind of man I have become. Or always was? I can’t quite tell anymore. It is almost a relief to know that the people I love are free of me, that I don’t have to lie to myself, that I don’t have to pretend that Lucille would be better off for knowing me.

I reach into my pocket and throw my letter for Sissy into the bay. There was a picture in the envelope, which lands in the water next to the folded paper swan. In the photo I am standing at the dock with my ship behind me. I’m in my dress blues with my white hat pulled low over one eye. On the back of the photo it says: For you and little Lucille. Love, Franklin. Saigon, 1969.

From THE TWELVE TRIBES OF HATTIE: A novel by Ayana Mathis. Reprinted by permission of Vintage Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright c 2013 by Ayana Mathis.