Becoming a White Man in the Theater

by P. Carl

Last year, the online platform Howlround I help to run published an article by a group of distinguished women—theater practitioners and scholars—about the inherent bias in criticism in American theater that is primarily written by white men. The article was not a personal attack on any single individual; it states quite clearly: “The complaint is not personal; in other words: it is structural. Individual critics are ‘not the enemy.’” The article then implores, “We need a more expansive and informed notion of how critics come to decide what is ‘good,’ and a more honest conversation about why ‘good’ is often associated with plays by and about white men.”

As someone who was part of the conversation to publish the piece, I didn’t think this was such a radical provocation. We know that the field of criticism is dominated by white men. This is especially true of the first-line theater critics in many cities and, of course, in New York. Also, the idea that structural bias exists is hardly new. In fact, we have an entire country struggling with this issue right now. Further, that there is a thing called “patriarchy” didn’t seem that radical to me either.

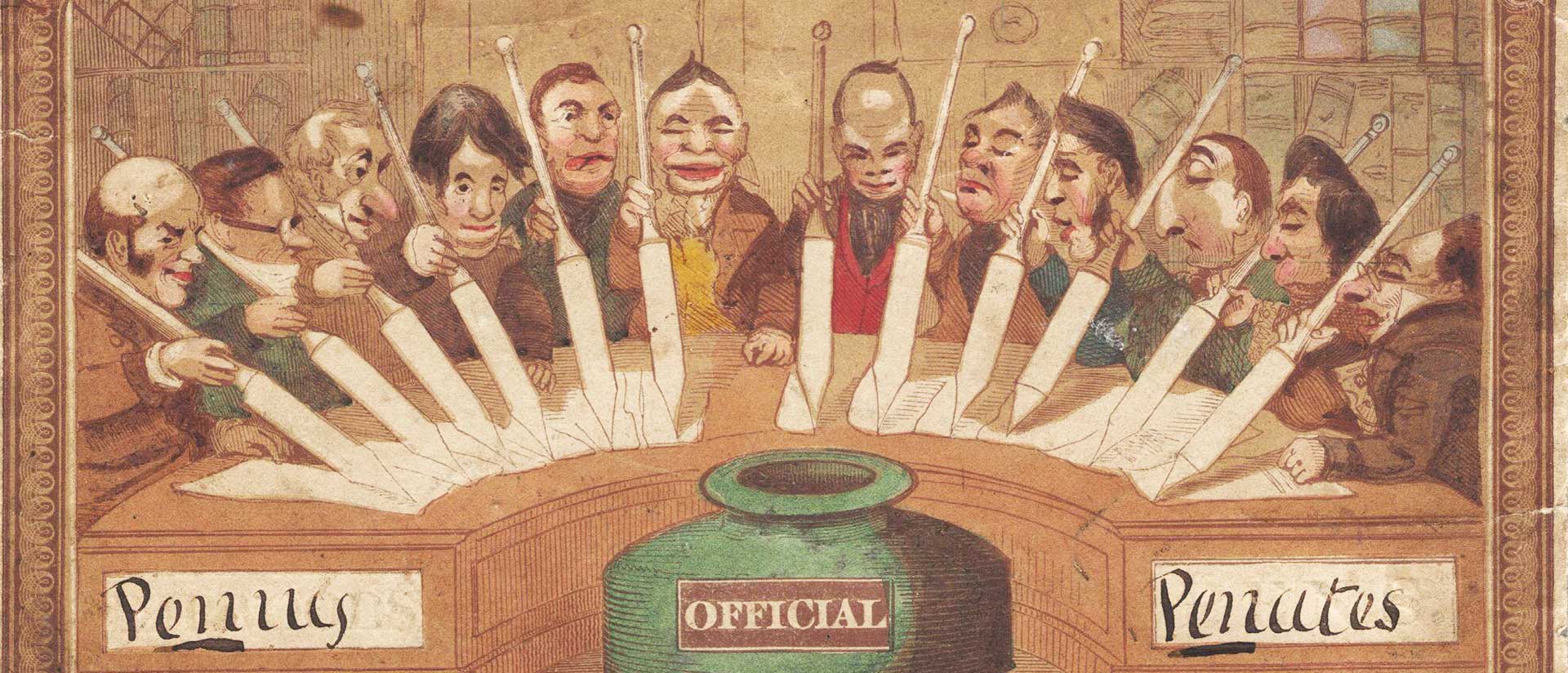

But 252 online comments later, I saw that it was. Many white male commentators responded defensively. Chris Jones, a leading Chicago theater critic, responded in the Chicago Tribune, further contemplating the pitfalls of the democratization of the arts, asking ultimately how he and other gatekeepers will get paid if everyone can have an opinion about what is “good”:

Alas, this new radical democratization threatens critics, just as it does well-paid artistic directors, executive directors, curators and all kinds of other gatekeeper types in the cultural universe, which explains why some say we/they react defensively . . . to any grassroots rebellion.

For Jones and others, it is interesting that democratization feels like a form of rebellion rather than a way of being inclusive. When we dare to point out structural bias and to question the professional establishment, we are performing acts of consciousness. When we choose to refer to acts of consciousness as acts of rebellion, the demand for democratization gets too easily reduced to personal attacks, and can be dismissed as lacking empathy. The demand for democratization isn’t rebellious, but rather our responsibility as citizens — to push our field to be more representative of the America we live in. The “gatekeeper types” have represented a small and exclusive part of our democracy and we must be challenged, and we don’t have to react defensively. Rather, we might have to feel the precariousness that women and trans people and people of color know so very well.

This has been for me an inexplicable year of seeing the world in a completely different way: I have gone through a gender transition. I joined a club. I became a white man. And, as I like to jokingly say, I picked a really complicated time to become me — despite popular opinion, trans wasn’t a choice for me.

By becoming myself, I entered a world of privilege I knew nothing about, a world I had heard about for sure but one I could have never imagined. Don’t get me wrong, being a trans guy is super complex and filled with a million discriminations — just try navigating the healthcare system for example. And I have news for you: the American theater is really transphobic. Landmines of micro-aggressions blow up in every direction, even from open-minded, socially conscious individuals. I have been stunned at the level of discrimination I have faced trying to transition.

One day I was ambiguous to the world, sometimes “he” and sometimes “she” . . . and then one day I was a man. What happened? What is that thin line that makes clarity for us between “he” and “she”?

Once I started to walk through the world as a white man, everything changed in my day-to-day reality. Now, those who encounter me for the first time don’t know I’m trans. Guess what? This white man’s world is a world of incredible daily privileges. It’s a world that I would describe as the opposite of one filled with micro-aggressions; a world where things just get handed to you without even asking. The first weekend I was in New York as a man, I had people waiting on me at the hotel in a way I had never experienced before. A waiter forgot to bring my orange juice and gave me free breakfast the rest of the week. I went into a store to buy a suit jacket the following week in Boston and had several male employees try to help me. (I have a long history of buying men’s clothes before the transition, and good luck getting anyone to look at you!) When I went to pay, the clerk asked me if the jacket was on sale and I said no. He let me know that it would likely go on sale so he would just give me half off. Other white men treat me in an entirely different way. It’s a strange kind of warmth, a lot of “hey buddy, how’s it going?” And then there is riding around in a Lyft. Who knew men talk a lot? They talk a lot to other men, I guess. They sometimes talk about women in ways that make me cringe, they talk about sports, and cars and politics and culture, but, in general, I notice getting around is more relaxing, less threatening. It’s just easy to get from here to there in a way it never was before. It’s so many small privileges that you would never notice them unless you never had them before. This is called structural bias, and if you’ve benefitted from it you are unlikely to know it because it’s not a privilege you’ve personally asked for, it’s just been handed to you as you move around the world.

Another thing I notice as a guy: men, and not just white men, use their privilege all the time in the theater. Somehow I can see this so much more clearly when I’m not the victim of it. They constantly interrupt women. They generally think their point of view is more informed and they never hesitate to jump in and speak up and let you know this. And white men specifically have no idea the ways in which navigating the world of work in the theater is just easier for them. They don’t think they should experience obstacles and seemed shocked when things that happen to women and people of color all the time, happen to them. The men I’ve seen behave this way aren’t individually bad people, they take advantage of the privilege that has been handed to them but too often they do so unaware, and get defensive when they are called on it. In this universe, is it any surprise that white men would step in to lead the way as arbiters of art (as critics and artistic directors)? They so fully trust their point of view, of course they would think it valid and informed and open-minded. This field is filled with misogyny. I couldn’t see this as clearly until I stopped sitting in its way.

I see the current mess we’re in — this radical moment where we no longer accept certain truths about art as conveyed to us by the gatekeepers—as an opportunity to lead the way toward a new America. The arts can actually push us forward here because imagination is one of the things we will need to create a new reality in our institutions (artistic and critical) that serves as an invitation to our radically diverse communities. Theater belongs to us all, women and trans people and people of color all belong on Broadway, and we should all get to participate in the economic reality that has been the sole property of white men for too long. Democratization isn’t the death of excellence and professionalism and expertise, it is the evolution of it. It is the beginning of new ways for us to live and experience culture together and to advance the medium we love to new heights.

For this shift to occur, those bemoaning inclusion as a potential threat and loss have to gain a new level of self-awareness about how they have benefitted from and wielded their privilege. In the ways that those of us denied privilege for so long have had to adapt to untenable circumstances— well, white guys, we might have to stop interrupting all the time and listen and feel uncomfortable.

A longer version of this essay was first published in 2017 on Howlround.com, an online platform for theater-makers worldwide. Reprinted with permission.