Premonition

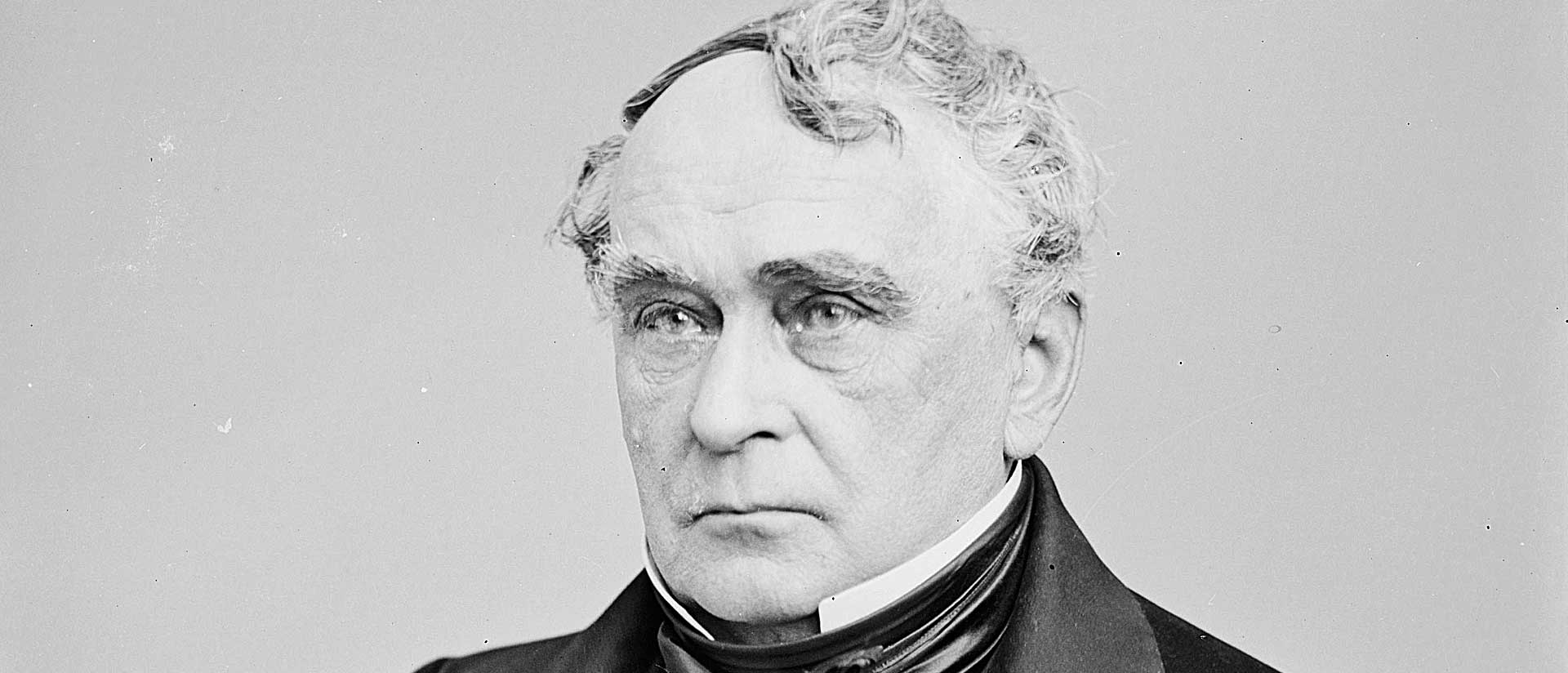

Lincoln, Booth, and Macbeth

By James Shapiro

ABRAHAM LINCOLN SPENT April 9, 1865—five days before he was assassinated—aboard the steamboat River Queen, sailing back to Washington after a risky visit to the front, including a tour of the now liberated capital of the Confederacy, Richmond, where fires were still burning. Lightly guarded and accompanied by his son Tad as he entered Richmond, Lincoln was mobbed by newly freed slaves. He then proceeded to the “Confederate White House” and sat in the office of Jefferson Davis, who had fled the city. It was a gesture that sat poorly with those embittered by its symbolism; John Wilkes Booth was maddened by it, having heard rumors that Lincoln had spat tobacco juice while lounging on Davis’s chair. After leaving Richmond, Lincoln made his way to City Point, Virginia, where, awaiting news from General Grant, he visited wounded Union soldiers for five hours, shaking hands with thousands of them. Though Lincoln did not yet know it, as he was sailing back to Washington, Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, all but bringing the war to an end.

One of those who journeyed home with him on the River Queen was Senator Charles Sumner, who recalled how Lincoln’s thoughts at this moment turned to Shakespeare, and to Macbeth in particular, as the president pulled out a handsome quarto of the play that he brought with him and twice read aloud “the tribute to the murdered Duncan.” Sumner was accompanied by a young Frenchman, the Marquis de Chambrun, whose diary entry for that day offers a fuller account of what took place: “Mr. Lincoln read to us for several hours passages taken from Shakespeare. Most of these were from Macbeth, and in particular the verses which follow Duncan’s assassination. I cannot recall this reading without being awed at the remembrance, when Macbeth became king after the murder of Duncan, he fell a prey to the most horrible torments of mind.” In his usual way, “Lincoln paused here while reading and began to explain to us how true a description of the murderer that one was, when, the dark deed achieved, its tortured perpetrator came to envy the sleep of his victim; and he read over again the same scene”:

Methought I heard a voice cry “Sleep no more! Macbeth does murder sleep,” the innocent sleep, Sleep that knits up the ravelled sleeve of care, The death of each day’s life, sore labour’s bath, Balm of hurt minds, great nature’s second course, Chief nourisher in life’s feast . . .

A more arrogant leader might have quoted Malcolm’s victorious lines at play’s end, having triumphed on the battlefield: “and what needful else / That calls upon us, by the grace of Grace, / We will perform in measure, time and place.” But Lincoln chose instead to dwell upon how perfectly Shakespeare had captured the unrelieved guilt of the “tortured perpetrator.”

Lincoln had told the actor Charlotte Cushman that Macbeth was his “favorite play,” and in his letter to the Actor James Hackett, he wrote that “I think nothing equals Macbeth; I think it is wonderful.” Lincoln seems to have found comfort reciting from this dark tragedy. That at least was the impression of John W. Fornay, editor of the Philadelphia Press, and, during the war years, Secretary of the Senate, in which capacity he met with Lincoln regularly. Fornay writes that “Lincoln had his periods of depression” and that “one evening I found him in such a mood. He was ghastly pale, the dark rings were round his caverned eyes, his hair was brushed back from his temples, and he was reading Shakespeare as I came in. “Let me read you this from Macbeth”:

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow, Creeps in this petty pace from day to day, To the last syllable of recorded time; And all our yesterdays have lighted fools The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle! Life’s but a walking shadow; a poor player, That struts and frets his hour upon the stage, And then is heard no more: it is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing.

“I cannot read it like [Edwin] Forrest,” Lincoln added, “but it comes to me tonight like a consolation.” If any American reader of Shakespeare has truly felt—through meditating on the tormented words of guilt-ridden characters like Macbeth and Claudius—the deep connection between the nation’s own primal sin of slavery and the terrible cost, both collective and personal, exacted by it, it was Lincoln.

There was another reason he might have been brooding about Macbeth on that trip to Richmond. Lincoln’s friend and self-appointed bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, recalled that “a few days” before he was assassinated, an unusually somber Lincoln had told a small group (which included his wife and Lamon) about a nightmare he had had ten days earlier, while awaiting “important dispatches from the front.” It was a dream, Lincoln said, that had “haunted” him “ever since.”

Lincoln was loath to mention this disturbing premonition to his wife, but the compulsion to share it was too great. Likening himself to a Macbeth rattled by visions, Lincoln said that “somehow the thing has got possession of me, and, like Banquo’s ghost, it will not down.” In the dream, Lincoln recalled, “I thought I left my bed and wandered downstairs.” He saw himself entering the East Room of the White House, where he was met with “a sickening surprise”: a corpse guarded by soldiers and surrounded by a throng of mourners, some “weeping pitifully.” When he asked, “Who is dead in the White House?” a soldier replied, “The President.” He “was killed by an assassin.” A “loud burst of grief” from the mourners woke Lincoln from his nightmare. The experience was so unnerving that for the rest of the night, Lincoln said, he “slept no more.” Lamon (who writes that he jotted down at the time what Lincoln said “as nearly in his own words” as he could recall), adds that Lincoln was “profoundly disturbed” by this nightmare, and continued to dwell on it: in “conversations with me he referred to it afterward, closing with this quotation from Hamlet: ‘To sleep, perchance to dream! Ay, there’s the rub,’ with a strong accent on the last three words.”

LINCOLN’S ASSASSINATION MARKED a beginning as much as an end—of Reconstruction, of the Lost Cause, of a battle for equality for the freed slaves and their descendants, and of the struggle to define the legacies of both Lincoln and Booth, in which Shakespeare, unsurprisingly, figured. Taking the hint from Booth himself, his few and scattered supporters defended the assassination on the grounds that, like Brutus, Booth had killed a tyrant. An editorial in Sign of the Times (Warsaw, Kentucky), praised Booth as a “lover of liberty, the great American Brutus . . . whose name will go down to future generations as the American Liberator—as the man who had the daring courage to destroy the first American tyrant.” The Texas Republican similarly maintained that Booth slew Lincoln “as a tyrant, and the enemy of his country.”

“Our Brutus” (a poem likely written in 1866 but that didn’t appear in print until 1913, in The Confederate Veteran) offers another example of how Booth was celebrated by his admirers as an American Brutus: “It was Liberty slain / That so maddened his brain.” It was easier to claim this heroic status for Booth, to hide behind the conspirators’ cry that “Tyranny is dead,” than to admit that Booth, a white supremacist, did what he did out of hatred for Lincoln and a deep-seated loathing of emancipation and racial equality.

Some of those who knew John Wilkes saw Shakespeare’s hand behind his act. In 1878, the theater manager John T. Ford told a journalist that “John Wilkes Booth was trained from earliest infancy to consider the almost deified assassin Brutus, just as Shakespeare immortalized him.” Ford imagined Booth thinking “‘If I failed to serve the South in my conspiracy to abduct, I can now be her Brutus.’” Booth’s mind, Ford believed, “was turned by the poetic and dramatic glamour which transmitted the story of the Roman assassination.”

Others who knew Booth shared this view, including George Alfred Townsend, a harsh critic of the South, who published the first popular book about Lincoln’s murderer in 1865. Townsend had seen Booth perform and spoke with him not long before the assassination. He too subscribed to the belief that Shakespeare was somehow behind it all, that Booth “had rolled under his tongue the sweet paragraphs of Shakespeare referring to Brutus . . . until it became his ambition . . . to stake his life upon one stroke for fame, the murder of a ruler obnoxious to the South.” Townsend also believed that Booth “burned to make his name a part of history, cried into fame by the applauses of the South,” and “that whatever minor parts might be enacted—Casca, Cassius, or what not—he was to be the dramatic Brutus.”

THIRTY-SIX YEARS AFTER the assassination, when it was safer to say such things, the Richmond playwright and businessman Edward M. Alfriend recalled that Booth had told him: “‘Of all Shakespeare’s characters, I like Brutus the best, excepting only Lear.’” Alfriend also implicated Shakespeare in the assassination. He had “no doubt” that Booth’s “study of and meditation upon those characters had much to do with shaping that mental condition which induced his murder of President Lincoln,” and “that if the truth could be known, John Wilkes Booth, in his insanity, lost his identity in the delirious fancy that he was enacting the role of ‘Brutus,’ and that Lincoln was his ‘Julius Caesar.’”

But efforts to recast the assassination of Lincoln as a reenactment of Julius Caesar found little purchase among the vast majority of Americans, even in the defeated South. The play that the nation settled on to give voice to what had happened, and define how Lincoln was to be remembered, turned out to be Macbeth. As news of the President’s murder swept through the land and Americans struggled to put their feeling into words, lines from Macbeth came immediately to mind: “O horror, horror, horror! / Tongue nor heart cannot conceive nor name thee,” wrote Benjamin Brown French, who would be responsible for planning Lincoln’s funeral, adding “We have supped full of horrors.” The same words echoed in the mind of Fanny Seward, whose father had been stabbed as part of the larger plot to eliminate the nation’s leaders, and who recorded them in her diary as well. There was even an attempt to implicate Jefferson Davis in the conspiracy to assassinate Lincoln by claiming that he quoted from Macbeth upon hearing that the President had been shot; John A. Bingham, who served as the assistant judge advocate at the trial of Booth’s co-conspirators, quoted sources in those proceedings who had heard Davis say, upon learning from a telegram that Lincoln was shot, that “If it were to be done, it were better it were well done.”

While lines from other plays were tried out, including passages from Hamlet and King John, it was Macbeth to which those mourning Lincoln found themselves turning to time and again, especially those likening him to the slain Duncan, who

Hath borne his faculties so meek, hath been So clear in his great office, that his virtues Will plead like angels, trumpet-tongued, against The deep damnation of his taking off.

These four lines were repeatedly recited in eulogies. They appeared on banners strung from storefronts. They were printed on illustrations, such as The Martyr of Liberty, in which they offer a commentary on the moment of the assassination. And they formed the centerpiece of the black-bordered funeral broadside that circulated: “Shakespeare Applied to Our National Bereavement.” The words became, as historian Richard Wightman Fox puts it in Lincoln’s Body: A Cultural History (2015), “virtually the official slogan of the mourning period.”

To mourn Lincoln as another Duncan was to move away from Booth’s violent understanding of Macbeth as much as from Lincoln’s introspective one. True, the play was about an assassination, but, unlike the one in Julius Caesar, not ideologically driven, so better suited to the story that America preferred to tell itself now that the war was over but what was to follow unclear. Some wanted to celebrate Lincoln as a radical who gave his life to free the slaves; others chose to memorialize him as a moderate who fought to save the Union, and whose death was a setback for Reconstruction and the reconciliation of North and South. Likening Lincoln to Duncan papered over the vast gap between these positions, for Duncan was something of a cipher in Macbeth. He may be the only ruler in all of Shakespeare’s works whose limitations are overlooked, one of those rare instances where Shakespeare did not build on the hints provided in his source, Holinshed’s Chronicles, where a “soft and gentle” Duncan is criticized for having been “negligent . . . in punishing offenders,” leading “many misruled persons” to “trouble the peace and quiet state of the commonwealth, by seditious commotions.” In aspiring to die like Macbeth (though not to reflect on his crime, as Macbeth himself had done), John Wilkes Booth had failed to anticipate that the man he cold-bloodedly murdered would be revered like Duncan, his faults forgotten. For a divided America, the universal currency of Shakespeare’s words offered a collective catharsis— once the story of Lincoln’s assassination was successfully recast as a national tragedy of Shakespearean dimensions—permitting a bloodsoaked nation to defer confronting once again what Booth declared had driven him to act: the conviction that America “was formed for the white not for the black man.”

This essay appears in the Berlin Journal 37 (2023-24) and is adapted from chapter four of James Shapiro’s Shakespeare in a Divided America: What His Plays Tell Us about Our Past and Future (Penguin Press, 2020). It is reprinted and published online with the author’s permission.

Image: Color print based on mechanical glass-slide by T.M. McAllister depicting John Wilkes Booth entering to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln at the April 14, 1865 production of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theater, Washington, D.C. Date ca. 1900.