Race to the Top

Shaking Up the segregated South

By Mosi Secret

The road to Virginia Episcopal School was more secluded in those days, winding a few miles from the white section of segregated Lynchburg through a wood of maple and oak to the school’s rolling campus, shielded by trees and the more distant Blue Ridge Mountains. The usual stream of cars navigated the bends on the first day of school, white families ferrying their adolescent sons. Like nearly every other elite prep school in the South, it had been the boarding school’s tradition since its founding, in 1916, that its teachers guide white boys toward its ideal of manhood— erudite, religious, resilient. But that afternoon of September 8, 1967, a taxi pulled up the long driveway carrying a black teenager, Marvin Barnard. He had journeyed across the state, 120 miles by bus, from the black side of Richmond, unaccompanied, toting a single suitcase. In all of Virginia, a state whose lawmakers had responded to the 1954 court-ordered desegregation of public schools with a strategy of declared massive resistance,” no black child had ever enrolled in a private boarding school. When Marvin stepped foot on V.E.S. ground, wearing a lightweight sports jacket, a white dress shirt, a modest necktie, and a cap like the ones the Beatles were wearing, the white idyll was over.

Marvin had just turned 14 when he arrived, and at a little over five feet tall and a hundred pounds, he was a tiny thing. His face was boyishly open, eyes and mouth big and bright, with black hair that grew in waves toward a lopsided widow’s peak. His skin was yellow-brown. Marvin had the spirit of a bouncing ball, and back home in Richmond he’d kept his classmates and teachers laughing. In all his years of schooling, he’d never earned a grade other than A. The old couple who raised him, his aunt and uncle, had given him a dime for each perfect report, but money wasn’t Marvin’s motivation. He lived to please them, and after his aunt died, when he was 12, Marvin lived to please his uncle. Going off to V.E.S. had delighted him and just about everyone else. “The neighbors and the other kids, they were just excited,” Marvin recalled. “The thing that gave me such a rush was that I could see it in their eyes. It’s like: ‘Well, you go, and you show them. You show them what you can do. You show them for us.’”

Another black boy, Bill Alexander, had also been sent that year. Bill had traveled by jet from his hometown, Nashville, to Washington and then on to Lynchburg aboard a propeller plane. He, too, was alone, though he brought more bags than Marvin, coming as he did from Nashville’s black middle class. At the airport, Bill hailed a taxi driven by a black cabby. “To Virginia Episcopal School,” Bill told him. But those were impossible words to the man’s ears. He took Bill to a black Baptist seminary instead. “I told the man, ‘No, I’m going to Virginia Episcopal School on V.E.S. Road,’” Bill told me. “He kinda looked at me. I must have said it two, three, four times before he drove all the way up to V.E.S.”

Bill and Marvin were part of a quiet but strategic experiment, funded by a private organization called the Stouffer Foundation, to instill in Southern white elites a value then broadly absent: a visceral and compelling belief in the societal benefits of integration. From the beginning, the boys were a pair, one hardly seen without the other, one name seldom said without the other to follow. Bill and Marvin. Marvin and Bill. To their white classmates and teachers, each existed as one half of a singular whole: the new black boys on campus. Bill was more reserved than his roommate (of course they would have to room together), with the look of someone holding something back, behind bespectacled eyes and a half smile. He was six months older than Marvin, seven inches taller, 35 pounds heavier, and his skin several shades darker. His face had already taken a turn toward manliness. A Presbyterian minister’s first child, Bill was preppy before he knew what preppy was. A teacher would nickname the new duo Fire and Ice: Marvin, warm-blooded, with his heart on his sleeve; Bill so confident and cool.

Bill and Marvin were part of a quiet but strategic experiment, funded by a private organization called the Stouffer Foundation, to instill in Southern white elites a value then broadly absent: a visceral and compelling belief in the societal benefits of integration.

That same fall, four other Stouffer students broke the racial barrier at Saint Andrew’s School in Boca Raton, Florida. Another three enrolled in the Asheville School in the mountains of western North Carolina. Three more went to the Westminster School on Atlanta’s affluent north side. Twenty students in all integrated seven schools, a teenage vanguard that left black America for the wealthiest white enclaves. Not all of them made it. But each year that followed, a new class came. The privately financed experiment would become a turning point in elite high school education in the South, and it would test, in very real terms, how much a black child could achieve in a white environment, and the price he would have to pay.

Black people had emerged from slavery with an almost religious zeal for education. Historians note the intense and frequent anger of the freed for having been denied literacy. “There is one sin that slavery committed against me, which I can never forgive,” wrote James Pennington, a former slave who escaped in 1828. “It robbed me of my education.” Their collective desire for learning drove the first great mass movement for state-run public education in the South. Between the 1890s and 1915, white philanthropists supported public schools and school boards for black children, ostensibly as an avenue for black advancement. But it was also an investment in subjugation. Philanthropists tended to support vocational schools for black people that prepared them for unskilled, low-wage labor, to the exclusion of the liberal-arts education that was open to white people. The very concept of elite, private high-school education was developed to provide whites an alternative to those public schools, with the effect of maintaining class divide and long-held power structures. James Dillard, a prominent educator who supported the founding of Virginia Episcopal School, was also the director of a philanthropic effort to expand schooling for black people. For white students and for his own sons, Dillard supported V.E.S.’s nurturing of mind, body and spirit. For blacks: “Three years of high school work emphasizing the arts of homemaking and farm life.”

Black leaders debated the merits of educating an elite leadership class versus more broad-based common schooling, a divide famously personified by W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Washington endorsed a more utilitarian model of education, including trade schools and workshops for industrial training. Du Bois’s approach was characterized by the term “talented tenth,” which he borrowed from a Northern philanthropist and used to describe the cadre of highly educated blacks who would lift other black people up, an ideal that grew deep roots in the culture. In 1963, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. tried to enroll his son in an all-white prep school in Atlanta but was refused. The change would have to start within the white community.

Anne Forsyth, an heiress of the North Carolina Cannon and Reynolds families, traveled in Winston-Salem’s emerging white liberal circles in the mid-1960s. One of her sons went to a Northern prep school that had long accepted black students, and Forsyth noticed that racial integration was beginning to occur almost everywhere except the prep schools of the South. An idea took hold of her. What would society look like if she exposed young wealthy white students to black scholarship students? Would the South change if its future leaders were socialized to be less bigoted? Her aim, using a few token blacks to mend the South’s racial divide from the top down, was utopian to say the least. It was also novel, a systematic effort by whites to help rid other whites of their prejudices. Providing a better life for black students was secondary.

What would society look like if she exposed young wealthy white students to black scholarship students? Would the South change if its future leaders were socialized to be less bigoted?

They wouldn’t choose just any black students. Forsyth started the Stouffer Foundation, named for her mother, and hired a small team of like-minded white colleagues who toured the South coaxing schools to open their doors to blacks and scouting black public schools for exceptional students. In the years after Brown v. Board of Education, new private schools popped up around the South, and older private schools expanded enrollment. The schools gave such reasons for their growth as “quality education,” “Christian atmosphere,” “discipline,” and “college preparation,” but mostly they were academies with nostalgia for the Jim Crow South, schools to which white families fled in order to avoid integrated public schools. Thirteen years after the Supreme Court ruling made school segregation unconstitutional, the Stouffer Foundation quietly sent off its first class.

V.E.S.’s headmaster, a New Englander named Austin Montgomery, agreed to accept Bill and Marvin over the objections of many parents and members of the school’s board. “Why, why, why have you done this cruel thing to our beloved school?” one parent wrote. “A private boarding school like V.E.S. is an extension, a part of the family,” another wrote. “We have no intention whatsoever of integrating those of another race into our family.” The school’s tract of land had been part of a working slave plantation until Emancipation.

In the years before Bill and Marvin arrived, V.E.S. tore down the remaining slave cabin on the grounds. Their dormitory bedroom looked out on Jett Hall, the campus’s main building, and from their windows the campus spread out over 160 acres, with Georgian Revival buildings cropping out of red clay and open green space. The only other black faces belonged to the hired help, like the beloved custodian, Robert Thomas, son of a man named Paul, who had worked at the school in the old days as one of the white-coated waiters who served white boys in the dining room.

Marvin and Bill each came to V.E.S. with a belief that the Civil Rights movement was his to bear, and that the way to bear it was by proving himself in the classroom. Bill, the preacher’s son, had seen the movement up close in meetings at his father’s church. Marvin’s inspiration came from black cultural figures—Muhammad Ali, Martin Luther King, and Malcolm X. “We recognized that, being the black kids, everything we did was going to be under scrutiny,” Marvin said. That meant no sneaking off campus, stealing away with girls, or missing class. “It would go beyond us as individuals, and they would say: ‘This is what all black kids do. This is what the black race would do.’ Representing yourself as an individual and then being a representative of your people—as I went through school, that became a struggle.”

Freshmen at V.E.S. were called “new boys” or, worse, “rats,” and all were subject to hazing: fetching things for upperclassmen or doing their laundry. Bill and Marvin accepted their places at the bottom of the hierarchy, assuming that status was based on seniority and not skin color, despite some of their white classmates’ reminding them otherwise. “You might hear individuals use the N-word while you’re walking down the hall, and you turn around, and nobody would say anything,” Marvin told me. “Or you may see something scribbled on the desk.”

Montgomery, the headmaster, was a near-perfect archetype of the patrician Northerner, with smart eyeglasses and an old smoking pipe always between his teeth. He kept watch over his new charges from his office window. Just weeks into their freshman year, he informed the Stouffer Foundation of a first triumph: “As I write, the two are playing touch with a dozen others out on the lovely front campus—a use to which I always like to see it put. The game goes on without regard to the usual stream of Sunday visitors and sightseers.” Calling Bill and Marvin by their last names, Montgomery wrote, “I thought you might be interested that Friday, unbeknownst to me, the freshmen held class elections, in which Alexander was chosen president by a solid majority—of which Barnard was not one!”

With uncanny speed, Bill and Marvin did just what they set out to do, rushing to the head of the class while shaking up racial allegiances, seldom losing their footing, the path they raced along hewing so closely to the one they’d imagined. A few more weeks into the school year, faculty members posted student rankings on a bulletin board, as they did at the end of every grading period. When the freshman boys pressed up against the bulletin board in their jackets and ties, they saw Bill and Marvin at the top of their class, ahead of all 40-some white boys. “I wanted to get their badges,” Marvin told me. “That became one of my mottos. I want to get what you say is good, so that you have to say I’m good.”

With uncanny speed, Bill and Marvin did just what they set out to do, rushing to the head of the class while shaking up racial allegiances, seldom losing their footing, the path they raced along hewing so closely to the one they’d imagined.

It’s possible that the stars aligned for the Stouffer Foundation’s experiment during the first months of Marvin and Bill’s time at school. “Divine intervention,” Bill calls it now. A high point came on the baseball field, where Bill attracted the attention of white boys at another school, the prestigious Woodberry Forest, which had previously refused the foundation’s request to desegregate. Forsyth, the heiress and philanthropist, later spoke about the incident: “Now, I don’t know what Bill said to these boys, but the next day during chapel, the head of student government asked Mr. Duncan”—Woodberry’s headmaster—“ if they were supposed to be leaders in the South scholastically, socially, and athletically, why weren’t they leaders in integration?” So Woodberry’s headmaster accepted three Stouffer students, the program growing by word of mouth.

On the evening of April 4, 1968, Bill and Marvin were in their dorm room when news came over the radio that Martin Luther King had been shot and killed. The movement’s leader was dead, and they were away from home. “I’m standing in the room,” Marvin recalled. “Bill is in the room. And then we hear nothing but—I mean, it’s like the whole doggone dorm was celebrating and laughing and whooping. And I looked at Bill, and I’m just like, ‘No, this is not gonna happen this way.’ I went out into the hallway, and I looked up and down the hallway, and I yelled out that if anybody thinks that this is funny, then come out of your rooms now and tell me. I wasn’t the biggest guy around or nothing like that. But they could feel I wasn’t taking no mess. And there was quiet.”

The unedited version of this article was first published on September 7, 2017, in the New York Times Magazine, as “The Way to Survive It Was to Make A’s.” To read the piece in its entirely, please visit: nytimes.com/2017/09/07/magazine/the-way-to-survive-it-was-to-make-as.html. To listen to This American Life’s complementary audio documentary of Secret’s journalism, visit: thisamericanlife.org/625/essay-b

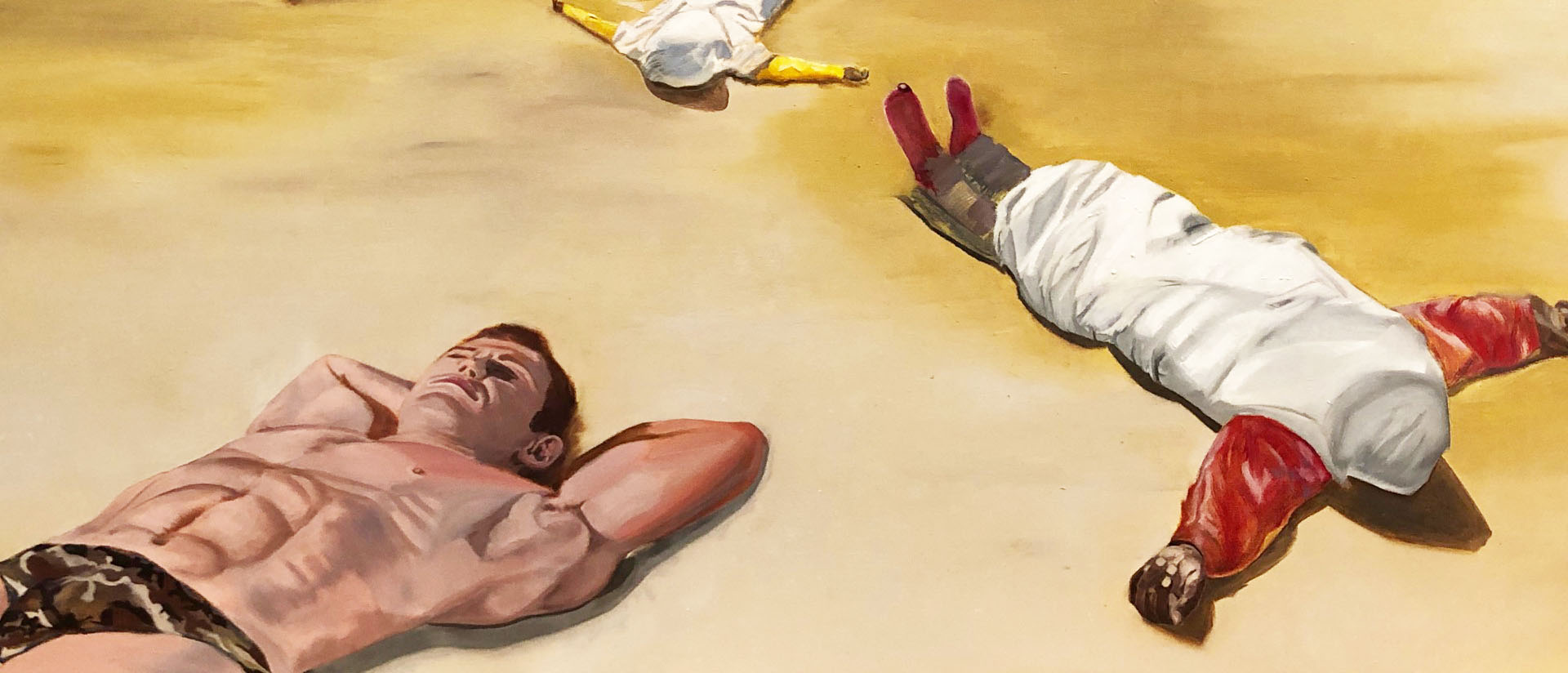

Images of Bill Alexander (L) and Marvin Barnard (R) were supplied courtesy of the author and Virginia Episcopal School