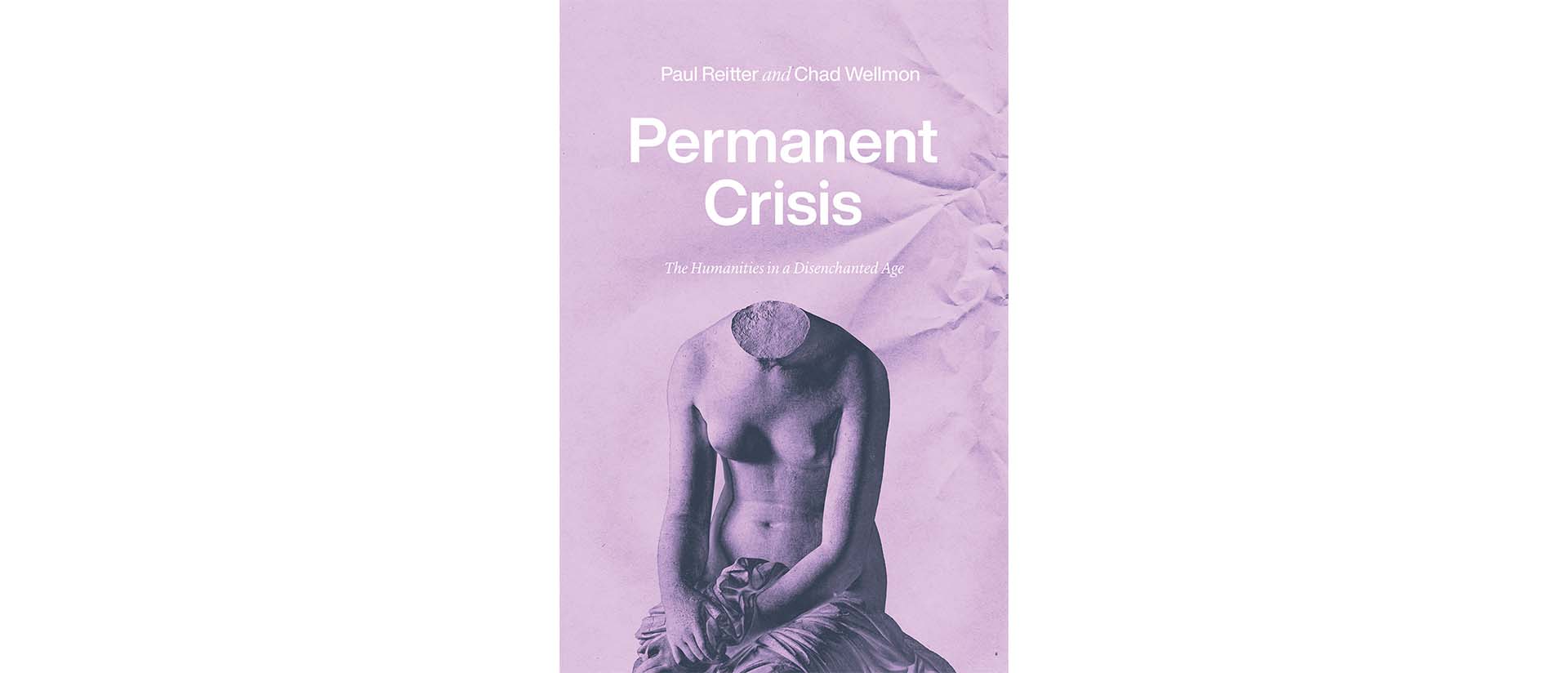

The Storm

Fiction by Lan Samantha Chang

Where is the bag of clothes from Ma’s room at the hospital?

On the shuttle at O’Hare airport, Ming frowns over James’s text. He’s en route to the east coast, more than ready to leave—frantic with the desperation that torments him whenever he’s been in Haven longer than a day or two, even and especially now that his parents are dead. Time has shifted for Ming as well as for James: reading the text, his mind circles, once again, back to December. There was the phone call to the restaurant, about the missing carpetbag. The quarrel with Katherine. The argument with O-Lan.

Why is he preoccupied by his disagreement with O-Lan, a person who, truth be told, repulses him? O-Lan smells strongly of hand lotion but underlying this is an odor lotion can’t disguise. There’s a term for this in Mandarin: “fox smell.” He has found her B.O. repugnant since their first encounter years ago, when he conversed with her in defiance of Leo’s callous disregard of this new help, ignorant, clearly without papers (which was one of the ways his father saved money). Even now, out of resistance, Ming continues to talk to her; and, as if she senses his insincerity, she makes their conversations as challenging for him as possible.

That afternoon, December 23, with James trying to eavesdrop in the dining room, she asked him whether he was still planning to fly East. She’d overheard his father telling a customer, one of the Chinese community, that he was leaving town.

“You’re flying out today?” she asked. He leaned forward to decipher her Mandarin. “You know you won’t be able to come back.”

She spoke too quickly for him. He was forced to ask, “What are you talking about?” She stared not at him, but at the artwork on the wall. She regarded the cheap Song landscape reproduction with an expression of contempt.

“There’s going to be a storm,” she said. “The storm, our storm, is moving east. And it will join with another storm, coming up the coast.”

“I’ll just have to try to go,” he said. He’s not sure of the Mandarin expression for “take off.”

She went back to her work on the counter. The kitchen was quiet in the mid-afternoon, with only a large cauldron of broth simmering on the stove.

“Hey,” he said, more harshly than he had intended.

Slowly she turned, in mocking obedience to his command.

“You told me that after I reach New York, I won’t be able to come back. What made you think I would want to come right back?”

In her impenetrable expression, he could make out the shape her face would have when she was an old woman. “I’m just saying, Young Boss, that if you decide to leave this afternoon, you won’t be able to come back. You’ll be gone for days.”

She was forcing him to ask. “What difference does that make?”

“If you were to be needed at home.”

“I have a lot of work to do. My mother is out of danger. Why would I come back?”

“You would be the one to know that. He’s your brother, Young Boss.”

This remark for some reason lit Ming up with rage, but he only answered, sardonically, in English, “Am I my brother’s keeper?”

Because she couldn’t understand, he had the last word. She turned back to chopping cabbage in a manner both servile and dismissive. Ming escaped to the dining room, only to bump into Katherine looking for Dagou and to begin that infuriating conversation. Then the phone call about the carpetbag. The meeting with James at the Other Restaurant, and then straight to the airport. Like a well-trained athlete, speeding through security and boarding, buckling his seatbelt. The flight attendant closing the door.

Because she couldn’t understand, he had the last word. She turned back to chopping cabbage in a manner both servile and dismissive.

The moment his plane left the ground, Ming knew he’d made the wrong decision. The certainty gripped him like a sudden claustrophobia. He took out his phone but couldn’t focus on the screen.

There was nothing to do. He’d have to wait it out. He adjusted his seat, closed his eyes.

But his mind wandered to the restaurant again, the conversation with O-Lan. “There’s going to be a storm.” He hated her. Her fox smell, her shovel jaw, the inexplicably familiar smirk. The minutes hobbled by. After some time mulling over this half-dream, he became aware of a change in the plane’s flight pattern: it was no longer descending, but banking. The plane had slipped into a holding pattern and was making long, sweeping circles around Newark Airport. Pushing up the window shade, he could see the distant flashing lights of two other planes looping below them, waiting. The pilot’s voice crackled over the audio system: bad weather, no one allowed to land. Air traffic control was diverting all planes inland to Bradley Airfield in Hartford, Connecticut.

An hour later he was staring at the lit grid of the Hartford runways, their edges sparkling with light snow. It was now early in the morning, and his eyes hurt. Why, after all, had he thought he could beat this storm? It was the same winter storm that had buried Haven, the snow Dagou had plowed and into which Alf had vanished. And now, on the east coast, the storm was being whipped up by a nor’easter’s howling wind.

He turned on his phone and found a text from Katherine: Big family fight at hospital.

He sat in the dark plane for perhaps five minutes with the snow-sparkled runway lights woven around him. He’d said, “I’m not my brother’s keeper!” He texted back. Thank you for letting me know.

She instantly replied, Dagou is very upset.

After a moment, he typed back, He gets that way.

He threatened your father. People heard.

As the other passengers deplaned, Ming sat belted into his seat, almost afraid that any movement would reveal something to the sender of this text. He imagined Katherine waiting, also in the dark, her black eyes fixed on her phone, her precise, smooth features reflecting its glow, a thousand miles away now. Could she look through the screen and see his agitation? He must be calm, very calm.

After a long moment, a reply came like a gift into his mind. He typed, Maybe you should talk to him. He erased it.

I’m surprised you managed to leave, she continued out of turn.

I was diverted to Hartford. He sat still for a second, then typed, I’m deplaning now.

Ming, he needs to talk to someone.

Ming could think of no way to answer her unspoken question, nothing she would accept. Finally, he wrote, You.

Wasn’t this the permission she wanted? Wanted, for whatever reason, permission to be the strong one, when his brother was weak? For a dozen years now, more mismatched every year, unwilling to let his brother go and take a chance on showing her flaws to someone who was not inferior to her? Ming scowled. And who was he, Ming, to mock her for this? Wasn’t he, Ming, also relying on her superiority and competence, leaning on her unnatural interest in his family, and on the unswerving, inexplicable bedrock of her loyalty to them all? Relying upon Katherine to get him out of a situation he couldn’t bear. The difference was that he, Ming, knew he was being a coward, while his brother was a coward without a kernel of self-awareness.

Katherine didn’t text back.

On the tarmac at Bradley Airport, hunched into the collar of his overcoat, Ming took out his phone and began to look up flights back to the Midwest. All flights were cancelled for the next two days. Air travel in the entire Northeast was at a standstill.

He would rent a car and drive to New York City. Wait out the storm there for a couple of days, dealing with an electronic blizzard of its own kind, with Phoenix. Ming chose a sport utility vehicle with four-wheel drive, a white BMW. He would blend into the snow. He felt an urgency to hide himself, to reveal his location to no one. Someone could be coming after him. This is irrational, he thought. You should go to a hotel. But he was being perfectly rational: white was neutral, white was invisible, white was innocent.

He felt an urgency to hide himself, to reveal his location to no one.

He’d opted out of all of this. Chosen to live his life away from his family. The stupidity of Dagou, the naïveté of James. The cruelty of his father. He’d done everything he could for them. Had paid dowry to the SH, given his mother what she wanted. Had tried to talk to James, to tell him to get away. Aside from coming up with bail, not to mention the fee for breaking the lease on that ridiculous penthouse, there was no way to help Dagou. He’d warned Katherine, repeatedly. Hadn’t he told her to give up? What else could have possibly done? But he’d left Katherine in Haven while Winnie was sick. (His mother would be alright, she would forgive him. She knew he needed to get away as badly as she did.) Was it possible, had Katherine been trying to tell him, that his brothers weren’t as strong as he, that his mother’s illness would be especially hard on them? Hard on Dagou? (He’d sent Katherine in his place. He’d left town. Katherine knew he had done this.)

He drove over the metal teeth at the rental exit, steering the BMWthrough a flurry of snow toward Highway 91. He would turn south, toward the city.

But when he reached the highway his hand shot out and flicked the signal to the left, toward the north. He stared at the blinking arrow and thought of O-Lan’s little triangular teeth, like a cat’s teeth. He must follow it, the blinker heading not south, toward New York City, but north, into Massachusetts, where he would reach the interstate that would lead him back to Haven.

There had been a maddening superiority about the corners of O-Lan’s mouth. But despite her warning to him that he wouldn’t be able to return, he was coming. As for Katherine, who’d called him up for the sole purpose of chastising him for leaving Haven, leaving his brother: he would show Katherine; he would arrive after traveling heroically through the night, and she would be astonished, humbled.

Gradually the snow grew pale; the sun had risen. He hadn’t yet reached Rochester. It was the morning of Christmas Eve; Dagou would be preparing for the party.

All day, Ming drove on, stopping for coffee and catnaps in the passenger seat. As he had guessed, the snow gave out near Erie, Pennsylvania; the highways in Ohio were well plowed. At 3 a.m. on Christmas Day, the sky was clear. He went into a service plaza to stretch his legs. Holding a fresh, black coffee, he walked past a man and a boy wearing puffy down jackets. The boy was sleepy but the man and Ming locked eyes for a moment. The man’s eyes popped open. Startled, Ming checked his reflection in the window. An alien and yet familiar creature stared back at him from the semi darkness. Its face was that of a stranger: sallow, greenish yellow skin, slits for eyes. The creature was unshaven, his dark mug protruding. Ming raised his arm; the creature raised its arm. He hurled his coffee and a blotch covered the window. The smell of coffee hit the air. Hot dark drops splattered on his shirt.

“Hey!” somebody yelled.

He bolted through the doors and out into the snow, ran to his car, and raced back to the highway.

It was afternoon on Christmas Day before he turned on his phone and found several voice messages from Katherine, Please call. It was from Katherine that Ming learned his father had died in the cold.

This story is excerpted from Lan Samantha Chang’s forthcoming novel The Family Chao, to be published by W. W. Norton & Company in February 2022. It is published here with permission of the author and The Wylie Agency (UK), Ltd.