Diminuendo Lagrimoso

Tracing the decline of big opera voices

By Andrew Moravcsik

Whether one overhears standing- room queue conversations, reads opera critics in the newspaper, or seeks recommendations for recordings, one is struck by the widespread perception that opera is in decline.

Not all opera, of course. The singing of Baroque and contemporary operas, and even those of Mozart or Rossini, remains healthy. Provocative stagings abound. State subsidies, private funding, and the move to watching live operas remotely on video create a workable financial basis. Training has improved, assuring that the average performance even at obscure opera houses is minimally competent—something not true a century ago.

Yet at the heart of the opera world, decline is evident. I am referring to the inability to find singers to cast the mature works of Verdi and Wagner, as well as Puccini, Strauss, and others. These operas require what opera connoisseurs call “spinto” and “dramatic” voices. These are the most powerful, expressive and weighty voices in opera, able to project over a massive orchestra for three to six hours at a stretch, while maintaining the sharp edge, dark resonance, and precise diction that convey bold and direct emotions. Over 40 percent of opera performances every year worldwide require them, including for such repertoire classics as Aida, Il trovatore, Die Walküre, and Tristan und Isolde. The sad truth is that the very best opera houses today are unable to cast these works with superstar voices. Singing is certainly competent, but the heights do not approach those widespread fifty years ago and well-documented on recordings.

At the heart of the opera world, decline is evident. I am referring to the inability to find singers to cast the mature works of Verdi and Wagner, as well as Puccini, Strauss, and others.

Conductors and administrators sound the alarm. Riccardo Muti observes: “We have a lot of singers good for Mozart and Rossini, but singers in the heavy repertory are becoming fewer. . . . It’s certainly impossible to cast an opera like La forza del destino well.” The late James Levine recalled the “sensationally full-scale” singers he worked with a generation earlier: “In any given Met season now, it’s unlikely we could play Don Carlo, La forza del destino, Un ballo in maschera, and Aida. We just don’t have the same density of that kind of singer now.” One American impresario adds: “We all know that no one today can sing better than a B-plus Rigoletto.” The same goes for Wagner. Soprano Nina Stemme, among today’s finest Brünnhildes, echoes many in the business: “Unfortunately we must recognize that Flagstad and Melchior really ruined everything for subsequent Wagner singers. No one today comes close.”

For the last decade, I have headed a team of researchers, based at Princeton University, conducting the first academic study ever to attempt to measure operatic quality and conduct systematic scholarly research in this area. Does this decline in world-class superstars really exist? If so, what has caused it and what can we do about it? Though much commentary and considerable debate exists regarding which singers are the greatest, no researcher has ever sought to measure and track the quality of operatic singing systematically over time. We do so in two ways: conducting confidential interviews with opera professionals and analyzing reviews of every extant recording of an opera. Both reveal a marked decline in spinto and dramatic singing.

So far we have conducted wide-ranging confidential interviews in nine countries with over 150 opera professionals: impresarios, conductors, coaches, casting directors, critics, scholars, consultants, singers, accompanists, agents, and teachers. Among many questions, we ask them whether they perceived any recent changes in the very best spinto and dramatic singing. Over 95 percent spontaneously volunteer that a significant decline had occurred. Almost all date it to the 1960s and ’70s. They single out Verdi as the area of greatest crisis, though Wagner has suffered as well. Moreover, whereas the average singer is better trained, the peaks of exceptionally great singers are disappearing. In sum, as one top consultant put it to me while sitting at a café in Munich, “When a top company asks me to suggest singers for Aida, my first response is simply to tell them: ‘Just don’t do it!’”

Whereas the average singer is better trained, the peaks of exceptionally great singers are disappearing.

We also compiled and analyzed a dataset comprising reviews of every extant audio and video recording (since 1927) of any part of two operas each by Verdi (Il trovatore and Aida) and Wagner (Tristan und Isolde and Die Walküre). These data confirm precisely what industry insiders report: the quality of the best Verdi singing has dropped markedly, and Wagner slightly less, since the 1960s. Are such complaints just self-indulgent nostalgia—the grumbling of opera lovers overly attached to youthful memories, scratchy recordings, and aging divas? To exclude such “nostalgia bias,” we also asked interview subjects and examined reviews about the quality of Baroque, Mozart, and bel canto opera, as well as conducting, orchestral playing, and staging. Respondents and critics uniformly agree that the quality of all these things has remained stable or improved—suggesting that the results are not driven by generic cultural or perceptual bias, like nostalgia, or any other such measurement error. The decline seems real.

But what explains this decline? And why do we not see it with regard to other types of opera or instrumental classical music? Opera insiders, who are well aware what is happening, offer many speculations. Many focus on self-interested or ill-informed behavior by some sub-group in the opera business. Yet most lack logical coherence and empirical support.

Some blame teachers and coaches. Contemporary university and conservatory teachers, it is said, lack real-world operatic experience. Yet, historically, most successful teachers have never been retired singers. Moreover, is implausible that highly professional institutions staffed by teachers who are successfully training young singers to handle fiendishly difficult Baroque, Mozart, bel canto, and modern repertoire are inexplicably incapable of teaching them to sing Verdi and Wagner. Finally, if training is poor, why would the average level of performance be rising, even as the number of great singers has declined?

Many criticize myopic, musically illiterate, and money-grubbing agents, managers, and opera administrators. Supposedly they tempt singers to sing too much, to attempt big roles too early in their careers, and to jet around the world, thereby ruining their voices before they achieve maturity. Yet our research shows that the average singer tackles big roles later and performs less often than fifty or a hundred years ago, while the modern health risks are, overall, lower.

Others condemn modern acoustics. Many professionals believe that higher orchestral pitch, larger opera houses, and louder orchestral playing place singers under intolerable acoustical stress. Yet since 1970, orchestral pitch has actually dropped from A448 Hz or more in some places down to A440– 443 almost everywhere, while almost all the top houses remain the same ones as existed a half century ago, including venerable theatres in Berlin, Munich, Vienna, Bayreuth, New York, and Milan. While louder orchestras may inhibit singers, the great increase in instrumental volume occurred early, not late in the twentieth century— and, in any case, should not affect recordings.

Many professionals believe that higher orchestral pitch, larger opera houses, and louder orchestral playing place singers under intolerable acoustical stress. Yet since 1970, orchestral pitch has actually dropped from A448 Hz or more in some places down to A440 – 443 almost everywhere.

Still others point to changes in taste, most often the fashionable rise of Baroque and modern opera. Yet the fact that early and contemporary music are “in” doesn’t necessarily mean that Verdi and Wagner are “out”—any more than better violin playing implies worse cello playing. About half of operas performed worldwide still call for spinto and dramatic voices.

Finally, some blame underlying cultural and economic trends. Perhaps classical singing has become less fashionable and profitable, which discourages young people from taking it up. Surely this is not the whole story. Unlike their predecessors, contemporary singers receive subsidized training and earn more (both in real terms and as a percentage of the median wage) than in decades past— right up to Andrea Bocelli, today worth tens of millions. And while opera is admittedly less fashionable than pop music, the extraordinary quality of less glamorous and remunerative types of classical music—such as symphonic playing, string quartets and Baroque singing—suggest glamour and money cannot be the decisive obstacles.

It is more plausible to explain the creation of great musicians as an activity deeply embedded in the broader society and culture. As the saying goes, “It takes a village to raise a child.” Cultivating great opera singers— like great instrumentalists, artists, athletes, and researchers—requires effective social institutions that can perform three critical functions: identify talented individuals, train them for the extended period to maturity, and then give them an opportunity to practice their vocation. Each step is essential. Decline begins if such institutions atrophy, which is what we have observed over the past fifty years.

It is more plausible to explain the creation of great musicians as an activity deeply embedded in the broader society and culture.

The causal chain starts with the identification of young individuals with talent. Most specialized artistic, athletic, and intellectual activities require rare levels of natural ability, passion, and commitment. Finding such individuals is possible only through inclusionary social institutions able to scan the youth population for such potential and to provide sufficiently intense training to confirm its existence. Second, social institutions must encourage gifted individuals to remain committed to further rigorous training until they reach professional maturity. No matter how much talent one has, someone with neither experience nor instruction has next to no chance to embark on the road to a high-level professional vocal career as an adult. Third, the few who emerge as mature and trained individuals must be offered attractive and demanding professional opportunities. After decades of work, if no career options exist, or if society declines to employ the skills of talented and trained individuals, they are unlikely to enter the profession in the first place or to remain in it as adults.

To illustrate how all three institutional functions can work well, consider basketball. The most global of all sports today, it has witnessed an extraordinary improvement in play over the past half century. The foundation of this success has been the development of increasingly universal social institutions to identify, train and employ talent. Almost anywhere on the globe, a tall and fit young person will have a basketball thrust into his (and, increasingly, her) hands. Schools, universities, clubs, associations, family, friends, and even the government will offer encouragement and training, especially in countries with tall populations and a long basketball tradition. Should individuals succeed, they will then be incentivized to play basketball until they prove that they are unable or unwilling to reach the pinnacle: the National Basketball Association (NBA). And, if they make it, the NBA welcomes them, regardless of background. Since 1950, the number of African Americans has risen from zero to over 70 percent, and since 1995, the number of international players has risen from only 5 percent to 25 percent—with the last five annual Most Valuable Player awards going to non-Americans. Today, this global basketball infrastructure harvests the talent of the entire planet.

Basketball is hardly unique. The wealth, health, diversity, and global links of modern societies allows them to cultivate ever greater excellence across most athletic, artistic, and intellectual activities. Even unfashionable and unpopular sports, or dowdy and obscure areas of classical music—such as the performance of string quartets or contemporary atonal music— spawn effective infrastructures to attract and exploit human potential.

Yet this system has broken down in the creation of spinto and dramatic opera singers. Today each of the three steps is dysfunctional.

First, consider institutions to identify young operatic talent. A century ago, singing was a nearly universal social activity in (Western) churches, schools, clubs, homes, theaters, and concert halls. Everyone in a community knew who could sing loudly, sweetly, and on pitch. Since the middle of the twentieth century, however, declining church attendance, shifting educational priorities, and the atrophy of live music (in favor of recorded music) have meant that fewer people sing in public at an early age, if ever. Moreover, as church choirs, youth choruses, Broadway shows, folk and rock music, and public oratory have all “gone electric,” those who do sing are unlikely to perform without a microphone—and, therefore, have developed different skills. The non-amplified voice, produced quite differently, has been relegated to the cultural margins, whereas the fully trained classical voice has become an oddity. The narrowing talent pool affects spinto and dramatic opera singers more than any others, because they have always been the rarest. And those among them who are rarest of all—heavy low voices like contraltos and dark basses—are now close to extinct. In sum, most who possess a genuinely “operatic” voice today never find out.

Second, spinto and dramatic singers today find it challenging to remain in the profession and receive training to professional maturity. A century ago, in a world of lower incomes and persistent inequality, music was an exceptionally meritocratic vocation in which a lower-class person would persevere—even if it were a long shot. Today, spending one or two decades to become an opera singer seems a relatively risky proposition when comfortable white-collar jobs for educated individuals abound. Managing the transition has become doubly difficult as vocal style has followed technology, widening the stylistic distance between pop and classical singing and thus making it far more difficult to “cross over” from popular to classical music.

Today, spending one or two decades to become an opera singer seems a relatively risky proposition when comfortable white-collar jobs for educated individuals abound.

Coping with this transitional period impacts spinto and dramatic singers disproportionately, simply because for them it is longer. World-class instrumentalists often emerge as child or teenage prodigies, while Baroque, Mozart, modern, and even bel canto opera singers often mature in their early or mid-twenties. For them, family support, formal music training, and opera apprentice studios suffice to tide them over. Yet spinto and dramatic singers are nearly unique among athletes and artists in that they typically do not mature until they are in their mid- to late thirties. Not atypical is the early twentieth century Norwegian soprano Kirsten Flagstad—whom most critics consider the greatest Wagnerian soprano ever recorded. She sang lighter fare in provincial Oslo until she was near 40, never suspecting she would become capable of singing Wagner, then emerged overnight as a global superstar. Even those lucky few who establish themselves as successful Mozart, bel canto, or Baroque stylists in younger life—a path ever more challenging anyway with the advent of a lighter, specialized approach to “early music”—struggle to make the transition.

Third, opera houses today hesitate to cast some of the best spinto and dramatic singers, even when they are available, because appearance trumps voice. In casting, the power of directors and stage designers has grown; that of conductors and music directors has shrunk. While this is probably the least important factor, singers are increasingly hired as much on looks as on voice—not least in German-speaking countries. Top conservatories now admit 18-year-olds not simply on vocal ability but also on “charisma”—a politically correct codeword for being good-looking and not too heavy. (One long-time admissions officer at a top institution shrugged it off: “Above all, it’s my responsibility to make sure that our graduates work.”) Younger artists complain of always having to be “HD ready,” and of “fat-shaming” by critics and colleagues. Everyone wants to avoid the fate of the soprano Deborah Voigt, who was fired from the title role in the 2004 Royal Opera House production of Ariadne auf Naxos because she could not fit into the stage director’s favored little black dress. Voigt responded by having surgery to lose weight, which some observers feel permanently damaged her voice. Again, this trend affects spinto and dramatic singers disproportionately, because, as the legendary mezzo Marilyn Horne put it, “Big voices come out of big bodies.”

Opera houses today hesitate to cast some of the best spinto and dramatic singers, even when they are available, because appearance trumps voice. In casting, the power of directors and stage designers has grown; that of conductors and music directors has shrunk.

To illustrate what happens when all three steps on the road to excellence go wrong, consider the case of Italy. The birthplace of opera and long the major singer-producing country of Europe, Italy today produces hardly any major spinto or dramatic singers. The reasons lie deep in Italian society. In the late nineteenth century, Caruso, a child of the Neapolitan ghetto, received a scholarship to a private school specializing in choral singing, sang conservatory-level performances in church, busked on the streets of Naples, received years of lessons on credit, avoided military service because he was a singer, and endured nearly a decade as an impoverished itinerant singer working his way up in small houses. A half-century later and three hundred miles north, in Modena, Luciano Pavarotti sang solos in church (like his father), toured Europe with an award-winning city choir, and spent nearly a decade in unpromising training. Both became the most famous tenors of their times, despite lacking good looks.

By contrast, in Italy today less than 20 percent of the population attend mass, post-Vatican II churches make little use of classical singers, recorded pop has replaced busking, schools are chronically underfunded, the number of opera houses has dropped, and singers need to look their parts. Had Caruso and Pavarotti been born within the last half-century, it is unlikely we would have ever heard of them.

The deeply sociological nature of this tripartite explanation of why spinto and dramatic singers are scarce today implies that the decline cannot easily be reversed. Returning to a world in which schools, churches, and choirs teach young people to sing without microphones, creating decades of full and meaningful employment for emerging singers, and transforming our culture so that appearance no longer matters are quixotic aspirations. Still, smaller steps may be worth a try: allowing younger singers to perform Verdi and Wagner, mounting performances in smaller houses, employing acoustically resonant sets, providing “affirmative action” for large-voiced singers, and recruiting more talent from the developing world.

Such reforms are imperative because the future of opera depends on their success. The works of Verdi, Wagner, Puccini, Strauss, and others that require these endangered great big voices capture the popular imagination like few others. They fill houses and introduce new listeners to the art form, cross-subsidizing more adventuresome programming. If spinto and dramatic singing is not reimagined, reorganized, and revived, opera itself may not survive the twenty-first century.

This article first appeared in the Berlin Journal 37 (2023-24).

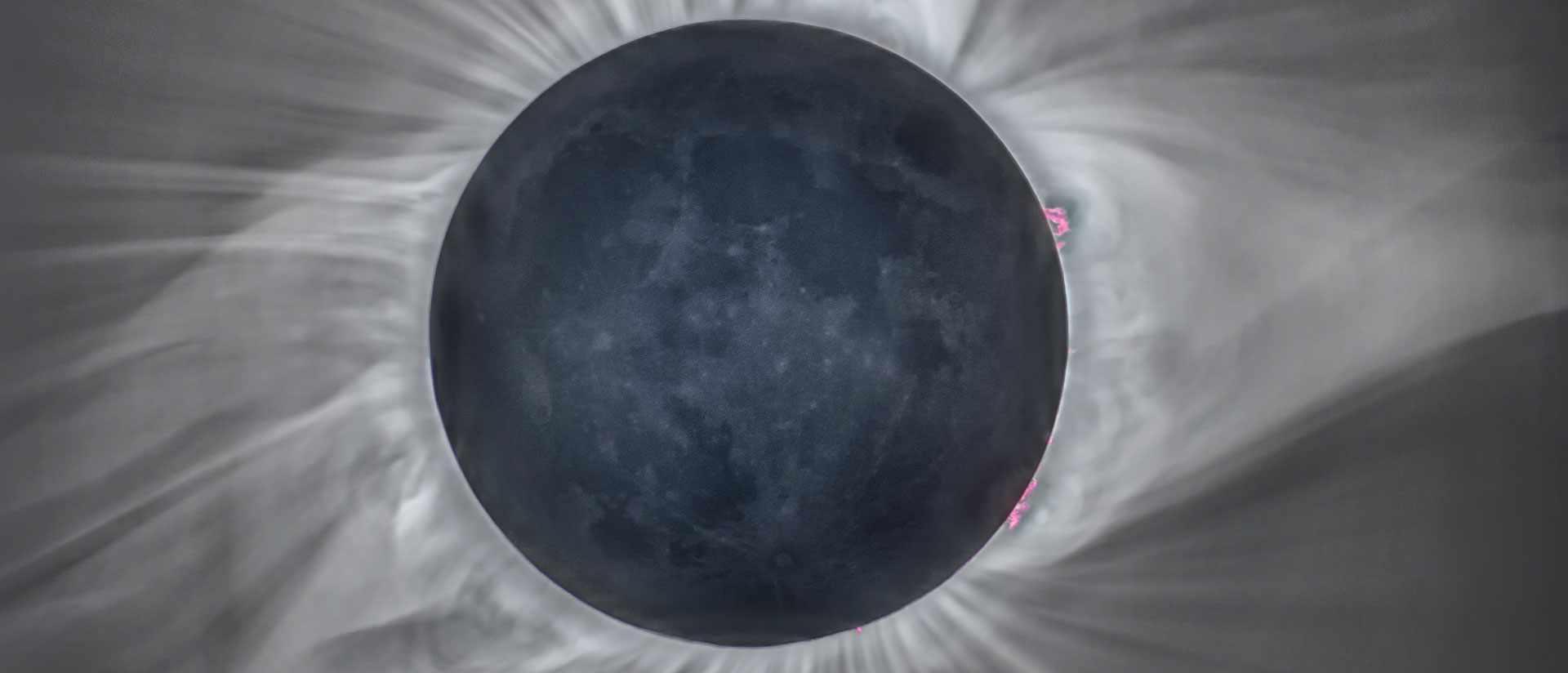

Photo: The 1983 Metropolitan Opera Gala, featuring legendary spinto and dramatic singers including Monserrat Caballé, Birgit Nilsson, Jessye Norman, Leontyne Price, Grace Bumbry, Marilyn Horne, Plácido Domingo, José Carreras, Luciano Pavarotti, Renato Bruson, Nicolai Ghiaurov, Sesto Bruscantini, Thomas Stewart, and James Morris. Photo: James Heffernan / © Metropolitan Opera