To Make a King

Rebellion, legitimacy, and the Visigothic quest for order after Rome

by Damián Fernández

Outside specialist circles, the centuries that followed the so-called fall of the Roman Empire in the western Mediterranean are still known as the “Dark Ages,” despite heroic efforts to rehabilitate the period over the past half century. To a certain extent, early modern prejudices are responsible for tainting this era with gloom, and its sense of obscurity is reflected by the limited number of texts that have survived from the period. Still, overcoming these misconceptions yields access to the rich history of a time that has been so often distorted in the service of nationalist or religious agendas. This is particularly true for the Visigothic Kingdom of Toledo, the post-Roman polity that ruled over the Iberian Peninsula and a small strip of southern France from the mid-sixth century until the Arab-Berber conquest, in the early eighth century.

The Visigoths were a confederacy of different ethnic groups that had coalesced around the leadership of a Gothic warlord elite by the fourth century in the lower Danube region, in Eastern Europe. They fought against but also on behalf of the Romans. After settling in Roman Aquitaine (present-day southwest France), in 418, they carved a polity within the fissures of the crumbling empire. Defeated by the Franks in 507, Visigothic elites joined with the descendants of the Roman ruling classes to build a kingdom that lasted nearly two centuries, until the Islamic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, in 711. The distinction between Romans and Visigoths thus rapidly disappeared, since by the sixth century little beyond family memory separated them. As a result, by the seventh century, “Roman” primarily referred to the eastern Roman empire (today known as the Byzantine Empire) rather than an ethnic category that excluded Visigoth descendants. The Visigothic kingdom, as such, like the other so-called successor states, illustrates how societies navigated the complexity of ethnic identities in a world that was in many ways still “Roman” but had to adapt to new political frameworks.

But the Visigoths and (eastern) Romans still differed in a few ways. For one, emperors ruled over the Roman empire from Constantinople, but kings ruled locally over the Visigothic polity. Visigothic kingship was also different from that other main post-imperial polity, the Frankish kingdoms. The Franks were a confederacy of Germanic-speaking peoples who had taken control of present-day northern France, Belgium, Netherlands, and western Germany amid the crumbling Roman Empire. By the sixth century, they were ruled by the members of one family, the Merovingians. They followed principles of succession, which included partitioning the kingdom among the heirs of the deceased ruler. The Visigoths, on the contrary, had few rules of succession—neither birth nor election guaranteed access to the throne. Co-rulership was possible (among father and son, for example), but partition was less common. While kings did occasionally inherit the throne from their fathers or were chosen by a council of bishops and magnates, more often they acceded to power as a result of palace intrigues, silent coups, or violent revolts and rebellions.

Despite the overall documentary dearth of the period, we are relatively well informed about these rebellions, usurpations, and coups, thanks to an unusually wide array of sources. One is the only piece of narrative history that survives from the period, the History of King Wamba, about a revolt crushed by the king in 673. Chronicles, the other main historical genre, include a series of short entries about numerous coups and rebellions. Other sources are records of Church councils, which could issue ecclesiastical sanctions against those who broke oaths of loyalty to the king, and served as negotiation arenas for kings with dubious legitimacy. Written Visigothic laws evidence punishments meted out upon rebels and oath-breakers. Even hagiographies—religiously inflected accounts of the lives of saints—could not avoid mentioning conspiracies and rebellions, offering valuable clues to historians. All in all, Visigothic authors seem to have been keenly interested in—or simply unable to ignore—the figures of rebels and usurpers, evidencing that state-building after Rome was not only a matter of military conquest, it was also an arduous process of defining the contours of political legitimacy.

Visigothic authors seem to have been keenly interested in—or simply unable to ignore—the figures of rebels and usurpers.

Why did contemporaries perceive rebellion and usurpation as a critical problem? Because no less than half of the kings of the sixth and seventh centuries were overthrown, a tally that does not include rebels who actually failed. The Visigoths’ quarrelsome political culture was a frequent theme both for Hispanian authors and for writers from other kingdoms, who pondered its harmful effects on the kingdom’s life. Writing from the nearby Merovingian kingdom in the late sixth century, the bishop Gregory of Tours claimed that the Goths had adopted the abominable practice of killing kings they did not like. The Burgundian chronicler Fredegar echoed this opinion, describing the Visigoths’ presumptive habit of killing their kings as “the disease of the Goths.” Back in the Visigothic kingdom, Bishop Isidore of Seville deplored that the Goths were destroying themselves through the mutual devastation of civil wars, even though they were aware of the danger. In sum, intellectuals of the age characterized Visigothic politics as perennial rebellions with pernicious effects on society.

When talking about political insurgence, intellectuals and royal propagandists in the Visigothic kingdom had at their disposal a rich literary tradition inherited from the Roman empire. Despite the political vicissitudes of the fifth century, when the empire disintegrated in the West, Roman elite culture and idioms of power carried over to the cultural landscape of the newly crafted kingdoms. When they considered a king illegitimate, Visigothic writers referred to the ancient figure of the Roman usurper, calling him tyrannus: a “tyrant.” Classical authors also described tyrants as violent, greedy, and enslaved to their impulses. Visigothic literature often echoed descriptions of these moral failings, sometimes also portraying tyrants as undermining social hierarchies. Thus the Late Roman tradition of “usurpation” describes both the illegitimate ruler and the morally flawed leader—a distinction sometimes articulated as “tyrant by origin” and “tyrant by exercise.” Both the rebel and the tyrant, according to this view, stood in opposition to the ideal king.

Though all post-imperial kingdoms were deeply rooted in Roman traditions, the political, religious, and literary portrayals of rebels/usurpers changed over the course of the centuries that followed Rome’s demise. Visigothic intellectuals and political elites, for example, did not simply receive Roman ideas; they actively transformed them to address the concerns of the day. Some authors began to portray rebels as foreign invaders. One contemporary chronicler, John of Biclarum, narrated the conquests of King Leovigild in the 560s–580s, offering insights into the reign of a king who is considered the “state builder” of the Visigothic kingdom. Most of Leovigild’s “conquests” targeted cities and territories under his nominal rule that had rebelled against his ambitions to build a stronger monarchy. Summarizing the impact of these campaigns, John of Biclarum noted that “with tyrants destroyed on all sides and the invaders of Hispania overcome, King Leovigild had peace to reside with his own people.”

Though all post-imperial kingdoms were deeply rooted in Roman traditions, the political, religious, and literary portrayals of rebels/usurpers changed over the course of the centuries that followed Rome’s demise.

This connection between rebellion and invasion further tightened in the seventh century, to the extent that the two gradually became almost synonymous. Writing a generation later, Isidore of Seville described one successful domestic revolt in similar terms: “Witteric had invaded [the kingdom] while [Liuva] was still alive.” In the second half of the seventh century, a law passed by King Wamba introduced penalties for those who failed to provide military aid to the king during an invasion or a revolt, treating these threats equally. These and many other examples illustrate the growing connection between rebellion and invasion in Visigothic political thought. A rebel was not only a person who wished to access the throne illegitimately; he was, through his actions, an alien to the polity he wished to rule.

There is another influence to consider: Christianity. Late-Roman Christian authors intervened in polemics that directly or indirectly addressed the relationship between the Christian god and the emperors—and thus the portrayal of rebels. Though this Christian discourse affected Visigothic political only late in the kingdom’s history, it is possible to trace the formation of a religious discourse about the figure of the “rebel as sinner” throughout the seventh century. According to a council of bishops in 633, rebellion implied breaking a sacred oath, and thus led to excommunication. A council three years later declared that supporting an illegitimate contender to the throne was equivalent to superstitio or paganism and therefore, again, deserving of excommunication.

In the second half of the seventh century, the idea of the rebel-sinner really gained momentum, particularly under the pen of Julian of Toledo, an influential bishop who pursued a determinedly religious agenda of anti-Jewish polemic, cult reform, and doctrinal unity within the Visigothic Church in the 680s. In his history of a rebellion against Wamba, he referred to the corrupting power of the rebel, whom he describes as leading others into sin. Leaving no room for doubt, Julian went so far as to argue that the Devil himself was responsible for the impulse to rebel. Julian’s influence was felt even after his death. When his successor conspired against King Egica, in a failed coup, the king urged a council of bishops to help him uproot the evils that threatened the kingdom, including rebellion, which he placed alongside other targets of Visigothic ecclesiastical ire: homosexuality, Judaism, and idolatry. Rebellion, in the view of Egica’s ideologues, was part of a continuum of mortal sins that threatened the purity of the kingdom and endangered the salvific mission of king and bishops.

By the early eighth century, the three characterizations of rebels—as tyrants, invaders, and sinners—were common intellectual currency, but their deployment did nothing to effect greater political stability.

When Visigothic authors discussed rebellion, they were actually thinking about something much larger: kingship and the creation of a polity. In 653, in a much-discussed quote, King Recceswinth (himself the son of a former rebel and successful usurper) proclaimed before a council of bishops that “laws, not the person, make a king,” stressing the legal basis of royal legitimacy. In the preceding decades, political and ecclesiastical elites had finally elaborated rules of accession, which included an election by a council of bishops and grandees. These rules were rarely followed, but they do reveal the political class’s attempt to ground legitimacy within the law. So important did the “legitimacy of origin” become, that usurper kings sought to bolster their accession with an ex post facto conciliar agreement—in practice, bishops who gathered to refer to the king as the legitimate ruler in their conciliar acts. Legitimate rituals and procedures, some Visigothic authors claimed, were not simply procedural trivialities, but a sign of a prosperous reign. By the late seventh century, the History of King Wamba interpreted the king’s military victories against his enemies as a consequence of his respect for the rituals and procedures of accession.

So important did the “legitimacy of origin” become, that usurper kings sought to bolster their accession with an ex post facto conciliar agreement—in practice, bishops who gathered to refer to the king as the legitimate ruler in their conciliar acts.

Law and ceremonial practice were not the only sources of growing royal legitimacy. By the seventh century, Iberian authors portrayed the Visigoths as a people destined for a special historical role, with superior martial and moral virtues. The standard formula to describe what we would today call the “state” or the “nation” was “the king, the people, and the fatherland of the Goths,” which gave a territorial and ethnic expression to the Visigothic polity. Moreover, seventh-century rituals of authority involved sacred oaths of loyalty to the monarchy as well as the ceremony of the king’s anointment, inspired by the Old Testament. The king had, in effect, become the ultimate guardian of the Christian salvation of his subjects.

It is important to note that Visigothic elites were not entirely genuine in respecting their kings. They knew their rulers could themselves be usurpers, militarily and judicially intrusive (especially against elite interests), of questionable morals, and not particularly pious. Some Visigothic authors even found an explanation for these kinds of kings, claiming they were sent by God to punish the sins of their people. As such, their careful discourses on rebellion not only reflected the character of an individual rebel, they were also, and above all, rhetorical tools of political and social domination. As such, they reveal how Visigothic elites conceived of their community, and their efforts to convey authority in a society that needed to be persuaded into compliance. Their narratives of rebellion strengthened economic, social, and religious modes of domination, and also provided justification for state intervention to support these hierarchies. Visigothic elites inserted the figure of the rebel into a landscape of unrest that included runaway slaves, perjurers, bishops who committed abuse against the clergy, hostile enemies from foreign kingdoms, or forcibly converted Jews who maintained their beliefs. These groups were described with the same terminology Visigothic literature employed for rebels.

Visigothic rebellions and the way they were incorporated into Visigothic political discourse illustrate the multiple dimensions of state-building after Rome and the centrality of the monarchy in Visigothic political tradition. The king was to be the enforcer of an orderly world that would secure prosperity at all levels—but particularly among those already at the top of social hierarchies. The rebel was not necessarily the counterpart of the king; he was something much more useful: the ever-deployable foil to an ideal political community that intellectual and political elites envisioned—and aimed to construct—in the aftermath of empire.

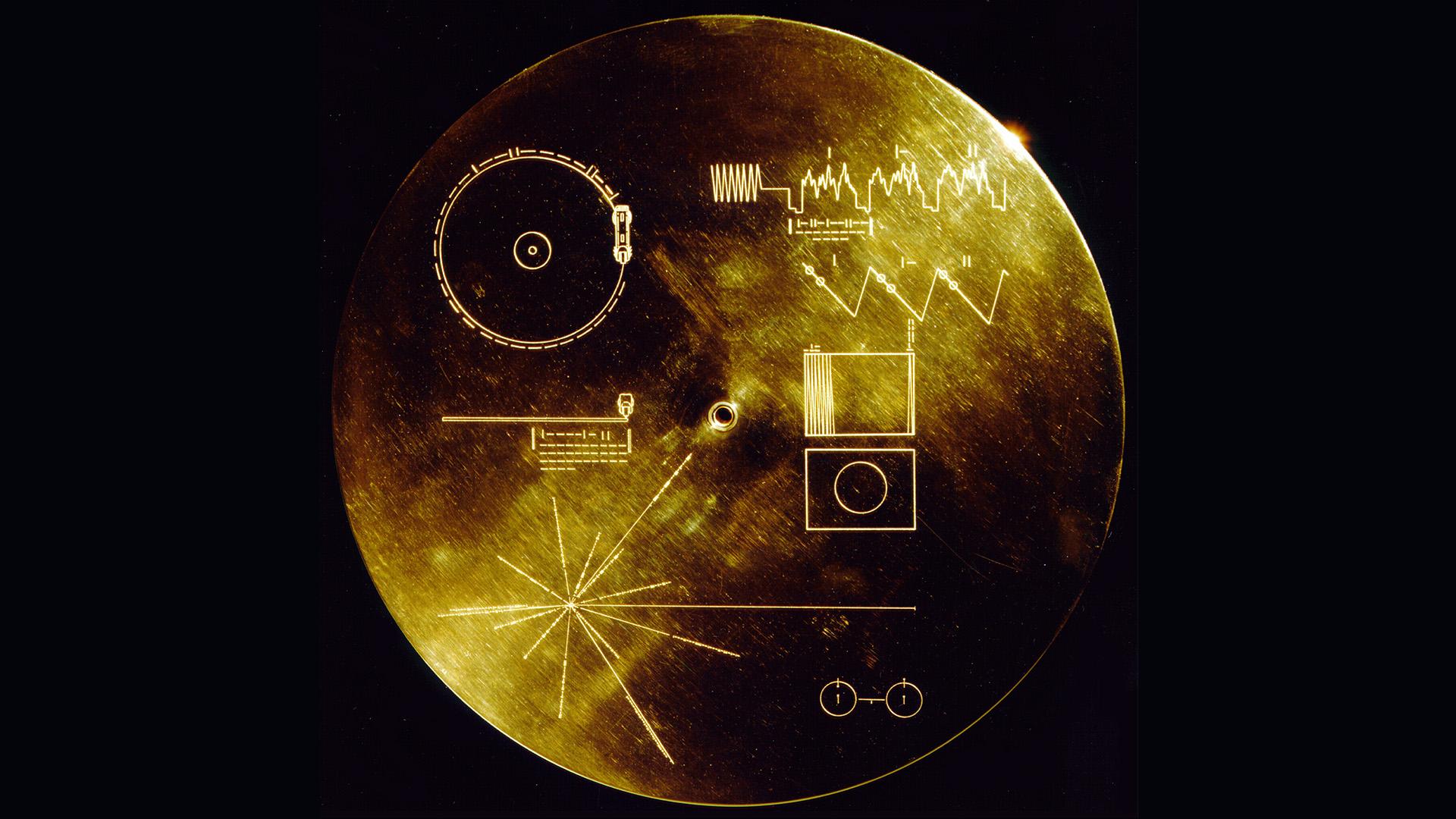

Photo: Detail from the Codex Vigilanus, Spain, 976 CE, showing three early Visigoth Kings of Hispania (L–R), Chindaswinth (642–653), Recceswinth (649–672), and Egica (687–702). Courtesy Real Biblioteca del Monasterio de El Escorial, Madrid. Copyright: bpk