Capped

Taxing and regulating carbon use

By George T. Frampton

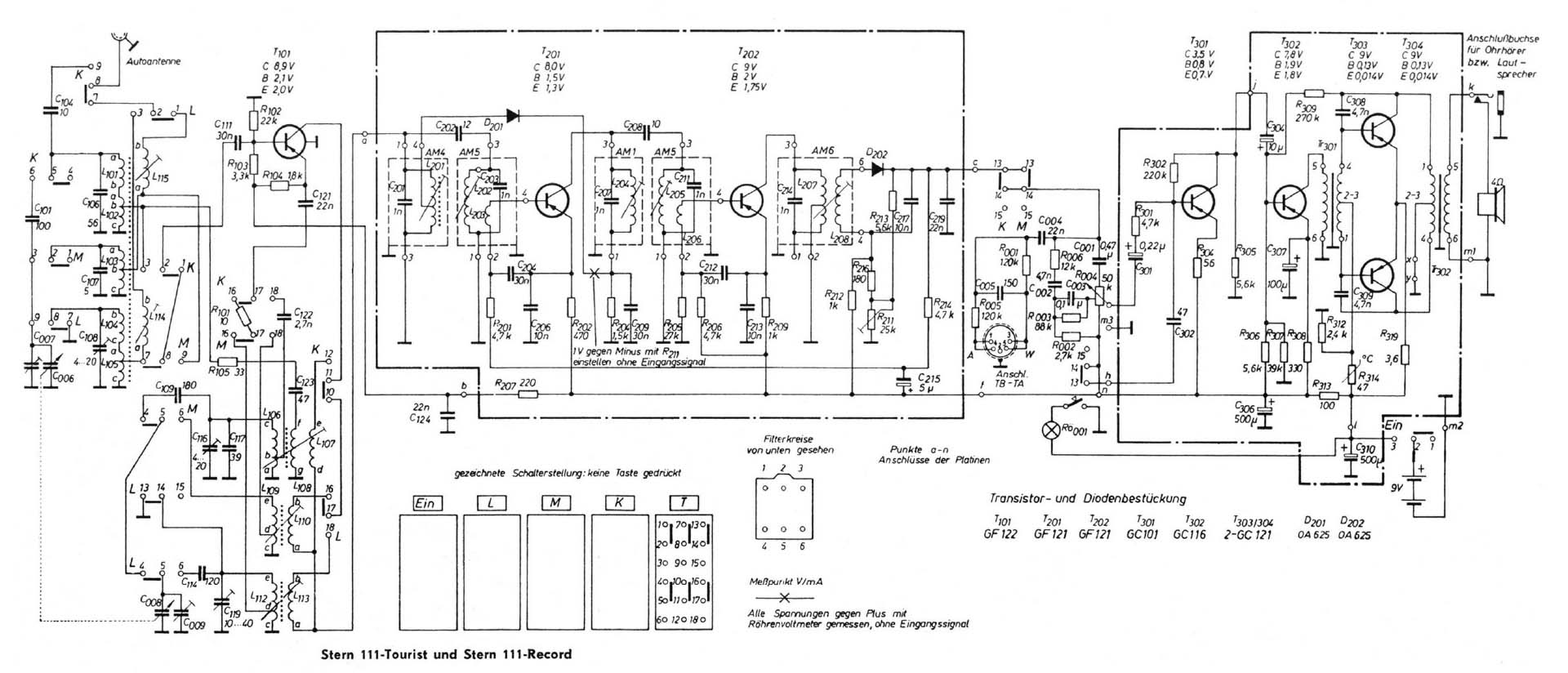

To meet the challenge of climate change, there are two ways in which market mechanisms can drive greenhouse-gas emissions lower, particularly the most prominent gas, carbon dioxide (CO2). Each way is designed to “put a price on carbon”—that is, to compensate for the external costs of carbon emissions to the environment and the economy that are not accounted for in normal market-pricing.

The most direct means is to tax carbon emissions directly. This could be done by taxing the emissions from plant smokestacks and car exhaust. But a simpler and less expensive way is to tax carbon fuels – – coal, natural gas, and oil—when they are introduced into the economy according to the emissions that will be created when they are combusted. As the tax is increased each year, total emissions should ramp down.

A second, more indirect method called “cap and trade” is a regulatory regime imposing progressively more stringent limits on carbon emissions each year from power and industrial plants that requires each covered facility to purchase and surrender permits for each metric ton of CO2 it emits, but allows regulated industries to “trade” permits in an open marketplace. This theoretically allows a broad segment of the economy to make reductions at the lowest overall cost. The trading price of a permit tends to reflect the average imposed societal cost of each reduction. As the number of permits sold by the government at auction decreases each year, the price should rise and emissions trend downward.

“Cap and trade” is a regulatory regime imposing progressively more stringent limits on carbon emissions each year from power and industrial plants that requires each covered facility to purchase and surrender permits for each metric ton of CO2 it emits, but allows regulated industries to “trade” permits in an open marketplace.

Almost all economists and policy experts agree that placing a direct tax or fee on carbon emissions to compensate for “external” costs—rather than fashioning a complicated regulatory/trading system—is more effective, less costly, and more transparent. Assuming the tax level and ramp up are fixed and predictable well in advance, the tax approach also makes it easier for firms to make rational long-term capital investments, and tends to incentivize low-carbon consumer choices. By contrast, the price of permits in a cap-and-trade system cannot be predicted and will vary with market conditions that cannot always be foreseen.

Nonetheless, for the past two decades, climate policy in both the EU and the United States has been dominated by the cap-and-trade approach. In both the US and the EU, a direct carbon tax has long been perceived to be too politically “radioactive” to command the broad support necessary to enact it. Of course, a cap-and-trade system also drives up the price of energy produced from carbon fuels, but the effect was believed to be less visible to the public and therefore more acceptable.

Cap and trade originated in 1990 in the US Clean Air Act to reduce sulfur emissions from power plants causing acid rain. Then, in negotiations leading up the Kyoto Protocol in 1995-96, the United States proposed that an international version of cap and trade be adopted allowing countries to “trade” carbon or greenhouse gas allocations with each other. Many nations, including those in the EU, opposed this approach as a loophole intended to allow the United States to avoid its own domestic obligations by buying cheaper emissions reductions elsewhere. Nonetheless, the US position was adopted.

Ironically, the US never joined the Kyoto protocol and virtually no carbon trading ever took place globally. But when it came time for the EU to adopt community and national rules for meeting its Kyoto obligations, it too turned to a cap-and-trade system to ensure emissions reductions from the power and manufacturing sectors. This system, the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), now covers about 13,000 facilities and roughly half of all EU carbon emissions. Germany had originally wanted to adopt a carbon tax instead of this regulatory approach, but some other countries were opposed and a unanimous vote of all members is required to adopt any new community-wide tax. (Germany did adopt an initial energy tax and still has electricity, fuel and energy taxes, but they are not calibrated to the carbon content of various fuels and therefore do not provide much incentive toward use of or investment in lower carbon fuels.)

When the US Congress finally addressed climate policy beginning around 2004-05, the only program that appeared to have political viability was some form of cap and trade. A carbon tax was not seriously advanced. But the effort to design a comprehensive economy-wide cap-and-trade system was hugely complicated, both technically and politically, and crashed spectacularly in 2010. In spite of a supportive president and Democratic control of both houses of Congress, herculean negotiations to fashion a complicated thousand-page bill with concessions to dozens of vested interests barely passed the House of Representatives by a single vote, and made little progress in the Senate.

Since 2010, extreme political polarization of the climate debate that has developed in the US, added to Republican control of both houses of Congress and then the White House, has stalled all prospect of national climate legislation. Advances in climate policy have been limited to efforts by city and state governments, particularly California, and to efforts in the second Obama term to enact regulations for the electricity sector under existing law (now withdrawn by Trump). California also enacted a state-wide cap-and-trade measure (in addition to a suite of other climate policies) as have a group of Northeast US states to reduce power section emissions on a regional basis.

Since 2010, extreme political polarization of the climate debate that has developed in the US, added to Republican control of both houses of Congress and then the White House, has stalled all prospect of national climate legislation.

With the House of Representatives now in Democratic hands, the shape of US national climate policy is now about to become the subject of new debate in Congress and the public for the first time in a decade. Surprisingly, that policy will most likely have a direct price on carbon—a carbon tax or fuel fee—at its core. In other words, the approach that has long been touted by experts as the best and the least expensive, but considered politically unachievable, may now be the only program that can command broad public and at least some bipartisan support.

In the EU, as well, flaws in how the cap-and-trade system has priced carbon are now being hotly debated as the community shapes its policy for the period 2020-30 and beyond.

What forces are moving the tectonic plates in the US climate policy geography?

First, there is growing public concern in the US after President Trump’s repudiation of the Paris Climate Accord: as the rest of the world taking the risk of climate change seriously and committing to real action, the United States cannot afford to simply ignore the issue indefinitely and do nothing.

Second, in 2018 Americans were bombarded with an avalanche of new warnings about the imminent threat from climate change, ranging from a new report from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reflecting growing worry by a consensus of the scientific community, a stark assessment by US government agencies of the impact of climate change on the US economy, and studies of increasing storm intensities, fires, and drought, along with accelerated melting of Arctic and Antarctic ice.

Third, growing public attention has also been fueled by more media coverage of how US cities and states, other countries, and major international companies increasing commitments to reduce their own greenhouse gas emissions, of polls showing younger Americans of all political persuasions overwhelmingly support climate action, and even the intervention by Pope Francis to emphasize the global threat of climate change.

Fourth, from prominent figures on both the Right and Left have come proposals that a carbon fee could be an economically and fiscally sound way to address the climate challenges and could uniquely meet several of the country’s priority needs and concerns. The crash of cap-and-trade legislation in the US Congress halfway through the Obama Administration left an extraordinarily sour taste and a legacy of failure for the regulatory approach.

But a carbon tax has two significant advantages: It would make complex new regulation unnecessary and even render existing regulatory authorities obsolete. This is an important selling point because one thing that President Trump’s base, traditional Republicans and much of the business community have in common is their distaste for federal regulations, both existing and future. Moreover, a carbon fuel fee would generate a huge amount of new federal revenue. A fee beginning at $35 per MT (metric ton) of CO2 and rising gradually each year imposed on coal, oil, and gas would produce approximately two trillion dollars of new revenue over ten years. This is an order of magnitude greater than any other tax reform or major tax measure that has been seriously considered in recent years. A third of this revenue returned as a dividend to low- and middle-income families could fully compensate more than half of all American families for increased energy price, leaving well over a trillion dollars to invest in infrastructure, create jobs, grow the economy, and reduce our spiraling budget deficit. Alternatively, even more could be given back to families as climate “dividends,” along the lines of carbon-tax pricing that Canada has introduced, intended to reach a national common price of C$50 per MT/CO2 by 2022. Under the Canadian approach, which returns 100% to families, the government estimates that well over 70% of the population will “come out ahead.”

A fee beginning at $35 per MT (metric ton) of CO2 and rising gradually each year imposed on coal, oil, and gas would produce approximately two trillion dollars of new revenue over ten years. This is an order of magnitude greater than any other tax reform or major tax measure that has been seriously considered in recent years.

Meanwhile, the attractiveness of direct pricing of carbon appears to be gaining momentum in other parts of the world, as many governments begin to develop more detailed plans to meet commitments made in the Paris Climate Accord. Even in the EU there have been proposals to replace the ETS with a tax providing a more predictable long-term price, though that’s very unlikely, given the unanimity requirement for adopting a new EU tax. More likely to get serious consideration is a proposal to tinker with the ETS system by building in a “floor price” for permits, or imposing a national tax (as the UK now does) on top of the permit price where it is deemed too low. These recommendations reflect design flaws in the original EU ETS. Emissions caps were not set aggressively enough, given the financial recession and too many free permits were given away to industry. This caused the market price of permits to sag far below anticipated levels for much of the past six to seven years. Similar failures occurred in the California and Northeast regional cap-and-trade systems in the US. The higher price signal intended to incentivize new investment in low-carbon technologies was therefore almost completely eroded.

In both the US and EU, effective climate progress is probably going to depend on some mixture of pricing and regulatory mandates. My goal as a fellow at the Academy this spring is to find out more about how the relationship between and combination of these approaches provides the most effective market signals, what the US can learn from the EU’s more than ten years of climate policy experience.

George T. Frampton is the co-founder and CEO of Partnership for Responsible Growth, which advocates for free-market measures to combat climate change. During the Clinton administration, he was chairman of the White House Council on Environmental Quality and Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Fish, Wildlife, and Parks.