Spring 2020 Fellows Respond to Coronavirus

Despite social distancing and working from home, intellectual life at the American Academy in Berlin continues. We asked our spring 2020 fellows to share their thoughts on how the coronavirus has impacted their residential fellowships and their broader concerns. This is what they had to say.

Future Perfect

by Amanda Anderson

John P. Birkelund Fellow in the Humanities;

Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Humanities and English; Director, Cogut Institute for the Humanities, Brown University

The speed with which the global pandemic reached critical stages in Europe and the US and the extraordinary changes it has brought to ordinary life create conditions in which it is hard to feel as though one can write with any assurance about it. Its contours, and one’s response to them, seem to change almost daily, and in unpredictable ways. For those lucky enough to have continuing means of income and the luxury to write a reflection such as this, it seems only possible to say that, perhaps, one day, we will have processed it, or processed some aspects of it.

One of the key contributions of trauma theory was the development of the concept of complex as opposed to simple post-traumatic stress disorder. In the case of complex trauma, the injury is not a single event but takes place over time, repeatedly and enduringly, and produces syndromes difficult to overcome. It is clear that in the current crisis many individuals and populations are witnessing and experiencing both simple and complex trauma: simple and immediate trauma in cases of acute illness and loss, and slow and complex forms of trauma including challenging forms of social isolation, persistent stress and anxiety on the medical and essential-worker front lines, and intensified disparities in access to health care and ability to shelter in place with safety and support.

My own recent scholarly interests have been divided between making the case for a renewed understanding of political liberalism and exploring the role of psychological frameworks in contemporary culture. My thoughts in the time of coronavirus seem to move back and forth between these two areas. I have found myself fascinated by the social psychology of the pandemic, and in particular the drive toward normalization evident in so many forms of response. This drive toward normalization takes many forms: it first appeared as the inability to imagine that the novel coronavirus was really going to become a global crisis, or a crisis for one’s own region, or a threat to one’s way of life. Now that such denial is no longer possible, there are attempts to insist upon “a return to normalcy” as early as possible. But part of what a crisis of this magnitude reveals, as many are aware, is that what appeared as “normal” was already a precarious set of conditions involving grave vulnerabilities and injustices – this is particularly the case in the US where healthcare access is so unevenly distributed, and where enduring structural disadvantages exacerbate disease outcomes. It is impossible to listen to or read certain fluff stories – about recipes to try during isolation, or how to exercise at home – without being acutely aware how dire the situation is for the homeless, the disabled, or the unemployed. Which brings me to my interest in the promise of an engaged form of political liberalism: What I most hope for at present is that this situation will have produced major transformations along the order of the New Deal or the Great Society, transformations which reflect renewed acknowledgment of the importance of governmental institutions, expert knowledge, strong infrastructure, and widely available health care and disease prevention.

Corona thoughts

by Carolyn Chen

Inga Maren Otto Fellow in Music Composition

Composer, Sound Artist, and Performance Artist

I make experimental music. Mostly, I make scores for others to interpret. Sometimes I play in my own pieces (usually with untrained voice and movement, sometimes with guqin, clarinet, or piano). Occasionally I play other people’s music, too. This is the work that occupies most of my imaginative life. Of course, it is not the work that pays most of my bills. I also teach piano and tutor math and other subjects. Like most of my colleagues in contemporary music, I am a contingent laborer. Though I’ve been lucky to accumulate steady work in the last few years, it has always been clear that employment security is not an aim within my control.

Even in economically flush times, making ends meet as a freelance musician is already precarious. In Los Angeles, where I live, most of my colleagues cobble together teaching and gig work from many sources, driving across the city and neighboring counties to pick up a class or a few lessons at a community college or youth music school here and there, in between pick-up orchestra rehearsals or recording sessions – all while attempting to find time to practice the music they care most about at the ends of the day. This is a musical world that runs far more on love and good will than actual funding.

The threat that the pandemic recession poses is existential. Musicians are losing income not only from cancelled concerts, but also loss of supplementary work that many perform to stabilize their earnings. In the last recession, one friend lost all of her students over the course of a week. All of this is not even considering healthcare prospects for freelancers who may not have insurance.

As a composer, much of my work already exists in home isolation, imagining things to do with other people when we can meet again. I research online and talk with most collaborators over the phone anyway. Mostly what I need are quiet and floor space, both of which are in plentiful supply here. Needless to say, being at the American Academy in Berlin at this moment is an extraordinary privilege. Never in my post-Phd life have I been as economically secure as I am this semester, and never have I lived for so long in an environment where the music I make doesn’t feel like a somewhat-embarrassingly obscure and unprofitable hobby. However, it has been difficult not to worry about how my community will survive. Being in Germany at this moment has highlighted how dramatic a difference it makes when a state values supporting the arts and the health of lower wage earners in general.

In a time of anxiety, it has been heartening to see people valiantly finding ways to stay connected through music – streaming concerts from home, or reconstituting ensembles through video editing. Also inspiring are the oft-shared videos of songs sung across apartment building balconies or in between landings of a staircase. The spirit of communal music-making is a beautiful thing to witness. The songs sung in these situations, though, must be shared cultural knowledge. Songs that are unknown face a more fragile future.

Losing Touch

by Veronika Feuchtner

Anna-Maria Kellen Fellow;

Chair and Associate Professor of German, Department of German Studies, Dartmouth College

I am a handshaker, a hugger, a kisser. If the term weren’t a horrible euphemism for sexual aggression and so profoundly gendered, I would describe myself as “handsy.” Maybe it’s time to reclaim this term from the creeps. I am a handsy woman. Consensually and respectfully handsy. I love that first moment of connection, when we meet or when I see you again. Hi. I see you. I hear you. I smell you. I feel you. I am fully here with you. With all my senses. I meet the entire bodily mess that’s you. I look into your eyes and reach out for your hand. Sometimes it’s sweaty, sometimes it’s cold, but it’s always, always carrying germs.

So far, I hadn’t given that a second thought. And it’s not for lack of getting sick. Every winter, the small rural campus I teach in turns into a bustling transportation hub for globally circulating viruses, the Heathrow of seasonal pandemics. By the second week of February, my students are dropping like flies. Even after submitting to the yearly ritual of the staff flu vaccine, I still experience the eight-week deep dry cough that makes every lecture, movie, or, God forbid, classical concert an anxiety-ridden occasion for spontaneous side-solo-performances of spasmodic contortions. I have a cough lozenge at the ready in every single pocket of every single layer of my inoffensively colored, heat-retaining, hi-tec-fleece wardrobe.

Despite my yearly appointment with pandemia, I cultivated a haughty air of mockery towards the culture of viral alertness. First of all, perpetually inoculating myself against last year’s flu struck me as an anachronistic act, almost poetic. To this humanist, it seemed like science’s version of a Hail Mary. As if disease specialists had learned precisely what they shouldn’t have learned from the humanities (and nothing else). “Oh, YOU throw yesterday’s books at today’s problems? Watch what WE can do with these old viruses!” Deconstruction aside, in a few instances I’d like my science to be positivist. Of course, I snickered at the campus initiative that advocated alternative, flu-conscious modes of greeting, like a blasé nod in my general direction, or if you felt particularly affectionate, an awkward elbow-bump. It didn’t help that it came on the heels of that other initiative which banned individual office trash cans, so that I had to weigh a lengthy walk to the deserted central hallway against every urge of peeling open a single orange, or more to the point, a couple of candy bars while grading into the wee hours. To me, the nodders were hiding social awkwardness and a pathetic lack of cosmopolitanism under the guise of germophobia. And I couldn’t quite decide what was worse.

But now Corona had me at hello. And this hard-core hugger had to draw the line. Now we all live without the touch of those we don’t live with. It is a strangely disembodied existence. In Wim Wenders’ filmic love poem to humanity Wings of Desire, it is foremost the desire to experience the sense of touch that leads some angels to forfeit eternal life and to embody themselves as mortal humans. “I can’t tell you how good it is to be here,” muses one former angel, the actor Peter Falk playing himself, leaning against a fast food counter on a cold winter evening, “just to touch something.” Sensing the presence of an angel, he tells him what the human sensory experience is like, to reach for something and feel its texture, to smoke, to have coffee, maybe even at the same time and with someone. Then he reaches out to shake the angel’s hand. The angel reaches back, but he can’t feel the human hand. He can’t connect with his friend. In the next scene, the angel, Damiel (Bruno Ganz in his most iconic role), takes the leap, and becomes human. In his last moments as an angel, he imagines that he will embrace the woman he fell in love with and that she will reciprocate his embrace.

Connecting with other humans through touch is not only a deeply desirable part of living human relationships, it is vital to human existence. In the 1940s, the psychoanalyst René Spitz observed that hospitalized babies had better chances of survival the closer they were positioned to the nurse’s station. The few more instances of human touch, of the affection and attention contained in it, could mean the difference between life and death. Besides a long line of clinical evidence for the benefits of touch, exists also a long line of psychoanalytical, anthropological and philosophical thought that argues that touching others is crucial to the constitution of the self. In his last published essay, “Eye and Mind,” the philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty wrote about how the human body becomes present in touch, and how “between hand and hand a kind of cross-over occurs, when the spark of the sensing/sensible is lit, when the fire starts to burn…” Feminist thought has also early on pointed to the embodied nature of perception and consciousness, and furthermore illuminated the social threat that female bodies were thought to pose through vision and touch with their bodily “mess” and “the most incredible range of busted boundaries,” as Jacqueline Rose recently described it. The psychoanalyst Susie Orbach has wondered about why we use the word “touchy” to mean “sensitive” on the one hand, and “risky” on the other: “Does our language know more than we acknowledge as analytic clinicians about the deficits of not being adequately touched and the consequence then of becoming insufficiently emotionally resilient?” If the sense of touch is so central to our emotional survival, the way in which we navigate the world, the way we experience ourselves as human and humane, what does it mean then to lose touch in the times of Corona? Stephan Weil, governor of the state of Lower-Saxony, which was especially hard hit by the virus, believes that the “good old handshake,” a bastion of German social etiquette, might be permanently retired. If our brave, new, viral world should truly not allow any more for the handshakes and embraces of friends, acquaintances and strangers, we have to think of alternative ways of how to keep touch in our lives, how to feel each other, how to share our messes, and how to retain our humanity. I am afraid, for this handsy woman, an elbow bump just won’t do.

What COVID-19 Means For the Global South and Says About the North

by Moira Fradinger

Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in the Humanities;

Associate Professor of Comparative Literature, Department of Comparative Literature, Yale University

By now, April 2020, I have seen so many videos reminding me how I have been washing my hands incorrectly for decades that every morning, I walk half asleep toward the bright white-tiled bathroom of my semester-long residence at the American Academy in Berlin. An automated procession of images turns on inside my brain as I stare at the tall translucent mirror. It is a display of single pairs of hands, under majestic waterfalls and resplendent soaps, always in the protected privacy of an indoor, white sink.

Now, in that perilous threshold between sleep and wakefulness, leaning to touch shiny metal taps for water, my morning ritual is enveloped by soft slow motion flashes of beautiful hands of all the colors of the world, cleaning themselves lavishly in pristine lavatories, with careful manicures. They use perfectly treated chlorinated water and exquisitely scented soaps.

These ubiquitous handwashing-instruction videos generally appear to me alongside COVID-19 charts with dead counts, often segregated by countries if they refer to the Global North. When they refer to the Global South they refer to “regions.”

A few days ago I inadvertently clicked on one video by the US Center for Disease Control. It used sterile images, nurses’ aprons, and educational questions. The most difficult one comes at the end: “What if you don’t have water?” The professorial answer is: “Use antibacterial disinfectant with at least 60% alcohol.”

On July 28, 2010, the UN recognized access to clean water as a human right. UN news in January 2020 said that “in Haiti some 35 per cent of Haitians lack basic drinking water services and two-thirds have limited or no sanitation services.” While I switch on the tap with clean water every morning, in many parts of the world women walk for hours with a pot on their head to find it. According to the WHO and UNICEF, there are three billion people in the planet who do not have basic access to soap and water in their homes. That means around 40 percent of the global population does not have the basic facilities that are required to carry out the hygiene recommendations to stay alive.

I learned the expression “water stress” on the Water, Peace and Security (WPS) website, an organization founded in 2018 by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a consortium of nonprofit organizations and independent think tanks. They have recently developed a tool to identify areas of potential violent conflict over water around the world. I recall the scandals of billionaires buying lands with rich streams of water in Patagonia in the 90s. Friends started to speak about the “third world war” as “the water wars.”

It reminds me of the UNICEF 2019 video for Water Day: “Water is a weapon of war: more children die for lack of it than for bullets.” The child in the video says I, the viewer, “am using a weapon of war.”

I am using a weapon of war to stay safe and keep others safe in the small corner of the world where the pandemic has kept me locked in place. Actually, several weapons of war. Every measure taken in the global north is a weapon of war. As I #Stayhome, self quarantine and keep 1.5 meters apart from others, I wonder: How many die for lack of houses, homes, safe homes?

With all my weapons of war, I can follow the measures that protect me and protect my own. They seem to flatten the curve of infections in this part of the Global North. But they are not global measures for a global disease. They leave out three quarters of the world. And thus, because viruses do not respect borders, they leave us all exposed to the next pandemic.

Three months before the coronavirus arrived, the Global South was aflutter with dirty hands holding tight together in public plazas, feeling the solidarity of protest for freedom and global change from Hong Kong to Chile. An expression of happiness as bodies rubbed against each other in close embraces in massive rejections of 40 years of structural adjustment policies that sent the middle classes to poverty, and exponentially increased the gap between the rich and the poor at levels not seen in the last 70 years.

The round of protests travelled the world in 2019, just as the virus is now happily going across the planet. It will not be impressed by my weapons of war: treated water, houses where everyone has their own room, homes where everyone feels safe. The virus will survive them as long as we live in the systematic expulsion (not just exclusion) of billions of peoples across the world from things as basic as water.

Every virus comes with the same message: pandemics are political and thus must be solved with structural changes in our value systems. As long as we can afford clean water and lavish soaps, solid houses and safe homes because three out of four people in the world cannot afford them, death will be at around the corner.

Berlin Afar

by Paul LaFarge

Writer, New York;

Holtzbrinck Fellow

I write to you from the Berlin in my mind: the city where I spent the month of February, and which I still dream about. I should tell you that it has undergone some transformations since my abrupt departure. For one thing, it has hills now; for another, in my Berlin, it is still winter. Parking is difficult, and people drive mopeds recklessly through the slush. On the other hand, the stores here are all open. They sell the curious objects I coveted when I was seven: mysterious toy figures bound in fabric and wire; illustrated guides to places even more imaginary than my Berlin. The people here are kind but they’re all in a hurry. Some of them look like people in the real Berlin, and others look like people I knew in elementary school. I want to ask how they are holding up in this strangest time, or just get directions — I keep coming back to the same places, over and over — but even in dreams, my German isn’t up to the task.

Popular colors here: gray, brown.

How is it in the real Berlin? I heard a story about two friends sharing a bottle of wine on a balcony. I hear that rice is back on the shelves. I hear the fox that lives near the American Academy had a baby fox, a kit, as they’re called here. All the pictures I see in the newspaper are of an empty, hard city, where one or two people shirk across an enormous sidewalk. Is that what the real Berlin is really like, or just a photographer’s dream?

In my Berlin, people are out, yearning.

Or at least, I’m yearning, although I couldn’t say for what. Someone I met in February, or the love I missed as a child? It’s hard to tell when you can’t speak. It’s hard to tell when you are, in fact, alone, asleep, trying to make a world as best you can, now that the real one has seemingly vanished.

I wonder if I’ll figure it out, if I stay here long enough.

I wonder what it’s like outside.

But what can we do? Even if I were with you in real Berlin, I’d probably be living part-time in dream Berlin. (Or maybe I’d be quarantined in dream New York, as sometimes happens.) And for all I know, you’re in dream Berlin, too. Does yours have balconies? Are you also lost? Is it snowing? The newspaper says things are better there than they are here, but still, I worry.

I hope to join you again soon, in one place or the other.

The Writing Cure

by Liliane Weissberg

Anna-Maria Kellen Fellow;

Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor in Arts and Sciences, Departments of German and Comparative Literature, University of Pennsylvania

It was not supposed to be like this. I envisioned a semester in Berlin during which I would encounter a constant flow of scholars and artists both at and outside the American Academy; take advantage of the city’s rich cultural offerings; meet old friends and make new ones. I was to spend time on research and writing, of course, but not much on sleep. I wanted to see everyone, be everywhere, do everything, but by early March, news about virus infections turned grim, and I could neither deny the gravity of the disease anymore, nor the danger we were all facing. Our life at the Academy changed far too soon.

My husband, who had visited the Academy early on, suggested an obvious reference point for us in Boccaccio’s Decameron, where ten people escape Florence during an epidemic and seclude themselves in a villa outside the city. There, they bide their time by telling each other stories, and thus create a literary masterpiece of famous novellas. Oddly, the pressure for us was still on.

While the comparison was compelling, it was not compelling enough. Yes, the Arnhold mansion was a splendid lakeside castle removed from the city’s center, and we were even ten fellows here as well — although only at the very beginning. But what did Boccaccio know of social distancing? Could the lords and ladies of his brigata have told such wonderful tales with a 15-minute limit for face-to-face encounters? And did not that earlier cohort return to the city too early, without the benefit of meetings about best practices to avoid the plague and almost daily email updates on its progress?

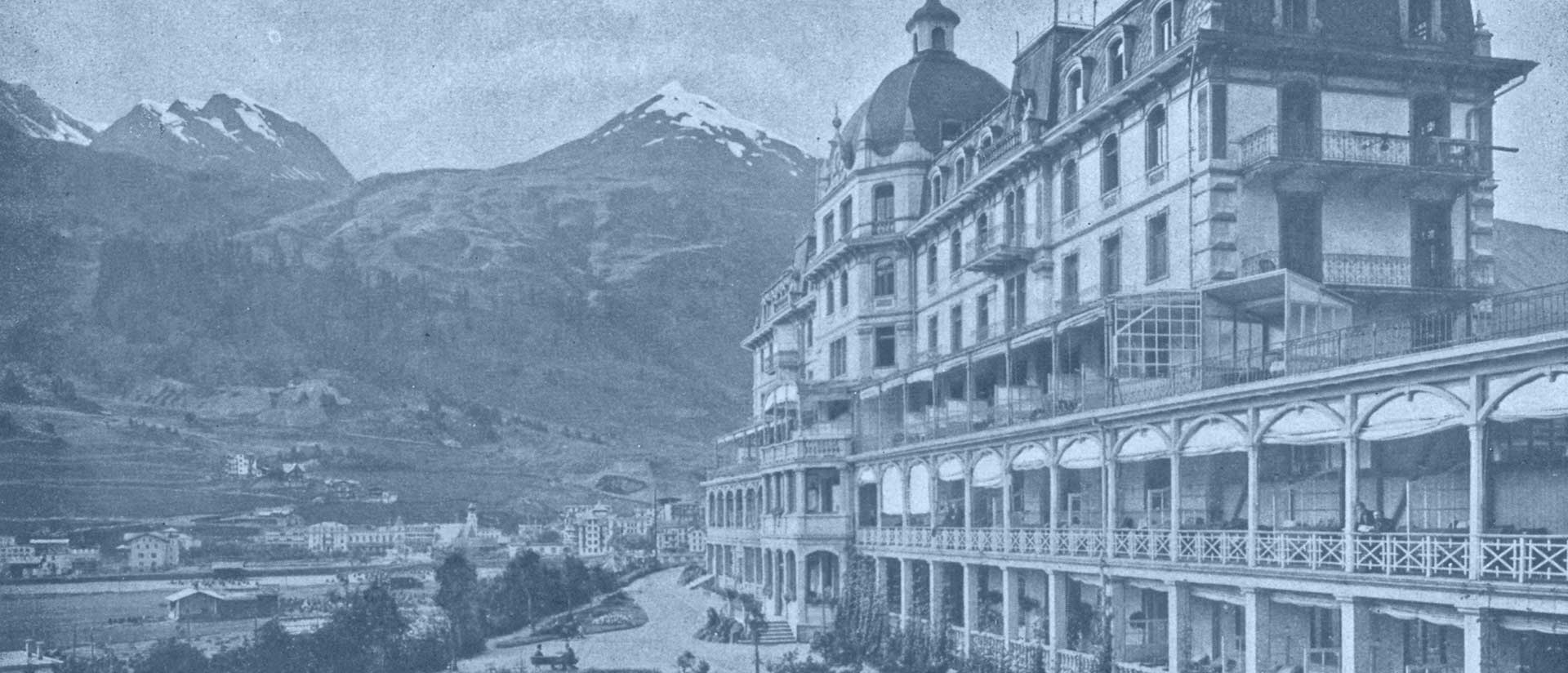

I wanted to confront my deep anxieties, but also look for more positive examples in my own field of research, the long nineteenth century. Of course, there were epidemics during that period as well. The city of Hamburg, for example, experienced seven outbreaks of cholera between 1831 and 1892. But people did not only escape the cities to protect their health, they also sought places that would heal them, and where they could find a cure. Subjects whom I study frequented resorts like Teplitz, Karlsbad, Marienbad, or Baden-Baden to take the waters, inhale mineral salts, and breathe fresh ocean or alpine air; they were searching for doctors and proper potions that would relieve them of their ailments, or simply extend their youth and vigor. Yes, these places were exclusive too; magic mountains or valleys that sought to establish alternative worlds. Wasn’t the American Academy such a place that could restore one’s body and spirit? Did it not offer a splendid alternative to the everyday?

Instead of taking the waters, I have engaged in a writing cure. Every morning after breakfast, I make my way to the office pavilion in the garden, and settle down in my study. I have been very lucky: I had completed most of my archival research by early March, and ordered many books from Berlin’s various libraries in advance, they appeared on my desk miraculously after my arrival. As these libraries closed, none can be recalled. My lectures and trips were cancelled, and I received the gift of time. In the past weeks, I have begun to reassess the frantic pace of my life, and have gained a renewed ability to focus and concentrate. I have learned about a new German word that has entered philosophical discourse of late, Entschleunigung. I have realized anew how fulfilling I find my work. And as time has begun to stretch out, my productivity has actually increased.

These are lessons learned about my way of working that I will have to hold onto in future. But at the Academy, not all has been about work. The fellows and partners who remain at the Villa Arnhold have deeply bonded with each other, creating opportunities to meet in a time of restricted conditions. We have grown very close to many of the Academy’s staff members who have gone far beyond their call of duty to make everything here work for us. Perhaps we did not experience Berlin’s cultural and social life as previous fellows did, but our time here has been extraordinary and I suspect that we will all value it for the rest of our lives.