Fresh Air

Thomas Mann and the literature of contagion

By Susan Bernofsky

As I sit in my apartment in New York City, at work on my new translation of Thomas Mann’s great novel The Magic Mountain, I frequently have occasion to consider the relationship between illness and mobility. If not for the worldwide Covid-19 pandemic, my partner and I would be packing our bags for Berlin to begin an eagerly anticipated residency at the American Academy. Instead, we anxiously watch the news for signs that the European Union’s restriction on travelers from the United States will soon be eased, if not lifted.

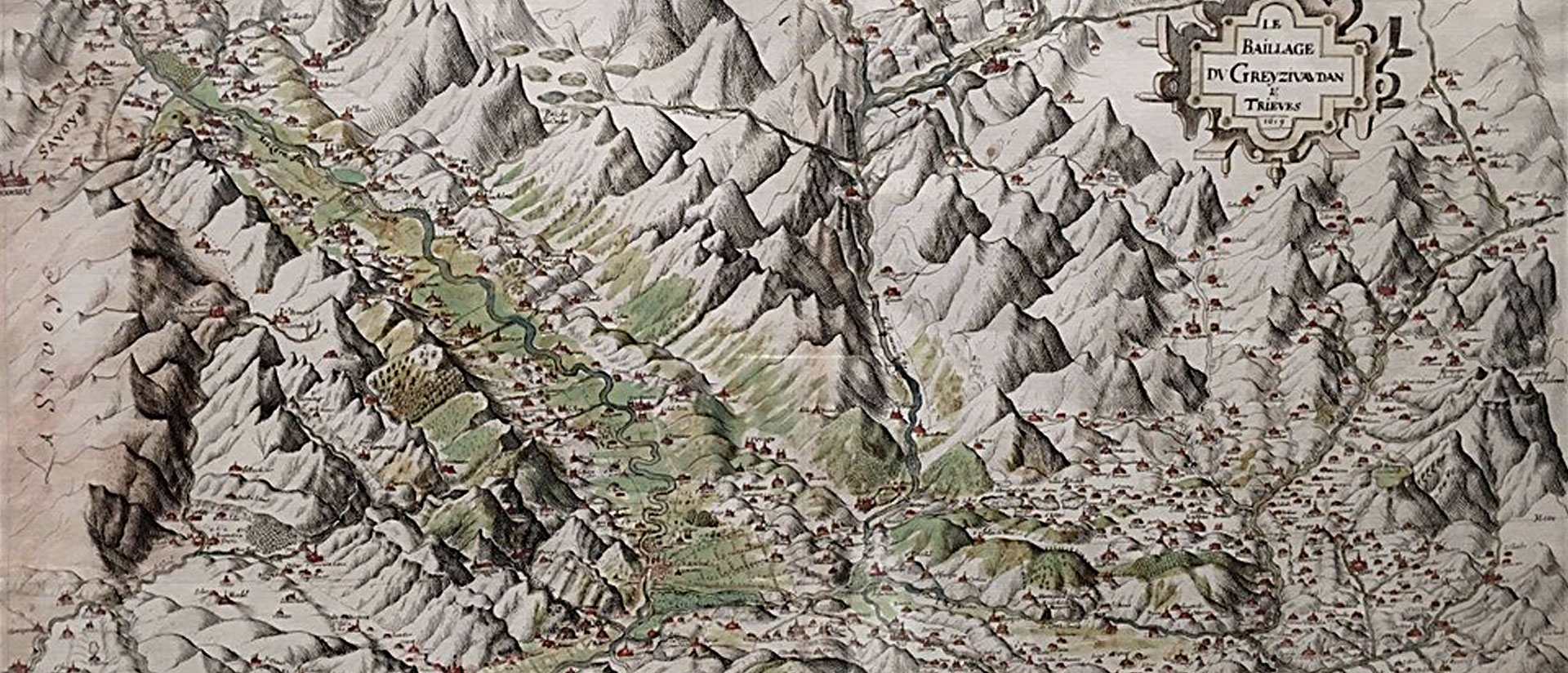

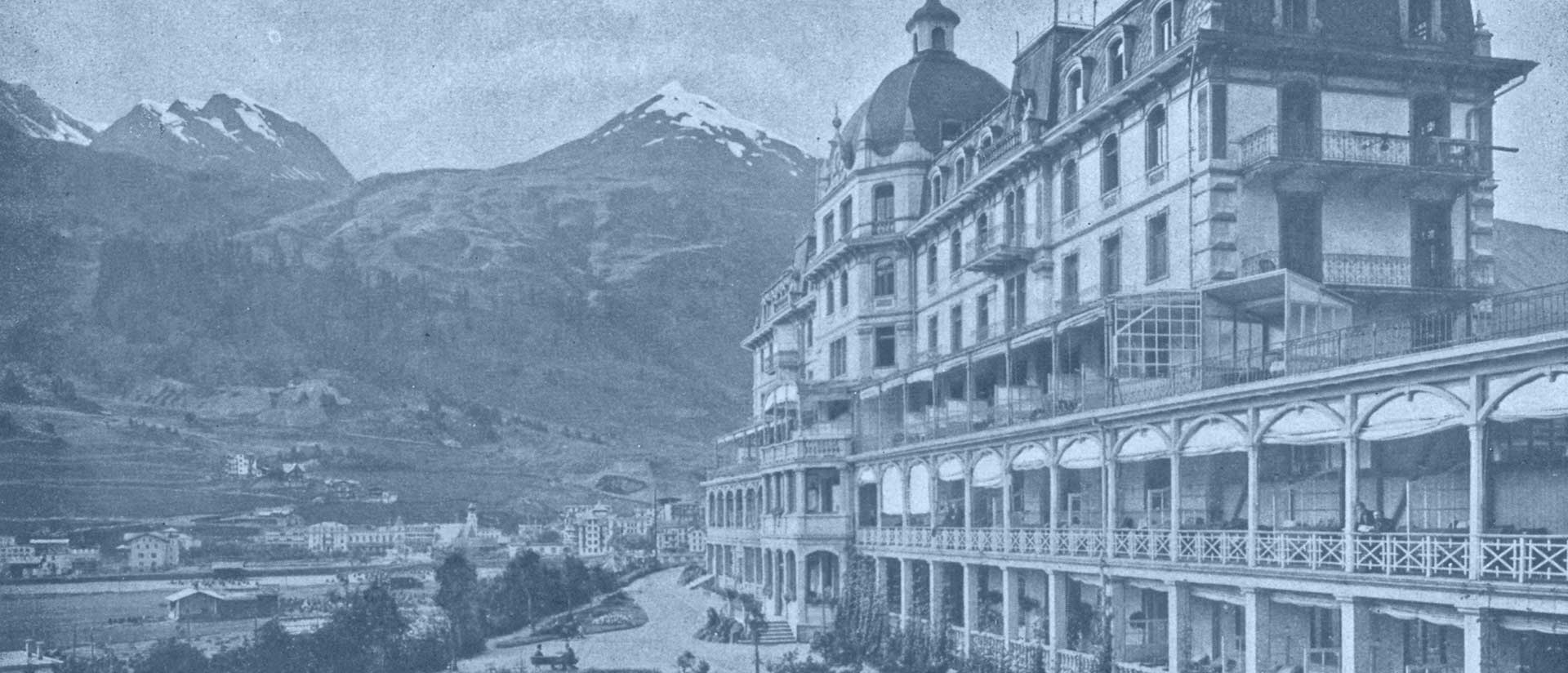

Thomas Mann began his novel concerned with a very specific contagious illness—tuberculosis—in 1913, shortly after Mann’s wife, Katia, spent several months recuperating from a pulmonary infection at a sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland. Mann envisioned a short, satirical companion piece to Death in Venice. But the scope of the project expanded once he started writing, and it was soon clear that it would become a substantial work. The book’s path to completion was anything but direct. Mann kept interrupting work on it to return to the perpetually in-progress novel he expected to be his post-Buddenbrooks magnum opus: The Confessions of Felix Krull, Confidence Man. Once the Great War began, he immersed himself in politics as well, with magazine pieces that eventually became the 600-page nonfiction volume Reflections of an Unpolitical Man, published in 1918. After the war ended, Mann’s thoughts returned to Davos and the story of the “simple young man” Hans Castorp, who travels from Hamburg to the Alps to visit his consumptive cousin, Joachim. Hans’s three-week stay extended to seven years, and Mann’s projected hundred-page work sprawled to a thousand by the time it was published, in 1924.

Thomas Mann began his novel concerned with a very specific contagious illness—tuberculosis—in 1913, shortly after Mann’s wife, Katia, spent several months recuperating from a pulmonary infection at a sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland.

The Magic Mountain is set in the years leading up to the Great War and concludes when Castorp is drafted, following the outbreak of hostilities. The storyline thus ends prior to the global influenza pandemic. If Mann had decided to include it in his novel, he would have had to completely rethink his story to incorporate it, since the pandemic arguably devastated Europe even more decisively than the devastating war itself (which Mann also bracketed out of his novel except for a single impressionistic battle-scene, at the end). Indeed, the epidemic killed more people worldwide than World Wars I and II combined. The disease was misleadingly labeled “Spanish flu,” though it probably did not originate in that country; news media in neutral Spain were merely the first to report on the pandemic. They could because they were not subject to the press censorship imposed in neighboring combatant countries, whose governments feared weakened morale.

The influenza’s many casualties in the sphere of German-language culture included Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Max Weber, and Sigmund Freud’s daughter Sophie. Franz Kafka, who had been diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1917, contracted influenza one year later, which contributed to the rapid decline in his health; he died in 1924, at the age of forty. It is remarkable that Kafka, for all his frustrating years of illness—including a series of partial recoveries followed by inevitable downturns—produced few texts in which illness plays a significant role. He wrote The Metamorphosis, his most important work about physical infirmity, two years before he began to cough blood.

The influenza pandemic hit close to Mann’s own home: his daughter Monika—eight years old—fell ill with the flu but recovered. He was well acquainted with the particular agony endured by those forced to watch their loved ones suffer from this severe illness that, still poorly understood, was taking so many lives. I believe this experience influenced his descriptions of lung ailments in the novel. Protagonist Castorp—truly an innocent abroad in the Swiss sanatorium—begins the novel shocked to hear the “utterly horrifying sound” of a tuberculosis patient hacking his lungs out. Castorp himself later becomes fluent in the language of consumptive expectoration. Here’s his first impression of the coughing of the (as yet unseen) “gentleman rider”: it “bore no resemblance to any coughing Hans Castorp had ever heard before. Indeed, compared to this, every other variety of coughing known to him was merely a glorious, healthy expression of life. This was coughing done under protest, not a series of discrete blasts but a hideous feeble flailing and wallowing in a muck of organic decomposition.”

Protagonist Castorp—truly an innocent abroad in the Swiss sanatorium—begins the novel shocked to hear the “utterly horrifying sound” of a tuberculosis patient hacking his lungs out. Castorp himself later becomes fluent in the language of consumptive expectoration.

The tuberculosis treatment practiced at Berghof Sanatorium as described in The Magic Mountain emphasizes the value of fresh air in vanquishing the disease. In the Davos of the novel, sitting out on a balcony in the cold air of a wintry afternoon is understood as cutting-edge therapy. Tuberculosis was only in the 1880s found to be caused by a bacterium—a discovery for which physician Robert Koch won the 1905 Nobel Prize. The disease had earlier been thought to be hereditary. With the new understanding of germs causing the illness, the importance of sanitaria located in mountainous regions replete with lots of fresh, cold, bacterium-banishing air was paramount.

Faith in fresh air’s ability to combat infection is also responsible for the impressive size of the radiators in my own New York City apartment, in a building that dates from 1922. During the 1918 pandemic, influenza spread especially fast in the city’s many tenement buildings, where large numbers of residents lived crammed together in underheated close quarters; windows were generally kept closed to preserve the little warmth available. In fact, this is one reason why in 1918 (as in 2020) lower-income communities were particularly hard-hit by the illness. Soon after the pandemic, under the influence of the Fresh Air Movement, the New York Board of Health mandated that all new buildings were to be supplied with large boilers and radiators, the goal being to intentionally overheat apartments. Residents would be forced to open their windows to maintain a comfortable temperature, facilitating the circulation of healthful, germ-dispersing fresh air. In 2020, while environmental considerations make us lament the wastefulness of the steam heat still a ubiquitous part of New York City life, the recommendation to keep indoor spaces well ventilated to reduce the spread of Covid-19 is just as important now as in 1918.

Soon after the pandemic, under the influence of the Fresh Air Movement, the New York Board of Health mandated that all new buildings were to be supplied with large boilers and radiators, the goal being to intentionally overheat apartments.

Of course, the purpose of the chilly balconies in Davos, where Mann’s tuberculosis patients aired out their lungs, was to cure existing infections rather than ward off new ones. Even so, I can’t help wishing I had my own nice private balcony as I huddle in my New York apartment translating this novel. Berlin seems very far away. And like Hans Castorp, who begins The Magic Mountain by embarking on the longest journey of his life, and then trades in this mobility for a seemingly endless stasis, I find my life, too, newly defined by immobility, watching time endlessly telescope as I translate my way through page after page of Mann’s masterpiece, highly conscious of the irony of translating during one pandemic a novel that took shape during another.

Image: Postcard of Sanatorium Valbella, 1915 © Dokumentationsbibliothek Davos.