In the Red

Democracy in an age of debt

By Steven Klein

Our political age is one of debt. The long shadow of the 2008 financial crisis continues to define politics. In the American Democratic Party presidential primary, Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have released dueling plans for who can forgive the most student debt—currently at $1.49 trillion. For many so-called millennials in America, the burden of student debt prevents them from taking out that other, more “responsible” form of debt—housing debt—and getting on the property ladder, a ladder made lucrative precisely because the broad access to mortgage debt inflates the value of real estate.

But even as attitudes towards debt vary between countries, its political ramifications are unavoidable. Germany’s household debt currently equals 52 percent of its GDP, as opposed to 80 percent in the United States. Yet Germany’s fate is still debt. Instead of domestic consumer debt, German banks rushed into Europe’s southern periphery, enabling the debt buildup that exploded during the Eurozone crisis, reshaping the European Union. Given the global interdependence of financial systems and flows, the effects of debt are no longer nationally bound—even if the liability for debts remains a national responsibility.

Debt is coming to redefine democracy, in ways the full extent of which is not yet clear. It is even less clear that our established political ways of thinking—about democracy, citizenship, and the relationship between democracy and capitalism—are adequate for confronting this new era. In an era of permanent debt, how does the hierarchical relationship between debtors and creditors relate to the egalitarian promise of citizenship? How does the continuous surveillance of credit ratings affect political freedom? And what can social democracy mean at a time when political communities are increasingly subject to the dictates of bond markets?

In an era of permanent debt, how does the hierarchical relationship between debtors and creditors relate to the egalitarian promise of citizenship? How does the continuous surveillance of credit ratings affect political freedom?

While this moment calls for new thinking, it is far from the first time that the principles of democracy have clashed with the imperatives of capitalism. Until the Great Depression, European economies were governed by the ideal of the market society and the straightjacket of the gold standard, which, along with the limited franchise, were designed to curtail the democratic reorganization of economic relationships. Few thinkers identified these tensions as astutely as the Hungarian social and political philosopher Karl Polanyi. Polanyi’s most famous work, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time, published in 1944, was largely neglected upon its release. Yet it has found a remarkable afterlife, becoming one of the key texts for debates about the relationship between democracy and capitalism. But Polanyi also provides some central insights for thinking about equality and citizenship in our age of debt—insights that could help discern how democratic institutions could master twenty-first-century capitalism.

Karl Polanyi: Prophet for Our Times?

Born in Budapest in 1886 to a Jewish family, Polanyi was raised in Vienna in the Austro-Hungarian empire, an empire that became a model for many postwar visions of a transnational liberal order. In his student days, Polanyi became an important member of liberal intellectual circles, but his experiences with “Red Vienna”—the historic experiment with municipal socialism—pushed him into dialogue with socialism. Red Vienna sparked some of the most consequential philosophical debates about capitalism, socialism, and democracy—debates that influenced, in addition to Polanyi, central twentieth-century thinkers like Joseph Schumpeter, Ludwig von Mises, and Friedrich A. Hayek. The birth and eventual collapse of the Republic of Austria inspired much of Polanyi’s writing. He sought to make sense of the promise of the socialist experiment as well as how global economic institutions and political dynamics thwarted democracy in central Europe. He experienced the consequences personally: the election of the “Austro-fascist” Engelbert Dollfuss in 1932 marked the end of Austria’s nascent experiment with democracy and Vienna’s with municipal socialism. While his wife, Ilona Duczyńska, remained in Austria to organize armed resistance to the new regime, Polanyi left for England, where he began working on what would become The Great Transformation, finishing it after moving to the United States.

Like all great social and political thinkers, Polanyi combines clear, simple slogans with a complex theoretical argument. Perhaps he was too successful; his slogans have often been taken for his argument. The slogan for which Polanyi has become famous—“society against markets”—belies the most significant thrust of his thought, which challenges the opposition between state and market. Rather, Polanyi’s thought advances two central insights: the first, that markets for commodities require non-market coordinating institutions to function; the second, that these non-market coordinating institutions form around three “fictitious commodities”—land, labor, and money. For Polanyi, the tension between democracy and capitalism resides in the interplay between these non-market institutions—institutions that blur the border between states and markets.

Polanyi argues that, with the emergence of modern industrial technology, Europe underwent a great experiment to organize all of society based on the ideal of the competitive market. Led by the model of the British Empire, liberalizers across Europe pushed broadly for the elimination on restrictions on trade and exchange. But most central in Polanyi’s telling was the need to mobilize the three factors of production—land, labor, and money—such that they would be fully subject to the fluctuations of the market. In each case, though, the push towards the market faces eventual political blowback and efforts to build non-market institutions that can recognize the non-economic significance of land, labor, and money. Take labor. Polanyi contends that there is a contradiction between the fiction of the labor contract and the reality of living, breathing humans who labor. In the long run, markets may clear—but, in the meantime, people need to eat. These realities are embodied in the formation of non-market institutions like labor unions, whereby wages are set based on a principle of reciprocal solidarity rather than the market principle.

Polanyi contends that there is a contradiction between the fiction of the labor contract and the reality of living, breathing humans who labor. In the long run, markets may clear—but, in the meantime, people need to eat.

But Polanyi’s central drama comes from the interplay between labor and money. For him, money is a fictitious commodity because it always plays two roles: from the perspective of the market, money should be a stable means of exchange, one that simplifies and facilitates trade and contracts. But money is also a political institution, one that secures the continuous flow of credit through the economy. For the most part, these two functions align, but periods of economic crisis and change can pull them apart. This is especially so as the self-organization of workers disrupts the operation of the market principle in relation to labor, preventing the deflation that would allow for the adjustment of international trade balances.

Polanyi contends that the development of central banking was a response to the increasing recognition that the gold standard was destructive, not just for workers but for productive business enterprises in general. The move to fiat money made explicit the political foundations of money, enabling central banks to respond to economic crises and enhancing the circulation of credit in the economy. As with trade unions, central banks help to coordinate economic decision-making so as to prevent panics and unnecessary credit crunches. Both trade unions and central banks are non-market coordinating institutions that blur the lines between the state and the market. They are not captured well by the opposition between state and market or regulated and unregulated markets. They play a crucial role in the economy, but they are often shielded from direct democratic scrutiny and control. Yet with the rise of institutions like labor unions and central banking, Polanyi saw the first glimpse of an alternate political order to the market society, one that would subordinate the major centers of economic power to ongoing democratic accountability and control.

Rethinking Debt and Democracy

The midcentury welfare state, then, embodied an effort to reconcile capitalism with the democratic potential of both the labor movement and the non-market management of money and credit. Yet this era of partial economic democracy was short lived. In retrospect, we can see that the midcentury welfare state settlement was built in a permissive institutional context. Postwar growth and the persistence of exploitative relationships between colonial powers and their former colonies all helped to reconcile business to powerful trade unions and active central banks. But beginning in the late 1960s, cracks began to show in the postwar settlement.

The story of the breakdown of the mid-century settlement has been told many times. Amidst persistent inflation due to uncoordinated wage demands and external shocks, the defenders of the market system advanced a new gospel of central bank independence. But less often noted is that the decline of social democracy has coincided with the rise of the politics of debt. Easy access to consumer credit became what sociologist Colin Crouch calls “privatized Keynesianism,” a way to sustain economic demand without direct fiscal stimulus. In the United States, rising asset values—above all, in real estate—compensated for stagnant wages and weak retirement systems.

The rise of debt has transformed democracy. Political cleavages are being redefined around debtor–creditor relationships, both domestic and international, as well as by the politics of asset values and real estate. The increasing reliance on debt to finance government expenditures would tilt political power away from democratic constituencies and towards bond markets, which have taken on a totemic power. Finally, these shifts led to the growing power of central banks as the guardians of the economy, raising fundamental questions for democracy: Are central bankers neutral technocrats realizing preset policy goals, or do they have to balance, even if unknowingly, competing interests and values? If the latter, how should banking systems be organized to ensure fairness and transparency? In the United States, this could mean ensuring representation from different groups in society in the Federal Reserve System, such as labor unions. Or it could mean rethinking the overriding focus on price stability and so reviving better cooperation between fiscal and monetary policy in the context of persistent low inflation.

The increasing reliance on debt to finance government expenditures would tilt political power away from democratic constituencies and towards bond markets, which have taken on a totemic power.

Recognizing the political foundations of money also raises questions about the right to access credit and benefit from national banking systems. Ultimately, the credit-making function of central banks rests on the future security provided by democratic institutions. Indeed, part of the rise of central banking was to enable states to borrow for military conflict, using future tax revenues—and so ultimately political legitimacy—as collateral. Citizens of a country are collectively responsible for their liabilities, but often without a reciprocal right to access the benefits of an extensive credit system on equal terms. Rather, they are subject to sometimes harsh and unaccountable credit evaluation regimes that emphasize the rights of creditors rather than debtors. A full normative theory of the right to credit would have to balance concerns about moral hazard against the distributive benefits of expanding credit. But the foundation for such a right comes from the political and democratic basis of credit-creation in the economy as a whole.

Globalization or Cooperation?

Brexit and Trump—the revolt against globalization in defense of the historical fantasy of national sovereignty. Today, it sometimes seems that the only alternatives to market-driven globalization are various versions of authoritarian nationalism. And without a doubt, nationalism is the dark underbelly of arguments for economic citizenship. Does a return to an ideal of economic democracy, as described by Polanyi, mean a retreat back towards relatively closed society? Certainly, proximity aids the functioning of coordinating institutions by making it easier to shame non-cooperators—one of the benefits of embedding them at the national level. Equally, though, economic democracy requires international cooperation.

Instead of such cooperation, though, global integration has largely proceeded through market making, opening up national markets to foreign investment and global capital flows. Behind this form of globalization is skepticism towards democracy. Democratic institutions produce protectionism, rent-seeking, and constraints on the ability of states to enact regulations. Other “non-tariff barriers to trade” are justified by the additional economic growth market integration will produce. In contrast, reciprocal cooperation accepts the legitimacy of democratically created restrictions on the market and non-market institutions but searches for global institutions to ensure that the democratic systems take into account the interests of non-members.

The European Union exemplifies both reciprocal cooperation and market-driven globalization. The project of integration was born of a desire to substitute cooperation for conflict within a continent where no state was large enough to exercise hegemony. Over time, however, the single market has become the telos of integration, as the European Court of Justice and the European Commission have become increasingly willing to subject domestic economic systems to supervision in order to perfect the single market. Restrictions on national governments would be justified by the economic growth unleashed by the single market. Yet again, debt interrupted this vision of smooth market integration. The contradiction between reciprocal cooperation and market-integration exploded during the Eurozone debt crisis. And it exploded because the architecture of the European Monetary Union failed to take seriously the complexities of money. The Euro immensely facilitated market integration. But it also separated out money from debt, as national central banks remained responsible for issuing bonds tied to national governments.

The contradiction between reciprocal cooperation and market-integration exploded during the Eurozone debt crisis.

The Eurozone crisis thus set up a remarkable clash between the principle of cooperation and the principle of market-making—with the latter winning the day. In the landmark Pringle and Gauweiler rulings, the European Court of Justice found that the extraordinary efforts by the European Central Bank to counter market panics by potentially buying government bonds did not violate the non-bailout clauses of the EU treaties. But this was because such bailouts came with harsh forms of conditionality and direct political supervision—conditionality that overrode domestic democratic legitimacy. Conditionality meant the internal reorganization of debtor economies in line with the demands of the single market. Reciprocal cooperation between national governments gave way to the demands of the single market, as debtor countries were compelled to reorganize their internal economies to increase the scope of market forces—or face the prospect of crashing out of the Eurozone.

Conclusion

The organized working class built social democracy in Europe and, to a lesser extent, North America, in an era of rapid industrialization and democratization. In creating institutions to disconnect the value of labor from the demands of the market, social democracy constructed a new ideal of social citizenship. But what does citizenship, social or otherwise, mean in an era of debt and finance? How can democratic ideals assert themselves in the face of independent central banks and globalized financial markets?

While far from exhaustively answering these questions, Karl Polanyi provides one of the most incisive analyses of the tension between capitalism and the non-market institutional structures that channel democratic demands and ideals into economic production and exchange. He helps us see how the conflicts within capitalism are defined, not just by the confrontation between labor and capital, but also by the politics of money and conflicts between debtors and creditors. And he envisions a path beyond the deadlock between market openness and nationalist closure. In the face of resurgent authoritarian nationalism, democrats and liberals can rescue the principle of international cooperation between democratic communities—but only if we lay to rest the fantasy of the market society.

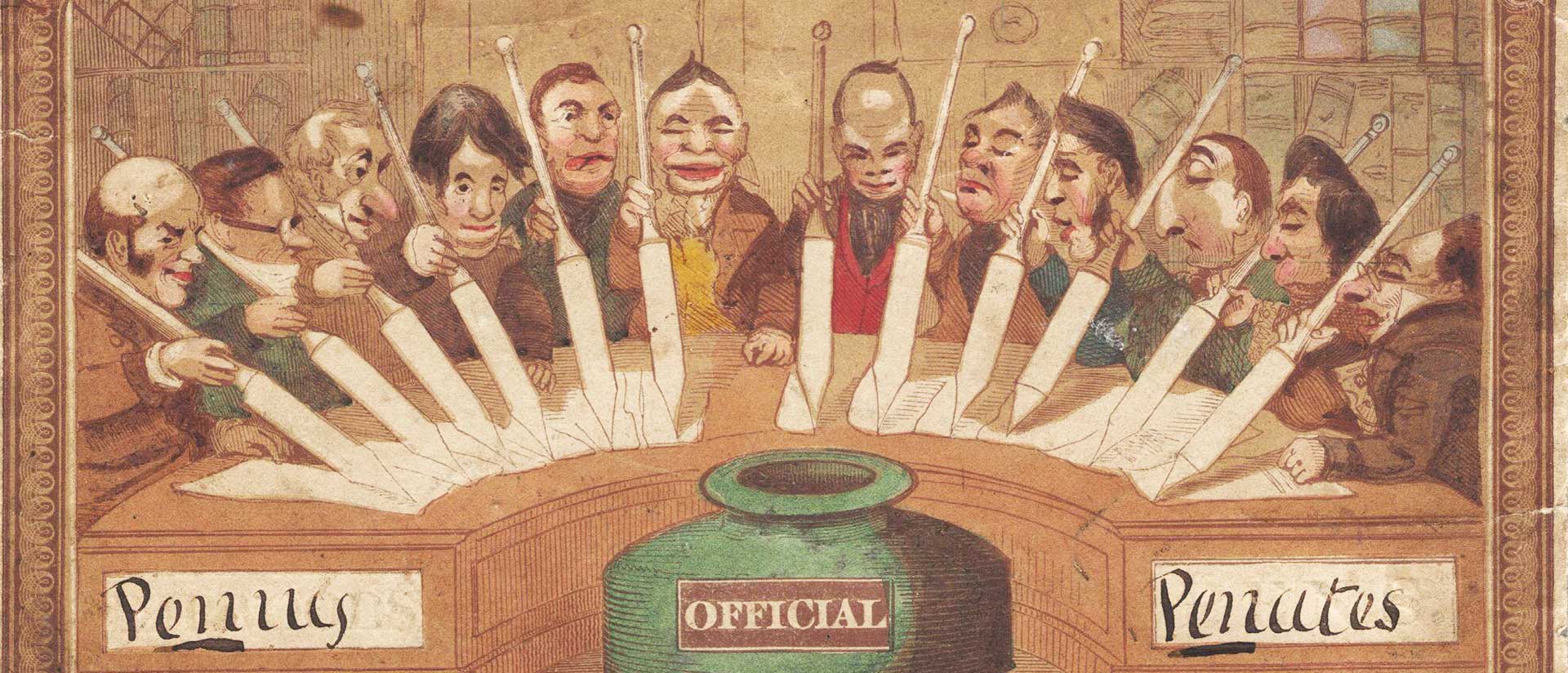

Caricature of Karl Polanyi by R. Jay Magill, Jr., originally for The American Interest. Reprinted with permission.