Wish You Were Here!

A brief history of the postal card

By Liliane Weissberg

The postcard is a rectangular piece of sturdy paper and often bears a printed picture. It has many predecessors: the illustrated broadsheet, playing card, advertising notices, visiting card, or, simply, stationery stamped or engraved with images. But it’s fair to say that the postcard proper could not have come into existence without the invention of the postal stamp.

The first issue of the penny stamp, in Great Britain, in 1840, marked a change in the entire economic system of correspondence. Previously, mail was paid for by the recipient of a missive, not the sender, and while the cost of mail depended on the number of letter sheets used, it was largely calculated in reference to the individual mail-service employed and the distance a letter had to traverse. The postal stamp brought radical change: mail was now paid for up front, and the calculation of distance for delivery was largely replaced by another measurement: weight.

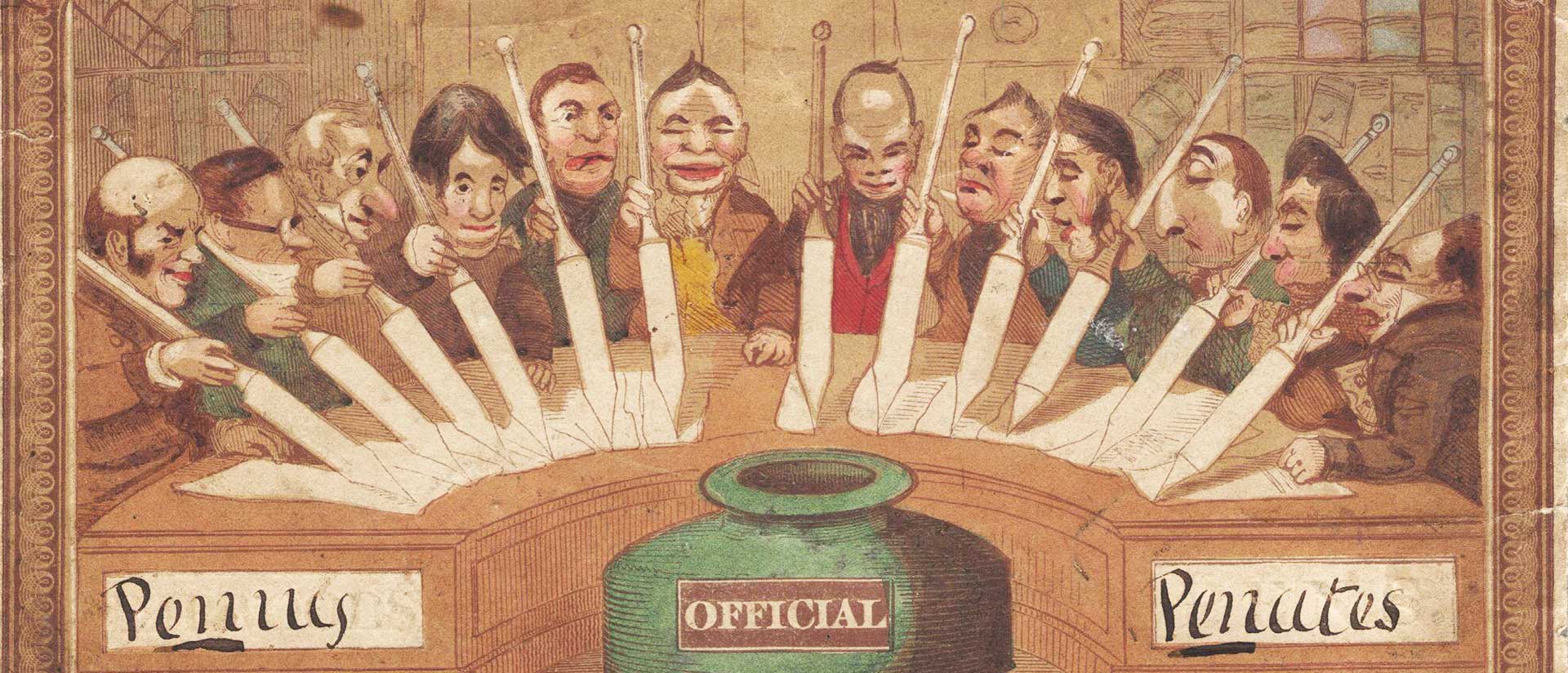

At first, the concept of stamping was not limited to a small square of paper to be affixed on the corner of an envelope; it involved the entire envelope. William Mulready, an artist and member of the British Royal Academy, won a competition for the design of an official postal envelope itself. The design showed Britannia front and upper center, surrounded by symbols of imperial power that referred not only to current colonies but also to colonies of the past. William Penn is pictured on the upper right margin of the envelope, in conversation with Native Americans. Criticism of Mulready’s design was voiced as soon as the envelope was published, discussed in the London Times and elsewhere. Competing, privately published envelopes were also issued. They pictured caricatures of Britannia, flying scribes, and a donkey instead of a lion. These images were discussed publicly as well; there was also the question whether such privately issued envelopes should or could enjoy the services of the British Royal Mail.

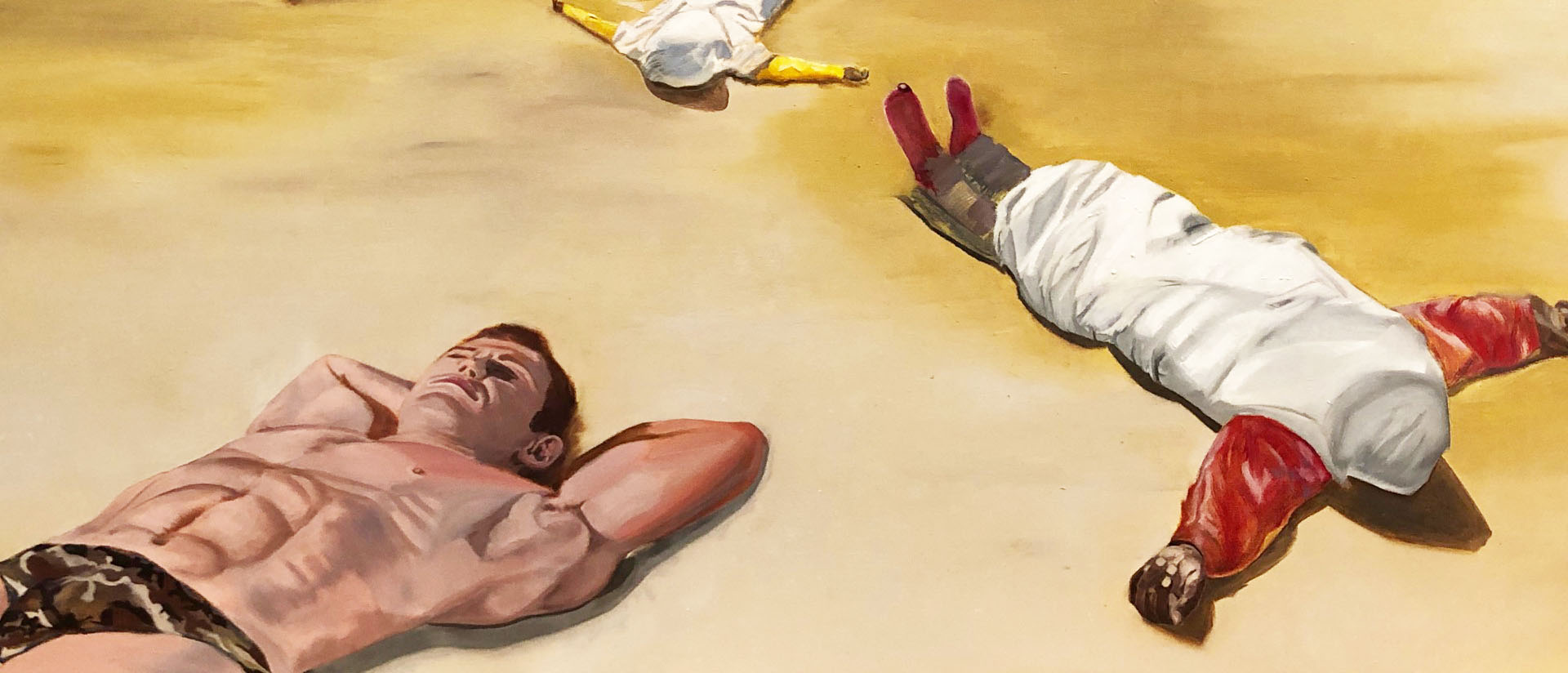

But it is another piece of mail that should elicit our rapt attention. In July 1840, a simple piece of paper, addressed to “Theodore Hook,” was graced with the new black penny-stamp and dropped into the London mail. It is the first postal card to be mailed (that we know of). On the back of the sheet, there was a hand-drawn image: a caricature of postal workers eagerly dealing with the new envelopes and stamps. The address of the sender was not given, but it can be assumed that it was no other than the recipient of the card himself, the novelist and playwright Theodore Hook, who was always ready for a good hoax. The intended viewer of this missive was therefore not the recipient of the mail; the intended viewer was the postal workers who had to sort and deliver it. In this sense, Hook was aware of a new and important transformation: in contrast to a letter inside an envelope, this piece of mail had no envelope to conceal the sender’s private note. Its message, instead, was public. Hook’s postcard acknowledged this novelty.

When the Prussian postal official Heinrich von Stephan proposed the introduction of an open “postal sheet,” or Postblatt, to the Northern German Postal Federation 25 years later, in 1865, he could cite many reasons that would recommend its adoption: the postal sheet was light and therefore economical, and it was thought to limit the flood of mail. Letter writing would be faster, too, and an emphasis on speed was important in a time of technological progress and industrial revolution. He also hoped that the limited space would promote a more concentrated style of writing. Moreover, the postal sheet was meant to compete with the telegraph system, by offering a cheaper, and hence more democratic, means of communication. In all of this, the postal sheet was modern. Von Stephan argued in his application:

The form of the letter, like many other human contrivances, has, in the course of time, undergone numerous modifications. In antiquity, the wax tablets that contained the writing were united by rings; the letter was, so to speak, a book. Then came the form of the roll, which lasted until the Middle Ages. Later still, the letter assumed a more convenient form and was sent folded up, and ultimately, the envelope came into use […] From these various changes, the form became ever more and more simple. This is equally true of the contents, as is shown by the extreme pomposity of the earlier epistolary style, with its formal repetition of titles, etc.

Von Stephan’s sketch of the evolution of the letter points to a straightforward development from the wax tablet to the new postal sheet. And this most novel format would have “the dimensions of ordinary envelopes of the larger size and consist of stiff paper, corresponding therefore in size and quality to the recently introduced Money Orders used in some of the German postal districts.”

Unfortunately, von Stephan’s proposal was not met with success; the new type of money order failed to satisfy the Postal Federation’s economic calculations. Publicly, however, they offered a different reason: the postal sheet failed to maintain the mail service’s standard of privacy. In newly bourgeois nineteenth-century German society, private and public realms were carefully separated; messages that could be viewed by postal employees, servants, or other external readers were seen to violate this separation.

In newly bourgeois nineteenth-century German society, private and public realms were carefully separated; messages that could be viewed by postal employees, servants, or other external readers were seen to violate this separation.

With the German effort roundly rejected, the Austro-Hungarian Empire pressed forward, becoming the first state to approve the postcard for official mail delivery, in 1869. This time, the proposal had been issued by an economist, Emmanuel Hermann, for whom the calculations did make sense (Hermann has been celebrated ever since as the inventor of the postcard). A British business journal of the day reported:

The Austrian government has introduced a novelty in postage which might be introduced with great benefit in all countries. The object is to enable persons to send off, with the least possible trouble, messages of small importance, without the trouble of obtaining paper, pens, and envelopes. Cards of a fixed size are sold at all the post-offices for two Kreutzers, one side being for the address and the other for this note, which may be written either with ink or with any kind of pencil. It is thrown into the box, and delivered without envelopes. A halfpenny post of this kind would certainly be very convenient, especially in large towns, and a man of business carrying a few such cards in his pocket-book would find them very useful. There is an additional advantage attaching to the card, namely, that of having the address and postmark inseparably fixed to the note.

The sender’s address was not to be included. Instructions were formulated to protect mail recipients as well as postal workers from offense. (For a while, six rules for postcard writing were printed on the bottom of each card.)

The correspondence card elicited additional concerns: in contrast to von Stephan’s predictions, people feared that it would lead to a deterioration of writing style and a decline in epistolary decorum. And if the cards could not assure privacy, were women allowed to use them? Did cards have to be distinguished in size and color to mark the gender of the correspondent, as had been previously done with the color of letter seals? In the years following 1870—the year Germany’s postal system, under von Stephan, officially introduced the postcard in the country’s north—books of etiquette focused on questions of postcard decorum and social class: Was one allowed to write cards to persons of a higher or of lower social standing than the author? Was the card too cheap a medium to be used by the upper class? Many of these questions and concerns subsided when Queen Victoria herself pronounced her personal interest in postcards.

Once private companies began to issue these cards, they became increasingly decorated with images, turning the postal sheet or correspondence card into a picture postcard. Most of these are known as “view cards” and show geographical locations; advertisements or greetings cards also appeared. The early postcards kept the separation between the address side, on the front, and message side, on the back; they had to thus combine image and text on one side. The text was to be inscribed by hand under, or next to, the image; text and image were to be read and viewed together. New printing technologies made this possible, and German publishers were ahead of the pack. Lithography as Steindruck was further developed specifically for this purpose, and Germany soon emerged as a lead publisher. The old centers of book publication, primarily Leipzig, became hubs of postcard production, exporting their innovative wares throughout Europe and to America and African colonies.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 helped to increase the popularity of the postcard. For the delivery of mail during wartime, weight became all important. The French mail service even experimented with delivery via balloons. Preprinted cards would also be issued and distributed to soldiers on the front, which assured both speedy notices for soldiers—and easy censorship for superiors. All a soldier had to do was to check whether they were healthy or not, whether they felt well or not, and send it on, like a questionnaire.

Preprinted cards would also be issued and distributed to soldiers on the front, which assured both speedy notices for soldiers—and easy censorship for superiors.

Germany became Germany, of course—i.e. the German Reich—after the Franco-German War. View cards became crucial in promoting the national project, acquainting the German population with the newly imperial sites, particularly its new capital, Berlin. British or French citizens were informed about colonial territories mostly via postcards printed by German publishers.

And then, of course, there was the rise of the tourist industry, with which the phenomenon of the postcard would become intimately linked. Between 1895 and 1920, during the so-called Golden Age of the Postcard, almost three-hundred billion postcards were mailed worldwide. Germans were by far the most avid users of the medium, forwarding view cards of local sites and places encountered on travels, as well as cards for holidays or special occasions. Moreover, collectors not only wrote on postcards, they also bought them as souvenirs and for inclusion in albums. Postcards could even be stamped at post offices for dating purposes only, without putting them in the mail—a popular practice that lent evidence of one’s travels.

By 1907, an important physical change would take hold: the postal office would permit the printing of divided address sides. Now, the postcard could truly transform from a correspondence card into a picture postcard, with an entire side dedicated to the image. Photographs, framed at first in white margins, began to adorn the cards. People began to collect them with vigor—not for the messages, which became increasingly secondary, but for the images themselves. Postcards offered cheap reproductions of pictures that were, in turn, standard size, and could thus be placed into photo albums. At first, postcard collecting was viewed as an occupation for women and girls, but the industry sought to change this, introducing specific sub-genres of picture cards featuring political caricatures, pictures of popular actresses, or scarcely clad women.

Photographs, framed at first in white margins, began to adorn the cards. People began to collect them with vigor—not for the messages, which became increasingly secondary, but for the images themselves.

Germany’s dominance in the postcard market ended with WWI. Mail services were restricted, and wartime was an obvious set-back for tourist travel. But it was Germany’s final defeat in the Great War, perhaps more so than the use of new print technologies, that put an end to the country’s postcard reign. Companies in the United States, England, and France were on the rise.

And then, et voilà: Paris became the capital of the postcard. The 1889 World Exhibition there marked the centennial anniversary of the French Revolution, showcasing new inventions, people, and objects from places all across the world. It also offered a three- hundred-meter steel-and-iron construction that would become the symbol of a new time. While the Eiffel Tower loomed above the fairgrounds, one could also enter the newly invented elevator to ascend to three separate viewing platforms. On the two lower ones, visitors could find restaurants and shops, including ones that sold postcards. On the top level, a postmaster was conveniently seated at his desk, eager to stamp visitors’ purchases and mail them off.

The Eiffel Tower was the grandest post office of all, and it was dedicated to the medium of the postcard. In exchange for its spotlight, the Eiffel Tower became the postcard’s most popular motif. But something else was to happen: tourists who climbed the Eiffel Tower not only viewed the intricate steel construction, they also saw the city of Paris itself—its wide avenues, marvelous geometry, and bustling pedestrian life. A reversal was underway: the world exhibit used the Eiffel Tower, and the Eiffel Tower turned Paris itself into a grand exhibition space.

Postcard publishers were quick to take advantage. At the time of the World Exhibition and throughout the following decades, postcard printers hired illustrators, and soon photographers, to capture the views from above. They documented Notre Dame and the streets of Paris, leaving out a couple of arondissements—those of the very poor, and some of the very wealthy. Photographers like Yvon (Pierre Yves-Petit) photographed sites from above, climbing on roof tops and ledges; Eugène Atget took photographs in the street, documenting empty sidewalks and shop windows alive with consumable things. It was a mapping project of enormous proportions. Parisian picture postcards were published in series, so that consumers could acquire a panorama of the city that could be arranged and rearranged in personal photo albums. These postcard images turned Paris into an icon of modernity. They also launched the postcard’s career as its own exhibition space—and as a city’s best advertising agent.

Image: Detail of backside of the “Theodor Hook, Esq.” postcard. Courtesy Eugene Gomberg.