No Refuge

Burning the Mediterranean Sea

By Hakim Abderrezak

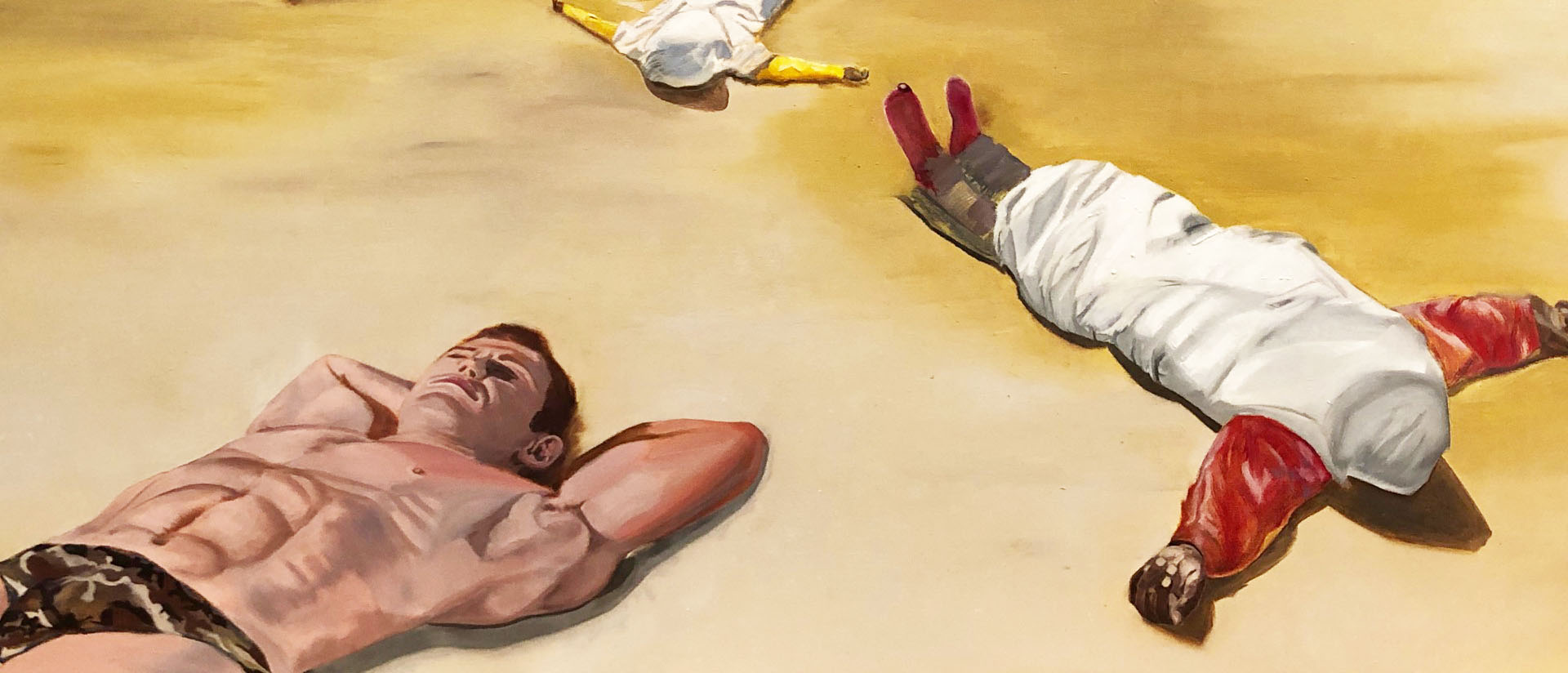

Throughout my childhood, my family would travel to Morocco, where my mother was born. The six of us would make the multi-day journey by car from Normandy, crossing much of France and all of Spain. One August, on our return to France, I witnessed a scene that has stayed with me to this day. As I later came to realize, it would influence both my scholarship, which in 2008 began to focus on clandestine migration, and, more recently, my own artwork about unauthorized sea crossings.

One night at the port of Melilla, a Spanish enclave in Morocco, car drivers were directed to park in straight lines in preparation for passport inspection and vehicle searches. While Spanish officers were checking ferry-boarding passes and examining passports, agents had their dogs circle cars and vans and encouraged them to jump inside if they became more animated than usual.

The people in front of us were next in line for the security check. I saw the security dog become very excited. The officer asked all of the passengers to get out of the vehicle. The compact car was packed with suitcases, blankets, clothes, souvenirs, and many other objects. Standing by, the family looked distressed as the dog kept sniffing a bag located under the back seat. The family had not only stuffed their belongings on top of the vehicle and in the trunk; they also filled the space between the front and back seats—a common practice among Moroccan families to maximize space and make it more comfortable for the children to sleep. That small space, however, also contained a teenage boy, who obviously had been instructed to remain hidden until onboard the ferry. He never crossed over the Spanish border. I remember searching for that family on the ferry, but I never found them. Maybe they were all detained. Maybe the teenager became one of the many migrants who tried to cross the Mediterranean Sea on fishing boats in the 1990s. I will never know; I will always remember.

Before incidents like this made it into the international news in recent years—or, rather, before tragedies that had been transpiring for decades were deemed as such and then lumped into what has since been termed “the refugee crisis”—capsized boats were covered by local news, mostly Andalusian networks that reported on captured migrants and corpses washed ashore. For several decades now, literature—among other forms of representation—has also addressed the topic of Mediterranean migration. Since 2009, when I first published about the tragic crossings taking place in the Mediterranean, I have called this body of literary works illiterature.

This neologism teases out three major features in fictional accounts onthe topic. First, the novels, novellas, and testimonies, written in various languages, feature characters who are “ill” before, during, and/or after their sought maritime passage. Second, this literary subgenre has been dominated by male writers (“il” is the masculine personal pronoun in French). Third, in these stories—many of which were written by North African writers in the French language—the Global South is portrayed as an island (“ile” in French) that must— along with its inhabitants—be kept at bay at all cost.

“Illiterature” is primarily concerned with the idea of the Mediterranean Sea as an impediment to northward travel. Illustrative titles include Mahi Binebine’s Welcome to Paradise (2004), Laila Lalami’s Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits (2005), Youssouf Amine Elalamy’s Sea Drinkers (2008), and Laurent Gaude’s Eldorado (2008). The perilous crossing is undertaken by individuals who, in other media, are often dehumanized and depicted as threatening masses, hordes, and invaders. This literary category comprises alternative narratives that attempt to address and redress erroneous conceptions and to raise awareness of refugees’ plight. For example, representatives of illiterature such as Tahar Ben Jelloun’s Leaving Tangier (2009) have brought attention to the existence of sophisticated technology used to screen and sieve Global

South citizens and their movements. With a focus on individual characters, illiterature makes concrete the human lives that suffer; it voices a humane way of understanding those lives in order to denounce the dehumanizing and desensitizing numbers that flash across our television screens. Unlike the news, fiction tells us about the dream shared by refugees to make the discriminating sea disappear— either behind them (in the case of a successful crossing) or in front of their eyes (in the case of a highly coveted and impossible passage).

Unlike the news, fiction tells us about the dream shared by refugees to make the discriminating sea disappear.

While the above novels and novella—as well as the accounts comprising the book Tu ne traverseras pas le detroit (2001)—deal primarily with the crossing of the Strait of Gibraltar, separating Morocco from Spain by a mere 14 kilometers, the more recent corpus has dealt with different lands and islands, and other straits, stretching out eastward to the Strait of Sicily,

Tunisia, Lampedusa, Lesbos, Turkey, and more. The widespread goal of reaching Europe by sea has been treated in a variety of creative mediums since before the beginning of the century, as exemplified by Maati Kabbal’s short story “Patera Express” (1999). The often-deadly endeavor has also appeared in films by directors hailing from a variety of Mediterranean countries, including Nabil Ayouch’s Mektoub (1997), Mohsen Melliti’s Io, l’altro (2007), Chus Gutierrez’s Return to Hansala (2008), and Merzak Allouache’s Harragas (2009). Music, too, has commented on the tragic topic. For instance, in the track entitled “El Harraga” (2012), the iconic Algerian rai singer Khaled sings about a father who mourns the drowning of his two young sons. A wide artistic realm, including fine art and other domains, has collectively reflected the aspiration of a growing number of individuals and characters to “burn away” the immense body of water in their way. Literature, film, music, and visual art have all conveyed characters’ longing to dispel the deceiving idea (and deceptive ideal) that the Mediterranean is a sea for all. It is instead a sea that has interrupted travel for many and permitted free movement for a few.

The desire of refugees to change their conditions is encapsulated in the term that many migrants and refugees employ to refer to themselves: harragas. This Arabic word means “burners,” derived from the Arabic hrig or hriq (“fire”). Originating in North Africa, the designation applies to migrants and refugees alike in that it names individuals (in real life) and characters (in works of fiction) who share similar modes of travel (clandestine), means of transportation (boats), itinerary (the Mediterranean Sea), place of origin (Global South), destination (Europe), and pull and push factors (which, contrary to widespread belief, are not limited to lack of economic opportunity, and may include denial of fundamental rights, which also affect those labeled as “economic migrants”).

In the context of furtive trans-Mediterranean migration, “burning” is mainly explained as an action— namely, harragas literally burning their identification papers to prevent deportation to their countries of origin. Moreover, in Arabic, one either “burns” or “cuts” the sea rather than simply “crosses” it, as in English. In other European languages, transiting the sea also invokes smooth passage: uberqueren in German, traverser in French, atraversar in Spanish, atravessar in Portuguese, and attraversare in Italian. But “burning” must also be understood in its allegorical sense: it is a kind of intense wishful thinking— “a burning desire”—a doing away with a sea-obstacle that obstructs people’s right to migrate.

In Arabic, one either “burns” or “cuts” the sea rather than simply “crosses” it, as in English.

In this way, the Arabic language reveals how the Mediterranean has long been conceived as a barrier requiring strong means for getting past or over it. Though the idea of “cutting” the sea did not necessarily connote clandestineness a few decades ago, today the language indicates that if one must “cut” the sea, it is because the Mediterranean is not associated with fluidity and motion but rather with rigidity and immobility. Burned down to its bed, the Mediterranean basin could be traversed by walking over it, rather than forcing migrants and refugees to “burn” or “cut” it.

The term “burners” in Arabic also crystallizes a vision of the world, from the point of view of human beings who consider their leave-taking to be legal, ethical, and essential, rather than criminal. Their forced passage symbolically advocates for rights, and it highlights wrongdoing. To call harragas and their acts of migration “illegal” is a problematic misrepresentation; it implies criminalization, regardless of the legality of refugees’ movements as acknowledged in international law, which nations have signed and vowed to uphold—but, more often than not, hold up instead.

In our reckoning of maritime tragedies, it is important that we abstain from characterizations like this, to avoid reproducing improper and potentially unethical narratives. It is similarly important to retain harragas’ own terms (or at minimum to be conscious of their existence and meanings) in order to better grasp their plight. When discussing a phenomenon specific to a society expressing itself and acting through specific languages, religious obligations, regional traditions, cultural impetuses, and so on, generic terms can easily minimize and distort the ordeal of those living through it.

This is all to say that in order for us to better comprehend why and how the “refugee crisis” has come to be, we must include Southern perspectives in our thinking and research. This implies fully acknowledging the “objects” of discourse as the subjects of their own history, endowed with their own side of the story. This entails lending our ears and giving voice to Global South citizens—both of the harragas and those residing on the southern and eastern rims of the Mediterranean, who have been overlooked or silenced altogether. Their perspective, cognizant of noteworthy regional idiosyncrasies (linguistic, cultural, societal, religious, historic, political, geopolitical) is central in piecing together a fuller picture of what migration means and why it happens. In so doing, local vocabulary is preferable to administrative or political terminology. And neologisms can be useful for teasing out the implications embedded in a native vernacular. These tools are crucial in lending nuance to a hegemonic (or, perhaps more aptly, hegemaniac) discourse—a narrative long obsessed with its own supremacy.

In 2015, the expression “refugee crisis”—a misnomer—became the official way of naming something that had been happening for decades. One of the implications of this deceptive appellation is that the crisis is intrinsically European, despite the fact that the impact of forced migration has struck hardest in West Asian nations—most notably Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan, who have taken in the greatest number of refugees. The mass movement of people across the Mediterranean was deemed a “crisis” when it began to take place in large numbers and in a more frequent fashion, forcing Europe to worry about its handling of the situation, in addition to its own future and responsibilities.

This worry was first sown in December 2010, when the Jasmine Revolution occurred in Tunisia, paving the way for the Arab Spring, which then unfolded over the years that followed. The Jasmine Revolution is thus still tightly linked to the “refugee crisis,” because social unrest in North Africa spurred thousands of people to set off to sea in the hopes of reaching calmer shores on the other side, southern Europe.

Seen this way, recent migration across the Mediterranean began as a form of rebellion, which must be understood both literarily and metaphorically. Migration is an act of activism, a personal struggle undertaken collectively, oftentimes within a community of strangers embarking on the same boat, trying to rise up from a low status in various spheres of life (economic, societal, political) and amid mediatized depictions of harragas as ill-intentioned evildoers, ranging from dangerous criminals to potential terrorists. Modern-day exilic endeavors from Africa, the Levant, and the Middle East have led to what might be called a “downrising”—European officials downplaying the dangers migrants and refugees face and questioning their reasons for leaving. Downrising aims to make asylum-seekers ineligible for rescue and refuge.

Migration is an act of activism, a personal struggle undertaken collectively, oftentimes within a community of strangers embarking on the same boat.

In the end, tragedies, uprisings, and unrest go down in history. But will the untold stories of the uncountable number of anonymous individuals who drowned in the Mediterranean make it into collective history? To remember the heroic deceased, one must re-member their bodies that have been dismembered by electronic nets and hungry fish; one must pay homage to their memories for losing their lives while seeking safety and shelter in times of danger, persecution, or war at home. To re-member, we need memorials, for when a nation does not memorialize, citizens do not memorize what must be learned from past mistakes. Struck by a tragic end, migrants and refugees do not leave behind memoirs; they leave only memories maintained by others. Memorials thus serve as alternatives to missing personal narratives.

To write, film, sing, and paint today about migrants departed under the sea is a form of popular memorial. Fictional and artistic memorials have proliferated in the quasi-absence of institutional memorials that honor the memory of burners and acknowledge the deadly character of a phenomenon with global repercussions. The scarcity of such memorials is all the more surprising as the phenomenon of Mediterranean crossing has been occurring for decades. Politicians have thus had ample time to “officialize” their nations’ mourning of those who sought their aid. Instead of creating this kind of memorialization, however, the European Union in 2018 began forbidding NGO ships from rescuing drowning men, women, and children at sea. It also began enabling law enforcement to use oppressive and repressive methods against refugees trying to set foot on European soil. These measures and the silence of the thousands of dead harragas have turned the Mediterranean into the world’s largest maritime cemetery—a seametery.

Image: Hakim Abderrezak, Unflappable (detail), 2018, oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches.