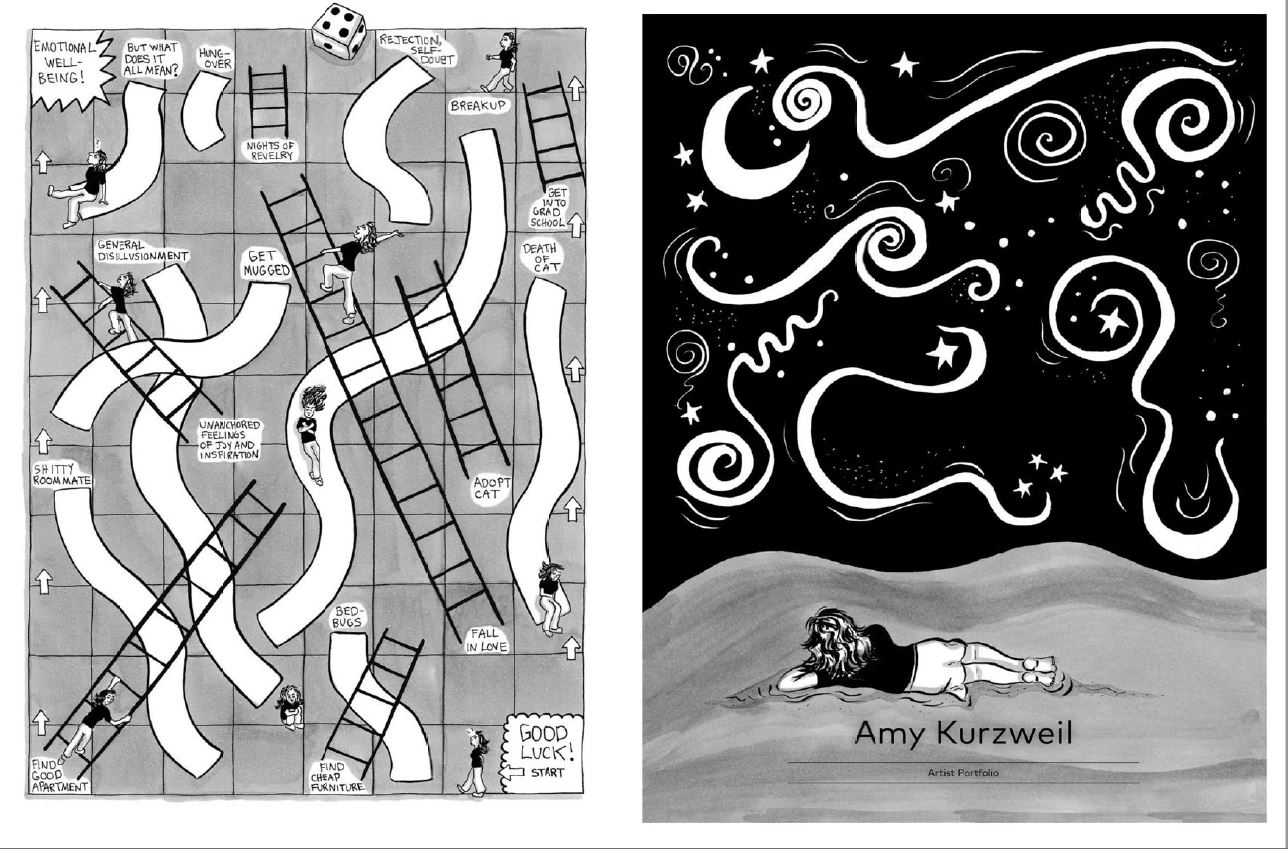

Artist Portfolio: Amy Kurzweil

Hyper-Specific Observations

By Emma Allen

There’s a line from Amy Kurzweil’s graphic memoir Flying Couch that’s been running through my head throughout the pandemic. The book is about three generations of women—as much about her grandmother’s harrowing escape from the Warsaw Ghetto and Amy’s sometimes tense but always tender relationship with her psychotherapist mother as it is about Amy herself. At one point in the memoir, Amy is traveling with her mom, feuding about something insignificant, mulling the gaps in her family tree—erasures of war. “I wonder if shorter roots are thicker roots,” Amy writes. “Thicker roots have more knots and snarls.” At a time when we’re all either cooped up, tripping over our connective roots, or finding ourselves separated by a gaping vastness (Zoom notwithstanding), this image feels particularly poignant. As I bicker with my own mother (with whom I’ve been quarantining for five months), I think about Amy’s musing: “I never know exactly what we’re fighting about, but it usually has something to do with leaving each other.” We are living in a moment of too-closeness, too-farness, and never-ending anxiety about potential loss, or losses already accrued, but, as Amy eloquently puts it, “Humor is mortar. It binds the bridge between the real and the unimaginable.”

Thank god for humor. My uniquely odd job as Cartoon Editor of the New Yorker these days is to review a constant deluge of jokes about the end of the world, certainly as we know it. But, as Amy so wonderfully illustrates time and again, we make jokes not just to sublimate pain or to keep reality at bay, but because sometimes terrible things are absurd things—just pick up any American newspaper for confirmation. And the ways in which we survive impossible situations can make fools of us, the only sane response to which is to laugh.

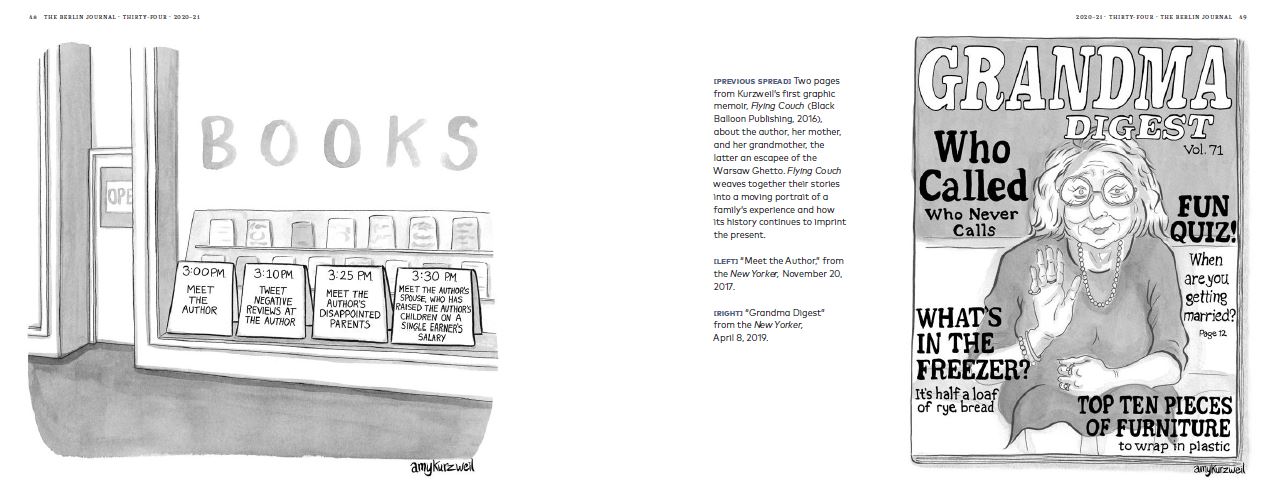

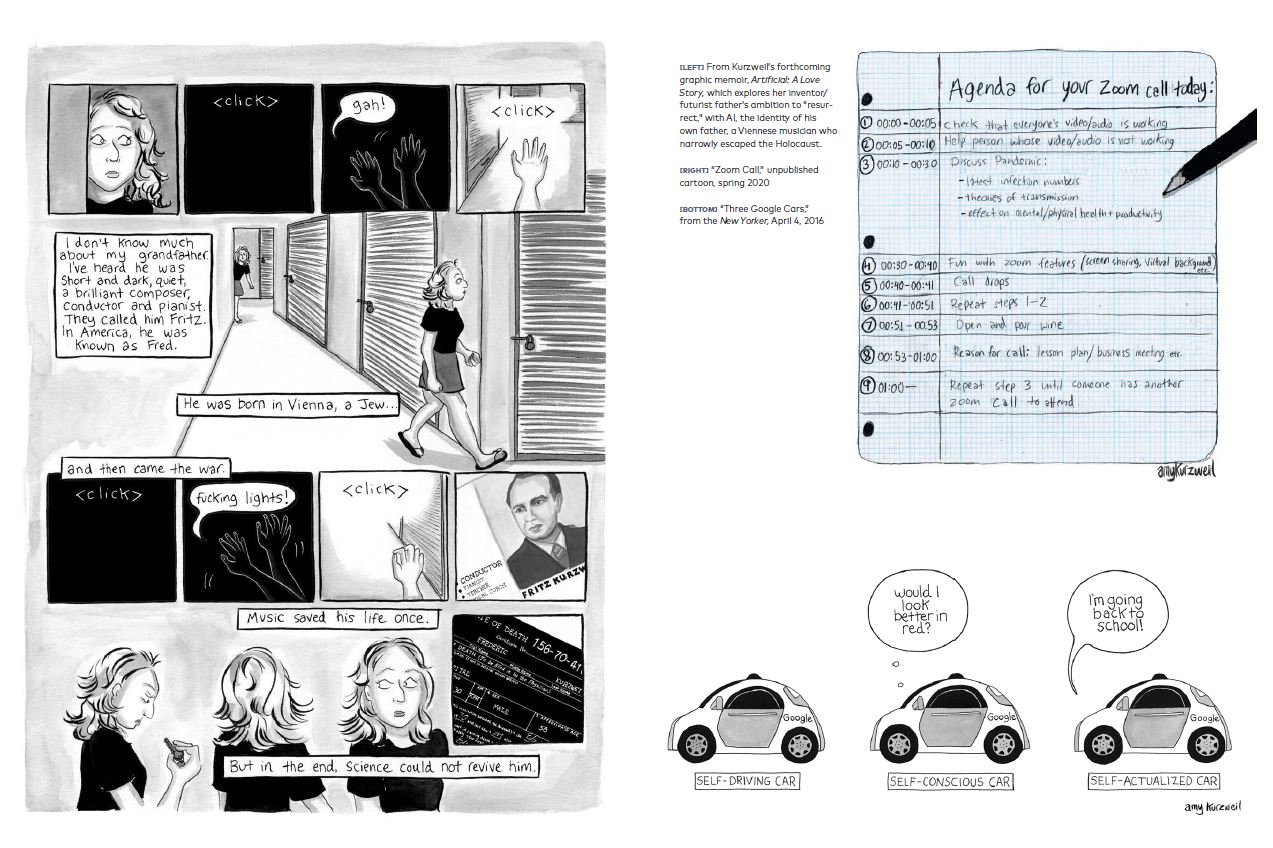

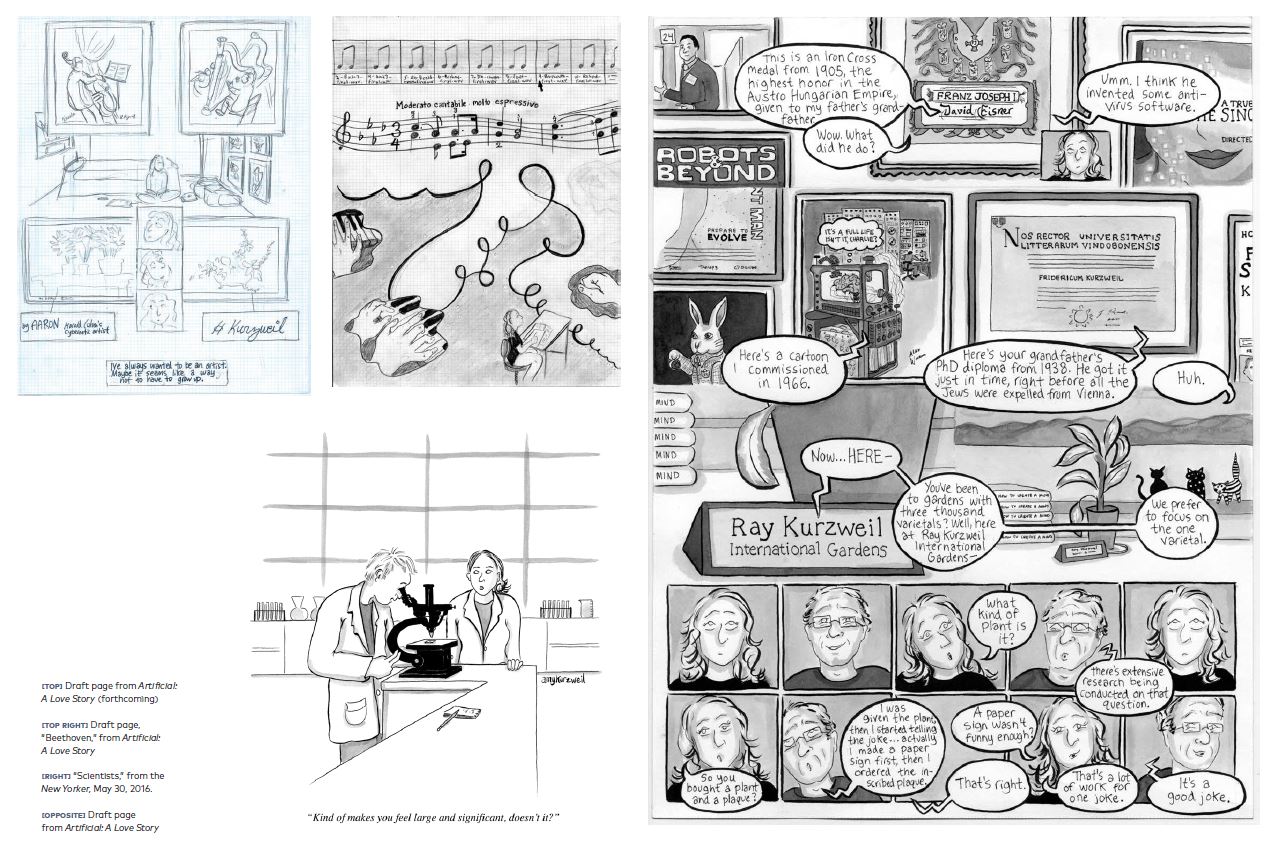

Amy explores how trauma manifests over generations, not just through historical data points but through the most minute details of how we live. And that’s what single-panel, New Yorker cartoons are—hyper- specific observations and juxtapositions concisely conveyed that reveal something greater than their parts. Take, for instance, one cartoon of Amy’s that features the cover of an imaginary magazine called “Grandma Digest” which teases such deliciously specific articles as, “Who Called/ Who Never Calls,” “Fun Quiz!/ When are you getting married?”, “What’s in the Freezer/ It’s half a loaf of rye bread,” and “Top Ten Pieces of Furniture/ to wrap in plastic.” From the micro, we infer the macro. As Amy puts it in another cartoon depicting two scientists, one looking into a microscope: “Kind of makes you feel large and significant, doesn’t it?”

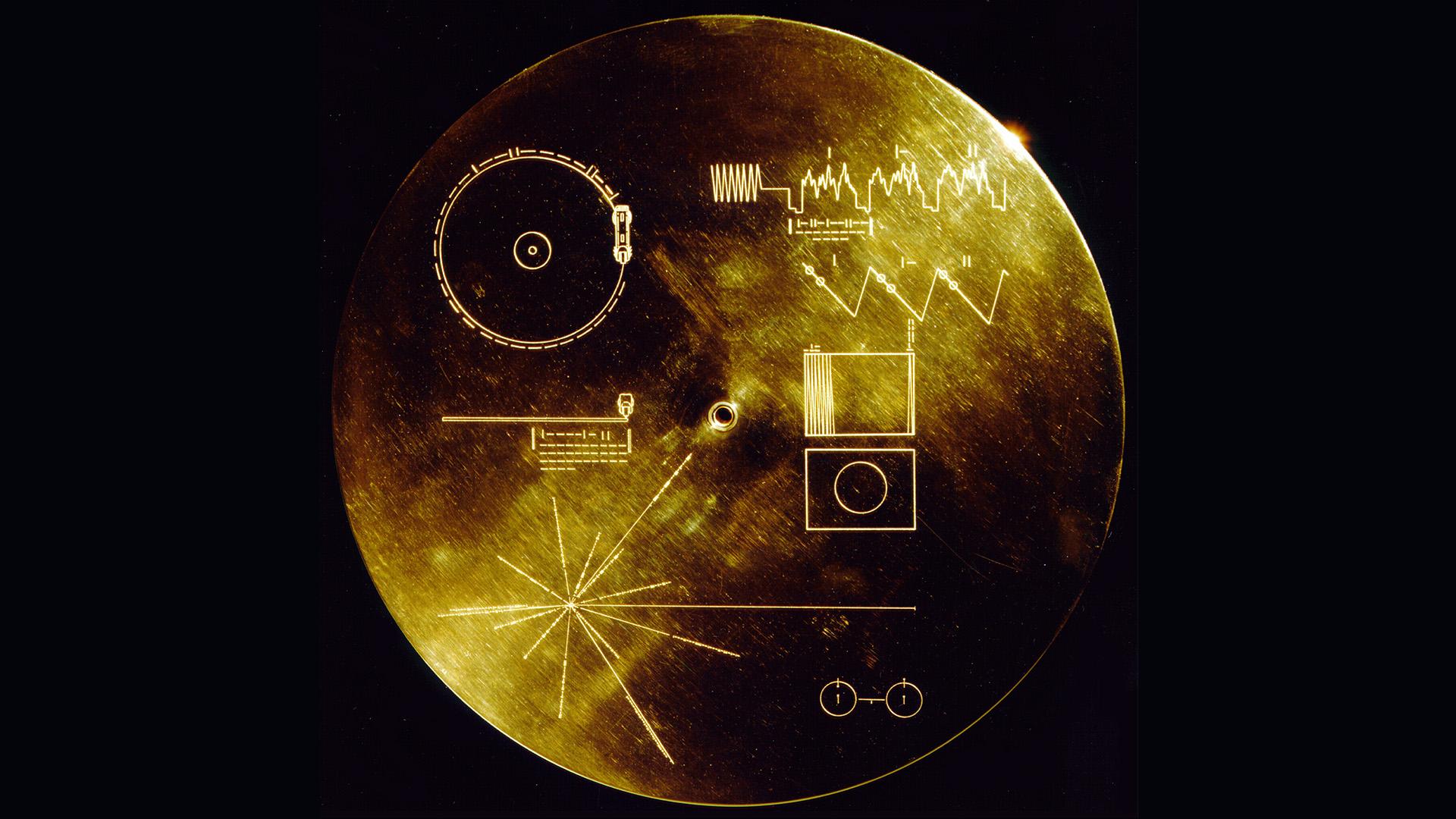

“I’m always mining life for a good story, but all I ever see, I fear, is just my own reflection,” Amy laments, in Flying Couch. Yet the fact is that each of our reflections, each of our sometimes claustrophobic-feeling experiences is rich with comedic and narrative fodder. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Amy’s upcoming book, Artificial, is another family memoir, this time about her inventor-scientist father’s quest to resurrect his father through artificial intelligence (fittingly, Amy has also published single-panel cartoons about enlightened self-driving cars and a robot cat passing the Turing test). We know that “happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way” (per Constance Garnett’s translation of Tolstoy). Purely happy families are also uniformly not funny (hence the TV laugh-track). The hilarity in being a part of a family that bickers, that is unique in its pain and its perseverance, is what allows for what Amy describes as “the moment of relief in the drawing of lines.” What she doesn’t name is the parallel moment of relief and pure delight we feel in the consumption of those drawings, for which I, and my mother, are exceedingly grateful.