Empathic Wit

A renewed need for the genius of Heinrich Heine

By Azade Seyhan

At the end of his 1956 essay “Die Wunde Heine” (The Wound That Is Heine), Theodor Adorno darkly reflected that Heinrich Heine’s perennial theme of hopeless love was an allegory of homelessness. Adorno, forced into exile after the Nazis came to power, thought that Heine’s fate had been literally realized in his mid-twentieth-century present: “It has become the homelessness of all,” Adorno wrote. “All are damaged in nature and language like the banished person that [Heine] was.” There will never again be a Heimat, he asserts, except in a world from which no one will be cast out, a world of truly liberated humanity. He concludes, “The wound that is Heine will only heal in a society that could realize this reconciliation.”

My early encounter with Heine’s empathic yet rebellious voice came in a class taught at Robert College, in Istanbul, by a German professor who had himself been exiled from the Third Reich, Traugott Fuchs. Though he was not Jewish, Fuchs had been expelled from his job in Germany because he tried to organize a protest against the dismissal of his Jewish professors at the University of Marburg. In Istanbul, he joined figures such as literary theorist Erich Auerbach and linguist and literary critic Leo Spitzer in their exodus out of Germany to Istanbul, where he spent the rest of his life. It was here, in the late 1960s, during a period of political instability in Turkey, as members of any group associated with leftist ideology were being persecuted, that Professor Fuchs’s German class organized a contest to produce the best translation of Heine’s 1844 political poem Die schlesischen Weber (The Silesian Weavers) into English and Turkish.

Fuchs was only a junior lecturer in Germany, where he could have stayed to pursue an academic career. Instead, he chose to throw in his lot with his hunted and haunted compatriots in Turkey. He initiated Germanic studies at the University of Istanbul, and while colleagues whose fates he chose to join departed for better career opportunities in Germany and the United States, Fuchs remained on the shores of the Bosporus, which became his proxy Heimat. From there, he kept up a voluminous correspondence with former exiles: Auerbach and Spitzer, Hermann Hesse, Erwin Panofsky, and others. Their exchanges forged a network of communications that reflect a transnational, translational intellectual history of World War II and the postwar period.

Though Fuchs died in relative poverty—he was financially unprepared for retirement and, unlike other exiles, could not collect a pension from the German government—he did not die in obscurity. The Traugott Fuchs Archive Project at Boğaziçi University (formerly Robert College) is the custodian of Fuchs’s correspondence with Auerbach and of Auerbach’s extensive correspondence with Martin Buber and Walter Benjamin, among others. This constellation of relationships, along with Fuchs’s deliberate exodus to Istanbul and his knowledge of Heine are for me touchstones in the greater narrative of the iterative exodus of German culture across time and geography.

Throughout this intellectual trajectory, Heine remains a presence, all the way up to today, as the worst refugee crisis since the end of WWII unfolds in our midst. Millions of people are flocking to Turkey and Germany from the war-ravaged fields of Iraq and Syria. They will never have a home to return to. Heine’s wound has not healed.

More broadly, as the persecution of academics and intellectuals in Turkey, Iran, Russia, China, and certain Arabic countries mounts, the histories and stories of censored, hunted, and displaced writers have come out of the shadows of cultural amnesia. Long after the publication of his landmark work, Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature (1946), Auerbach is not only credited with founding the discipline of comparative literature, at the University of Istanbul, he also has become the subject of an entire field of what may be called Auerbach Studies. Decades after Walter Benjamin’s tragic death, in 1940, his work has achieved a critical appreciation to a degree inconceivable in his lifetime, so much so that he is ranked alongside major twentieth century thinkers such as Freud, Heidegger, and Foucault. His place in the course syllabi of German and other humanities courses at American universities eclipses by far those of Brecht and Heine, if the latter is taught at all.

How does Benjamin’s status as an unemployed Jewish intellectual, an exile in Paris, a theorist of the city, and an art and media critic relate to the intellectual and literary lineage of Heinrich Heine? It is understandable that modern academics, who have been addressing questions of aesthetics through the lens of various media and supra-aesthetic concerns, would consider Benjamin a cherished find in the archaeology of literary and cultural theory. As a genuinely interdisciplinary thinker, Benjamin is referenced by literary theorists, art historians, cultural and intellectual historians, media specialists, anthropologists, and philosophers. But there are many similarities between the two, and in many ways Benjamin is Heine’s intellectual heir.

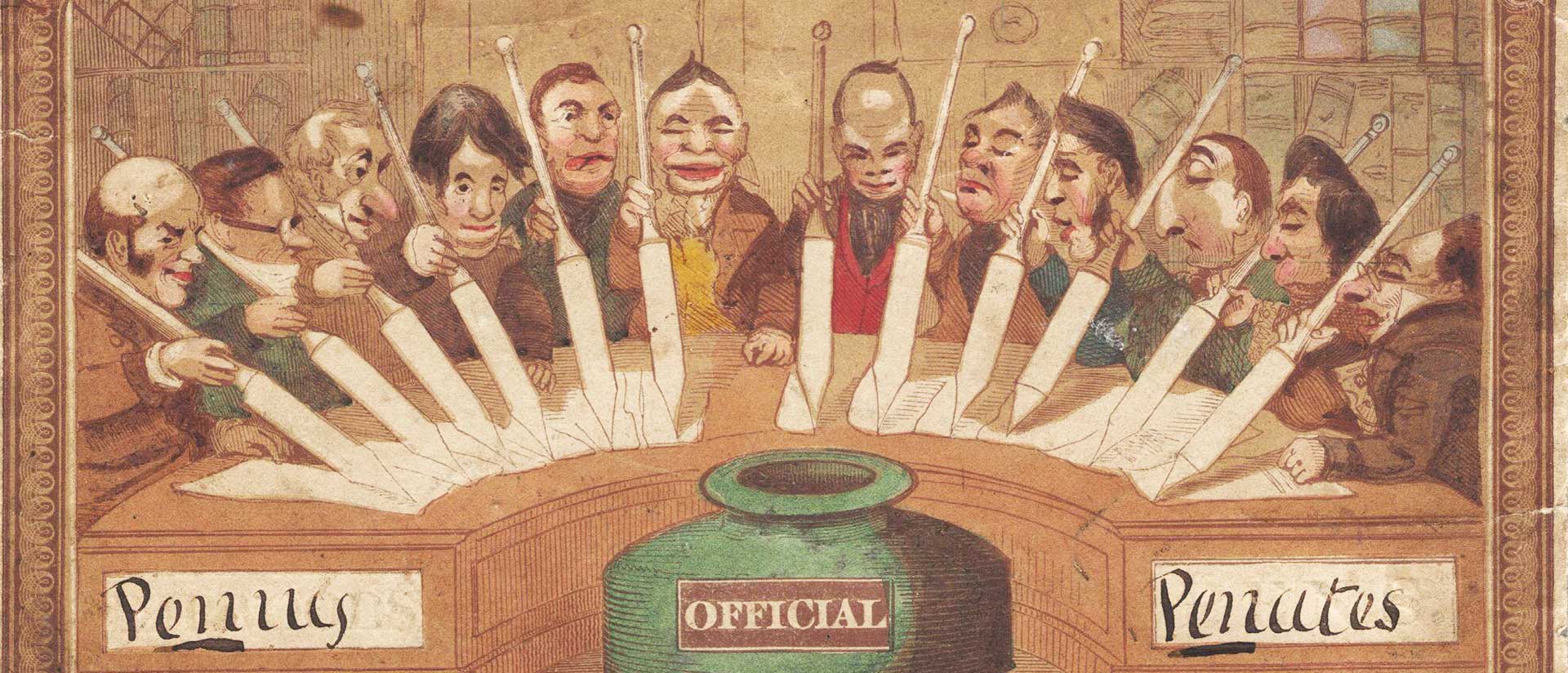

Heine was a formidable critic of German culture, and his critical writings form a genre of cultural negotiation between the end of the Kunstperiode and the age of industrialization. His work as a cultural critic and translator, “foreign correspondent,” travel essayist, philosopher, art critic, political poet, and genre bender constituted not only an early forerunner of the work of the three visionaries of modernity—Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud—but also influenced the foundational tenets of the Frankfurt School, particularly the writings of Adorno and Jürgen Habermas.

Heine was a formidable critic of German culture, and his critical writings form a genre of cultural negotiation between the end of the Kunstperiode and the age of industrialization.

Just as Heine was a chronicler and critic of the passage from the Enlightenment to modern culture, Benjamin was a chronicler of the transition from nineteenth-century industrialization to the age of high capitalism and mass production. Poised at both ends of the European—and, more specifically, German—discourse on modernity, the works of Heine and Benjamin are informed by a keen awareness of the cultural and social consequences of the representational nature of knowledge. Like Heine, Benjamin transgressed boundaries of genres to read works of culture in their sociohistorical contexts. Heine’s critical prose has often been dismissed as unsystematic, lacking in disciplinary solidity, and frivolous because of its relentless irony. Just as the suspicion toward Heine’s liberal views and republicanism was an outcome of his resistance to committing to any political affiliation, so was the reticence toward his revolutionary brand of cultural criticism a result of his refusal to subscribe to a particular genre.

Similarly, because Benjamin was not associated with any particular school of thought—though he has variously been dubbed a Marxist, an anthropological materialist, a messianic critic, and an urban chronicler—his work, until its belated and unexpected efflorescence in the late 1960s, was rarely known and almost never read within any disciplinary field, not even in German. Although Heine, who had an indisputable reputation as a poet in his lifetime, has never been compared to the great visionaries of modernity, his prose writings arguably provide a prototype of Benjamin’s fragmented, cross-genre work.

When Heine is seen in this light, as an intellectual precursor to German critiques of contemporary culture, one questions why this major literary architect of modernity, a world-renowned poet, a witty philosopher of such enormous gifts and knowledge is rarely studied outside German academic circles. When will his work, which resounds so strongly with the concerns of today’s worlds of displacement and disruption, again reclaim its place on the world literary-cultural map? Why has contemporary German criticism been so slow or reluctant to revisit and reassess Heine’s astonishingly prescient representations of censorship, persecution, and forced exile? This is especially curious considering Germany has in recent years become host to an unprecedented number of refugees and thousands of persecuted intellectuals—not least from Turkish universities decimated by President Erdoğan. (Incidentally, a new Turkish translation of Heine’s 1836 Die romantische Schule [Romantizm Okulu], issued by Turkey’s largest publisher, sold out in no time. Heine’s critical reassessment of German Romanticism illuminates the trials and traumas of modernity in a strikingly novel fashion that resonates with Turkish intellectuals and even with the concerns of postmodern thinkers.)

Why has contemporary German criticism been so slow or reluctant to revisit and reassess Heine’s astonishingly prescient representations of censorship, persecution, and forced exile?

Perhaps the absence of a reassessment of Heine as a commentator upon modern exile and its vicissitudes can be attributed to the poet’s ideologically laden reception in his own country. While Heine’s posthumous fame remained cherished in France, England, and many other European countries, he was defamed both by the Nazis and, quite oppositely, by Karl Kraus, the Austrian-Jewish satirist, essayist, and poet who was thrice nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. Although these acts of denigration came from opposing ideologies, they did not cancel each other out. Each instead caused long-term damage to Heine’s critical reception. As Habermas noted in 1986, Heine was doubly banned from participating in political formation: firstly through exile, and secondly through censorship.

It’s high time to reconsider Heine’s critical legacy. Now more than ever, the work of this brave and hunted poet of modernity has much to teach us, especially to those who, like him, have been robbed of their home and history. No writer of his stature has empathized more with the plight of people persecuted and exiled by their own people or governments. Nowhere is this empathy more strikingly revealed than in Canto XV of his epic Atta Troll (1843), in which he tells of a moving encounter with a family of Cagots, a persecuted minority group in western France and northern Spain. Despite their Christian faith, the Cagots were treated like pariahs, forbidden to touch food at public markets or even to enter churches, except unseen, through a back door. Heine enters the hut of the Cagot family, addresses the father as his “brother” and kisses his child. Heine calls their cruel exclusion from the community “a dark heritage from the dark age of faith.” His affection for the outsider is displayed without false sentiment, a characteristic of his empathic identification with people excluded from the social order.

Today, exile has become a permanent condition for millions of persecuted and displaced people strewn throughout the Middle East and Europe. Populist movements bordering on fascism, gross inequalities in a rapidly globalizing world, attacks on refugees, ethnic persecution, fomented by powerful political heads from the Americas to the Far East, have created, in the words of the late Algerian novelist Assia Djebar, “a random and bloody lottery” we experience on a daily basis. “Such a chain of violence and its blind acceleration certainly emphasize the uselessness of words,” she wrote, “but their necessity as well.” Heine’s words—in prose poems, critical essays, poem cycles, travelogues, journalism, autobiography, and philosophical fragments—bear testimony to this hard truth, and to literature’s unique potential to speak through the ages.

Azade Seyhan, the fall 2019 John P. Birkelund Fellow in the Humanities, is a professor of humanities and German at Bryn Mawr College.