Undercover Oughts

Social surveillance and moral reform

by Jacqueline Ross

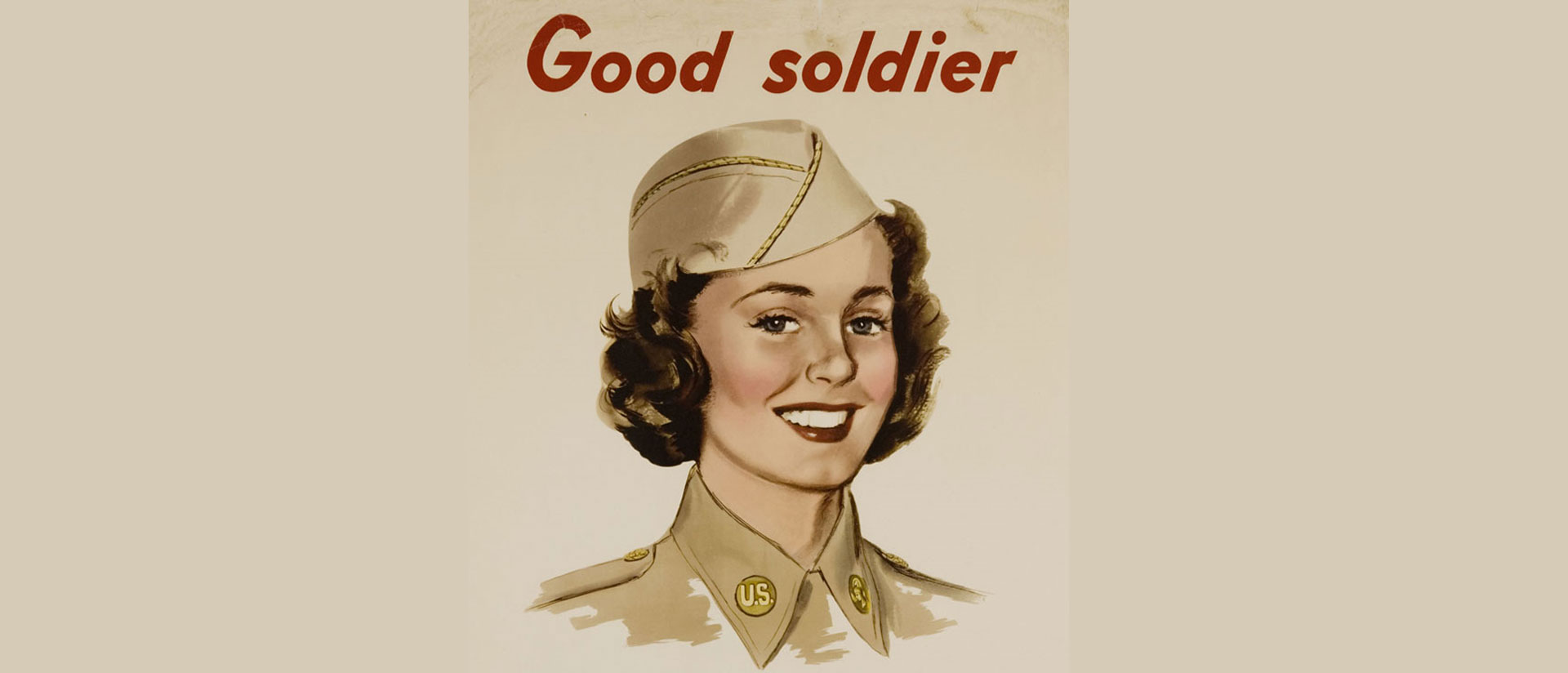

As caricatured in dozens of films of and about the early American century, crackdowns on late nineteenth and early twentieth-century saloons, dancing halls, brothels, and gambling parlors were often pursued by religious activists and undercover entrepreneurs. Fired with the zeal of social improvement, these enthusiastic agents were hired by Progressive reformers—and often against the wishes of the police.

But the agenda of these undercover moral reformers was not limited to cracking down on vice. Their bigger aim was to change the social conditions that underlay these vices—and, not least, to keep an eye on the leisure habits of recent immigrants. In New York, prominent social reformers like Lillian Wald and Jacob Riis, supported by organizations such as the Tenement House Committee and the Committee of Fifteen, solicited recommendations from organizations such as the Central Federation of Churches and Christian Workers, and the Church Association for the Advancement of the Interests of Labor. They did so for “insider investigators” who were familiar with the neighborhoods and languages of recent immigrants and could serve as undercover investigators of prostitution in tenement housing.

Undercover investigators operated in teams of two, paying tenement house prostitutes for their services and then filling out pre-formatted reports that were signed by a notary public and could serve as sworn testimony admissible in a court of law, with the aim of suggesting reforms to housing conditions that would decrease the incidence of prostitution. Undercover agents would pay prostitutes in the presence of an investigating partner; the reports were used not only against the women but also against the owners of tenement houses who allowed their buildings to be used by prostitutes. Not incidentally, these investigations exposed the graft, complicity, and corruption of the local police department, which tolerated the presence of “disorderly houses” in immigrant neighborhoods.

Similar undercover operations targeted saloons and gambling halls in immigrant neighborhoods, as well as dance halls where white and black New Yorkers mingled. In her fascinating study New York Undercover (2009), sociologist Jennifer Fronc has documented the extent to which these operations—undertaken by social reform organizations like the Committee of Fourteen and anti-saloon activists such as the Anthony Comstock Society for the Suppression of Vice—represented efforts by “nativist” reformers committed to racial segregation and suspicious of recent immigrants to police the sexual and leisure habits of immigrants and racial minorities.

Many of these reform societies used volunteers from immigrant communities to serve as undercover agents, and they hired private detectives to gather evidence about saloons that were selling liquor outside of approved hours, all with the aim of shutting down these establishments.

But moral entrepreneurs like Anthony Comstock also used undercover tactics to investigate the Art Students’ League, in New York, for selling catalogues that featured artistic representations of nudes. The Committee of Fourteen would engineer interracial encounters in saloons and dance halls known to welcome black and white customers. Documentation of liquor being served to women under the age of 18 served as a pretext for shutting them down, even though New York State had passed strong anti-discrimination laws in 1895, 1905, and 1909. Fronc describes the Committee of Fourteen’s undercover tactics as an effort “to protect [. . .] the morality of white women, [who] were portrayed as ‘victims’—of alcohol or seduction, or of their own bad judgment,” gathering evidence of “intoxicated white women in black-owned establishments as justifications for sanctioning black proprietors.”

Social reformers were able to use undercover tactics successfully because they were allowed to conduct their own raids, make their own arrests, and use their sworn affidavits and reports as evidence, pursuing primarily a strategy of attacking the liquor licenses of the establishments they targeted, alongside criminal sanctions against individual purveyors of vice. This not only kept a state monopoly of undercover tactics from taking root; it also meant that moral entrepreneurs could circumvent an unwilling police force. These private actors actually often ignored the police entirely, though they sometimes either served or competed with its local representatives, and sometimes deployed undercover tactics against them, by exposing police corruption in cities dominated by powerful political bosses.

Social reformers were able to use undercover tactics successfully because they were allowed to conduct their own raids, make their own arrests, and use their sworn affidavits and reports as evidence, pursuing primarily a strategy of attacking the liquor licenses of the establishments they targeted, alongside criminal sanctions against individual purveyors of vice.

In New York City during the Progressive era, for example, prosecutors who wanted to fight prostitution hired Pinkerton undercover agents, in the face of a recalcitrant and complicit police department that tolerated brothels in exchange for bribes. Periodic scandals and reform commissions brought the likes of Theodore Roosevelt to power as a New York police commissioner in 1892. Roosevelt took it as his mandate to eliminate brothels and to strictly enforce liquor regulations, including, most controversially, those that prohibited the sale of liquor on Sundays. In the face of resistance from the police rank and file, Roosevelt allied himself with social reformers such as the Reverend Parkhurst, who himself had gone undercover to document many brothels that New York police had claimed to know nothing about. Roosevelt was celebrated in the press for going undercover himself on midnight rambles with Jacob Riis and others to investigate and surprise police officers who frequented saloons and brothels while on duty.

Seen from a sociological point of view, American undercover tactics of the early twentieth century were a form of social control that supplanted or supplemented the exercise of police power in many spaces that were under-policed, and where law enforcement’s presence was often ineffective, corrupt, or both. Sometimes the private and public sector worked together, sometimes in parallel, sometimes one used the other, and sometimes there was conflict between them. Still, these two forces were always in dialogue.

These feature s of American policing had roots in the undercover tactics of other cultural milieus of the time, namely those of cultural elites who deployed undercover tactics for a variety of purposes, most unrelated to the search for evidence or criminal prosecution. American sociology and journalism of the late nineteenth century was practiced by the “down and outers,” most famously Stephen Crane, Hutchins Hapgood, Jack London, and Nelly Bly, who dressed up as prostitutes, waitresses, and factory operators in order to secretly investigate and then write about what was happening among the burgeoning underclass. Undercover journalists posed as sweatshop workers, harried waitresses, and insane-asylum inmates, writing about their experiences in these and other roles with which the public could empathize. Social scientists, writers, and reformers frequently went undercover across class lines and variously configured racial divides—from the late nineteenth century through the 1950s—to develop vivid accounts of the lives and struggles of workers, tramps, the unemployed, and of ethnic, religious, and racial minorities.

Social scientists, writers, and reformers frequently went undercover across class lines and variously configured racial divides—from the late nineteenth century through the 1950s—to develop vivid accounts of the lives and struggles of workers, tramps, the unemployed, and of ethnic, religious, and racial minorities.

Such accounts were themselves strategies for breaking down social barriers, as female sociologists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries used undercover tactics to gain entry to male-dominated fields—including academia itself. Jennifer Fronc writes that this undercover technique “allowed them to do the work for which they were trained in graduate school. [These women] succeeded in authoring and publishing important articles that appeared in leading professional journals, and they preceded the Chicago School of Sociology by a decade.” Examples include the work of Annie MacLean, who published “Two Weeks in Department Stores” in the American Journal of Sociology in 1899, after a stint as a shop-girl in a Chicago department store.

Undercover tactics like hers eventually became mainstream in academia but were later rejected as “unscientific.” In the 1950s, the Chicago School of sociology became known for pioneering new immersion methods of urban ethnography and interpretive sociology through the work of Everett Hughes, Lloyd Warner, and Herbert Blumer, who championed the now-classic methods of urban ethnography and interpretive sociology. Beginning in the 1950s, American sociologists started going undercover to observe gay sexual mores in public bathrooms; the practice of speaking in tongues in Pentecostal churches; and various millennial cults. Once conceived of as a form of participant observation known as “complete participation,” the undercover method’s fall from grace began in the late 1950s, even though deep immersion methods—without the use of deception or disguise—have been used more recently by sociologists such as Sudhir Venkatesh (2008), who has written about what it is like to be a gang leader, and Alice Goffman (2014), who has written about what it is like to be on the run from the police in the high-crime inner-city neighborhoods of Philadelphia.

In the United States, deep immersion and participant observation continue to be used widely both in journalistic and ethnographic investigations of inner-city life, from undercover discrimination testers to undercover “field experiments” that social psychologists use to study, for example, the prevalence of cheating, as in the work of Dan Ariely. There are also American restaurant critics who don elaborate disguises to simulate the experience of ordinary restaurant customers, or, in the case of former New York Times restaurant critic Frank Bruni, go undercover as waiters in order to tell the public about what it is like to work in a restaurant. The list goes on: secret shoppers, TV shows like Undercover Boss, and private anti-crime initiatives—such as the TV show To Catch a Predator—use undercover tactics either to mimic the experience of ordinary members of the public; to reveal to the powerful what the workplace looks like to their employees; or to respond in an entrepreneurial manner to moral panics about sex offenders who prey on gullible children on the internet. Across the pond, the German journalist Guenther Wallraff became famous for using undercover tactics to expose the working conditions of Turkish migrant workers, and for taking a job with Bild to expose its muckraking tactics.

Far from being the preserve of the state, American undercover tactics are an established technique for obtaining and revealing an “insider’s view” of a variety of social milieus. They can be used by cultural elites to make the experiences of the underprivileged, the unsophisticated, or the ordinary accessible to others, and to invite identification and empathy across ethnic, geographic, cultural, and class lines in a heterogeneous society. The moral history of this kind of fondness for surveillance in America simultaneously highlights that Europeans view undercover tactics as a form of state surveillance—as a form of trickery practiced by the powerful against the weak. This is particularly poignant as issues of digital privacy remain at the fore of European minds, especially in Germany. Americans, more lax in their view of digital privacy, view undercover tactics not just as mineable sources of television entertainment, but also as an epistemological strategy to be deployed across all sectors of society, as the state struggles to keep pace with private variants of similar methodologies. □

This essay is derived from a chapter entitled “Undercover Populism,” in the edited volume Contemporary Organized Crime, published by Springer in summer 2017.

Photo: Prohibition group (detail), September, 1922. Print from glass negative. National Photo Company Collection, Library of Congress. Call Number LC-F81-20369