The Subject Shouldn’t Change

A brief conversation about whiteness

With Claudia Rankine

The interview below was conducted with Yale University professor, poet, and writer Claudia Rankine, a Distinguished Visitor at the American Academy in November 2019, as part of the Academy’s Beyond the Lecture podcast series. Rankine was completing her latest book, Just Us: An American Conversation (Graywolf, September 2020), about the dynamics and difficulties of talking about race in America, and how those conversations might progress beyond their sticking points. The following interview, conducted by producer Tony Andrews and abridged here for space, can be heard in its entirety at americanacademy.de or on the Beyond the Lecture podcast on iTunes, Spotify, and SoundCloud.

Claudia Rankine: Just Us is a book that seeks to investigate how conversations derail themselves. What kinds of emotions we have that cause us to stop or will us forward in uncomfortable conversations around race. Each section of the book is a recounting of a conversation with someone. These conversations were then brought to a therapist, a factchecker, and a lawyer, before my memory rendition of the conversation was returned to the person I had the conversation with, with an invitation for them to respond.

Beyond the Lecture: In the conversations you had for the book, a lot of white men identify with a feeling of exacerbation at the moral indictment that is implied in the term “white privilege.” Could you comment on that?

CR: I think it’s one thing to feel like the subject has been addressed enough already. But if the reality of black people is not changing, then the subject shouldn’t change. People are acting as if the times have changed and black people are talking about something in the past rather than addressing something that is happening right now. And if the same things keep happening, then the same things will be said. What they might think about is why the same things are being said. So, clearly the reality hasn’t changed drastically enough if you can read the paper, turn on the television, and see that black kids are being killed. Unarmed black children are being killed by the police, and the police are getting off; that is a profound problem. It’s not a little problem, it’s a profound problem. That’s the thing they should have a moral problem with, not that they’re being asked to account for their kind of passive collaboration with this force of injustice.

I think it’s one thing to feel like the subject has been addressed enough already. But if the reality of black people is not changing, then the subject shouldn’t change.

BTL: There’s often a focus here on the question of time, like: “How long are we supposed to feel bad about this?”

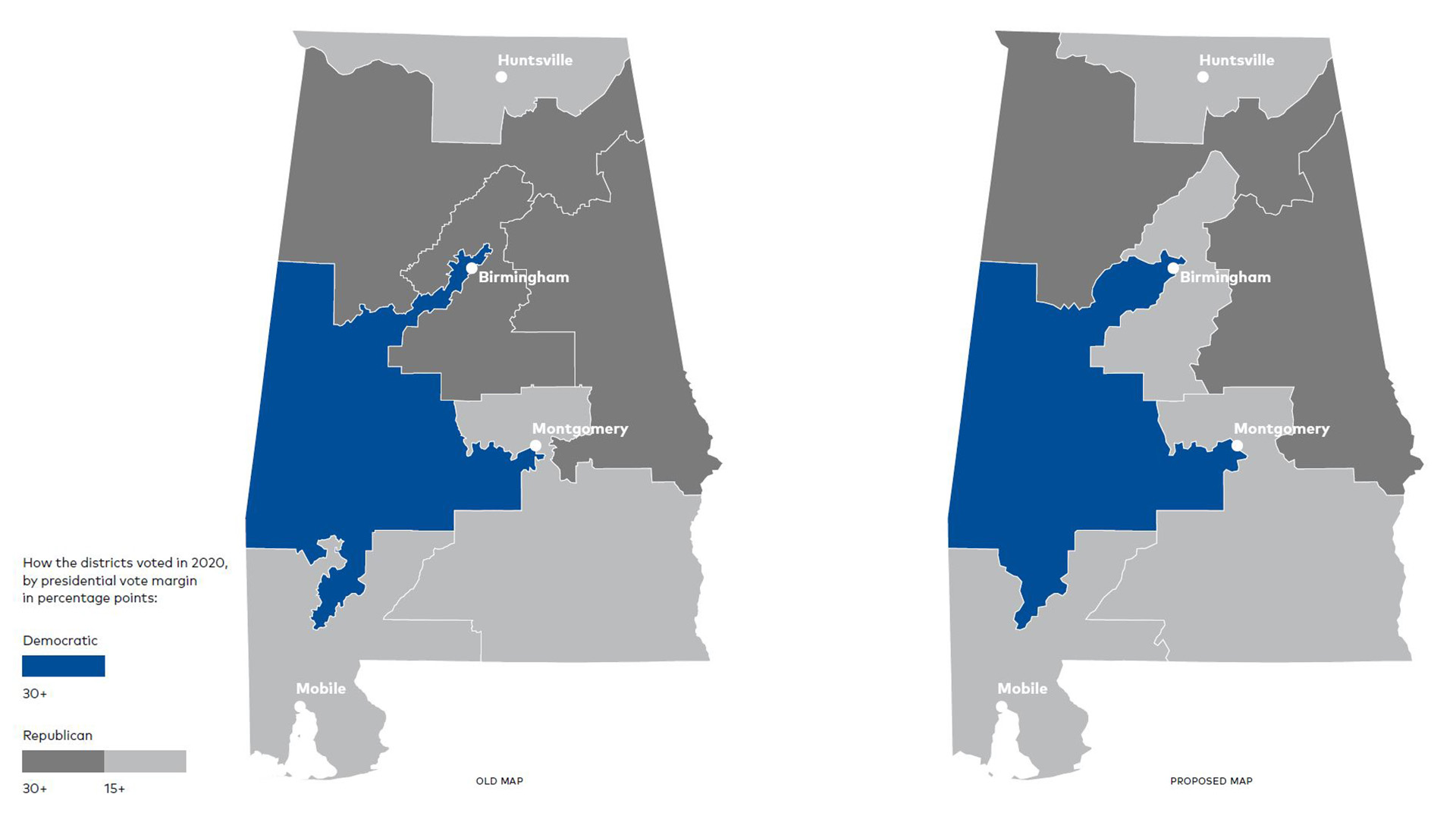

CR: The problem with that is the idea that they’re being asked to be accountable to slavery, when that’s not what anybody is talking about. We’re talking about a system of mass incarceration. Do you know how many black people are in prison? We’re talking about the defunding of schools in certain neighborhoods. We’re talking about the inability to buy homes. We’re talking about vast discrepancy of wealth in the United States between people of color and white people. This is not about slavery, even though where we are today is the afterlife of slavery; it’s the same policies reinstated under a different name.

BTL: For people to feel psychologically good about themselves, they need to feel like they’re good people. The discussion of white privilege seems to take that option away, and if you feel like you’re fundamentally bad or not doing enough or have no access to feeling you’re a good person, maybe that’s the kind of damnation that is being expressed here.

CR: Well, white people have to get over the idea that likeability is part of it. I am not talking about any individual specifically and their particular likeability. I am sure there are good people, nice people, generous people. We’re talking about what it means to live in a system where certain people are outside systems of justice. Until we change the system, we are failing. And that “we” is collective. That’s including me. [. . .] I think societies have criminalized blackness to the point where white people feel afraid of black people. It’s not even something that white people understand is constructed in their imagination. It is reinforced in films, in advertisements. So the fear is a real emotion. The question is, Is it actually attached to me? That’s what I would ask them to ask themselves. Is the person standing in front of you acting in any way to actually solicit that fear? There is this great thing in the train station in Boston where they said, “If you see something, say something,” but then they added, “Remember, seeing something means seeing an action, not a person.” I love that because it reminded me that they were thinking that we don’t want people to racially profile people. But that is where the fear is. It’s inside the imaginative possibilities of whiteness and not in actions of people. What one really needs to investigate is, as legitimate as that emotion feels, what is soliciting it.

We’re talking about what it means to live in a system where certain people are outside systems of justice. Until we change the system, we are failing. And that “we” is collective.

BTL: That’s on one level, on the level of white person’s emotions. But on the black side there’s self-censorship, where I need to be emotionally inert so as to not rile anyone.

CR: One of the ways that people of color and women have been silenced by white people is that they’ve been classified as, if they’re women, hysterical, unable to be rational, and if they’re black, they’re angry. And what that does is limit your possibility of reactions to certain responses coming from white people. Because the minute you say no, you’re irrational. The minute you say no, you’re angry. Rather than maybe this moment, the legitimate and rational response to it is anger. But that has been taken off the table for anyone who is not white.

BTL: At your lecture at the American Academy, you mentioned the concept of a white space and how, as a black person, you can enter that space but it will always be marked.

CR: Exactly. People say, “What are you talking about? Anybody can come in here!” But if you go in there, everyone looks at you, and it’s not always hostile. Sometimes they look at you in a welcoming way. But the idea is that your entrance has been noted. It’s being noted because there was a time when you weren’t allowed into the space. Everyone is recognizing the fact that it’s a new thing that you’re entering. It’s disingenuous not to pay attention to the noting of that. Because the spaces in and of themselves are just spaces and why people believe that they are white spaces is because they only let white people in them for the longest time. [. . .] We’re interacting with people every day; we’re making decisions about how people get treated every minute of every day. And clearly that treatment has been wanting. It’s happening in restaurants, in banks, in hospitals. This double standard in terms of how one person is treated versus another. So we have to be accountable to the fact of the matter, and the system is as the system is. I just think this magical thinking that we can just kind of wish it away and be good people without being accountable to the realities and to the systemic failures that happen is never going to get us anywhere.

People say, “What are you talking about? Anybody can come in here!” But if you go in there, everyone looks at you, and it’s not always hostile. Sometimes they look at you in a welcoming way. But the idea is that your entrance has been noted.

BTL: The discourse around white privilege is similar to how people feel after a climate-change documentary, in that they feel the enormity of the issue but also a certain sense of personal lack of agency or ability to change things. Is there a distilled directive you would give them? “Okay, now go and empower,” or “Now go and break down injustice”? Or would you say that this issue just can’t be boiled down into six steps that we could do to change the planet by 2025?

CR: Well, you know you could now go and vote in ways that allow others to live, understanding that your life already has a pathway. You could also now go and understand that no one is faulting your goodness but only asking you to look at the realities as they reflect on the lives of people who perhaps are not white. It’s a question of perspective. It’s a question of what are you voting for, how you are continuing to limit the civil rights for other peoples. These are tangible things that can happen in a life. □