Sui Generis

Aggression, Atrocity, and the Verbrecherstaat

by Lawrence Douglas

In its March 8, 1965 edition, the German newsweekly Der Spiegel devoted a full 16 pages to an interview that the magazine’s publisher, Rudolf Augstein, had conducted with the philosopher Karl Jaspers. The topic—whether the Federal Republic’s statute of limitations for the crime of murder should be lengthened—hardly seemed to warrant such a dedication of space or to promise a profound discussion between Germany’s most prominent publisher and arguably its most renowned living philosopher.

And yet, the German statute of limitations had emerged as a topic of passionate and acrimonious domestic and international debate. By the terms of the Federal Republic’s criminal code, the prosecution of every crime was controlled by a statute of limitations. Cases of assault and battery had to be prosecuted within five years of their commission. Manslaughter had a fifteen-year prescriptive period. Murder had the longest statute of limitations, but even that was only twenty years.

This meant that in 1965 the twenty-year statute of limitations on murder prosecutions was about to toll on Nazi-era crimes. Without a statutory extension by the Bundestag, the looming date of May 8, 1965—the twentieth anniversary of the end of the war in Europe—would have signaled the end of all Nazi-era prosecutions in the German Federal Republic. Thereafter, West German prosecutors would be powerless to bring criminal charges against those who planned, perpetrated, and facilitated Nazi mass atrocities. May 1965 would have marked the beginning of an era of impunity.

So matters stood when publisher Augstein traveled to the Swiss city of Basel to interview the famous philosopher, then in this eighty-third year. Before the war, Jaspers had taught at Heidelberg, Germany’s oldest and most venerable university, where, among other notable accomplishments, he had served as Hannah Arendt’s Doktorvater. Jasper’s wife was Jewish, and so he was forced to resign his professorship during the Third Reich, before seeing his work banned altogether. Less than sanguine about Germany’s democratic prospects after the war, Jaspers took a professorship in Basel in 1948, where he remained a vocal critic of Germany’s failure to reckon with its Nazi past.

At the outset of the interview, Augstein made clear that he wasn’t interested in the technical juristic question of whether extending the statute of limitations could be squared with the German Basic Law, or Grundgesetz—Germany’s postwar constitution. Instead, he called upon Jaspers to weigh the matter from a “moral standpoint,” asking him to “bear the following in mind”:

“During the conquest of Jaffa, Napoleon took 3000 prisoners. [. . .] To save on powder and bullets, he had them all bayonetted to death. Many of these captives were in company of their families, and these families—the women and children—were also slaughtered by bayonet. Nevertheless, no one suggested that anyone beside Napoleon should be held responsible for this massacre. By contrast, today [. . . in the case of] Nazi crimes, we act as if it’s typical and proper to put on trial anyone who may have shot women and children under orders.”

Jaspers pushed back against Augstein’s analogy:

“Don’t we need to recognize an essential distinction? History knows many such stories as the one about Napoleon. In this case, the representative of the state, Napoleon, committed a crime. But the state in its essence and entirety was not criminal. The decisive point is to recognize that the Nazi state was a Verbrecherstaat, a criminal state, not a state that happened to commit crimes.”

Hitler was hardly the first tyrant to rule a European state. But the Nazi state, Jaspers insisted, was not a simple tyranny. In the case of Nazi Germany, the problem was not with the excesses of a particular statesman or branch of government. The state in its essence was a criminal organization. The Nazi state was a Verbrecherstaat, a criminal state, not a state that happened to commit crimes.

“Criminal” is a legal, not a moral, category. From a classic positivist perspective, the term Verbrecherstaat sounds almost oxymoronic. The law typically views criminal acts microscopically—that is, it construes crimes as small-scale, deviant acts harmful to community order. Criminal acts are understood to be most commonly committed by individuals against other individuals or against property; the very concept of criminal responsibility typically attaches to individuals and not organizations.

But this only begins to touch on the term’s dissonance. Beginning with Thomas Hobbes, in the mid-seventeenth century, Western political and legal thought had been committed to the proposition that the state represented the greatest bulwark against the disordering effects of violence in civil society and that obedience to the law represented the paradigmatic virtue of the pacified citizenry.

As the guarantor of security, order, and lawfulness, the state, in the classic model, enjoyed two basic prerogatives of sovereignty: in internal affairs, the state claimed a monopoly on legitimate force—with “legitimate” understood in largely a descriptive rather than normative sense. What made the state’s monopoly legitimate was the inescapable fact that the state was endowed with the power to name, prosecute, and punish crimes—viz., the state’s monopoly was legitimate because it had the de facto power to declare it as such. In external affairs, the state enjoyed the power to name its enemies and to wage war against them. The theory of sovereignty understood all states as being formally equal. This formal equality permitted states to violently clash with one another but denied them the right to scan the legality of how rival sovereigns exercised their internal police powers or their decision to use military force in defense of their interests.

As Jaspers realized, Nazi crimes exploded this model. The concept of the Verbrecherstaat illuminated how Nazism had deformed the state into the principal perpetrator of crimes, the very agent of criminality. The advent of the Verbrecherstaat mandated, however, more than simply a conceptual or philosophical rethinking of the meaning of statehood. It required a fundamental revision of juridical understandings, a radical break from the classic juristic treatment of sovereignty. In the peroration of his opening address at Nuremberg, the chief American prosecutor Robert Jackson framed the problem thusly: “Civilization asks whether law is so laggard as to be utterly helpless to deal with crimes of this magnitude by criminals of this order of importance.” Required was a vast and ambitious project of juridification that would subject the mass violence of states and state actors to the sober ministrations of the law.

The concept of the Verbrecherstaat illuminated how Nazism had deformed the state into the principal perpetrator of crimes, the very agent of criminality.

The Nuremberg trial, presently celebrating its seventy-fifth anniversary, marked a crucial step in this project. Nuremberg insisted that law could deal with the challenges posed by macro-criminality, but that the effort would require extraordinary legal innovations. Mastering the macro-crimes of the Verbrecherstaat would require, first and foremost, novel categories of wrongdoing. These new categories had to be sufficiently flexible and capacious to handle atrocities that spanned a continent, enlisted the participation of tens of thousands of perpetrators and accessories, and were supported by a complex organizational and logistical apparatus. Moreover, these new incriminations had to be able to penetrate the shield of sovereign immunity that traditionally shielded state actions from external legal scrutiny.

But submitting state action to legal judgment also required a crucial answer to a basic juridico-historical question: What constituted the paradigmatic crime of the Verbrecherstaat? To put it differently, if, as Jaspers insisted, the Verbrecherstaat was criminal to its core, what crime or constellation of crimes made for the Verbrecherstaat’s core criminality? For Jaspers, the answer was obvious: the paradigmatic crime of the Nazi state was the extermination of European Jewry. In his Spiegel interview with Augstein and in Wohin treibt die Bundesrepublik?, his short, pessimistic book published a year later, in 1966, Jaspers made clear his belief that the Verbrecherstaat was, at its core, an exterminatory state. What set the Hitler state apart from other tyrannical regimes was its planning and implementation of a continent-wide campaign of civilian mass-murder.

This is hardly controversial stuff, and most people today would agree that the Holocaust represented the distillation and quintessence of Nazi criminality. Shift our attention to more recent mass crimes—the killing fields of the Khmer Rouge, ethnic cleansing in the Balkans, the massacre of the Rwandan Tutsis—and we reach a similar conclusion. It is acts of mass atrocity committed against targeted civilian groups that define the core crimes in international law. It is these acts which arouse the greatest international outrage, which create the most exigent pleas for intervention, and which raise the most insistent cries for a juridical reckoning.

At Nuremberg, however, matters were seen quite differently. More than twenty years before Jaspers described the Third Reich as a Verbrecherstaat, the great Soviet jurist Aron Trainin used similar language to describe Hitler’s Germany. Trainin, who was Jewish, published a short book on Nazi criminality in 1944, at a time when the struggle against Hitler’s Germany had just taken a decisive turn, when the Soviets recaptured much of the territory of southern Russia and Ukraine. In Hitlerite Responsibility under Criminal Law, Trainin characterized the Nazi state as criminal in its essence, but, in stark contrast to Jaspers, Trainin did not identify the Nazis’ extermination of his fellows Jews as the regime’s core crime. Rather, he insisted that what made Nazi Germany a Verbrecherstaat was its aggression—its unprovoked attack on its neighbors—most notably, its scorched-earth invasion of the Soviet Union.

Nuremberg represented the triumph of Trainin’s perspective. The Charter of the International Military Tribunal (hereafter IMT) that tried 22 major Nazi war criminals in Nuremberg’s Palace of Justice introduced into international law two novel categories of criminality: “crimes against peace,” the locution pioneered by Trainin, and “crimes against humanity.” The Charter defined the former as the “planning, preparation, initiation or waging of a war of aggression,” the latter as “inhumane acts committed against any civilian population,” including but not limited to murder, extermination, and enslavement. Crimes against peace constituted acts of military aggression; crimes against humanity, acts of state sponsored atrocity.

Of the two, “crimes against peace” constituted the gravamen of the prosecution’s case. Aggression and not atrocity was understood as the paradigmatic crime of the Verbrecherstaat. Crimes against peace appeared first among the crimes over which the IMT had jurisdiction, and it was the only crime to which the conspiracy charge applied. The so-called “nexus” requirement, drafted into the IMT Charter, restricted the tribunal’s jurisdiction over “crimes against humanity” to acts connected to Nazi aggression and war crimes. This limitation meant that the tribunal lacked jurisdiction over the Nazis’ forced sterilizations of the physically and mentally “unfit,” the November pogrom against the Reich’s Jews, and all other German-on-German atrocities perpetrated before the Wehrmacht crossed the Polish frontier on September 1, 1939.

Aggression and not atrocity was understood as the paradigmatic crime of the Verbrecherstaat. Crimes against peace appeared first among the crimes over which the IMT had jurisdiction, and it was the only crime to which the conspiracy charge applied.

At Nuremberg, the prosecution’s focus on the Nazis’ crimes against peace shaped how it understood and presented evidence of the Nazis’ crimes against humanity. For example, while Justice Jackson recognized, in his opening statement, that the Nazis had elevated the killing of Jews to an end unto itself, he also insisted that atrocities perpetrated against Jews were a means—that is, the Nazis used the persecution and killing of Jews to eliminate obstacles to waging war and as a test case in the subjugation of conquered people. In so arguing, Jackson sought to satisfy the required nexus between pre-war crimes against humanity and the Nazis’ war of aggression, thus bringing these early crimes within the Tribunal’s jurisdiction. Alas, the effort failed; the court refused to pass judgment on these pre-war acts, but the deeper point remained: that Jackson’s historical narrative was shaped by the trial’s organization around acts of aggression.

That acts of aggression, and not of atrocity, should have been understood as the paradigmatic crime of the Nazi Verbrecherstaat may seem odd to us today. But it made sense at the time, as the effort to criminalize aggression had emerged as the principal preoccupation of international lawyers in the decades before Nuremberg. The horrors of the First World War—the staggering futility of trench warfare, the sheer wastefulness of men and matériel—gave powerful impetus to treat the launching of war, and not any associated atrocities, as the principal catastrophe. In its report of March 19, 1919, prepared for the Paris Peace Conference, the Entente’s “Commission on the Responsibility of the Authors of War” accused Germany of having started “a war of aggression” before regretfully acknowledging that aggressive war “may not be considered as an act directly contrary to positive law, or one which can be successfully brought before a tribunal.”

In the interwar years, international jurists worked tirelessly, if not entirely fruitfully, toward filling this gap in positive international law by seeking to outlaw the unprovoked resort to warfare. Édouard Descamps, a prominent Belgian lawyer and a member of the League of Nation’s Advisory Committee of Jurists, proposed the creation of an international criminal court with jurisdiction over both conventional war crimes and acts of aggression. Vespasian Pella, the renowned Romanian jurist and a leading member of the Association Internationale de Droit Pénal, provided greater clarity to the effort by offering a detailed definition of the crime of aggression and by insisting that individuals be held responsible for its violation. Although the Geneva Protocol of 1924, which declared aggressive war “a violation of th[e] solidarity [of nations] and . . . an international crime,” failed to gain acceptance in the League of Nations, four years later the international community witnessed the sweeping ratification of the Kellogg-Briand Peace Pact in 1928, a lapidary instrument—the entire treaty consisted of two sentences—that purported to outlaw war altogether.

With seventy-five years of hindsight, we can say the triumph of the IMT’s aggression paradigm proved short-lived. Even at the time of the proceeding, critics attacked the notion of crimes against peace as inadequately defined and as a violation of the principle of nullum crimen sine lege, the basic principle of legality that bars the application of retroactive criminal law. The criticisms were hardly trivial. Notwithstanding the agitations of international lawyers in the decades before Nuremberg, it remained unclear whether international law had actually repudiated the doctrine of sovereignty that treated all wars as equally lawful. The 1919 Commission on Responsibility clearly concluded that German aggression had not constituted a recognized international crime. So when had the alleged change occurred? Did it suddenly happen on August 27, 1928, with the signing of the Kellogg-Briand Pact? True, the Pact spoke of renouncing war, but it never mentioned criminalizing aggression, which, in any case, it left undefined. At best, the IMT could insist that sometime before September 1, 1939, the international community had abandoned the classic doctrine and had criminalized aggression.

Even at the time of the proceeding, critics attacked the notion of crimes against peace as inadequately defined and as a violation of the principle of nullum crimen sine lege, the basic principle of legality that bars the application of retroactive criminal law. The criticisms were hardly trivial.

At Nuremberg, the horrific quality of Nazi aggression served to hide the instabilities within the Charter’s framing of the incrimination. As Trainin had noted, Hitler’s Ostkrieg split the difference between aggression and atrocity. The Ostkrieg was a war of annihilation; atrocity followed in the wake of the Wehrmacht’s advance, with SS Einsatzgruppen combing the conquered countryside and murdering hundreds of thousands of civilians, principally Jews. But atrocity was also the very means of waging war. In the case of the Ostkrieg, aggression referred not simply to warfare that was unprovoked but to warfare waged with such astonishing brutality that the distinction between aggression and atrocity essentially vanished.

But no sooner had the IMT delivered its verdicts than the concept of crimes against peace began to show its instabilities. Nuremberg’s companion tribunal in the Far East likewise convicted several leading Japanese statesmen and generals of waging a war of aggression, but did so over the vehement 700-page dissent of the Indian Judge Radhabinod Pal, who condemned the notion of crimes against peace as retroactive, imprecise, and partisan—in short, a law concocted by Western lawyers to entrench a status quo established by centuries of Western aggression. For Pal, Western jurists repudiated the sovereign right to wage war just as non-Western states were learning to benefit from its invocation.

The twelve “successor trials” staged by the American military in Nuremberg (together known as the Nuremberg Military Tribunal, hereafter NMT), further spelled the demise of the idea that aggression constituted the paradigmatic international crime. Crimes against peace appeared as a formal charge in only four of the NMT’s cases—the IG-Farben trial (Case 6), the Krupp trial (Case 10), the Ministries trial (aka, the Wilhelmstraße trial, Case 11), and the High Command trial (Case 12). Crimes against humanity, by contrast, appeared as a charge in all twelve of the NMT’s cases. More dramatically still, the narrative of Nazi atrocity that emerged in the successor trials differed quite dramatically from the IMT story. For example, in the Einsatzgruppen trial (Case 9), SS exterminatory practices no longer appear as simply an extreme instance of the general horror of Nazi aggression. Rather, in this trial we begin to detect the very lineaments of the understanding that would be fully expressed years later by Karl Jaspers: the extermination of European Jewry is treated as a crime sui generis—a crime so extreme it volatizes conventional categories of criminal wrongdoing and threatens to upend classic understandings of the normative significance of the Western nation-state.

This essay is adapted from Lawrence Douglas’s Aggression, Atrocity, and the Verbrecherstaat, a book in preparation under contract with Princeton University Press.

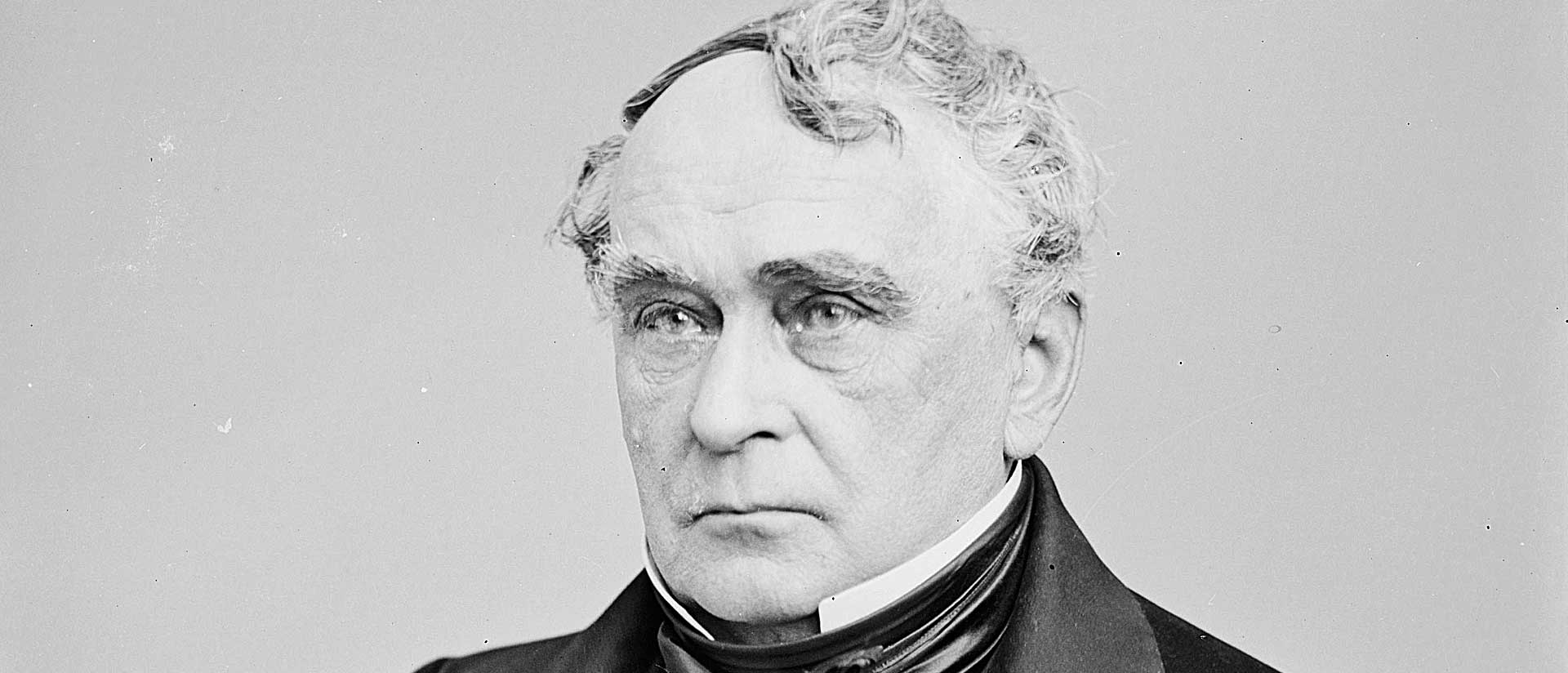

Photo: Justice Robert H. Jackson delivering the opening statement at the Nuremberg Trials, November 21, 1945. Photo: Ray D’Addario. Courtesy Nuremberg City Archives (StadtAN A65/ III / RA-204-D).