Sarah Bernhardt’s Knee

Feminine “respectability” on the Brazilian stage

By James N. Green

Turn-of-the-twentieth century Rio de Janeiro was the bustling capital of the newly established Brazilian republic. Slavery had been abolished in 1888, and 14 months later, the 67-year-old empire had toppled. Tens of thousands of freed people of color sought work in Rio, and tens of thousands more Portuguese and Italian immigrants crossed the Atlantic to seek new opportunities in the tropics.

While enslaved and working-class women of color occupied public spaces in Brazil throughout the colonial period and during the Empire (1822–1889), among middle-class women, new opportunities and possibilities only opened up in the later half of the nineteenth century. By the end of the century, the majority of primary-school teachers were women. Middle- and upper-class women had broken into the legal and medical professions. Women also produced a flurry of feminist journals and initiated campaigns for equal rights, including the right to vote.

Some women took to the stage. The acting profession afforded a handful of Brazilian women freedom and independence unusual for the elite or bourgeois milieu. They could frequent public spaces, move about relatively freely, and enjoy a life unfettered from familial restraints. The theater also offered some adventurous and free-spirited white women, especially those from humble backgrounds, upward mobility and access to men of other social classes. Yet, because of an association between women of the stage and loose morals, they occupied a tenuous liminal position in elite society. On one hand, high society embraced women who appeared in plays or operas representing high culture, European values, and sophistication. On the other hand, however, female performers could suffer public scrutiny and bitter gossip for leading unconventional lives. Through negotiating this complicated status as pariahs and as public performers, these women pushed outward the possibilities for women in a patriarchal and traditional society.

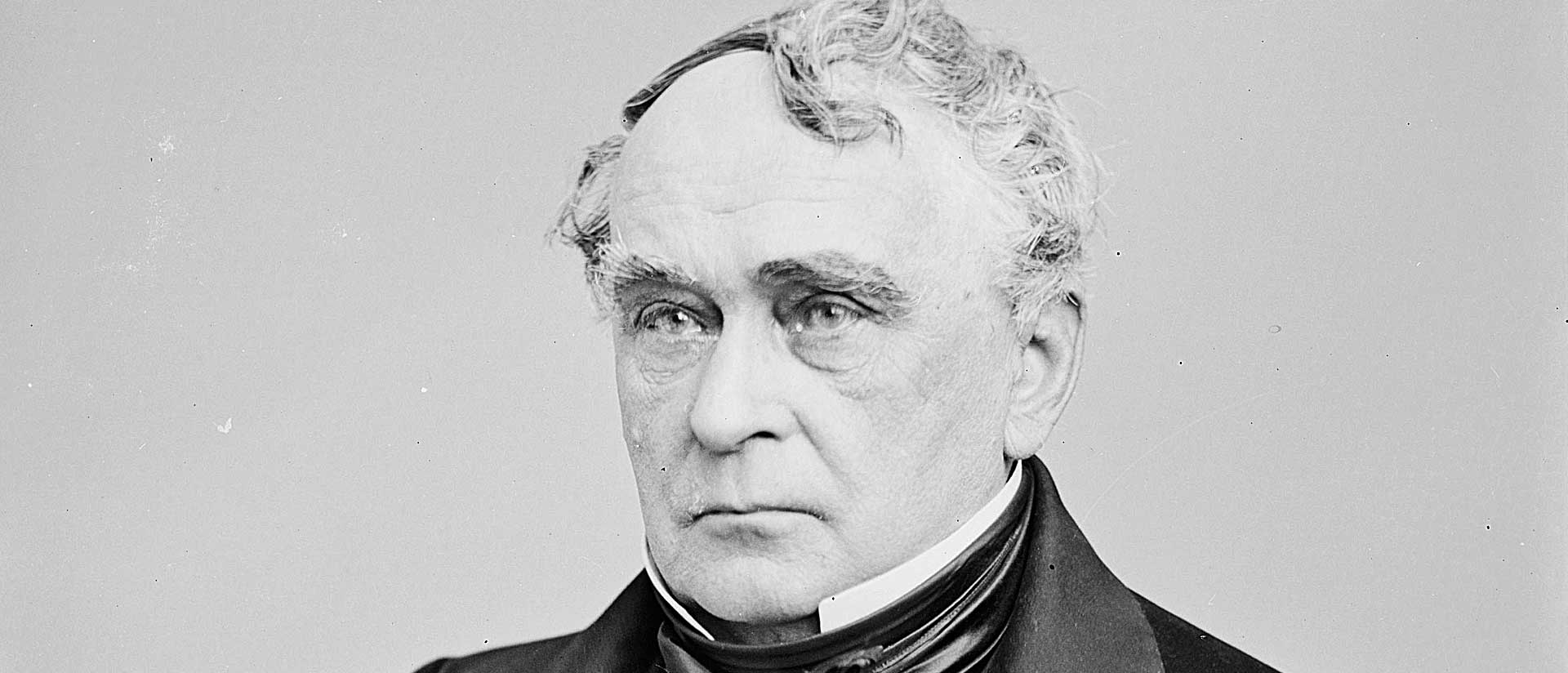

In 1886, Sarah Bernhardt, France’s preeminent dramatic actress, made her first of three South American tours. Three thousand people awaited her at Rio’s docks. Politician and abolitionist Joaquim Nabuco exalted Mademoiselle Bernhardt on the front page of O País. “In Brazil the great artist [. . .] is still in the intellectual territory of her homeland. In no other country will she better verify with precision that verse that one often hears on stage: All men have two countries, their own and France.” Having the “Divine Sarah” perform in Rio was grounds for praises doubly declared: “At this moment,” Nabuco wrote, “the first of all French theaters is not the House of Molíere but the São Pedro Theater.” Bernhardt’s visit to the imperial capital offered the elite the opportunity to experience firsthand noble French culture.

On opening night, confusion reigned. Police struggled to maintain order, and ticket scalpers offered exorbitant prices for available seats. Inside, the audience was composed of the “finest, most select, and intelligent families and gentlemen of society,” reported O País on June 3. They were joined by members of the French colony and the imperial family in attending a presentation of La Dame aux Camélias, one of Bernhardt’s signature performances.

Mademoiselle Bernhardt’s Rio debut, however, did not go as smoothly as anticipated. Students occupying the inexpensive seats began a ruckus when the actor portraying Armand Duval entered the scene. Commentators attributed the youthful rowdiness to the fact that the French actor was beardless and thus inappropriately matched to his manly, virile character. Adding to the commotion, a lighted cigarette from the second gallery fell on the evening dress of the Baronesa of Mamanguape, destroying her garment. The performance continued only because of the intervention of the famed playwright Arthur Azevedo, who stood up and demanded respect for the great French actress, and of the theater’s manager, who offered to refund patrons’ tickets. No need. By the evening’s end, Bernhardt had won over the audience entirely.

Bernhardt’s visit was marked by other incidents. Another actress in the French company accused Bernhardt of having slapped her during an altercation outside the box office. Bernhardt, never one to shy away from publicity, ended up at the police station, where the admiring politician Nabuco successfully defended her. Officials dropped all charges. At another gala performance, in Bernhardt’s honor, the audience’s enthusiasm seemed bottomless: having exhausted the stock of flowers that they showered onto the stage, the male public began to toss items of clothing. Her send-off was no less tumultuous, as hundreds bid their last adieu. A professor of the military academy delivered a farewell address and then presented Bernhardt with a Brazilian flag, which she dramatically draped over her shoulders, eliciting further adoration from the crowd.

Sarah Bernhardt was not the first French actress to elicit such enthusiasm in Rio. In 1859, French entrepreneur Joseph Arnaud opened the Alcazar Lyrique Theater, located near Rio’s fashionable shopping street lined with French-owned stores, restaurants, and cafés that targeted the sophisticated Francophile upper class. In 1864, Arnaud brought back from Paris a group of actresses, singers, and dancers to supply French entertainment to a Brazilian public. Many of these French performers, as it so happened, supplemented their income as prostitutes or as mistresses. Their embodiment of French culture increased their appeal over that of the polacas, the Eastern European Jewish prostitutes, or Brazilian sex workers of mixed racial backgrounds. On stage, they exposed their ankles, knees, or thighs, while singing such French hits as “Nothing is Sacred for a Soldier,” to arouse the interest of potential clients, among them many members of the Brazilian elite. As the can-can became popular entertainment for elite audiences in Brazil, dancers generously revealed their undergarments and normally hidden flesh to the excitement of the male audience.

Sarah Bernhardt was not the first French actress to elicit such enthusiasm in Rio. In 1859, French entrepreneur Joseph Arnaud opened the Alcazar Lyrique Theater, located near Rio’s fashionable shopping street lined with French-owned stores, restaurants, and cafés that targeted the sophisticated Francophile upper class. In 1864, Arnaud brought back from Paris a group of actresses, singers, and dancers to supply French entertainment to a Brazilian public. Many of these French performers, as it so happened, supplemented their income as prostitutes or as mistresses. Their embodiment of French culture increased their appeal over that of the polacas, the Eastern European Jewish prostitutes, or Brazilian sex workers of mixed racial backgrounds. On stage, they exposed their ankles, knees, or thighs, while singing such French hits as “Nothing is Sacred for a Soldier,” to arouse the interest of potential clients, among them many members of the Brazilian elite. As the can-can became popular entertainment for elite audiences in Brazil, dancers generously revealed their undergarments and normally hidden flesh to the excitement of the male audience.

What distinguished a proper elite woman in Rio from a French cocotte—a fashionable prostitute—was her public performance. University of Florida historian Jeffrey Needell writes in A Tropical Belle Époque that for elite men of Rio, “The cocotte’s attractions derived not only from studied association with Parisian paradigms but from the contrast they made with the perception of elite women.” When proper women from the Rio elite did go out, Needell writes, “there should be nothing of the cocodette about them. The cocottes’ style was well known, and one took pains to avoid it and to maintain the silence, respect, and company tradition demanded.”

In the eyes of her Brazilian audience, Bernhardt was not a cocotte. Although her personal life involved a series of somewhat public affairs, in Brazil her public persona linked her to French refinement and sophistication. By embracing Bernhardt as a serious dramatic actress, Rio’s elite reaffirmed their social status as connoisseurs of European culture. Although Brazilian men showered her with flowers and their garments, they received no exposed knees or undergarments in return. Proper women could attend and applaud her performance because her role as the conveyor of continental culture to a less civilized Brazil diminished any possible negative association with indecency, immorality, scandalous love affairs, and illegitimate children. Her performance on stage compensated for any moral transgressions committed off stage. Emperor Pedro II could receive and admire her. She could be the envy of elite society.

Six months before Bernhardt set foot on the Brazilian stage for the first time, Revista Illustrada published a two-page article entitled “The Eternal Feminine,” which heralded certain advances of middle-class and elite women. But these changes merited a certain caution. Citing expanding educational opportunities for Brazilian women, the newspaper noted, on January 16, 1886, “It’s time to verify if these educational means should be broadened; if women should be given rights and establish equality with men in carrying out certain positions.” Acknowledging that women were capable of entering many new professions and industries that had heretofore been occupied exclusively by men, society needed to hold the line at granting them political rights. Doctor or lawyer, perhaps, but voter or politician, never. The bello sexo, as journalists so often called women, may move into new occupations, but their beauty, elegance, and eternal femininity needed to remain in place.

In analyzing the New Women of turn-of-twentieth-century France, historian Mary Louise Roberts, in her 2002 book, Disruptive Acts, points to the strategy employed by certain women to “define a ‘personality’ apart from social convention—beyond their otherness to men—without getting trivialized or demonized by a set of stereotypes.” French feminist journalist Marguerite Durand, the editor of the all-female-staffed La Fronde daily newspaper, for example, carved out new spaces for women by embracing and then subverting many of the notions attributed to la belle sex. Her stunning beauty, blond hair, and elegant style undercut masculine criticism and deflected anxieties about the new realms into which the women reporters had stepped—the courtroom, parliament, and the political world. Using the age-old vision of woman as actress and seductress to counteract the stereotypical notion of feminists as shrill, ugly, masculinized man-haters, she caught her critics off guard and managed to fashion new possibilities for women by transforming seemingly traditional roles of women into something new.

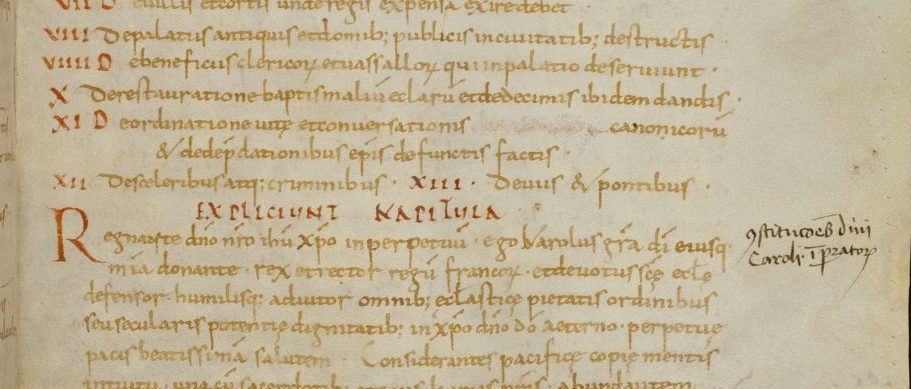

Likewise, Bernhardt made use of an array of tropes assigned to women to create a public personality that afforded her freedom, independence, and immense popularity at home and abroad. According to Roberts, “Bernhardt’s womanly woman would be immensely appealing to those men [. . .] who, lost in the turmoil of fin-de siècle gender relations, feared la grande séductrice to be an endangered species.” Even her famous cross-dressing roles such as Hamlet intervened in the tension between the traditional woman and the New Woman. Roberts argues:

In an era of debate about gender norms, Bernhardt’s star image presented a similar fantasy scenario that fulfilled a need on the part of her public for unity, resolution, and reassurance. To her more socially conservative fans, Bernhardt appeased fears concerning the threat of the New Woman and the demise of female seduction as an everyday pleasure. She transcended the perceived conflict between the independent New Woman and the séductrice. [. . .] [S]he was a living example of Marguerite Durand’s contention that a woman need not lose her femininity to compete in a man’s world. (p. 79)

Soon after Bernhardt’s first triumphal Brazilian tour, Cinira Polonio, the daughter of Italian immigrants, made her dramatic debut on the Brazilian stage, imitating the Divine Sarah in the musical review O Carioca, written by Arthur Azevedo. Following the conventions of the revistas de año, in which actors parodied prominent figures and events of the previous year, Polonio played an unspecified celebrity who spoke Portuguese in a thick French accent. Cinira reenacted an exaggerated version of Bernhardt’s quarrel with her fellow actress and made various references to the negative audience responses to the beardless Armand during the opening night of La Dame aux Camélias.

Of humble birth, Polonio’s entrepreneurial parents successfully managed a fashion shop in downtown Rio that allowed them to send their only daughter to study in Europe. Returning to Rio, she began her entertainment career in opera, but was not very successful. After her 1886 imitation of Bernhardt, Polonio became a popular actress, first in Rio and then in Portugal. Rather than trying to replicate Sarah Bernhardt, Polonio created a parody of mannerisms that were associated with European sophistication that poked fun at the French and Rio elites. Unlike Bernhardt, however, Polonio did not restrict her repertoire to plays consecrated by the elites as high culture. The limited audience for sophisticated European fare, and the growing urban market seeking popular entertainment, drew her to lowbrow musical comedies. Her performance at age 51 as an elegant francesa won rave reviews. Her playful French accent and her piquant double entendres thoroughly amused the lower- and middle-class audiences. Her imitation of the sophisticated French woman no doubt also played with a certain disdain that the popular classes experienced toward the haughty airs of Rio’s elite, who indiscriminately embraced all things French. Like many other New Women of her time, she learned how to manipulate male images of the feminine to her advantage. She appropriated and incorporated the exaggerated elegant feminine French figure into her stage performances, while off-stage she refused to marry and became a successful theater entrepreneur. Like the Brazilian modernists three decades later, she borrowed and reshaped (or cast off) elite foreign cultural norms and created something uniquely Brazilian.

Sarah Bernhardt returned for her third and final series of performances in Rio in 1905. She was, however, not well. Her right knee bothered her, and she walked, painfully, with a cane. According to several biographers, she suffered an accident in Rio that affected the rest of her life. Biographer Joanna Richardson writes, in Sarah Bernhardt and Her World (1977):

“On 9 October, at Rio de Janeiro, she met with one of the great disasters of her life. She was playing in La Tosca. At the end of the last scene, Floria committed suicide by leaping off the parapet of the Castel Sant’ Angelo. Usually, of course, the stage behind the parapet was covered with mattresses; that night, for some unknown reason, the mattresses had been forgotten, and Sarah fell heavily on her right knee. She fainted with pain; her leg swelled violently, and she was carried to her hotel on a stretcher. Next day, when she embarked for New York, a doctor was called to her stateroom, but his hands were so dirty that she refused to let him touch her. In vain, her friends protested and insisted they would make him take a bath. Sarah would see no doctor until she reached New York three weeks later.”

The knee injury ultimately led to the amputation of Bernhardt’s leg, forcing the Divine Sarah to perform during her final years with a cork substitute.

When I began doing research for a project about Bernhardt and the urban life of Rio at the turn of the century, her knee incident seemed to me the perfect illustration of her dual personae. While the elite male audience could enjoy the knees, thighs, and undergarments of French entertainers, the public performance of Bernhardt or of any Brazilian actress who aspired to her theatrical heights required propriety and decorum on stage and a modicum of discretion off stage.

Yet oddly, when reviewing Brazilian newspapers, I found no reference to the knee incident. To a certain extent, this made sense. Supposedly the tragedy occurred in the last act of Bernhardt’s last performance, October 9, 1905. But the dates didn’t match. Bernhardt first arrived in Brazil on October 10, 1905, a day after the alleged accident. Her last performance in Brazil was on October 17, in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, where presumably her knees were indeed exposed to the audience, albeit covered by tights. In Europe, Bernhardt had played the role of Floria in the dramatic version of Tosca, but there is no indication that she performed the piece during her tour. In fact, the same night as Bernhardt’s farewell rendering of Hamlet, at the Lyrico, Senhora Jacoby and Mario Cavaradossi gave their last performance of Puccini’s Tosca at the Apollo Theater, several blocks away.

What does one make of this? Were Bernhardt’s biographers wrong with details but right about the incident? Or was Bernhardt engaged in myth-making, presenting herself as the tragic heroine of Tosca, who so thoroughly played her part that she injured herself permanently? Wasn’t self-re-creation and the public performance of a series of expected personae an essential element in these actresses’ lives, as they constantly battled offstage for relative independence and freedom as adventurous and free-spirited women in a society still hostile to such behavior and inclined to immediately classify them as immoral? If Bernhardt did, in fact, re-create herself as a tragic heroine, sacrificing herself or her leg for her art, it is hard not to see her as also creating a larger than-life figure that could withstand the social and moral aversions to her “real life” or off-stage performance as a “new woman.” □

Image: Sarah Bernhardt as Hamlet, 1899. Layfayette Photo, London. Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons