The Andrew W. Mellon Workshops

With generous support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the American Academy in Berlin established the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship in the Humanities to advance the research capacity of the Academy and to strengthen collaboration between the US and Germany at both individual and institutional levels.

The Mellon Foundation is funding two fellowships each year, in an initial three-year commitment, for projects on the topics of migration and social integration, race in comparative perspective, and exile and return. In addition to the public lecture or other events offered by the Mellon Fellow while in residence, the Academy also convenes a weeklong, interdisciplinary workshop in January (for the fall fellow) and in June (for the spring fellow), thereby enhancing transatlantic dialogue and networks. Approximately a dozen workshop participants also take part in a public event, hosted in cooperation with an institutional partner. We are grateful for the myriad contributions from the Institute of Cultural Inquiry and the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, who hosted the public workshop events in our inaugural year of Mellon Foundation funding.

Workshop V: "Past and Future Genders: Latin America and Beyond" (June/July 2022)

The fifth Andrew W. Mellon Workshop at the American Academy in Berlin, originally scheduled for June 2020, took place from Monday, June 27, 2022, to Friday, July 1, 2022, and was chaired by Moira Fradinger, Associate Professor of Comparative Literature at Yale University. The workshop explored new paradigms and policies regarding issues of gender identity and politics emanating from Latin America.

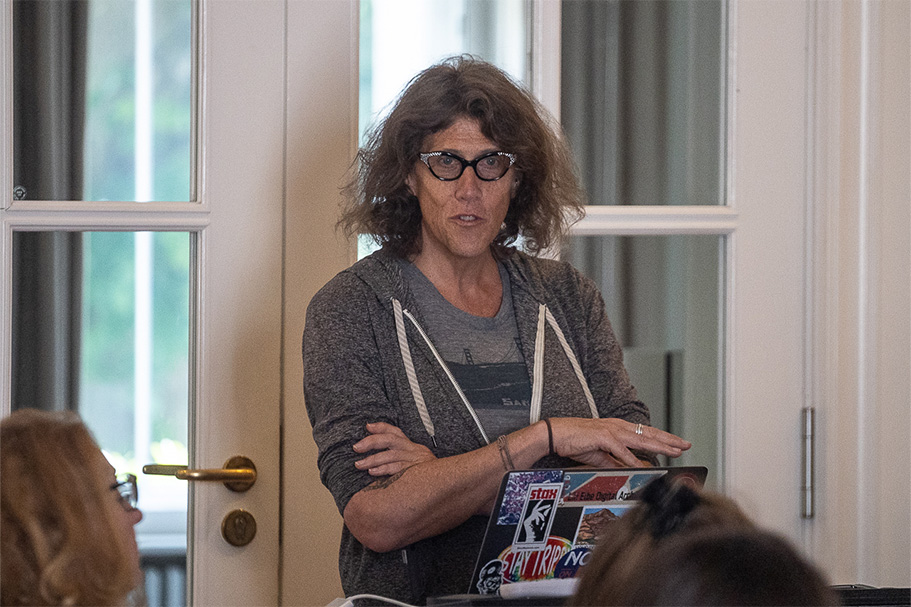

On June 30, an evening public event, “Trans: Here, Now, and Hereafter,” brought together Tamara Adrián, a trans lawyer, professor of law, and congresswoman in the Venezuelan National Assembly (elected December 2015), Julia Ehrt, the executive director of the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association (ILGA World), and Susan Stryker, an activist, professor of transgender studies, and currently the Marta Sutton Weeks External Faculty Fellow at Stanford University Humanities Institute. Together, they addressed how global ideas of gender are changing in the contemporary world and examine the ways in which “gender” can be understood as an artifact of the biocentrism that structures the modern Eurocentric worldview. The event was moderated by Moira Fradinger and Berit Ebert, Vice President of Programs, American Academy in Berlin.

Workshop IV: "Im/Mobilities: New Directions in the Humanities" (June 2022)

The fourth Andrew W. Mellon Workshop at the American Academy in Berlin, co-chaired by fall 2020 Andrew W. Mellon Fellow Laila Amine, Associate Professor of English and Global Black Literatures at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and spring 2021 Andrew W. Mellon Fellow Hakim Abderrezak, Associate Professor of French and Francophone Studies at the University of Minnesota, took place during the week of June 13-17, 2022. Participants shaped a broad transatlantic dialogue on the role of mobility in structuring global artistic productions in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Against a backdrop of unprecedented mass detention, refugee crises, deadly crossings from Africa and the Middle East, and the visibility of anti-black violence in the United States and Europe, panelists reflected on mobility in a large spectrum of genres that center on movements across seas, borders, and their afterlives. In a series of themed seminars, lectures, and roundtables, the June 2022 Andrew W. Mellon Workshop investigated new directions in the humanities with respect to current scholarship on mobility and immobility and related themes, such as race, citizenship, and belonging.

On June 16, Dominic Thomas, Madeleine L. Letessier Professor of French in the Department of European Languages and Transcultural Studies at the University of California at Los Angeles, moderated an evening public event, “Colonialism, Propaganda, and Postcolonial Legacies,” which was followed by a discussion with Hakim Abderrezak and Laila Amine. In it, Thomas examined and decoded various forms of colonial representation to better understand how iconographic propaganda was instrumentalized to legitimize and enforce colonial rule.

Workshop III: "Mixed Motive Migrations and the Implications for Public Policy" (January 2020)

The third Andrew W. Mellon workshop, “Mixed Motive Migrations and the Implications for Public Policy,” took place at the Academy from January 6 to 10, 2020, chaired by Roberto Suro, a professor of journalism and public policy at the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism and Price School of Public Policy at the University of Southern California. The workshop addressed current migration phenomena and their impact on destination societies. It also reconsidered longstanding assumptions behind immigration politics and policies. Participants also addressed specific formulations of humanitarian obligations and national interests as well as new strategies that connect the two in convincing and meaningful ways. Comprised of a dozen scholars from the US and Europe, the Mellon workshop brought together distinct academic disciplines and differing methodological approaches to issues of migration. Also in attendance were a number of Berlin-based scholars, policy experts, and nonprofit representatives, who were invited as workshop guests to broaden the discussion on US-German similarities in migration mechanics, policy challenges, and political responses.

A public panel entitled “Responses To Humanitarian Migrations: A Transatlantic Conversation” was held on the night of January 9 and assessed some of the lessons learned from recent migrations out of Central America, the Middle East and Africa. Panelists also looked at alternative courses of action for countries such as the United States and Germany when contending with the sometimes sudden, sometimes large-scale but inevitable arrival of displaced persons seeking a new home. The panel included T. Alexander Aleinikoff, director of the Zolberg Institute on Migration and Mobility and The New School; Thomas Bagger, Director-General for Foreign Affairs at the Bundespräsidialamt; Naika Foroutan, director of the Deutsches Zentrum für Integrations- und Migrationsforschung DeZIM e.V.; Julia Preston, a visiting research scholar and visiting lecturer in the program in Latin American studies at Princeton University, and the Academy’s Mellon Fellow and workshop organizer Roberto Suro. The panel was moderated by Anna Sauerbrey, of the editorial board of Der Tagesspiegel.

Displacement Migrations and Implications for Public Policy

Introduction by Roberto Suro

Professor of Journalism and Public Policy, University of Southern California

During the decade of the 2010s the United States, Germany and other rich democracies struggled with immigration crises. Migrants arrived at borders unbidden seeking entry with asylum claims that told of violence and economic misery in their homelands. From the Aegean to the Rio Grande they made crossings sometimes suddenly and in large numbers. Uncounted thousands drowned in the chaos. Border control forces appeared impotent. Elaborate immigration policies collapsed in the face of unanticipated challenges. Demands for a crackdown and undisguised xenophobia fueled the rise of populist nationalism in nations with widely differing political cultures, most notably in the United States where Trumpism reigned after the 2016 elections.

Days after the decade’s end the American Academy in Berlin hosted an eclectic collection of thinkers from both sides of the Atlantic for a series of conversations that grappled with the meaning of these events. It was the first week of January 2020, and the COVID-19 pandemic was still incubating. For five days at the Hans Arnold Center, the Academy’s lakeside home in Wannsee, the discussions ranged from the impact of Artificial Intelligence on the demand for immigrant labor to the impact of trauma on children forced to flee their homes. Lessons from a decade just passing were projected on to a decade just beginning.

“Displacement Migrations and Implications for Public Policy” was the title of the workshop, the third in a series supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and in this instance conducted with the collaboration of the Tomas Rivera Policy Institute at the University of Southern California. The participants brought expertise gained in government, universities, journalism, philanthropy, business, civil society organizations, and the arts. Eight who traveled from North America were present throughout, and another 15 from Berlin and elsewhere in Europe came for various segments of the workshop. As director of the workshop, I assembled the invitation list with an eye to diversity across multiple attributes—professional experience, personal histories, interests and points of view.

“The goal of the workshop is to provoke thinking and conversation, and the program has been designed to move us towards deliberation and conclusions about the future,” is what I advertised to the participants. There were no lectures or PowerPoint presentations. Each session had a theme. Two or three of the participants were designated to give some framing thoughts at the onset, and then the dozen or so people sitting around the table went to work. “We want to reflect carefully on the realities of our age, and especially the experiences of the decade now ending as prelude,” the missive continued. “My hope is that reflection will move steadily into the realm of conceptual frameworks, vocabulary, policy structures, norms and political orientations, challenging the status quo and pressing for alternatives.”

None of us who gathered that first full week of 2020 could have imagined how thoroughly COVID-19 would upend every form of human mobility within just a few months. Without claiming any gifts of prophesy, however, much of the discussion took up themes not only still relevant but now even more urgent in the world remade by the virus. Below you will find edited introductory remarks of several workshop participant on the topics of options for the selection and control of humanitarian migrants; the child as migrant; the evolving relationship between migrants and host societies; and the geopolitical forces shaping the future of migration.

Options for Selection and Control of Humanitarian Admissions

Remarks by Martin Ruhs

Chair in Migration Studies and Deputy Director, Migration Policy Centre, European University Institute, Florence, Italy

What do Europeans think about asylum and refugee policies, and what does that mean and what should that mean for policymaking? First of all, over the past few years we have seen a very wide range of different proposals for how to reform asylum and refugee policies in Europe. Some people in some member states are arguing we need a stronger Europe, including mandatory reallocation of refugees or even asylum-seekers among EU member states.

Others are firmly rejecting that, focusing much more on border control. The Prime Minister of Austria, when you ask him, what’s one of your biggest achievements over the past few years? He says, I’ve helped convince other European governments that we should stop talking about mandatory reallocation.

It’s not even that obvious anymore that everybody accepts the Geneva convention as the one guiding principle or associated international norms. So what should be the criteria that we use to evaluate competing reform proposals? To what extent is it important to maintain all aspects of the Geneva convention? That’s an important debate.

I also think we need much greater realism in some of these debates. There’s a temptation nowadays to say that the system is broken, we need paradigm change, something completely different. Under that kind of rubric, we have proposals for disembarkation centers, for external processing. Well yes, let’s have a debate, but let’s be realistic. What countries would be able to provide these processing centers? What are the incentives?

It’s important to understand much better what public attitudes are in this policy area. To what extent should policy respond to public attitudes in this area, which is clearly, and should clearly be driven by important moral and legal considerations? There’s surprisingly little research on this.

We’ve looked at eight European countries, and asked 12,000 people about the types of asylum and refugee policies they would prefer.

Basically we find that Europeans do want to provide protection to asylum-seekers and refugees. It is not true that across Europe you have this preference for getting rid of asylum, for bringing resettlement to zero, for providing no family reunification. Actually, people don’t like policies that deny family reunification to refugees altogether. But there’s a strong preference for policies that include limits and conditions.

So, just to give examples. There’s strong preference for using annual limits on the number of asylum-seekers coming to the country. There’s also strong preference for regulating family

reunification for refugees through a requirement which basically says that you have to provide for the living costs of the incoming family members. This is very common in labor immigration policy, much less common in asylum and refugee policies for the simple reason that many asylum-seekers who get accepted will not actually have the financial means to support their incoming family members. When it comes to financial assistance to non-EU countries hosting large numbers of refugees: Yes, Europeans want to give, but on the condition that these countries help reduce the number of migrants coming to Europe.

We know that in asylum and refugee policy, there’s always a tension between providing protection and maintaining some sort of control. On non-refoulement, we actually found that if you have a policy that violates the principle of non-refoulement, people don’t like it. That reduces support. But the basic point is there seems to be a strong preference for using limits and conditions.

So a second question is, what are the factors that drive these preferences? A very important concept in this debate is political trust, the trust that people have in political institutions.

Specifically, we find that people with high trust in EU institutions, they do not demand these kinds of limits and conditions. People with lowe trust in EU institutions, their demand is greater for using these limits and conditions. The lower the trust, the less likely people are to support expansive asylum and refugee policies.

But what we find is that the question is not, “Do you support it or do you not support it?” It depends on the policy design. We find that if you have policies that use limits and conditions, even people with low political trust can come around to supporting your policy. Because basically they will say, I have low trust in government institutions, so I need something else. That something else is limits and conditions in the policy provision.

In short, there seems to be a demand for limits and conditions. There’s no demand for getting rid of protection altogether. And these preferences do seem to be conditioned by people’s trust in European institutions.

This kind of research suggests that it really is important for the European Union and also our national governments to have some success stories in this policy area, to maintain trust. Another EU meeting that ends in acrimony and failure is not conducive to encouraging people to support asylum and refugee polices.

The Child as Migrant

Remaks by Jacqueline Bhabha

Director of Research, FXB Center for Health and Human Rights; Professor of the Practice of Health and Human Rights, Harvard School of Public Health; Jeremiah Smith Jr. Lecturer in Law, Harvard Law School

First, child migration is not new. Children have always traveled with their families, fleeing conflict or persecution, or moving for work and opportunity, or being forcibly trafficked by slave owners, religious orders, or warlords, on a massive scale, throughout history. Just think of the Irish potato famine, which was maybe an early environmentally induced forced migration that saw the relocation of large numbers of children.

Like women before them, when children traveled with families and in groups, they were largely considered appendages of the male householder. In that sense, they were irrelevant to policy and law, even if they weren’t completely invisible.

Secondly, children have also traveled unaccompanied for much the same reasons as adults: to escape persecution, join family, seek employment or other opportunity. And for children, as much as for adults, many of our dichotomies, including forced and voluntary, are best replaced by a spectrum of determinants, a spectrum that itself can change over time. You can go from being forced to voluntary and voluntary to forced within the same journey.

Historically, there have been made different types of unaccompanied child migration. Many of the earlier migrations were more organized than unaccompanied child migration is now. The Kindertransport comes to mind; the Pedro Pan children fleeing Cuba after Castro’s revolution. Today, by contrast, we’re seeing ad hoc large-scale migration, for example, of Afghan boys or Eritrean children to distant destinations in Europe. So that’s one type of unaccompanied child migration.

Another type are the tens of thousands of children who have traveled alone after they being so-called “left-behind children.” Just think of Filipino, South Asian, or Central American children, all traveling to join parents or other relatives who embarked on international migration without them, in some cases planning to be temporary or seasonal workers originally, in others intending from the outset to be permanent, but unable to afford to bring their children with them. For whatever reasons, that initial adult migration turned into a permanent relocation where parents wanted to include family. And so, children traveled to join but often traveled alone.

Thus, the first point is that this phenomenon is not new.

Is the scale new? I think it’s difficult to confidently assert that the numbers of child migrants have dramatically increased, because we have very poor longitudinal data. According to the best data, the share of global migrants under 20 in 1990 was 18.6 percent, and it dropped in 2019 to 13.9 percent. In terms of the share of migration, it would certainly not be accurate to claim that we have more and more child migration.

But in terms of absolute numbers, the opposite is true. In 2019, there were 37.9 million migrants under 20, up from 28.4 million in 1990. A huge increase.

Now, behind these aggregate figures are enormous regional differences. It’s tempting but actually misleading to overgeneralize. Asia has experienced the sharpest increase in the absolute numbers of young migrants. But in terms of proportion, in Africa, 30 percent of migrants are children, compared to less than 10% of migrants in Europe or North America. And even though children are less than 10 percent of the overall migrant population in Europe or North America, there have been very large numbers of recent arrivals. In 2015, 31 percent of refugees arriving by sea in the European Union were children.

So, child migration is not new. Numbers? Difficult to say. What is new is the narrative—the political and the policy attention to this issue.

Think of the case of Edgar Chocoy, a Guatemalan child who applied for asylum in the US, was refused, sent back to the country he had fled, and then murdered the next day by a gang. He became a cause célèbre. The fate of child migrants has captured public attention and public compassion in a way that their adult counterparts often have not. Child migration, one could suggest now, is the poster child of humanitarian claims, not its neglected subplot. Why has that changed?

One possible reason is the global information commons, which beams images into millions of homes instantaneously: babies being handed off boats as they come ashore in Lesbos, children walking barefoot in the snow in refugee camps, children ripped crying from their parents at border check points. We see these scenes in real time, and they pull at your heartstrings.

In part, it is the organization of social media, which child migrants themselves rely on, which makes them much more effective agents. We know this, for example, about the migration of Afghan boys to Sweden. They didn’t intend to go to Sweden when they fled the Taliban at home, they just found out en route that Gothenburg was the place to go to. It’s where you have really good child shelters, and they tell you they have generous policies. So, they navigated their way there. All of a sudden, Sweden has 37,000 unaccompanied minors.

The image of Aylan Kurdi was a watershed in the expression of humanitarian compassion in Europe. It didn’t last, but it was a major driver. Images of Central American toddlers clinging to their parents’ legs, or wailing in detention centers, generated an unprecedented bipartisan uproar that rather speedily reversed Trump’s family-separation policy.

This narrative switch has coincided with some significant policy changes. Twenty years ago, there weren’t broad policies dealing with child migrants or child asylum-seekers. Today, in both what you might call the Caribbean basin and the Mediterranean basin, there are official policies covering child migrant reception, conduct of child asylum claims. Immigration personnel receive training on migrant-specific matters, so do judges and adjudicators.

But, of course, these progressive guidelines haven’t always translated into better conditions, because of the second innovation: immigration externalization. We are seeing situations, in the Americas and in the Mediterranean area, where, despite an awareness that children have agency and have rights, responsibility for affording them protection is being externalized. Externalized from the US into Mexico, externalized beyond the southern border into Guatemala and beyond. Externalized from Europe into Libya, and then returned in large numbers to Sub-Saharan Africa.

We, as a global polity, may be more aware of our collective humanitarian obligations under international law, not just the Refugee Convention, but also the Convention on the Rights of the Child. But we haven’t been able to translate the obligations we’re aware of into binding policy and practice.

That said, our understanding of the nature of child migration has become more differentiated. There was a stage where government decision makers as well as child migrant advocates lumped all children, particularly unaccompanied children, into one legal category. They were all trafficked, or they were all asylum seekers by default nearly. And now we have a tool kit which is much more differentiated. It’s a positive development.

Also, we are much more aware of the agency of children. When I talk about agency, I’m talking about teenagers. Afghan unaccompanied teenagers in Sweden demonstrated against their deportation for weeks in the central squares of Stockholm and got Swedish law reversed in terms of their right to stay. In the US, the militancy and impressive political leadership of the Dreamers, children brought without a legal status to the US as children, has thrust the issue into the political center stage.

To conclude, we haven’t managed to translate our understanding of the best interests of the child, or of the right to child-specific asylum, into effective protection. Migrant and refugee children are still largely excluded from domestic child protection and child welfare systems, a clearly discriminatory situation. Large numbers of children are still unable to access basic human rights, such as primary education, healthcare, including mental healthcare, safety. And as a result, because they can’t access a place of safety, many children are using self-harming strategies devised by themselves to facilitate movement from an unsafe place to what they think might be a safer place.

We did a study in Greece that documented an apparently common phenomenon: children selling sex to get money to pay smugglers to continue their journeys. This exploitative situation exists not only in Greece, it’s also common in other parts of the European Union. A clear result of our failure to create a protective environment.

The primary obligation facing polities intent on protecting the rights of children and young people trapped in dangerous and exploitative migration contexts is to enhance the entitlement to legal migration routes for young people. It shouldn’t just be privileged rich kids who have the chance to study abroad or have internships or skill development opportunities. We should be thinking about the obligations we have as a global commons towards the many, many young people who are thirsty for and fully merit the educational opportunity that some of us take for granted.

The Evolving Relationship Between Migrants and Host Societies

Remarks by Naika Foroutan

Director, Deutsches Zentrum für Integrations- und Migrationsforschung DeZIM e.V., Berlin

According to the numbers, Germany is a diverse society. It has 83 million inhabitants. The latest numbers say 21 million of them have a migration background. Every fourth resident in this country is either an immigrant or the German-born child of an immigrant. Nonetheless, this is a country that is still very much in the process of finding ways to talk about its diversity. Yes, we’ve had migration at different moments since the end of World War II, and there has been lots of conversation about who should get in and who shouldn’t, but we did not start to have serious talk about the immigrant role in Germany, about people who stay and become part of our society until much more recently.

It was only in 2006 that we had a first summit a so called “Integrationsgipfel,” where we first put up some kind of measurements, some kind of ideas of who is who, who belongs, what does it mean to be a German, who is a German, how does this migration background allows you to become a citizen, if you are a citizen does this mean that you can claim to be German also? So we had a lot of new words like Migrationshintergrund, which replaced the word foreigner, Auslander.

Since then we have tried a little bit with hyphenated identities, which didn’t work so well. We have Russland Deutsche which works a little bit. But then we have Deutsch Turken, which is the other way round, and it really shows that these people will remain Turkish forever, because in the German case it’s always the second part of the word that defines the word itself. So, Russland Deutsche are Germans, but Deutsch Turken are Turkish. Even if they are here for third or fourth generations. So all these new wordings and names become difficult. And it is not just finding names for immigrants. No one knows how to express what it means to be German. The children of immigrants who are Germans by birth and upbringing do not know how to talk about the others, the Germans of native stock. That’s how we get Biodeutsche, which means ethnic Germans but in a very ironic way. It is used very much by young people along with other words that are not so nice, like Kartofel, or like Almans, which is very a la mode now. What is really interesting in these names is that you see in them a changing society, becoming diverse, becoming different in its naming procedures, but not having the vocabulary to name itself.

Not surprisingly, we do not have narratives either. We do not have narratives for the counter reaction that migration is causing. We’ve discovered that our explanation toolbox is insufficient. We tried at first to explain this migration crisis or the harsh rise of the Right-wing populist parties with structural or economic arguments. This is something we tried for quite a long time. We said the Right wing is rising because we have such a high level of inequality. But then we look at countries like Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, all those countries with a rising Right-wing populist party, and on macro level they are doing all very well economically. So, something doesn’t work here. This idea of “It’s the economy stupid” is not really sustainable.

It is also not about the numbers. Take Poland. Only 12,000 asylum claims, but Poland has a harsh anti-immigrant party. The funniest thing for me is Slovakia with 145 asylum claims against a population of 5.5 million. Okay, it’s a small population, but just 145 asylum claims. I remember a Slovakian prime minister saying, “I do not wish there were tens of thousands of Muslims coming to our country, we do not want to change the traditions of the country.” Change traditions with 145 people? So, no it is not about the numbers.

Although it seems that this moment of fear is predominantly framed around migration, it is not. Migration has become a code for more than immigration itself. It is a code for rising pluralization and heterogeneity. So, if people are against migration, they are also against gender plurality. They are also against the European Union. They are also against cosmopolitan matters. They are against every visible form of pluralization. And there we can see that this draws a new bipolar line into societies. It’s no longer so much about right and left. And it’s not so much about age groups, young people versus old people. It’s mainly about those who can accept or deal with plurality and others who fear pluralization.

We did a study two months ago with 8,000 respondents, because we wanted to dig a little bit deeper into this pluralization issue. And we asked people about pluralization, but without connecting it to immigration. Saying things like, “I don’t like to hear so many languages in my town. I don’t want my supermarket to sell so many different kinds of food. I don’t want more than two sexes.” Just things that argue with pluralization and we could see a strong correlation between those who see plurality and those who are then against immigrants. The data lead us to consider that this migration has become a metanarrative for pluralization, and maybe it is just so much connected to migration, because migration is the most visible form of pluralization.

The reaction to migration reflects an evolving relationship between migrants and the host societies, and the ways that relationship evolves reflects on the fundamental promise of a pluralist democracy. That fundamental promise is of equality. Western democracies promise the social and political ascent and rights of all people, and now in the post-migration relationship we can see the rise of formerly underprivileged groups into power. Those people, former migrants, former outsiders, now residents in our societies, now fully embedded in our societies, know that there is another life, and they know that they can claim it.

The reason why those 25 percent of society who live here with a migration background, know their rights is because for the past 20 years democracies have been very good at proclaiming their ideas, selling their ideas out to the European Union, to the others who haven’t been part of the European Union, and selling to Afghanistan and selling to Iraq, and selling to other Muslim countries. Saying, “Look at us, look at our democracies, look at how powerful we are.” And the other people start to know. They know what this promise means.

But if you have this promise, how come, if 40 percent of the children of this country have a migration background, only 8% of the teachers have a migration background? How come none of our ministers of state has a migration background?

So, this gap between the promise of democracy on the one side and the empirical reality of inequality is something that we are facing now, and this is maybe one reason for the crisis. And we know that those people, those children in the schools, those 75 percent, the new normality in Frankfurt is no longer willing to accept this position. And by them entering into the arena of equality, we see these harsh anti-reactions. So, it is, I think, maybe about this promise of democracy clashing with the empirical inequality and this is something which is somehow seen in the favor of the immigrant.

Geopolitical Futures: What Does the World Have in Store for Migration?

Remarks by Marcelo Suárez-Orozco

Wasserman Dean, Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, Distinguished Professor of Education, Co-Director, Institute for Immigration, Globalization and Education, UCLA

Migration is written in our genome, it’s encoded in our stereoscopic vision, in our central nervous system, in our bipedalism. Migration is foundational to the human journey.

Migrations, of course, antecede nations and states and laws and frameworks by millennia. Ironically, many, many nations—Argentina, Australia, of course, the US, Canada, and so many others—structured the narrative of the nation around the idea of how migration came to make the nation state in its present form. So how has something that is so central to both the constitution of our history as a biological species and the history of the unfolding of so many nation states become fundamentally radioactive?

At any given time over the last five generations, really 2.5 percent to 3 percent of the world’s population is on the move. How does migration become a fundamental threat to the liberal democratic order and emerge as such a divisive set of preoccupations today, really, in nearly every advanced post-industrial democracy in the world?

At the end of his life, in the very last interview Freud gave, he was asked a famous question. “Professor Freud, what is your formula for a happy life?” The answer, of course, were two simple words, “love and work.” Love and work—but also war—really explain most human movement throughout most history.

Immigration in its original sort of conceptual iterations was framed as a labor phenomenon. We developed a framework—this isn’t landing a rocket on the moon—that labor migration begat family reunification, which begat the transnational chains, which begat the rise of the second generation as a kind of dominant set of concerns, and changed the conversation from labor to the cultural and social transformations that flow from the arrivals of significant numbers of new immigrants and their children. So, love and work still remain very, very powerful: family reunification, and work, of course, wage differentials drive a great deal of the movements of people.

Increasingly, demographic asymmetries are at the center. Other than Africa, the Middle East, Europe, the rest of the world is moving towards a very significant demographic decline.

Another set of questions I’d like us to think about is the role of unchecked climate change and environmental malfeasance in the forced displacement of peoples. We have entered the Anthropocene, the moment when human activity on the planet is creating spectacularly complex environmental climate changes that are impacting most directly, of course, the production, distribution and consumption of goods and services, broadly speaking, the economy. Syria is Exhibit A, where climate change, war, and terror are center stage. Syria today is, of course, the source of the largest forced movement of people in the world.

So love and work and war, unchecked climate change, and the rise of the second generation will continue to define migration moving forward. Every advanced postindustrial democracy in the world today, the only sector of the population growing is the children of immigrants. Here in Berlin, 40 percent of the children that woke up this morning to go to schools come from non-German immigrant and refugee-origin homes. In the US, 70 percent of the children in Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States, come from immigrant-origin Hispanic homes.

With climate change, with weak, unstable states, is the crisis today really an immigration crisis, or is it a crisis of confinement? Today approximately double the number of those displaced by World War II, some 80 million people, are in a state of permanent limbo, stuck in nowhere places. Large swaths of Turkey, of Mexico, the islands of Australia have really become containment, confinement centers.

Maybe none of this is particularly new or particularly different. Climate change has always driven the movements of people. Los Angeles Basin, home now of the second largest population in the United States, was settled 10,000 years ago because of climate change pushing first peoples, native peoples, American Indians, into the coastal zones. I have been in this field for a very, very long time. My intuition is that a lot of what is new is not really true, conceptually, and a lot of what is old is not necessarily false.

Workshop II: "Phonographic Knowledge and the African Past" (June 2019)

From June 3 to 7, 2019, the Academy’s second Mellon Fellow, Ronald Radano, a professor of African cultural studies and music at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, chaired the workshop “Phonographic Knowledge and the African Past: Sonic Afterlives of Slavery and Colonialism.” (He delivered a lecture on this topic during the spring 2019 semester and wrote an essay for the Berlin Journal.) The interdisciplinary group examined the role of phonographic archives today in how we remember our past, how we think about African history, and how the topic is addressed in a transatlantic context. During visits to the Phonogram Archive at the Ethnological Museum and the Sound Archive of the Humboldt-Universität, the group also met with German counterparts.

On June 6, 2019, Radano moderated an evening public event, “Scratching against the Kaboom and Blare of Trumpets,” held at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt. South African composers Philip Miller and Thuthuka Sibisi as well as Rosalind Morris explored the music and sonic landscape created in collaboration with William Kentridge for the multimedia performance “The Head and the Load,” about the participation of African countries in the First World War.

Workshop I: "Double Exposures" (January 2019)

The inaugural Andrew W. Mellon Workshop, “Double Exposures: Resource Extraction, Labor, and Migration in Africa, Germany, and the United States,” organized by fall 2018 Andrew W. Mellon Fellow Rosalind Morris, a professor of anthropology at Columbia University, took place during the week of January 7, 2019. The workshop explored the realities and representations of work and migration associated with mining and natural resource extraction in Africa. (Morris delivered a lecture on this subject during the fall 2018 semester and published a photo-essay in the Berlin Journal.) Participants included interdisciplinary scholars, artists, and critics with a range of regional expertise focused on southern Africa, Germany, and the US.

The workshop explored the idea of the extraction of natural resources—from precious metals to fossil fuels—which resides at the core of a global drive to “recolonize” Africa. Although the organization of migrant labor within Africa was the keystone of much colonial administrative theory and practice, the displacement and radical unsettlement that they induced is rarely discussed in relation to the over-arching question of movement out of Africa today. Once again, Africa is the terrain on which new developments in the idea of the extractive economy are being elaborated—and once again this extraction pertains both to resources and persons, encompassing not only what some scholars term “accumulation via dispossession,” but also the reification of bodies and the commodification of labor. Migration and conditions of prolonged displacement (and opposition to them) have emerged as the most significant components of political discourse almost everywhere in the world, particularly in Europe and the United States, with Africa often imagined as a source of especially illegitimate migratory ambition.

This Mellon workshop thus sought to engage these three regions comparatively but also according to the histories of their triangulation, from the deep history in which Africa has figured as a source of value and scene for the elaboration of Euro-American race discourse to the current global economy with its flows of materials and persons. With regard to contemporary tensions, the workshop sought as well to move beyond the crisis-paradigm grounded in the opposition of involuntary refugees to willful migrants.

On the evening of January 7, 2019, ICI Berlin hosted a screening of Rosalind Morris’s film The Gamblers, which was followed by a conversation between the Morris and Philippe Leonard, the film’s video editor and 16-mm film artist.