Forest Run

From the seen to the seeing

by Leigh Raiford

“Freedom was a thing that shifted as you looked at it, the way a forest is dense with trees up close but from outside, from the empty meadow, you see its true limits.” – Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad (2016)

The photograph is dark, layers of black and gray and more black, its subject nearly indiscernible. In fact, you probably can’t see much in the reproduction that accompanies this so you’ll just have to trust my description. A tangle of thin tree trunks populates the entirety of the photograph. They root below the bottom edge of the frame and reach above its top edge beyond our sight. The branches are mostly bare, having given up their leaves to form a blanket on the lower third of the photograph. Some leaves cling to branches, a blurry cluster in the left foreground, at the top they appear as splattered watercolor droplets, or tiny exploding black stars.

Dawoud Bey’s Untitled #17 (Forest) is a photograph of a dense forest in late autumn. But it is so redolent with darkness that it defies the very ontology of photography— writing with light, the index referent of what has been. Instead, a gelatin silver print patiently overexposed in the darkroom now ventures toward an abstractionist painting, a rendering of twisting black lines that form dark networks. It is not clear if those networks are there to impede or facilitate our movement. It is not clear that there is a path out, but when we move and sway in front of it, we find just enough light. It is dense but not impossible. I just have to trust that there is a way through.

Untitled #17 (Forest) is one of 25 images that comprises Bey’s Night Coming Tenderly, Black (NCTB). This 2018 series of large (44 × 55 inches) black-and-gray photographs of the outdoors in and around Cleveland, Ohio, is Bey’s rendering of “the sensory and spatial experience of fugitive slaves moving through the darkness of a pre-Civil War landscape— an enveloping darkness that was a passage to liberation.”

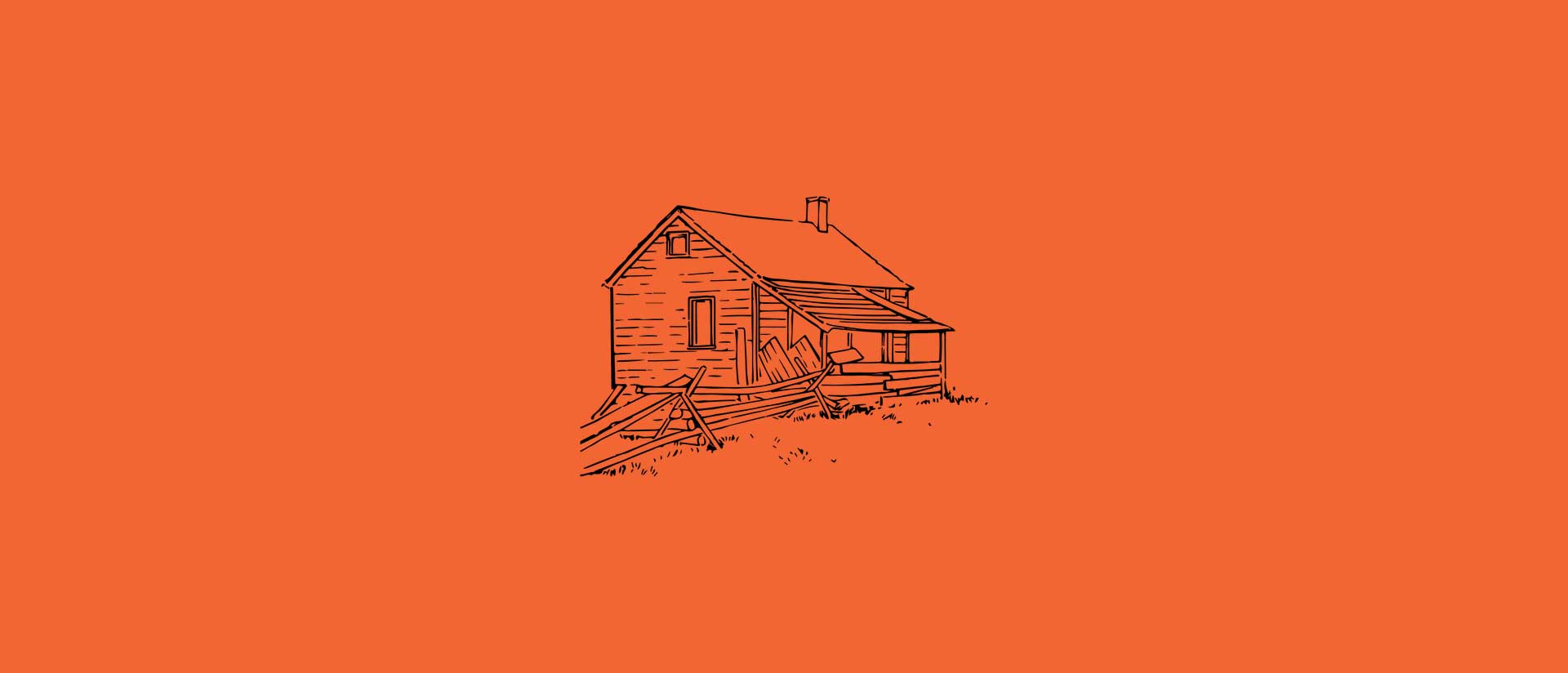

Ostensibly, NCTB is about “the past,” and Bey has reminded audiences that “the [photographic] language of history is black and white.” Black and white is also the visual telegraph of archival document. NCTB revisits and imagines stops on the Underground Railroad, the network of activists who aided fugitives’ perilous journeys out of the slave South. Bey emphasizes the blackness of black-and-white to offer an imaginative act of visualizing history that doesn’t feign verisimilitude. Indeed, the present announces itself immediately in the form of an air-conditioning unit that appears, like a blinking eye, at practically the center of the very first photograph in the series, Untitled #1 (Picket Fence and Farmhouse). And the present repeats by way of telephone wires (Untitled #3 (Cozad-Bates House), and a satellite dish (Untitled #18 (Creek and House). Lest we imagine ourselves too far removed from the hold—the plantation—NCTB reminds us that the time of slavery is also now. This part is not clever framing on Bey’s part; the present and the past coexist all around us.

Dawoud Bey, Untitled #17 (Forest), 2017, gelatin silver print, 111.8 x 139.7 cm. © Dawoud Bey. Courtesy: Sean Kelly

In its form, the series enacts the clandestine nature of the Underground Railroad, enhancing the darkness that protects the runaway from capture back into slavery; accentuating and reveling in the blackness that protects the wouldbe photographic subjects from overexposure and imprisonment in the camera’s luminous glare. In so doing, Bey upends the movement from the shadow to the light as the teleology of representational progress.

NCTB carves a path through so many of the visual conundra that have troubled the terrain of Black visuality. For Bey, long known and celebrated as a portraitist, NCTB refuses “photographic capture” through its shift to landscape. So too does NCTB refuse the affirmation of the self the genre of portraiture confers and confirms. There is no sitter in stasis, no subject either made regnant by or subjected to the sovereignty of the photograph. It is the loving, enveloping blackness of Roy DeCarava, one of Bey’s influences. It is the blackness of Glissant’s opacity. It is the blackness that Cedric Robinson, Teju Cole, and Tavia Nyong’o have each reminded us we can’t even yet imagine.

Dawoud Bey, Untitled #1 (Picket Fence and Farmhouse), 2017, gelatin silver print, 111.8 x 139.7 cm. © Dawoud Bey. Courtesy: Sean Kelly

From his first series Harlem U.S.A. (1978) to the Birmingham Project (2012), portraiture has been Bey’s primary mode of expression. It was Harlem Redux, the 2015 series imaging the rapid gentrification of Black Harlem, that marked a move away from the centrality of the human figure to convey Bey’s stories of people and place. Bey has acknowledged that Harlem Redux laid the groundwork for NCTB. But where Harlem Redux depicts an urban landscape saturated in color and devoid of people to convey an electric erasure, NCTB offers us fields, foliage, and waterways suffused in darkness and in subtle but constant motion.

Dawoud Bey, Untitled #3 (Cozad-Bates House), 2017, gelatin silver print, 111.8 x 139.7 cm. © Dawoud Bey. Courtesy: Sean Kelly

The move from Harlem Redux to Night Coming Tenderly, Black is a move from the enclosure to the outdoors; from confined and constrained spaces to air to breathe; from the ordered density of the city grid to “the uncleared and the overgrown.” It is a move from racial capitalism’s neon dystopic future to the “potential history” of the runaway and the maroon.

For me, the forest is a revelation, and also a cipher. In moving to landscape, Bey reminds us that Black folks both put their hands in the earth to build this nation’s wealth and were hung from trees for daring to live as though we belonged. So too does Bey assert the profound beauty and terror of the outdoors, and the uncertain pact fugitives made with these places as gauntlets to freedom.

Dawoud Bey, Untitled #18 (Creek and House), 2017, gelatin silver print, 111.8 x 139.7 cm. © Dawoud Bey. Courtesy: Sean Kelly

Neither past nor present, at once abstraction and figuration, both document and fiction. I can only describe Untitled #17 (Forest) as crepuscular, “of or relating to twilight.” We often think of twilight as the passage between day and night. But crepuscular names its own time and its own sets of behaviors—frogs croak out a song in round, fireflies dance bioluminescent in shifting light. So too do mice come to nibble at left-behind scraps and mosquitos search out blood to ensure their own survival. Untitled #17 (Forest) depicts the inexorable motion of the fugitive; it is a work of art that necessitates we take this time—so dense, so thick, so dark—on its own terms.

What if we choose, in the midst of flight (and fight), to linger here for a moment? To breathe together (which is the root meaning of “conspire”)? To listen for each other and all other things living and once living and still living? What if we share this quiet and let the darkness hold us, our secrets, and our dreams? Is this freedom? Is this home? □

“On the bed of damp earth, her breathing slowed and that which separated herself from the swamp disappeared. She was free. This moment.” – Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad

This article first appeared in the Berlin Journal 37 (2023-24).