The Mythology of the Sectarian Middle East

Divisions within, divisions without

by Ussama Makdisi

The term “sectarianism” is inherently elastic and ambiguous. It is used to denote pervasive forms of prejudice, historic solidarities, the identification with a religious or ethnic community as if it were a political party, or the systems through which political, economic, and social claims are made in multireligious and multiethnic societies. The term “sectarianism” is also used to indicate the favoring of one group over another, whether in hiring practices, renting, job allocation, or the distribution of state resources—that is to say, behavior akin to racial discrimination and profiling. “Sectarianism” is also used to describe sentiments that propel strident communal mobilizations, intercommunal warfare, and genocidal violence perpetrated by one group against another. Finally, “sectarianism” can also be thought of as a colonial strategy of governance insofar as Britain, France, Israel, and the United States have routinely manipulated the religious and ethnic diversity of the region to suit their own imperial ends.

Historically understood, “sectarianism” was first identified as a modern problem in the nineteenth-century Ottoman Empire and in the post-Ottoman Middle East at exactly the moment when the questions of equality, coexistence, citizenship, imperialism, and nationalism became salient around a European-dominated world. The advent of secular political equality did not go uncontested in any multireligious, multiethnic, or multiracial society of the nineteenth century. Recall that revolutionary France sought to re-impose slavery in Haiti after slaves there had liberated themselves, in 1804; the emancipation of enslaved blacks raised enormous controversy in the United States; and the defense of slavery was at the heart of its bloody Civil War. Jim Crow “separate but equal” segregation was legalized across the American South in the 1890s and was maintained until the mid-1950s. In Europe, modern racialized anti-Semitism followed the emancipation of Jews and found its most terrible expression in the Holocaust.

The Islamic Ottoman Empire (1299–1922), for its part, struggled with the question of the political equality of non-Muslim subjects. Under enormous European pressure in the mid-nineteenth century, the sultanate decreed a revolutionary equality between Muslims and non-Muslims. This shift was met with resistance—often described by historians as “sectarian” because unprecedented anti-Christian riots occurred in Aleppo and Damascus in 1850 and 1860.

But this political transformation of unequal subjects into supposedly equal citizens also produced the modern idea of “sectarian fanaticism” and as the antithesis to “true” religion and civilization. Whereas the former was seen as undermining national unity, the latter were at the heart of national modernization projects in the late Ottoman Empire and in the post-Ottoman Middle East. The concern with sectarianism in the modern Arab world thus does not simply indicate a political space contested by competing religious and ethnic communities; it also presupposes a shared political space. In this sense, rhetoric about “sectarianism” as insidious in the Middle East emerged in the late nineteenth century as the alter ego of a putatively unifying nationalist discourse.

Sectarianism is a diagnosis that makes most sense when thought of in relation to its ideological antithesis—much like racism in the contemporary United States: to identify and condemn racism in America, one presumably upholds an idea of equality and emancipation. To identify and condemn sectarianism in the Arab world, one presumably upholds an idea of unity and equality between and among Muslims and non-Muslims. For this precise reason, it was only in the early twentieth century, in Lebanon, that the Arabic term for “sectarianism”—al-ta’ifiyya—was coined, as a negative term in relation to national unity.

Sectarianism is a diagnosis that makes most sense when thought of in relation to its ideological antithesis—much like racism in the contemporary United States: to identify and condemn racism in America, one presumably upholds an idea of equality and emancipation. To identify and condemn sectarianism in the Arab world, one presumably upholds an idea of unity and equality between and among Muslims and non-Muslims.

The origin of this specific Arabic term emerged out of political debates about the nature of the post-Ottoman Lebanese state. More broadly, prominent intellectuals of the twentieth-century Arab world—Amin Rihani, Sati’ al-Husari, Antun Saadeh, Constantine Zurayq, Zaki al-Arsuzi, Edmond Rabbath, Munif al-Razzaz—all discussed sectarianism as a major internal impediment to modern development and sovereignty. A secret Arab society, which included Zurayq, was founded in Beirut in 1935 and developed branches in Syria, Palestine, Iraq, and Kuwait. It condemned “sectarian, racist, class, regional, tribal, or familial” solidarities that diluted and weakened “Arab solidarity.”

Nationalist intellectuals, in other words, recognized real social and economic problems within their societies, including that of sectarian affiliation. Yet, they also created a trope about sectarianism as a negative, reactionary holdover from a pre-modern age. In the 1950s, Zurayq, who was deeply opposed to mixing religion and politics, inveighed against “sectarian fanaticism” in evocatively modernist terms. He regarded sectarianism to be a problem “cascading from the past into the present,” and thus as an anachronism “in the age of nationalisms, and indeed in the age of the atom and space.” For him, sectarianism constituted the antithesis of an ideal of a secular, national modernizing state.

Even the Lebanese political elites, who created the first formal sectarian power-sharing government in the Arab world, accepted constitutionally that “political sectarianism” had to be a temporary measure (Article 95 of the Lebanese constitution). Proponents saw “political sectarianism” as a necessary evil until such time as the Lebanese people were able to cast off allegedly innate sectarian solidarities and embrace a modern secular Lebanese identity. Opponents saw “political sectarianism” as a disease bound to weaken, if not destroy, the national body politic. During the same mandate period, the great pan-Arab pedagogue Sati’ al-Husari established a secular national educational system in Iraq. He referred to his Iraqi detractors as sectarian. He believed that those who opposed his vision for a modern, secular Arab-nationalist Iraq under the Hashemite monarchy represented reactionary elements in society.

Despite this evident politicization and ideological framing, Arab understandings of “sectarianism” have often considered it both an internal and external problem. These interpretations have frequently connected internal “sectarian,” “tribal,” and “feudal” obstacles to progress and development with the reality of Western interventionism in the region. Throughout the twentieth century, citizens of the Middle East have been haunted not only by the possibility of internal fragmentation in their societies, but also by the prospects of foreign manipulation of the region’s religious and ethnic diversity. Self-criticism, in short, does not preclude being anti-colonial, or recognizing the dangers of both domestic and foreign threats to national sovereignty.

Indeed, the Western idea of a “sectarian” Middle East has been inextricably bound with modern Western domination over the region; the idea of an innate Middle Eastern or Islamic sectarianism serves to absolve Western powers from their complicity in creating, encouraging, or exacerbating divisive political landscapes. A recent manifestation of this obfuscation and such ideological deployment of the idea of the sectarian Middle East occurred in 2003, when L. Paul Bremer II, the US administrator of the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq who spoke no Arabic and, by his own admission, knew very little about the country—rationalized the sectarian effects of US interventionism by insisting that Iraqis only “vaguely understand the concept of freedom,” and pleaded for US guidance. In his view, sectarianism in the region was endemic, so much so that Bremer described parts of Iraq as “the Sunni homeland.”

Indeed, the Western idea of a “sectarian” Middle East has been inextricably bound with modern Western domination over the region; the idea of an innate Middle Eastern or Islamic sectarianism serves to absolve Western powers from their complicity in creating, encouraging, or exacerbating divisive political landscapes.

This description reduces Iraqis to a single sectarian affiliation as if it were primordial and as if it trumped kinship, history, geography, national affiliation, ideology and so on. It is the equivalent of granting a non-American enormous power to reshape the United States and having him describe the area between Boston and New York as the “white homeland,” other parts of the United States as the “Latino homeland,” and still other parts as the “African-American homeland,” with all the violence that such grotesquely reductive descriptions entail. The aftermath of the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, of course, witnessed not only the destruction of what remained of the secular Baathist Iraqi central state; it also created a new Iraqi Governing Council along explicitly sectarian lines. This fateful decision to divide Iraqi government along “Sunni,” “Shiite,” and “Kurd,” or to invent a “Sunni triangle,” was not predetermined objectively by the diversity of Iraqi society. It was principally a US imperial interpretation of this diversity.

More blatantly, then-Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice confidently declared, in 2006, amidst Israel’s devastating US-backed assault on Lebanon, that the world was observing the “birth pangs of a New Middle East.” This, too, displayed how Western interventionism and imperialism in the region not only exacerbates “internal” problems, but also creates new conditions and contexts that define the very nature of what is internal.

In 2016, President Barack Obama said of the Middle East, “[Its] only organizing principles are sectarian,” and that the conflicts raging there under America’s watch “date back millennia.” But Obama’s assertions were both deeply injurious and self-serving. Injurious because they discount the rich, twentieth-century history of the Arab world that underscores the numerous social and political bonds in the region which are manifestly not sectarian; self-serving because they affirm an imperial self-righteousness that presumes that the problems of the Arab world, including those that affect the United States, are due to the persistence of immutable sectarian solidarities. This assertion casts the problem of sectarianism as principally and essentially an Arab one. We have tried to help them, the message goes, but they are hopeless.

Of course, it would be absurd to insist that there are not local and regional actors who play the complex modern sectarian game along with Western powers. It would be absurd, as well, to deny that religion and religious differences are not salient features in the history of the Middle East as they are in many other parts of the world as well. For centuries, the Ottoman Empire used religious categories to classify and discriminate against its vast and diverse subject population. The so-called millet system established ecclesiastical and communal autonomy for Greek Orthodox, Armenian, and Jewish subjects in the empire. Islamic law unquestionably distinguished and discriminated between Muslim and non-Muslim. The ruling Ottoman dynasty and its elites proclaimed themselves repeatedly to be defenders of Islam, locked in a struggle against heretics and infidels.

One can, therefore, discuss sectarian outlooks, actions, and thoughts in the Middle East in a manner similar to how one would talk about racial (and racist) outlooks, actions, and thoughts in the United States. Yet just as American scholars have gone to great lengths to challenge the notion of singular, age-old racial identifications, whether black or white, so too should scholars of the Middle East reject the facile, monolithic, and ahistorical interpretations of sectarian identity so beloved by academics, pundits, think tank “experts,” and politicians.

Sectarianism is far less an objective description of “real” fractures in a religiously diverse world and far more a language about the nature of religious difference in the Middle East. It is a discourse that has been deployed and expressed by both Middle Eastern and Western nations, communities, and individuals to create and justify political and ideological frameworks in the modern Middle East within which supposedly innate sectarian problems are contained, if not necessarily overcome.

In this way, the “sectarian” Middle East does not simply exist; it is imagined to exist, and then it is produced. Yet the strong association of the term “sectarianism” with the Middle East repeatedly suggests that the region is more negatively religious than the “secular” West. This is an ideological assumption woven into how the Arab and Muslim worlds are generally depicted as having fundamentally religious landscapes. Not only does this assumption gloss over how religious the West actually is, it also pretends that what is occurring in the Middle East reflects an unbroken arc of sectarian sentiment that connects the medieval to the modern. Modern politics, in short, is transformed into little more than a reenactment of a medieval drama between Sunni and Shi‘i, rather than being a geopolitical struggle in which Western states are deeply implicated.

I am for this reason in sympathy with Syrian historian Aziz al-Azmeh’s criticism of the “over-Islamization of Islam.” This fixation with the study of Islam, the Muslim, the Muslim woman, and Islamic piety has ignored and relegated as historiographically and analytically unimportant secular Arabs, or Muslim Arabs who do not necessarily flaunt their piety in ways that conform to Western stereotypes. It also effaces the agency and histories of non-Muslim Arabs, Turks, Iranians, Armenians, and others who have lived, interacted with, and shared a culture with Muslims across the Middle East. Most of all, this Western fixation with the allegedly medieval and fixed nature of religiosity in the Middle East distracts scholars and the general public from understanding the modern roots of the “sectarian” Middle East.

This fixation with the study of Islam, the Muslim, the Muslim woman, and Islamic piety has ignored and relegated as historiographically and analytically unimportant secular Arabs, or Muslim Arabs who do not necessarily flaunt their piety in ways that conform to Western stereotypes.

I am not suggesting that we think of sectarianism as only, or even primarily, a question of colonial “divide and rule.” But I am saying that we should stop pretending that the so-called internal dimensions have not themselves been massively affected, exacerbated, and even transformed by the West. When the noted political scientist Fouad Ajami tendentiously insisted that the “self-inflicted” wounds “matter” more than foreign ones, he obfuscated the degree to which the foreign has long shaped the landscape in which the “local” plays itself out. Rather than assume sectarianism to be a fixed, stable reality that floats above history, it is far more important to locate and identify—to historicize—each “sectarian” event, moment, structure, identification, and discourse in its particular context.

What is needed urgently, therefore, is a new research agenda to study the dialectic—the complex, constant, and unequal relationship between local and foreign—that makes up the modern Middle East. We also need to appreciate the dynamic between tradition and transformation, between history and politics, between self-identification and orientalist representation, and between discourse and action that makes up the substance of what we call “sectarianism.”

This essay is derived from a February 2017 article published by the Center for the Middle East at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

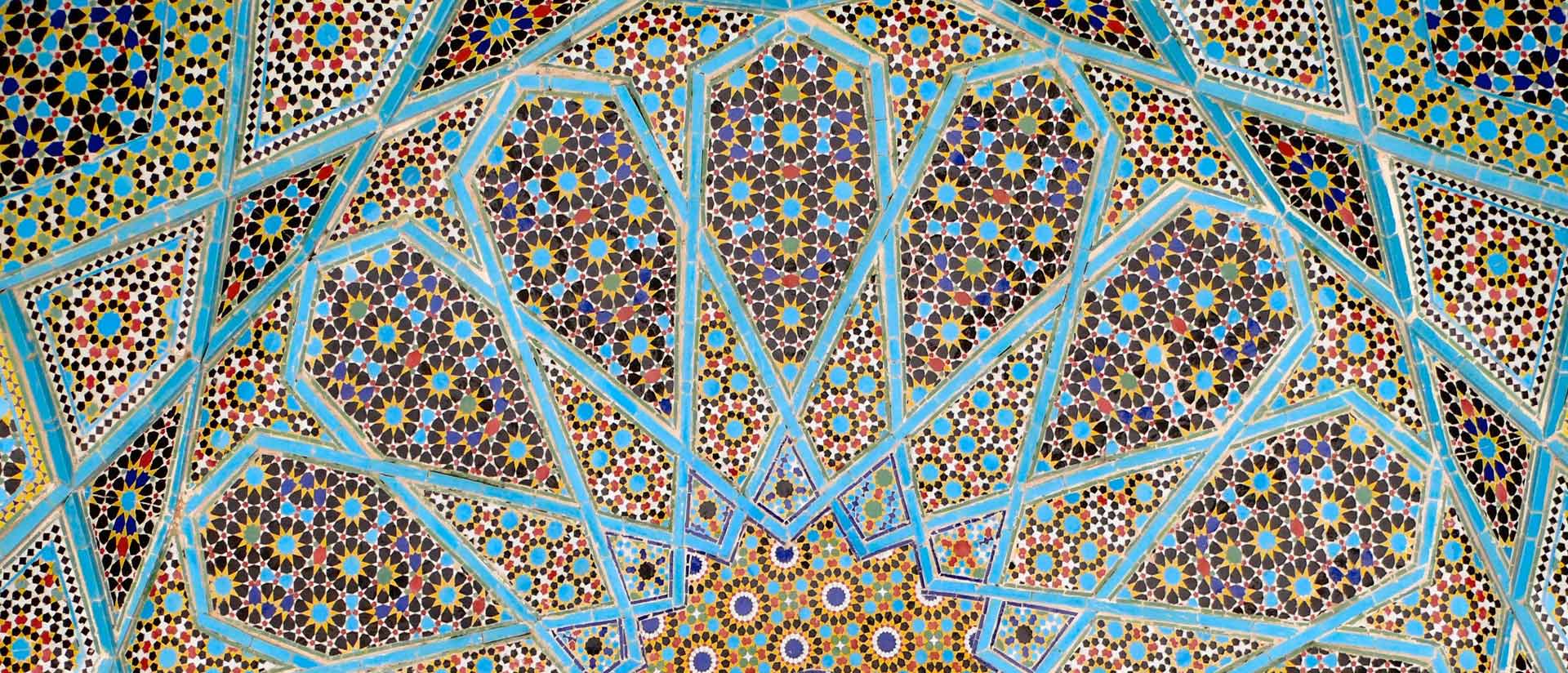

Photo: Iranian glazed-ceramic tiles, ceiling of the Tomb of Hafez, Shiraz, Iran. Source: Pentocelo, Wikimedia.