This Land Is Your Land

Legislating dispossession in colonial West Africa

By Mariana P. Candido

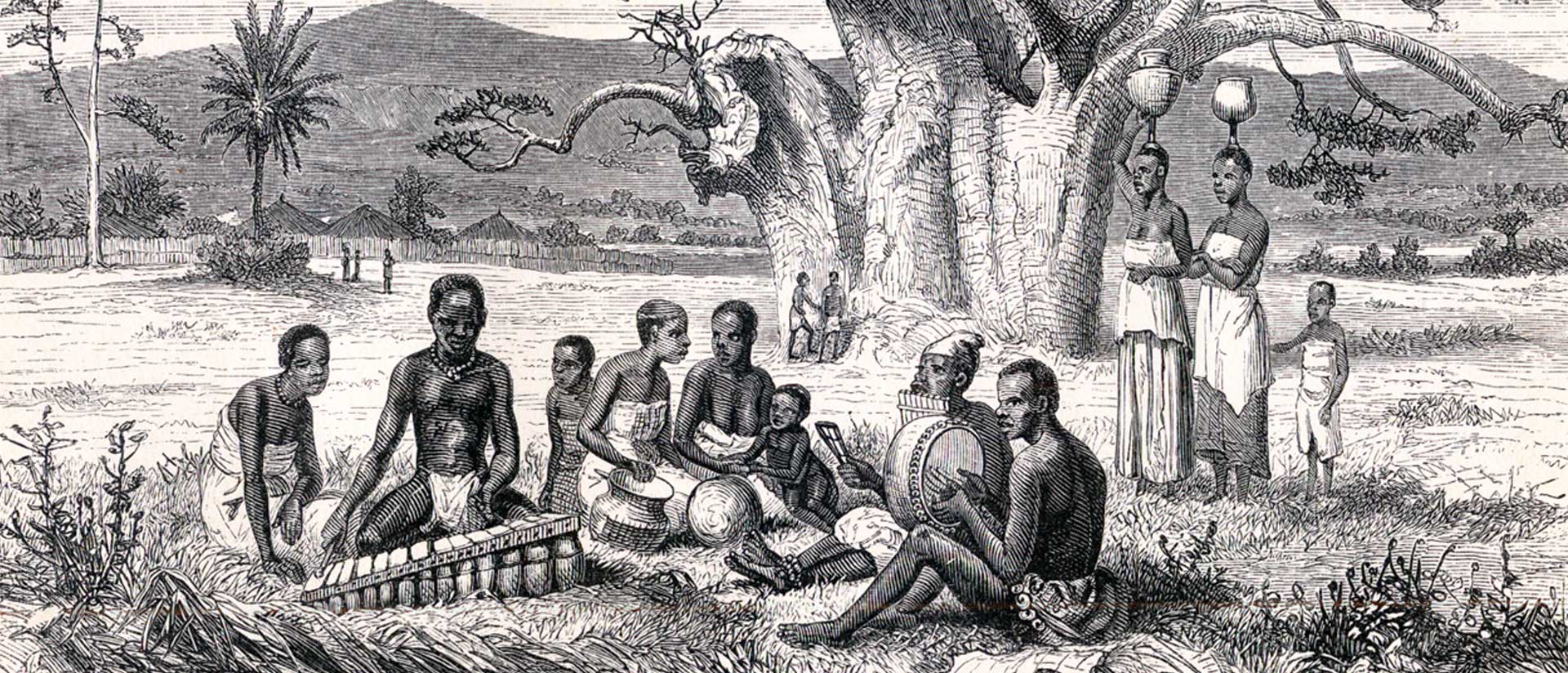

IN RECENT DECADES, several studies have stressed the cultural and social importance of land for populations in West Africa. Land value went beyond its materiality and defined rights, obligations that linked rulers and their subjects. In sum, land was central to the political economy that sustained relationships and sovereignty. The same is true for populations in West Central Africa, including Mbundu, Umbundu, and Kwanyama and other non-Bantu populations that understood land not simply as a space of food production but also a space of belonging and maintaining contact with previous generations. Occupation of territory, and its use, defined rights over access and use, including over rivers and small lagoons. These ideas, however, were challenged by the arrival of European powers during the modern era, who expropriated land and justified it.

Possession of territory and control of its inhabitants and natural resources were the ultimate goals of expansionist Iberian powers. Since the fifteenth century, Portuguese and Spanish monarchies aimed to exercise control of newly encountered territories, debating whether indigenous populations did or did not have a right to land and jurisdiction over territories and peoples. Before the nineteenth century in Portugal, or in most of Europe, however, there was no such a thing as a consolidated idea that land belonged to individuals and fixed law that legislated over it. By the 1800s, when the Portuguese state became interested in legislating property laws in Angola, it was in the context of ongoing European debate regarding land enclosure, communal use of land, and unproductive land influenced by Enlightenment and liberal ideas regarding progress, modernity, and productivity. By the second decade of the nineteenth century, however, the state began to encroach on communal land in Portugal, seen as an obstacle to the progress of capitalist agricultural practices that privileged private investment at the expense of collective gains.

In this perspective of liberal progress, communal land where people grazed sheep or cattle or collected water was understood as a sign of Portuguese economic shortfall; to achieve prosperity, the state had to distribute community land to individuals who would make their plots productive, addressing the market demands for specific crops. The debate over property rights in Portugal was directly linked to the existence of overseas colonies and the need to justify its occupation. In Angola, legislating ownership normalized possession and occupation of the territory, but also the status of its inhabitants as colonial subjects with limited rights. Legislation implemented in nineteenth-century Angola to protect individual property rights over things, land, and people reflected and consolidated governance and legitimacy. Notably, those laws made use of a language and a technology, based on the dominance of a paper culture, that determined colonized populations as being outside of history, lacking the cultural practice and economic sophistication to rule themselves. The consolidation of legislation and colonial courts made expropriation easier and normalized conquest, occupation, and inequality.

In Angola, legislating ownership normalized possession and occupation of the territory, but also the status of its inhabitants as colonial subjects with limited rights.

West Central African populations understandably also valued land and pushed back attempts of colonial officers to seize territory in different ways, most not necessarily effective from a long-term perspective. Rulers and commoners embraced techniques, such as written records, that allowed them to have their occupation rights recognized by others since the seventeenth century. In few instances, however, historians have access to these records – and this is the case of the surviving records of the Caculo Cacahenda’s archives, which documented lineage history and migration, land tenure, and territorial limits since 1677. These documents became regalia of power in part because they described political and economic events, but, more importantly, control over these written papers legitimized political rule, the state, and its relationship with the colonial administration. The existence of local state archives, such as the Caculo Cacahenda, as well as Umbundu records, indicates how the West Central African population embraced written technology to produce the evidence that could serve as proof for their land tenure claims. Missing from these records, however, are gendered dynamics of land claims and use, which are prevalent in colonial historical documents.

West Central African rulers appropriated written records when they realized that paper evidence, not possession and occupation, achieved the role of land tenure proof. This change was linked to the advance of Enlightenment thought, new forms of governance, and the ensuing discourse of modernity and civilization at the turn of the nineteenth century. It led to the imposition of a new technique – writing – and to bureaucracy, altering everyday practices and governability. Manufactured evidence was privileged, in most cases, by omitting local populations’ claims that supported counter-narratives of ancestral rights. Writing was also linked to legislation, rights, and ownership, legitimizing one form of power over others and displacing multiple legal orders in favor of a single narrative that privileged the colonial experience as central. Written evidence and property law were crucial in philosophical and political narratives of development that privileged individual rights as modernity in opposition to West Central Africans who supposedly lacked regulations, written culture, and private ownership laws.

Writing was also linked to legislation, rights, and ownership, legitimizing one form of power over others and displacing multiple legal orders in favor of a single narrative that privileged the colonial experience as central.

This argument can be easily dismissed by the existence of the Caculo Cacahenda archive, seized by a colonial officer in 1934, as well as the survival of other records. This was all part of an imperial discourse that denied rights despite clear evidence that West Central African societies had multiple jurisdictions, recognized possession and occupation rights, and registered them. African rulers and commoners produced evidence that legitimized their ownership claims, but Europeans looted their symbols of power, including seats, divination baskets, and written documents carefully manufactured and held.

By the mid-nineteenth century, titling processes and the designation of land for individual and communal use radically transformed the use and access to land in West Central Africa. In many ways, the recognition of private ownership of land in nineteenth-century Angola was a mode of dispossession that continued in the twentieth century and later. It legitimized the capacity of an individual, including a foreigner, to usurp, appropriate, and claim ownership over locals who lived and depended on land resources. The colonial state that ruled on ownership of land and things recognized inequality. As such, the consolidation of individual property rights played a significant role in the narrative of progress and modernity employed by colonial administrators and jurists in Portugal and Angola. During the nineteenth century, rights shifted from the earlier use of occupation of sobas (local rulers) and their subjects toward a more abstract form of individual property rights based on registration, titles, and written evidence that privileged colonial governance. Many African subjects, particularly women, were able to navigate and employ colonial law to advance their economic interests and agendas. This does not mean that their ability to employ legal spaces was successful or unchallenged by their peers.

Jurists and colonial officers misunderstood and mis-presented West Central African land regimes, privileging private over collective holdings, and setting in stone, or on paper, norms and practices that were undergoing reformulations. The support of chiefs who facilitated the colonial agenda favored the consolidation of specific voices and versions of the past, and practices that excluded youths, women, and anyone seen as dissident or nonconformist. The rush to register customary law and jurisdictions reinforced Western perspectives and notions of property, in the context of the expansion of colonialism and territorialization. Thus, it is not surprising that the little information on customary law recorded in early twentieth-century Angola stresses the absence of private ownership and women’s exclusion. Written culture and legal forms of individual ownership and knowledge production in indigenous societies were articulated and realized in conjunction with one another, consolidating dispossession, colonialism, and inequalities.

FOR MORE THAN five centuries, West Central African societies were connected to distant markets abroad and inland. After the 1600s, they influenced how European empires conceived of and regulated ownership, as well as how they engaged in struggles over possession, control, and rights. The social lives of societies and objects tell us why and how people accumulated things over time and the ways in which they expressed rights and wealth. At a time of economic transformation, new notions of rights emerged, and written forms of claiming ownership were consolidated. Historical documents available in Angolan, Portuguese, and Brazilian archives shed further light on this economic transformation, which was associated with the Portuguese conquest and occupation, the expansion of the transatlantic slave trade, the implementation of a plantation economy, and the land rush along the West Central African Coast from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century.

For more than five centuries, West Central African societies were connected to distant markets abroad and inland. After the 1600s, they influenced how European empires conceived of and regulated ownership, as well as how they engaged in struggles over possession, control, and rights.

Indeed, evidence from Angolan archives reveals that West Central Africans owned land, material objects, and people before the twentieth century. Still, most of the studies published in the past fifty years recognize only their ownership of dependents, as if the lands they occupied were devoid of legitimate occupants creating historical narratives that normalize displacement, removal, and violence. The social inequalities of the last century in Angola relate to the past and are legacies of imposition of individual property rights over collective ones at a specific historical moment, the mid-nineteenth century. Liberal principles of land use, productivity, and ownership are also normalized in narratives that take for granted that European rights have always recognized individual property while multiple jurisdictions in West Central Africa did not, without interrogating the historicization of these processes. To obtain to a clearer view, it is vital that historians of Africa pay particular attention to the nature of the archives that normalize conquest, occupation, and exclusion—and which ultimately obscure West Central African forms of knowledge, ownership, and legitimacy.

This essay appears in the 2023-24 Berlin Journal (#37) and is excerpted and adapted from the Introduction of Mariana P. Candido’s book Wealth, Land, and Property in Angola: A History of Dispossession, Slavery, and Inequality (Cambridge University Press, 2022). Reproduced with permission of the Licensor through PLSClear.

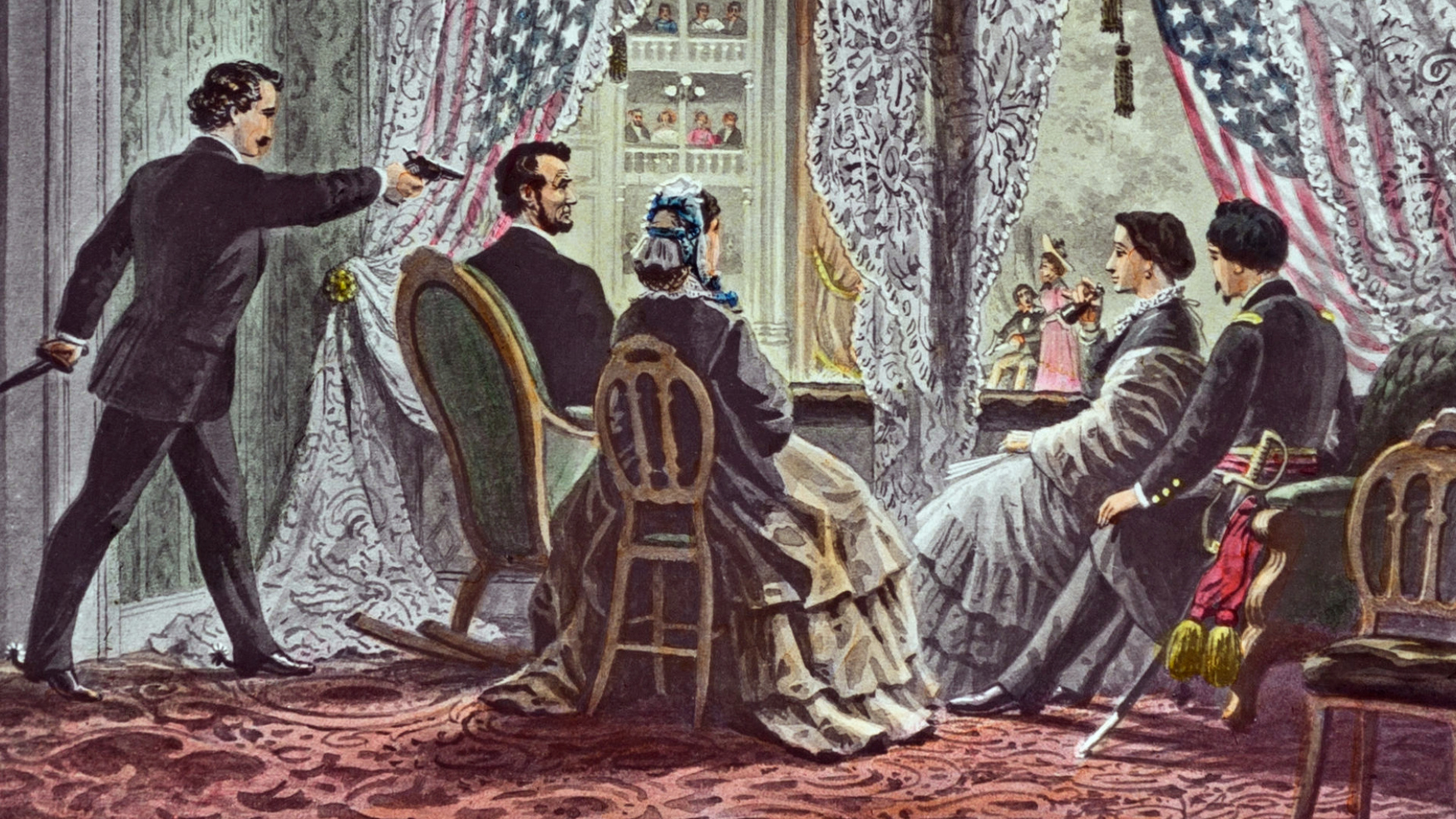

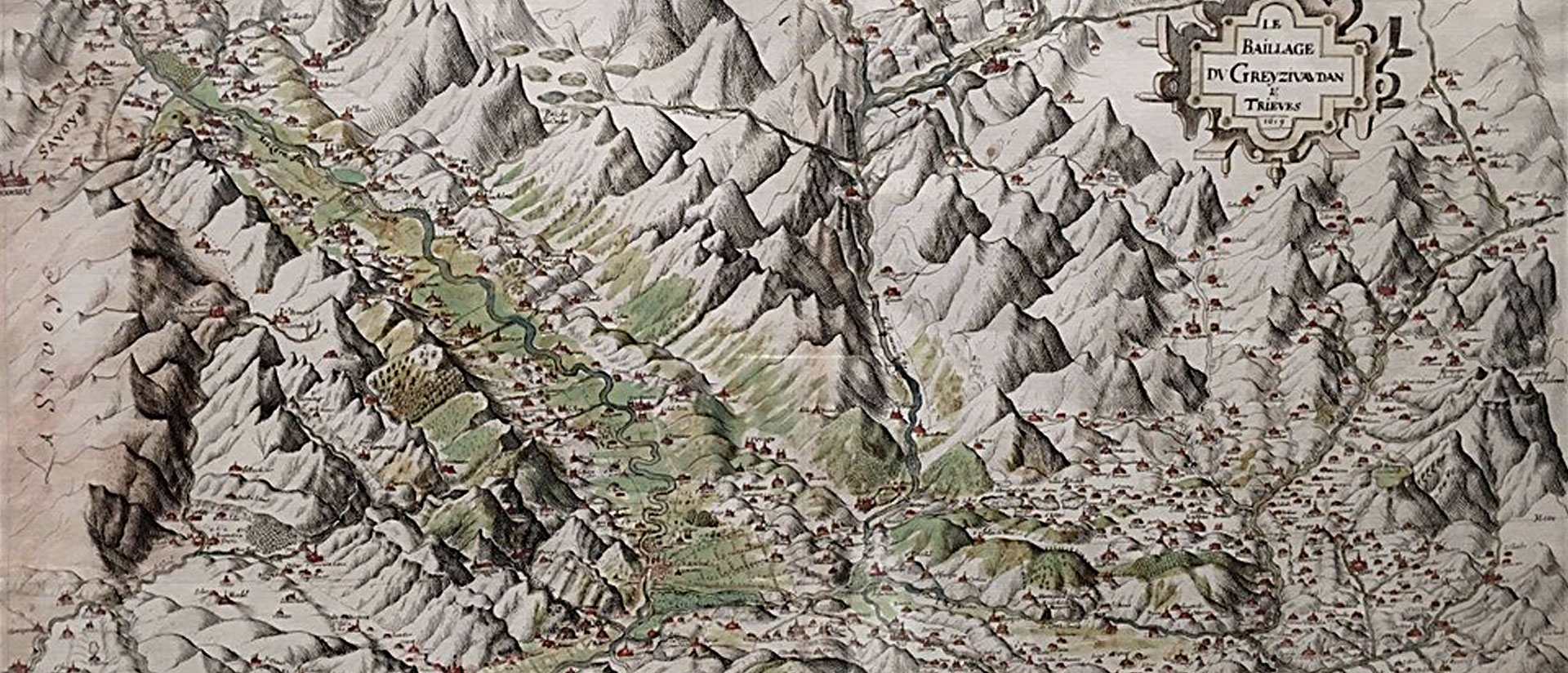

Image: Dirk Jansz van Santen, Regna Congo et Angola (detail), copper-engraving print, 45 × 54 cm, from Joan Blaeu’s Atlas Maior (1662). Courtesy Koninklijke Bibliothek, Amsterdam