The Tide Was Always High

Listening to Los Angeles

By Josh Kun

Music and musicians from Latin America are inextricable from the development of Los Angeles as a modern musical city. The musical life of this dispersed and dynamic metropolis has been and continues to be shaped by immigrant musicians and migrating, cross-border musical cultures. They have not only helped determine the sonic landscape of the city’s musical urbanism; they have also been active participants in the making of the city’s modern aesthetics and modern industries.

The music of Los Angeles and the music of Latin America have been interwined since the very birth of the city, in the eighteenth century. As the American ethnomusicologist Sidney Robertson Cowell reminded, back in the 1930s, there was, in fact, no Anglo-Saxon music in Los Angeles until the mid-nineteenth century; before then, “Americans were numerically few and transient.” The original music of Los Angeles belonged instead to Gabrielino Indians, Mexican vaqueros, and Spanish friars and mission bands long before it began sounding like anything else. “Twenty years after the discovery of gold,” the mid-century journalist Carey McWilliams wrote, “Los Angeles was still a small Mexican town.”

The original music of Los Angeles belonged instead to Gabrielino Indians, Mexican vaqueros, and Spanish friars and mission bands long before it began sounding like anything else. “Twenty years after the discovery of gold,” the mid-century journalist Carey McWilliams wrote, “Los Angeles was still a small Mexican town.”

For all of the demographic and cultural shifts that were to come over the next hundred years, to make music in Los Angeles—whether it be surf rock, bebop, gangsta rap, or cosmic canyon folk—has always borne an echo of that small Mexican town and has always meant, to some degree, engaging with the sonic traditions and experiments of Latin American music and the musical histories of immigrant Latin American musicians. This is both by virtue of its location and history (Mayor Eric Garcetti likes to call LA “the Northernmost city of Latin America”) and by virtue of its multi-immigrant populations (a city that has always been a key hub for immigrants from across Latin America).

There is no music of Los Angeles without mariachi and banda and son jarocho, without bossa nova and samba, without mambo and cha cha cha and salsa, without Latin jazz helping West Coast jazz and its sound, without R & B and rock tuning “south of the border” or “South American Way.” How could we listen to LA (Los Angeles) without the music of LA (Latin America)? How could we listen to Latin America without the music of Los Angeles? The city’s distinctive musical urbanism is unthinkable without Latin American migrant sounds and migrant musicians. “Boom in Latin rhythms bigger than ever in LA,” the jazz magazine Down Beat declared in 1954, but the truth is that the boom was always booming, the tide was always high.

Los Angeles, we might say, has a Latin American cadence. Inspired by Ralph Ellison’s now famous aside in Time magazine that America is “jazz-shaped,” Robert G. O’Meally, the celebrated founder of Columbia University’s Center for Jazz Studies, has convincingly written that there is a “jazz cadence” embedded within the experiences of twentieth-century American culture—a jazz “effect” or jazz “factor” that has informed speech, style, dance, poetry, film, and politics to such a degree that jazz emerges as “the master trope century—the mariachi cadence of American culture, the mambo cadence, the samba cadence—but within the history of Los Angeles, the Latin American cadence is hard to ignore: among the city’s most consistent beats, its most influential set of rhythms and melodies are those that have arrived after traveling through a century or two of cultural contact and musical creativity in the Americas.

Within the history of Los Angeles, the Latin American cadence is hard to ignore: among the city’s most consistent beats, its most influential set of rhythms and melodies are those that have arrived after traveling through a century or two of cultural contact and musical creativity in the Americas.

In John Fante’s classic Los Angeles novel Ask the Dust, published in 1939, the Italian immigrant protagonist Arturo Bandini struggles to survive LA and its one song that never leaves him alone: “Over the Waves.” Played repeatedly in the novel by a small group of musicians at the downtown Columbia Buffet restaurant, it scores his embattled relationship with the waitress Camilla—a “Mayan Princess”—and, by extension, his embattled relationship with the Mexican roots of the city. It’s the soundtrack to his awakening to Latin American Los Angeles and to his own position as a down-and-out writer living on oranges in his Bunker Hill apartment. The only other hint of music in the novel is also tinged with Latin America: a Central Avenue nightclub called Club Cuba.

“Over the Waves” began its life as “Sobre Las Olas,” a European-style waltz written in Mexico by the composer and violinist Juventino Rosas. As scholars Gaye T. Johnson and Raul A. Fernandez have documented, Rosas took the song to New Orleans for the 1884 New Orleans World Cotton Centennial Exposition sugar expo and both he and the song stayed on, introducing the latter’s cross-border, cross-continental swells to both the classical and jazz repertoires of early-twentieth-century New Orleans. As “Over the Waves,” it became a staple for the city’s working musicians, and most likely found its way to Los Angeles as New Orleans and other Southern musicians—such as Jelly Roll Morton (who went on to play in Tijuana, Mexico) and Leon Rene (who wrote “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South” beneath the palm trees)—began to migrate west in the 1920s and 1930s.

By the time Bandini couldn’t escape it, “Over the Waves” was a migrant song that had become an LA staple, music from Latin America that had traveled over borders and represented, however covertly, the histories of all those who traveled over the waves to make Los Angeles their home. Even though Fante didn’t point it out, “Over the Waves” was a musical prompt to ask the dust, to ask history for answers, to listen to what decades later the Chicano-led band Rage against the Machine would call the Battle of Los Angeles: the music of empires clashing.

No wonder that of the few city statues in Los Angeles dedicated to musicians, three are from Mexico: revered composer and singer Agustín Lara and ranchera idols Lucha Reyes and Antonio Aguilar. While Lara’s statue hearkens back to the 1930s and 1940s, when he was beloved by Mexican and Mexican American audiences in Los Angeles, the statues of Aguilar and Reyes are in direct dialogue with the contemporary moment. The working-class and immigrant-conscious genres that they helped popularize in their songs and feature films—ranchera, banda, norteño—among the most popular and most commercially successful in twenty-first-century Los Angeles among both immigrant communities and Latina/os born and raised here.

That the city’s rock, pop, jazz, funk, and hip-hop cultures all can trace some roots to Latin America is an open secret among musicians and fans, but one that has been little documented by scholars and journalists.

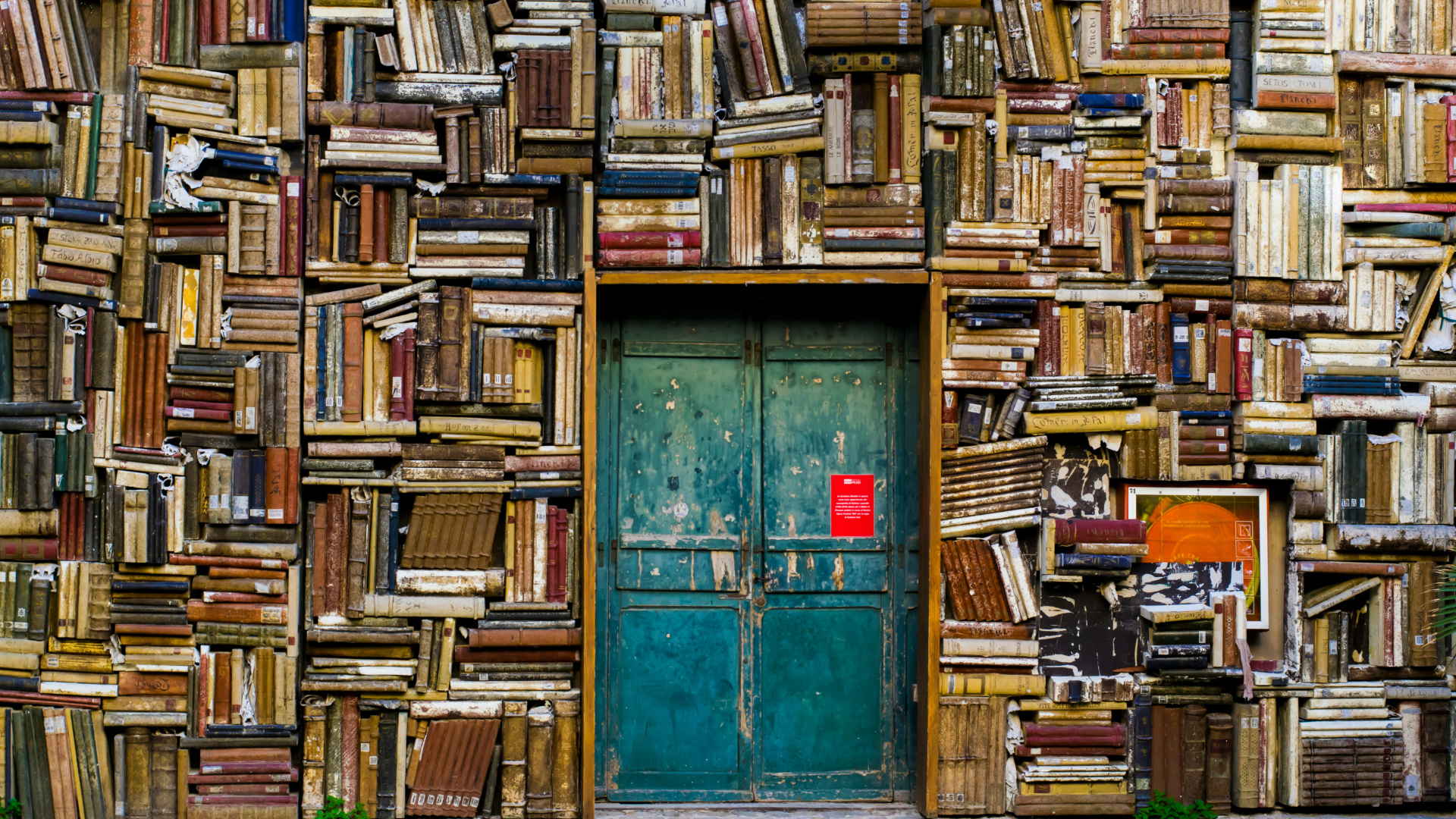

Beyond Mexican Los Angeles, though, the wider story of the musical interconnection between Latin America and Los Angeles has been less robustly told. That the city’s rock, pop, jazz, funk, and hip-hop cultures all can trace some roots to Latin America is an open secret among musicians and fans, but one that has been little documented by scholars and journalists. Much of that other history lives in the liner note essays of LPs, in band personnel credits and musicians’ union session archives, in the oral histories and memoirs of label execs and musicians, and in the small print of Billboard magazine calendar blurbs, nightclub ads, and micro concert-reviews. What they collectively reveal is that so much of the music we have come to know as belonging to Los Angeles, as being of Los Angeles—be it Ritchie Valens work-shopping “La Bamba” in a Silver Lake home studio (belonging to Del-Fi Records’ Bob Keane) or Lalo Schifrin putting bongos at the foundation of the Mission: Impossible theme, or even the Beach Boys wearing huarache sandals—has come over the waves and over the borders of the Americas.

This essay is adapted from the Introduction to The Tide Was Always High: The Music of Latin America in Los Angeles (University of California Press, 2017), edited by spring 2018 fellow Josh Kun. A collection of essays, interviews, photographs, and album covers, the volume is a companion to six public concerts that Kun has curated across Los Angeles, as well as a series of online playlists, as part of the Getty Foundation initiative Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA. For more information, visit tidewasalwayshigh.com

Photo: Vlanka, Calaveritas, 2015. Courtesy of Creative Commons

Register for Josh Kun’s Academy talk on March 20, 2018, at 7:30 pm CET: “Sounds of Detention, Sounds of Escape: Listening to the Migrant Songbook”