Playing Guqin

Learning the instrument of philosophers and sages

By Carolyn Chen

The guqin is seven-string Chinese zither. Its body is a single piece of wood, hollowed to resonate, with seven strings strung over the top. Most guqin repertoire is solo. It is a quiet instrument. In folklore, it is played on a mountaintop in the middle of the night, to bring the player into harmony with the self and with nature. The decade-plus that I have studied guqin has been a long meditation on this idea of music as a way to seek for a harmonious relationship with our environment.

I first met the guqin by accident. Growing up in New Jersey, I never really encountered opportunities for learning a Chinese instrument. Had I been offered a choice, I might have gravitated toward the conversational-sounding two-string fiddle, the erhu, or the mellow gourd-mounted free-reed pipe, the hulusi. In my last year at university, the music department at Stanford started offering classes in guzheng, the larger, more extroverted and brilliant-sounding relative of the guqin. Then, in my first year of graduate school, I had the fortune of being assigned to assistant-teach for Music of Asia at the University of California, San Diego. One of the first guest lecturers was the neurocomputational ethnomusicologist Alex Khalil, then a graduate student, who had first ventured to China to research stone bells, discovered the guqin, and then returned many times to deepen his study of the instrument. Alex was starting a guqin club as an elective course, and I enrolled. He led us in building practice instruments from wooden planks and guitar pegs, and taught us to decipher the instrument’s unique notation system, play through beginning repertoire, and come to appreciate the particularly rich body of myth and folklore surrounding the instrument.

The guqin is also a zither like the guzheng, but its notation and technique are far more intricate. On a guzheng, each string mostly makes one note, sometimes ornamented with vibrato or sliding. Traditional guqin tablature notation delineates exactly which finger plucks each note, as well as the direction it moves. Left hand techniques are many. Not only is each depressed note assigned a particular finger placed at a given tenth of a division from a numbered harmonic node, but notation also often specifies the quality of approach to or departure from a note, with myriad varieties of glissandi and vibrato. The density of information embedded in the 1,500-year-old notation system makes it difficult to sight-read. Notation usually serves more as a memory aid, or a supplement to oral tradition. Most music is transmitted from teacher to student seated across one another, memorizing one phrase at a time.

The density of information embedded in the 1,500-year-old notation system makes it difficult to sight-read.

The guqin was not built for auditoriums or grand halls, but traditionally played in a small yaji, an “elegant gathering” of a few players or like-minded listeners. A beginning guzheng player can immediately produce a brilliant sound with tortoise-shell finger picks. An aspiring guqin player must practice to find the right combination of finger and nail to produce a sound with body and clear onset. The guqin is something of an expert at disappearing. Traditional silk strings never ring as brightly as modern steel and nylon. The sound retires. There is something private about how it hovers transparently for a moment and evaporates like a trace of perfume or the blink of a firefly.

In part because of its quietness, the guqin has strong associations with a particular intimacy in listening. Frequently in traditional repertoire, a note plucked from a soft silk string will stop ringing before the hand has finished moving through the phrase. In this silence, the music continues in the mind of the educated listener, leaping from physical vibration into the resonance of the imagination. The guqin requires an attentive listener with a still mind – at one moment to witness the brief instant of the sound’s bloom, and then to hold the flavor of its lingering memory.

In one legend, Boya, the famous master player, meets the woodcutter Zhong Ziqi, his ideal listener, who, despite a lack of formal education, quasi-telepathically infers the player’s every mental image through listening. When Boya plays thinking of high mountains, the woodcutter thinks of high mountains. When he thinks of flowing waters, so does the woodcutter. When the woodcutter dies, Boya breaks his instrument and never plays again. Thus the term 知音 (zhiyin, “to know the tone”) describes a best friend or soul mate.

This storied listening has an undeniable appeal. It’s the dream of being totally understood, of being completely connected to another mind in a way that transcends language. In some ways, it recalls the fantasy of music as a universal language, except that in this version, the connection is a singular phenomenon. Boya never plays again, because after such an experience of oneness, anything else could only disappoint.

Could I aspire to this? I wouldn’t know where to look for a woodcutter. In the genre of music-making that I have trained in, new music, this story might more likely start from an instrument broken before anyone might overhear it, confirming the negative possibility of understanding. The idea of a listener in complete unison with the musician’s thoughts might seem anathema to a genre valuing a multiplicity of interpretations. The situation in my experience that might come closest to the communion of Boya and the woodcutter would be the kind of improvisation where everyone is listening closely enough to leave space for one another’s intentions – where you can hear the quietest person in the room.

The guqin has a long history as a symbol of Chinese high culture. In Imperial China, guqin was one of the four arts of the scholar class, along with calligraphy, painting, and go. It is considered an instrument of philosophers and sages. Practicing the instrument can be seen as a kind of self-cultivation, with the Confucian aim of nurturing one’s mind, and the Taoist aim of seeking harmony with nature. Playing is said to calm the heart, center the mind, and nurture the character through meditation. The recent revival of interest in guqin might be due to its symbolism as a refuge from the speed and stress of contemporary life.

The recent revival of interest in guqin might be due to its symbolism as a refuge from the speed and stress of contemporary life.

When I was studying guqin in Hangzhou, I joined a tai chi group practicing in front of the West Lake every morning. An artist friend asked my why my interests were all so geriatric. She found the slowness and stillness of both tai chi and guqin music elegant and excruciating. She said she aspired to learn the arts in her twilight years, and not sooner.

Traditional Chinese paintings including the guqin show mostly solitary players in natural landscapes, surrounded by craggy mountains, gnarled pines, and mist. They might call to mind Caspar David Friedrich’s iconic Wanderer above the Sea of Fog with the solitary figure looking out over a rugged mountain landscape. Friedrich’s Romantic explorer of wind-tousled hair and bent knee looks somewhat more athletic and exultant, though, than the guqin sages, who are more faintly delineated and in humbler proportion to the landscape. Oftentimes the eye might need to wander the mountains for a while before setting sight on a tiny figure with a long instrument.

In 2016, I went to Beijing with electronic musician Amble Skuse on a project developing music for electronically-enabled guqin performing in environments urban and natural: outside a metro stop in Beijing, on the outdoor steps of a commercial amphitheater, over a water reservoir, and climbing to a deserted section of the Great Wall outside the city. Actually sitting outside trying to play guqin was not as harmonious as the paintings suggested. When we set up to play we did hear the chirping of birds, the sighing wind, or the rush of traffic. But each new location also required negotiating a way to sit on uneven ground balancing the guqin without muting it, and carrying the instrument around without whacking it into foliage or injuring it with dampness or heat. In the mountains atop the Great Wall at Gubeikou at dusk, our meditation included ignoring the mosquitos hovering over their fresh buffet, and creating a suitable recording before sunset obscured both camera function and the path back to civilization. But then again these are all essential elements of the environment that we were encountering. Why wouldn’t an experience of nature include both inspiration and obstruction?

In the city, passersby sometimes paused, but more often walked past our performance. We were like invisible buskers, too quiet to compete with the environment. Guqin tradition stipulates that the instrument should only be played for a worthy person. Amongst the picturesque prohibitions catalogued in Robert van Gulik’s classic Lore of the Lute: one should not play guqin when sweaty; when having recently eaten, drunk, had sex; when in a court room or near a prison; or for a merchant, barbarian, or vulgar person. The idiom 對牛彈琴, playing qin to a cow, describes the wasted effort of talking to someone who cannot understand. But the drifting attention and disinterest of passersby – or even the chatter of people sitting next to us, talking over our playing – deepened the performance in other ways. To be gently ignored, or dismissed from the center of attention, releases music-making from the pressure of proving competence, or of crafting a master-trajectory of audience interest. The persisting continuity of these other everyday tasks and intentions brought the music closer to the status of wind-blown leaves and rushing water. After all, nature is what does not ask to be listened to.

To be gently ignored, or dismissed from the center of attention, releases music-making from the pressure of proving competence, or of crafting a master-trajectory of audience interest.

In some ways, playing guqin has made me notice the ways in which practicing anything can become a kind of self-cultivation. I once asked my mother why she put me in piano lessons as a child. She remembered Yamaha ads in Taiwan with a slogan that children who play piano won’t be bad. She had the somewhat Confucian idea that learning piano would make me a good person, or at least an obedient child. I took a piano lesson roughly every week for almost two decades. Regardless of the musical results, the sheer quantity of time I spent sitting at the keyboard did shape my personality. Practicing piano taught me to sit still, to be solitary, to make peace with the act of practicing – breaking down difficult things into smaller physical actions reenacted over and over until the thinking and resistance was washed out of them. The Western ideal of a virtuoso refers to a performer of extraordinary technical ability – but also submits the virtue of erasing the self through physical feats. This ironing out the ego might align with the Taoist ideal of taking refuge from the ills of society and human politics by retreating into nature, perhaps with a musical instrument. In some ways, sitting at a living room piano might be its own kind of midnight mountaintop meditation.

This essay was first published in The Middle Matter: Sound As Interstice, eds. Caroline Profanter, Henry Anderson, and Julia Eckhardt (Brussels, umland, 2019), pp. 47-52.

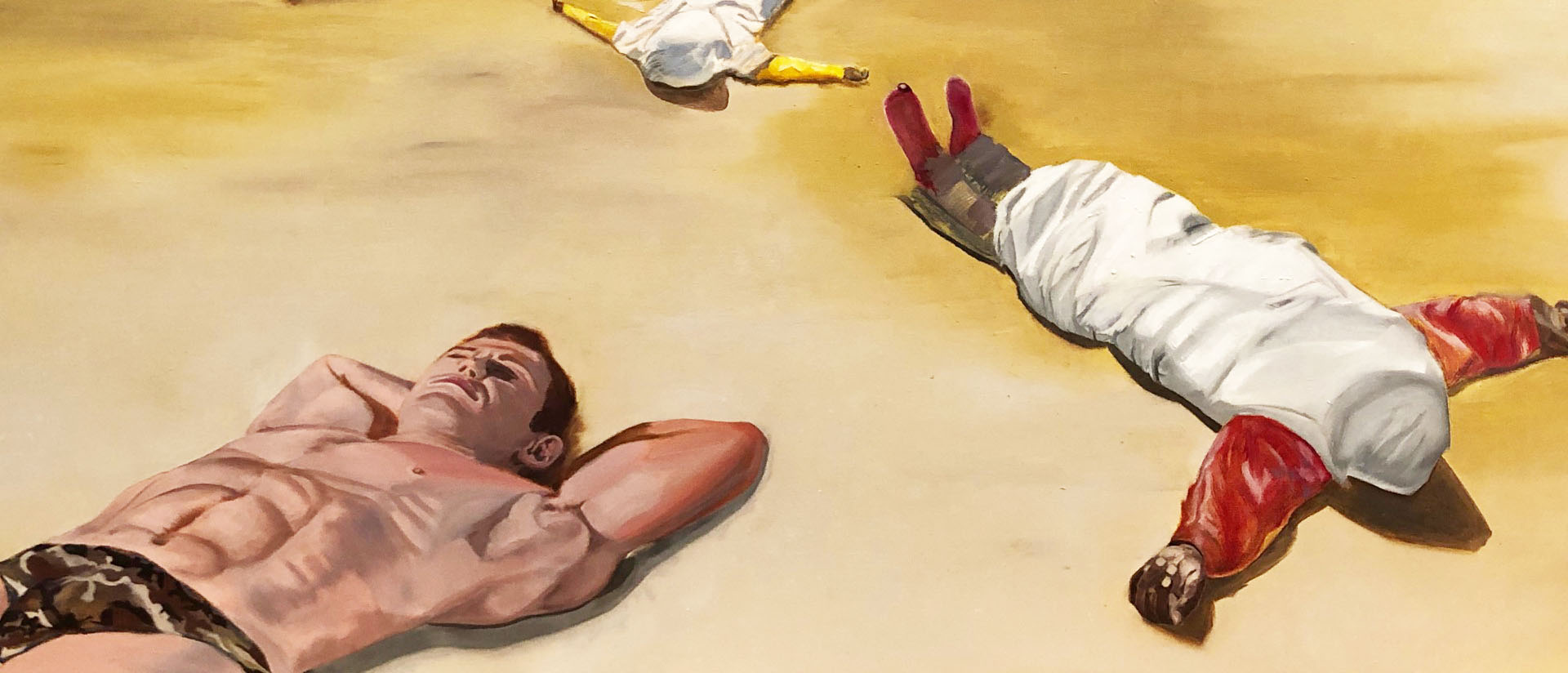

Image: Guqin players during the Tang Dynasty (618-907).