Menschenlandschaft

Traces of Turkish migration in West Berlin

by Ela Gezen

During a visit to the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Museum archive while doing research for my first book, Brecht, Turkish Theater, and Turkish-German Literature: Reception, Adaptation, and Innovation after 1960 (Camden House, 2018), I came across a catalogue featuring the exhibit Mehmet kam aus Anatolien (Mehmet came from Anatolia, 1975). It was organized by the Kunstamt Kreuzberg and the Türkischer Akademiker- und Künstlerverein— institutions unknown to me, and focused on the documentation of Turkish life and experiences in West Germany, from living and working to childcare and leisure, as well as Turkish economic and political realities prior to emigration. Beyond the display of photos, tables, and statistical information, the exhibit centered on artworks by three Turkish artists living in West Berlin: sculptor Mehmet Aksoy, painter Mehmet Hanefi Yeter, and ceramist Mehmet Çağlayan. All three “Mehmets” came to West Berlin as trained artists—not labor migrants— and were affiliated with the University of the Arts in West Berlin.

This exhibit catalogue became a starting point to examine additional cultural events that took place throughout the 1970s in West Berlin, predominantly in the Kreuzberg district. This led to further archival discoveries, including press coverage in German and Turkish newspapers of a hitherto unexamined spectrum of cultural activities and lively art scene, correspondence by artists, cultural, and municipal institutions, program and event brochures, and official documents. The latter provide insight into the conceptualization and funding structures for cultural work in the context of Turkish migration.

Turkish artists, intellectuals, and academics had founded numerous associations in West Berlin throughout the 1970s and ’80s, in order to establish institutional settings for cultural activities. One of them was the Türkischer Akademiker- und Künstlerverein, co-founded in 1972 as Akademikerverein der Türkei West-Deutschland—West Berlin by sculptor Mehmet Aksoy. The association’s initial focus on Turkish academic contexts was expanded in December 1974— evident in its name change to Türkischer Akademiker- und Künstlerverein—to include artists and to outline a position and goals within the cultural sector. The expansion of cultural offerings for Turkish labor-migrants and the facilitation of exchange between Turkish and German residents of West Berlin were central to the association’s cultural activities. As its chair, Aksoy was involved in a variety of collaborative projects with municipal institutions, such as the Kunstamt Kreuzberg, including a 1977 festival in honor of the Communist poet Nâzım Hikmet (1902–1963), for what would have been the poet’s seventy-fifth birthday.

Turkish artists, intellectuals, and academics had founded numerous associations in West Berlin throughout the 1970s and ’80s, in order to establish institutional settings for cultural activities.

Aksoy came to West Berlin in 1972 on a fellowship (he returned to Turkey in 1989), and West Berlin became an important setting for his work. His early sculptures center on the working class and working-class solidarity, as evident in two cycles: one focusing on unemployment and the other on demonstrations. In addition to collaborative and individual exhibits, Aksoy also participated in group projects such as the sculpture trail Menschenlandschaft Berlin (Human Landscape Berlin, 1985–1987), one of the few extant projects that has preserved his sculptures in Berlin’s contemporary cityscape.

Dedicated to Kreuzberg as a focal point for immigration, Menschenlandschaft Berlin stretches between Schlesische Strasse and the May-Ayim-Ufer—and for a good reason: Schlesisches Tor is one of the oldest developed spaces in Berlin and was once the location of the Schlesisches Stadttor (Silesian city gate), through which immigrants from Silesia entered the city throughout the eighteenth century.

One aim of placing art in this public space was to offer an opportunity for encounter and coexistence; another was to provide the immigrant population who lived there with reference points for their own histories. The art here would document their paths while also making them visible to West German residents.

The idea of bringing art in dialogue with Kreuzberg’s diversity in a public space had arisen earlier, in the late 1970s, in a conversation between Aksoy and art educator and director of the Kunstamt Kreuzberg, Krista Tebbe. On Tebbe’s initiative, individuals and representatives of various artistic, district, and planning institutions came together in a working group to explore potential concepts, locations, topics, and processes for such a project. The project itself was carried out through a collaboration among organizing and coordinating institutions, the jury, residents, the district administration, and participating artists.

Menschenlandschaft Berlin was embedded in the 750-year anniversary of the city of Berlin (in 1987) and commissioned by the Senator für Bau- und Wohnungswesen (Senate for Building and Housing). Artists were sought through a call for applications, yielding 82 submissions, eight of which were selected by a 13-person jury, led by sculptor Waldemar Otto, comprised of artists, architects, and representatives from institutions including the Senate for Building and Housing, IBA (International Building Exhibitions), Kunstamt Kreuzberg (Arts Council for Kreuzberg), the BVV Kreuzberg (district council Kreuzberg).

The conceptual phase of the project lasted a year and provided several opportunities for the public to follow its stages and participate in discussions during town hall meetings. Archival documents confirm high participation by Turkish residents, with the vast majority supporting the project. Participating artists presented six broader spatial concepts, which resulted in a majority vote for Azade Köker’s proposal, “Skulpturenweg zum Ufer” (Sculpture trail to the river banks) in December 1985.

The conceptual phase of the project lasted a year and provided several opportunities for the public to follow its stages and participate in discussions during town hall meetings.

Individual components were integrated into the entire concept and required extensive exchanges and coordination between participating artists (Mehmet Aksoy, Azade Köker, Andreas Frömberg, Louis Niebuhr, Andreas Wegner, Rudolf Valenta, and Leslie Robbins). A trail made from granite plates connected the individual components (as well as public spaces) physically and visually, which also engaged various aspects of immigration and coexistence (Miteinanderleben). Since the project’s inception, the relationship between art and its surroundings was a priority, foregrounding an engagement with the urban space over an intervention (and radical change of the environment), thus underlining the thematic and local integration of the chosen concept. In some instances, as in Aksoy’s case, this also involved working at the site itself. The title Menschenlandschaft Berlin was proposed by writer Ingeborg Drewitz, referring to Nâzım Hikmet’s multivolume epic Memleketimden İnsan Manzaraları (Human Landscapes from my Home Country), written between 1941–51 and published in 1966–67, which Hikmet conceived of as “poetic history of the present.”

Importantly, Menschenlandschaft replaced the working title Ausländer in Berlin (Foreigners in Berlin), due to its negative and discriminatory connotations. With its focus on “foreigners” in Berlin, the project aimed to draw attention to Berlin’s longstanding history of immigration, and in particular to address Turkish-German relations. The sculpture trail was envisioned as a place of encounter but also as a reference point for immigrants.

When you visit the Menschenlandschaft sculpture trail today, you will find its components heavily graffitied. Since reunification, traffic patterns and the spatial environment around it have also changed. And apart from the Hikmet inscription on one of Aksoy’s sculptures (an excerpt from his poem “Ellerenize ve yalana dair”/“About your Hands and Lies,” written in 1949 in Bursa prison), there is no identification of or reference to the artists, the project, its framework, or the historical relationship to the surrounding space in Berlin.

Aksoy’s marble sculpture cluster Labor Migration is located between Schlesische Straße and Oberbaumstraße and represents the stages of immigration through the varied placement of figures in relation to the trail. These invite visitors to reflect on the artistic working methods of a stone sculptor. The direct-carving exposes something that would otherwise remain hidden from the viewer, offering a connotation inherent in the sculpture’s materiality. And since direct carving is a laborious process, it also emphasizes “labor” in its various interpretive guises, in addition to the “labor migration” in Aksoy’s title.

Namely, transforming a piece of stone into a sculpture points to the process of simultaneous unveiling and trace-leaving, underlining the intersection of temporality, sculpture, and artist. On the one hand, processing the stone makes something visible in the literal and allegorical sense, on the other hand, Aksoy suggests a continuation of time, and thus the past(s), in the sculpture. Moreover, his multi-part ensemble consists of partially polished and partially raw carved marble, which in addition to the thematic consideration of stages of migration— from departure to arrival to potential settlement—provides further contrasts and underlines processes inherent to migration. Migration is thus represented in its various stages with figures standing next to, moving toward, or intersecting with the path, and at the same time carved into stone and thus preserved for, and into, the future. As such, Aksoy’s sculptures in the cityscape of Berlin invite us to follow the traces left behind and to engage with the memory of migration.

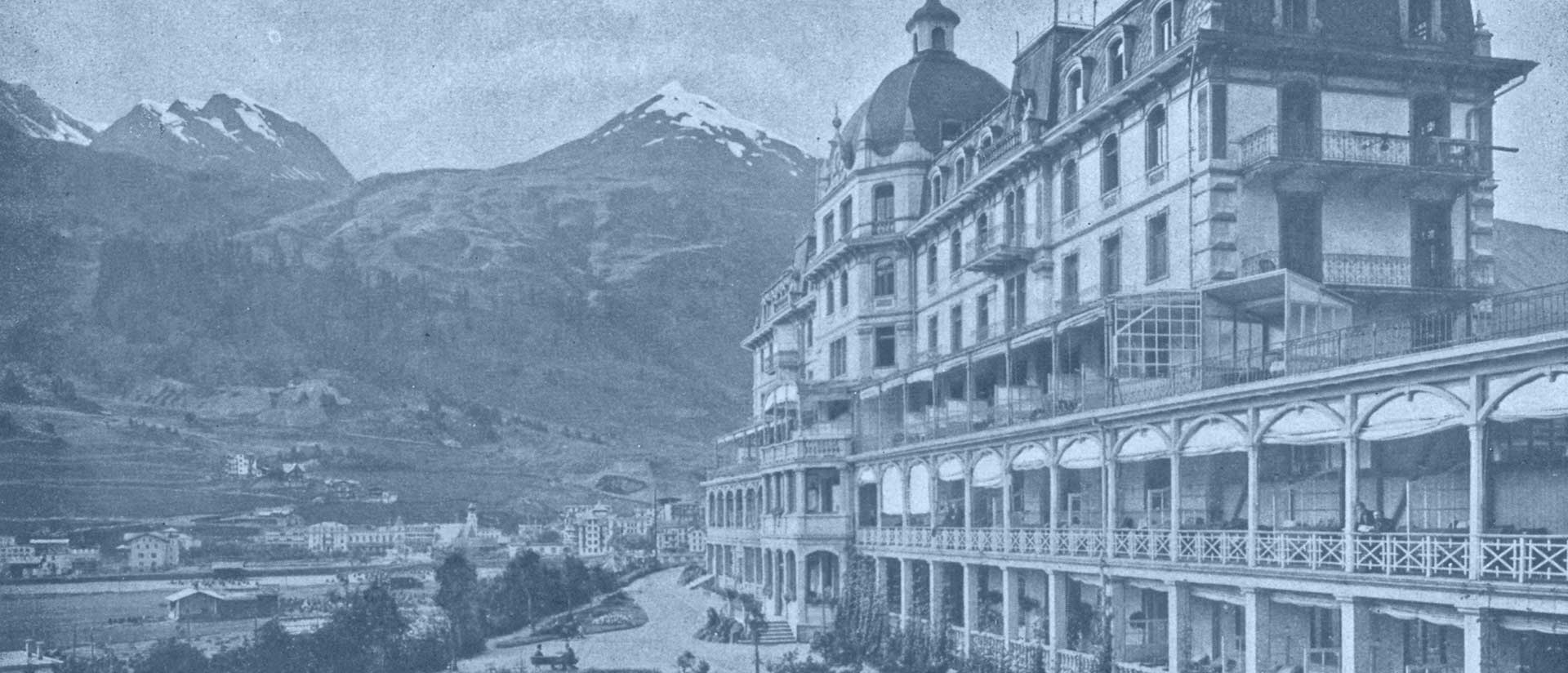

Photo: Public art at Oberbaumstraße, November 27, 1987. Photo: Jürgen Henschel. Courtesy FHXB Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Museum