American Democracy’s Polycrisis

The Supreme Court and the future of democracy

by Joshua Sellers

Standard descriptions of the multifarious threats to American democracy—illiberal, regressive, antidemocratic—are, though accurate, all seemingly inadequate in describing the gravity of the moment. In truth, we lack a sophisticated conceptual vocabulary for chronicling the country’s slow yet steady democratic deterioration.

Such deterioration takes many forms. Half of the country believes that the last presidential election was stolen; the other half fears it is too late to prevent the theft of the presidential election to come. Congress, long defined by its dysfunction, failed to enact legislation to protect voters from discrimination and vote suppression, both of which are resurgent. The Supreme Court, firmly controlled by its conservative wing, thwarts representative democracy as a matter of course. The unmistakably malignant political violence of January 6, 2021, engendered not, as one might hope, a national reckoning, but further recriminations and division. And throughout the states—our great laboratories of democracy—dubious partisans are maneuvering into positions of electoral authority, increasing the risk of partiality, or worse.

This constellation of concerns calls to mind the French philosopher Edward Morin’s concept of “polycrisis.” This idea—later adapted by former president of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker and, more recently, by the historian Adam Tooze— posits that certain “interwoven and overlapping crises,” as Morin said, can only be understood holistically. In other words, emphasis on only a single crisis ignores, at the risk of incomprehension, the “intersolidarity” of the crisis landscape. This framing might help us delineate, if not remedy, the interconnected crises imperiling our democratic future.

How did we reach this point? In offering a diagnosis, it is tempting to concentrate on the preposterousness of one man. If Donald Trump were the exclusive source of our inquietude, our interpretive task would be much simpler. There is no shortage of egotistical, boorish figures in American political history, even if Trump might be denominated the chieftain of the lot. But our problems far exceed the nefariousness of the former President. As brilliantly observed by writer Fintan O’Toole, “One of the reasons there cannot be a postmortem on Trumpism is that Trumpism is postmortem. Its core appeal is necromantic. It promised to make a buried world rise again.” So, while Trump’s outsized influence on American politics is noteworthy, the quest to renovate a buried world is the source code of American democracy’s polycrisis. At present, this is perhaps most intelligible through the lens of our ostensibly apolitical branch of government, the judiciary.

There is no shortage of egotistical, boorish figures in American political history, even if Trump might be denominated the chieftain of the lot. But our problems far exceed the nefariousness of the former President.

In the months ahead, the Supreme Court will issue decisions in two momentous election law cases, each of which may transform American democracy in radical ways. Legal technicalities aside, both cases illustrate the intersolidarity of our crises. Consider first Merrill v. Milligan, which involves the perennially contestable redistricting process. As background, every ten years, states are obliged to redraw both their federal and state electoral districts to account for the prior decade’s population changes. For decades, under the prevailing interpretation of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA), states have been required to create “minority-opportunity” districts when certain conditions are met. In short, when minority voters comprise a sizable portion of a geographically compact area, are politically cohesive, and have historically been unable to elect their “candidates of choice,” the obligation to create a minority-opportunity district in which a minority- preferred candidate will likely be elected may arise. This obligation reflects a national commitment to constructing an inclusive, multiracial democracy, one in which our federal and state legislatures reflect our country’s great diversity. This is a decidedly modern commitment, an instantiation of the progress we’ve made since the days when racial political terror was, in many places, customary. Alabama was notorious as one such place.

Today, Alabama has seven congressional districts, and Black Alabamians comprise approximately 27 percent of the state population. In November 2021, the Republican-controlled Alabama legislature enacted a new congressional map that contains one majority-Black congressional district yet divides a large segment of the Black community among several other districts. This tactic—a common form of minimizing the electoral influence of minority voters—provoked a VRA lawsuit that resulted in a federal district court striking Alabama’s map, and ordering the state to create a replacement map containing two majority-Black districts. Yet, before that process began, the Supreme Court stayed (i.e. suspended) the district court’s decision and announced its intention to rule on the merits of the case. The merits here are no less than the future of the VRA. Conservatives, including those on the Supreme Court, have long despised the VRA’s express attention to race. Race is, to their minds, an unwelcome social and political category. When fore- grounded, they claim, it frustrates the goal of national unity. This superficially appealing yet rudimentary logic is best encapsulated by Chief Justice John Roberts’s claim that “[t]he way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” The subtext here is the headline: race-consciousness in law or policy is akin to discrimination.

By agreeing to hear Merrill on the merits, the Supreme Court appears poised to strip the VRA of its remaining force. The most incredible outcome would be an opinion finding the VRA unconstitutional, though such a brazen determination is unlikely. More likely is an opinion that effectively nullifies the VRA by disingenuously likening the consideration of race in redistricting (an inevitability, whether transparently or surreptitiously) to overreliance on race in redistricting. In other words, and as Alabama argues, creating a congressional district map with two majority-Black districts would itself violate the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause, because doing so would require overreliance on race and, repeating a line from above, race- consciousness in law or policy is akin to discrimination. If this argument succeeds, states like Alabama will be free to manipulate their electoral districts to the detriment of minority voters (and to the benefit of the Republican Party), all while claiming adherence to the principle of race- neutrality. The consequence would be far fewer minority-opportunity districts across the country, and more pointedly, as put by one of the briefs, the facilitation of “white-dominated state governments and congressional delegations, Black disenfranchisement, and racial apartheid.” So, while lamentations about the reification of race in America always seem to find an audience, in the trenches of American law and politics, race-consciousness remains an essential bulwark against entrenching injustice. In deciding Merrill, the Supreme Court will reveal its vision for America’s political future. We should desperately hope that its vision is not a resuscitation of the pre-1960s, pre-VRA past.

While lamentations about the reification of race in America always seem to find an audience, in the trenches of American law and politics, race-consciousness remains an essential bulwark against entrenching injustice.

The second case, Moore v. Harper, is potentially even more consequential. At issue is the extent of state legislatures’ power over federal elections. The relevant background is somewhat intricate. Article I, Section 4 of the Constitution contains what is known as the “Elections Clause.” This pro- vision states that “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Place of Chusing Senators.” The text, then, empowers state legislatures, unless overridden by Congress, to regulate the times, places, and manner of federal elections (no one denies that states may regulate the times, places, and manner of state elections). The question presented in Moore is whether state legislatures are exclusively empowered to do so.

Once again, the relevant facts arise from the redistricting context, though the implications of the case go beyond that arena. As was true in Alabama, the recent round of redistricting in North Carolina provoked litigation. That litigation culminated in an opinion from the North Carolina Supreme Court, holding that the congressional district map enacted by the Republican-controlled North Carolina legislature constituted partisan gerrymandering (i.e. the manipulation of electoral district lines to unfairly benefit one political party) and there- fore violated the state constitution.

In challenging that holding, the state legislature is now arguing in the Supreme Court that the Elections Clause—which, again, expressly empowers state legislatures—precludes the North Carolina Supreme Court from invalidating its congressional map.

The most muscular version of this argument suggests that no other state actors (e.g. a governor, a secretary of state, state-court judges) can override or limit the power of state legislatures when it comes to regulating federal elections. As far-fetched as this argument might sound, multiple Supreme Court Justices have expressed support for it. For instance, in related litigation, Justice Samuel Alito wrote: “The provisions of the Federal Constitution conferring on state legislatures, not state courts, the authority to make rules governing federal elections would be meaningless if a state court could override the rules adopted by the legislature simply by claiming that a state constitutional provision gave the courts the authority to make what- ever rules it thought appropriate for the conduct of a fair election.” If four other Justices agree, two centuries of election law will be upended.

As is apparent to any passing observer of American politics, many state legislatures are currently bastions of ultraconservatism, acting in aggressive pursuit of retrograde political goals, including the suppression of minority political participation. A broad ruling for the North Carolina legislature in Moore would validate these efforts and encourage further attempts to dis- qualify and discourage select groups of voters. Even a narrow ruling for the North Carolina legislature limited to the facts of the case might prevent state courts from invalidating egregious partisan gerrymanders, thereby eliminating partisan gerrymandering claims altogether (such claims are already “nonjusticiable” in federal courts). Either outcome would be calamitous.

Many state legislatures are currently bastions of ultraconservatism, acting in aggressive pursuit of retrograde political goals, including the suppression of minority political participation.

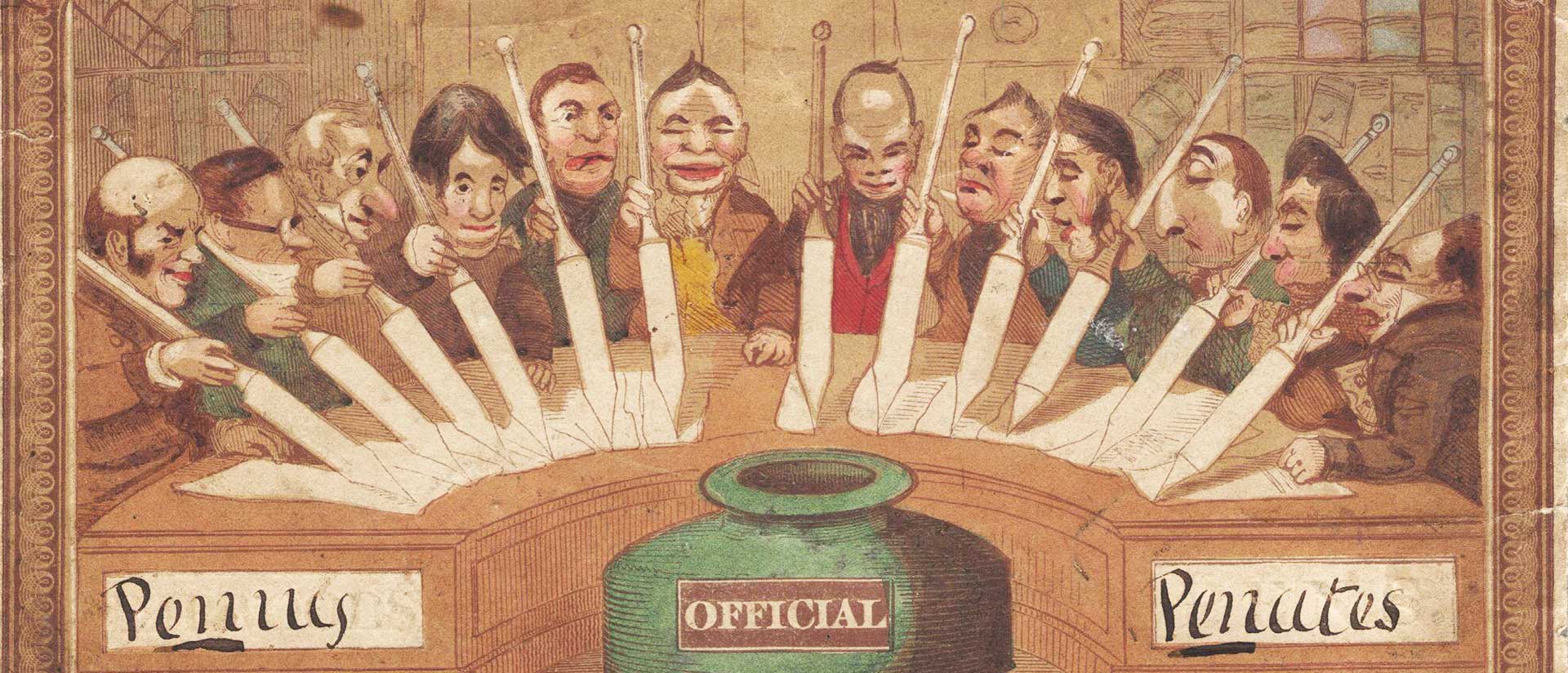

Moore is a curious addendum to a long-running national story about state legislatures’ power to shape American politics. The closest historical analogue is found in the first half of the twentieth century, when state legislatures enjoyed largely unfettered control over the design of their electoral districts. For decades, that unchecked power was abused. The gross malapportionment of the era—in Tennessee, for example, county populations ranging from 2,340 to 25,316 were afforded the same level of representation in the state legislature— systematically favored sparsely populated rural communities, thereby rendering it impossible for electoral majorities to correct the problem through the normal political process. The Supreme Court’s landmark “one- person, one-vote” decisions are widely celebrated for rectifying this inequity and advancing a vision of American democracy in which the equality of votes is paramount. It is worth recalling this history, and the necessity of oversight and checks-and-balances, as state legislatures once again seek autonomy over elections.

Taken together, the disputes at the heart of these two cases encapsulate our democratic polycrisis. A responsible Congress could preempt the worst possible outcomes in both Merrill and Moore, but Congress is idle. An unbiased Supreme Court committed to political equality as a Constitutional aspiration, and deferential to precedent, would easily reject the radical claims presented by the Alabama and North Carolina legislatures. Regrettably, that is not the Court we have. Voters could, in theory, punish state legislators at the polls for compromising representative democracy. Yet voters are highly polarized and prone to the same antagonisms as their representatives. And so, we carry on, uncertain about solutions but at least cognizant of how these crises intersect, braced for the fights ahead.