Impossible Proximity

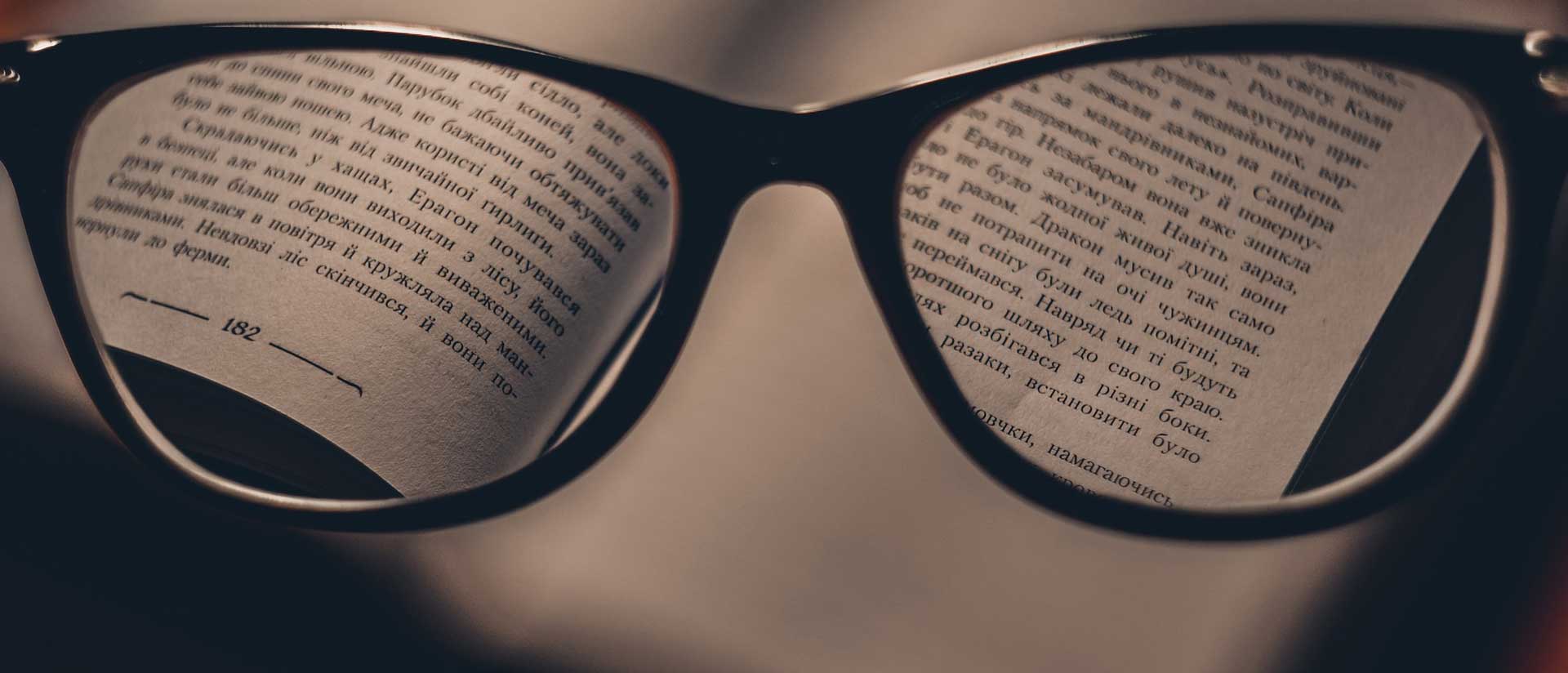

How to read like Nabokov

By Tatyana Gershkovich

In Zadie Smith’s 2009 essay “Rereading Barthes and Nabokov,” a battle plays out for the soul of the reader. She begins with two epigraphs:

The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author.

– Roland Barthes

A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a rereader.

– Vladimir Nabokov

Barthes celebrates the reader’s unlimited interpretive freedom. Nabokov, in contrast, insists the text’s meaning remains in the custody of its author; the reader can only hope to approximate it through diligent, effortful rereading. As a college student, Smith read in the Barthesian way, enjoying readerly free reign. But reading like Barthes made her “feel lonely.” It meant to “jettison the very idea of communication, of any possible genuine link between the person who writes and the person who reads.” The Barthesian mode now fails to satisfy her as both a reader and a writer, as someone who “[feels] the need to believe in [writing] as an intentional, directional act, an expression of an individual consciousness.”

The loneliness Smith felt will be familiar to other readers trained in the wake of poststructuralism and deconstruction. Well-versed in the inherent instabilities of language, these readers—that is, we ourselves—no longer trust a text to convey a message from author to reader. We have become “suspicious” readers, readers for whom the text is always deceptive—either intentionally, because the author seeks to manipulate the reader, or unintentionally, because the meaning of what she writes is determined by her class interests, her repressed sexual urges, the discourse of her times. But our suspicious hermeneutic practices are, as Smith intuited as an undergrad, unsatisfactory; they are inadequate to all of our readerly needs. Our suspicion deprives us of one of the chief pleasures of reading: the sense that in reading we come to know a consciousness other than our own. In Nabokov, Smith sees the potential to reinstate this pleasure.

We have become “suspicious” readers, readers for whom the text is always deceptive—either intentionally, because the author seeks to manipulate the reader, or unintentionally, because the meaning of what she writes is determined by her class interests, her repressed sexual urges, the discourse of her times. But our suspicious hermeneutic practices are [. . .] unsatisfactory.

But I wish to propose a correction to her view of a confident Nabokov confidently connecting with his readers, serenely doling out literary delights. It seems to me that in seeking relief from Barthes, Smith fails to appreciate the way in which Nabokov’s mode of reading is also shaped by skeptical doubt, even if his reaction to that doubt is very different from Barthes’s. Nabokov’s fiction and criticism can best be understood as a distressed response to his own skepticism—to what might be called (after Stanley Cavell) his skeptical disappointment.

As other scholars have observed, Vladimir Nabokov’s quasi-scientific approach to reading in many ways resembles that of the Russian Formalists. He, too, believes that art is not a faithful reflection of reality, but rather a “distorted (‘shifted’) image of the object in reality,” as Berkeley Slavicist Irina Paperno has written. He, too, attends foremost to an artwork’s materiality, to its structure and language, to its “how,” not its “what.” He, too, rejects the idea that a literary work furnishes us with knowledge of the historical, political, sociological, or biographical variety. “I am sick of reading biographies in which mothers are subtly deduced from the writing of their sons and then made to ‘influence’ their remarkable sons in this or that way,” he wrote in his 1944 book on Nikolai Gogol.

But Nabokov’s empiricism is different from that of the Formalists. It is both more stringent and more peculiar. The “information” he is after—and indeed, that word appears frequently in his discussion of his method, which aims, he wrote in Strong Opinions (1973), “to provide students of literature with exact information about details”—is information of a rather idiosyncratic kind. Any Formalist would agree with him that an analysis of Gogol’s use of adverbs and prepositions is important for understanding his story “The Overcoat” (1842). But Nabokov’s need to “clearly visualize” the arrangement of Anna Karenina’s train compartment—the impossibility, as he says in Lectures on Russian Literature (1981), of “comprehend[ing] certain important aspects of Anna’s journey without it”—would exceed the requirements of most Formalist analysis. Moreover, few have found Nabokov’s diagrams of the Samsa household and his drawings of Kafka’s insect (“a domed beetle, not the flat cockroach of sloppy translators”) helpful in understanding The Metamorphosis, let alone indispensable, as Nabokov insisted. And many critics have taken Nabokov to task for the sort of “exact information” he offers in the commentary to his 1964 translation of Alexander Pushkin’s famed 1833 novel Eugene Onegin. Here, in addition to making useful literary-historical observations, Nabokov expounds at length on the layout and dimensions of Pushkin’s Boldino estate, including the lilacs surrounding the manor house. We are instructed, in his Lectures on Literature (1980), to “notice and fondle details.” But what sort of purpose do such details serve? They hint, I think, at the objectives of Nabokov’s mode of reading.

The desire to know what sort of insect Kafka saw in his mind’s eye or what sights and scents surrounded Pushkin during his stays as Boldino suggests an aim beyond determining how a text functions. Readers ought to “discover,” as Nabokov puts it, “a definite order in the system of [a text’s] gaps and odd perches—and this order is characteristic of the author’s individual style.” And for him, an individual style is coextensive with an author’s identity: “A writer’s art is his real passport,” he writes in Strong Opinions. “His identity should be immediately recognized by a special pattern or unique coloration.” In other words, what Nabokov aims to discover, if not inhabit, is the authorial consciousness. This is a task anathema to Formalism. Indeed, it harkens back to an earlier form of criticism, a kind that was practiced by the literary critic Iulii Aikhenvald (1872-1928), Nabokov’s friend and mentor in émigré Berlin.

What Nabokov aims to discover, if not inhabit, is the authorial consciousness. This is a task anathema to Formalism.

A neo-Kantian critic active in the first three decades of the twentieth century, Aikhenvald has now been largely forgotten, partly thanks to the disruption of his work due to his exile, in 1922, from the Soviet Union. But he was well known to his literary peers, particularly for his multi-volume work Silhouettes of Russian Writers, which came out in five editions between 1906 and 1928. Aikhenvald’s criticism remains noteworthy for the challenge it posed to the scientism of emerging Formalism.

Aikhenvald held that the literary text is a meeting of two souls—the author’s and the reader’s. It is the formation of a “spiritual dyad.” He describes how in reading Pushkin’s poetry, for example, we nearly merge with the poet himself: “In his poetry, Pushkin told his biography in such a way that this biography became all human,” he wrote in a 1906 essay, “change the names, individual details and facts, and it would be you.” After cataloguing a few of Pushkin’s devices, Aikhenvald insists that any attempt to dissect Pushkin’s poems is hopeless. To understand Pushkin, “one has to simply read him,” to immerse oneself in the “very flow, the resounding joy of his poetry.” Nabokov, for whom art is the expression of a unique and creative mind, rejected the Formalist notion that an artist is a “vehicle not [an] agent,” as Nabokovian Michael Glynn put it. He shared Aikhenvald’s sentiment that an aesthetic experience is a communion between author and reader, famously describing it, in Lectures on Literature, as a “spontaneous embrace.”

Their aspirations of communion notwithstanding, neither Nabokov nor Aikhenvald had illusions of actually attaining any certain knowledge about another’s meaning, let alone his psyche. But whereas Aikhenvald celebrates this uncertainty, Nabokov finds it hard to abide. For Aikhenvald, “the word is elusive, the word is obscure, and we readers do not understand it in the exact way the author meant it,” he writes in his essay “The Writer and the Reader,” published in 1922. “Only there is no calamity in this—the reader must augment the author or else there would be no literature.”

Aikhenvald argues that as long as the reader does not deliberately distort the author’s work, he should not be ashamed of or deny his subjectivity: “Everyone has a right to himself,” he notes in Silhouettes. Aikhenvald suggests that our goal as readers is to articulate how a text draws out our own judgments and attachments. Nabokov, in contrast, concedes that our aesthetic impressions are always subjective—“everything worthwhile is to some extent subjective”—but insists, in Lectures on Literature, that “the reader must know when and where to curb his imagination and this he does by trying to get clear the specific world the author places at his disposal.” To the extent possible, the reader is to investigate the author’s world. Aikhenvald stressed the reader’s subjectivity, Nabokov the need to restrain it.

“There is no calamity in this”—perhaps not for Aikhenvald, but Nabokov continued to long for certainty about others, a certainty he knew would always elude him. In this, he resembles the Cavellian skeptic. On Stanley Cavell’s account, the skeptic who bemoans our inability to know other minds the way we know our own is disappointed not by an epistemological deficiency but rather by our metaphysical separation from one another. The problem for the skeptic is not that I can never know everything there is to know about, say, the quality of your pain; one can imagine a world in which I could do so. The problem is that even if I were to know all about your pain, it would still be your pain and not mine. What the skeptic means is therefore something like: “I do not acknowledge [your pain] the way you do; I do not acknowledge it by expressing pain.” I cannot relate to your pain as you do. Your pain cannot be my pain, and vice versa. The skeptic turns what is, in fact, a tragedy of the human condition into an epistemological problem. The only way to solve the problem would be to achieve a perfect identity with another; yet such identity—even if it could be achieved—would deprive us of the very “otherness” that makes the problem coherent in the first place. Achieving the kind of identity the skeptic longs for would mean collapsing into solipsism, not transcending it. The problem of other minds will thus always remain a problem; and the skeptic who feels it to be a problem at all will always be disappointed.

Achieving the kind of identity the skeptic longs for would mean collapsing into solipsism, not transcending it. The problem of other minds will thus always remain a problem; and the skeptic who feels it to be a problem at all will always be disappointed.

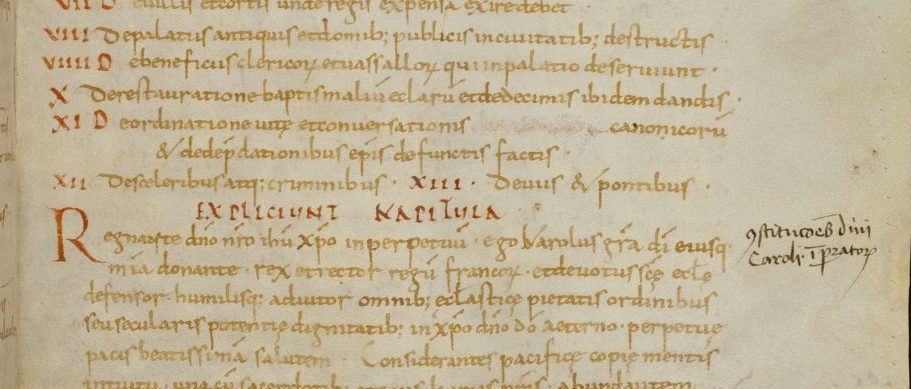

Nabokov’s disappointed desire for such identity is manifest in many of his fictions, and also, vividly, in his most ambitious critical endeavor—the commentary to Eugene Onegin. In his early essay “Pushkin, Truth, and Verisimilitude” (1937), Nabokov attempts an Aikhenvaldian approach to Pushkin, even echoing Aikhenvald’s rhetoric: “Nothing is more tedious than describing a poetic legacy that defies description. The only acceptable method to know it is to read it, to ponder over it, to discuss it with oneself.” Yet when he returns to Pushkin years later, Nabokov does describe it in painstaking, often esoteric detail. Nabokov’s stated purpose was to enable Anglophone audiences to read Pushkin. But the excess of the commentary—an excess that, in fact, makes it hard for an English reader to appreciate the poet—suggests that Nabokov is driven by a different desire. His wish for an impossible proximity with an other—with an author—results in the idiosyncratic and seemingly gratuitous empiricism that he demands of all readers, including himself. His stringent empiricism—so often mistaken for the whim of a haughty aristocrat—represents the disappointed desire for an impossible proximity with others.