The Young Man Who Sells Antiques

Fiction by Jesse Ball

I, Dermot More, was a seller of antiques, which is to say that I was lucky enough to work in an antique store, and to have obtained some knowledge about the past, and about the things of the past, enough knowledge at least to allow me to speak on behalf of these objects, and convince customers to buy what would otherwise be mere curiosities, but which, after careful description, become necessities.

A home must be filled with meaning, I always say—and some of it must come from your life. But some may come from the lives of others. Admit that light, if you are brave enough. That is one of my pitches.

I worked at the antique store every day. It is a special store. The rules of the store are, it is open when I am there, or when the old man is there, and if we are there we will sell you something if you want to buy it and if we like you. We try to be there as much as possible. It is a store where sales are rare. We might sell one item per day. That would be pretty good. So, a lot of the time we sit around, the old man and I, or the old man sits alone or I sit alone, and no one comes in at all.

But, there is a light on! There is the street with its bent black metal lightposts and the narrow glass windows of the shops, and at the end, our shop, with its light on—and you may come in if you like. If you do, if you did—then we would perhaps say nothing at all to you. You’d come in and the door would shut softly behind you.

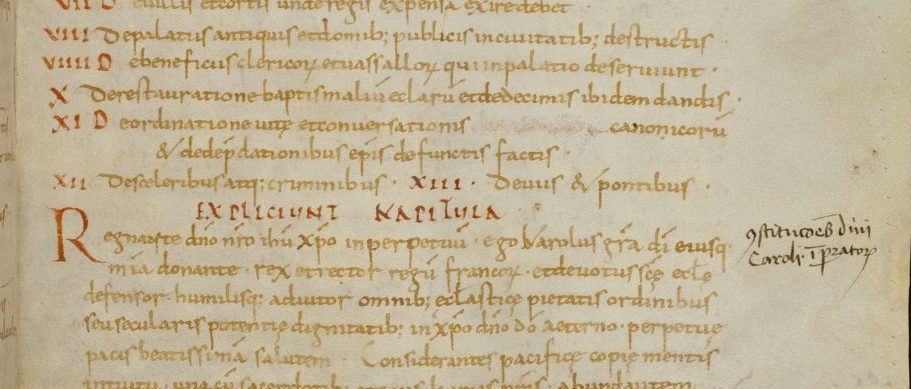

Ahead you would be confronted by a series of beautiful cabinets. Each cabinet has on the outside a thin and perfectly painted script and written in that thin and perfectly painted script a set of words, and described by those words, the contents of the cabinet. You may purchase the contents if you like, and you may ask to have the cabinet opened if you like. You may also open the cabinet if you like. The key is actually in the lock waiting to be turned, and that stands for every one of the 64 cabinets.

At our antique shop, we have 64 cabinets, and each one contains an antique that may be purchased. When one is bought, we replace that with another antique from our stores. Those antiques that are not in cabinets may not be bought, not for any price. This is the understanding that exists between ourselves, the antique shop proprietors, and the antiques themselves. They must wait their turn.

Of course, I am taking quite a bit on myself by saying I am one of the proprietors. In fact, I am a sort of glorified servant. I serve in the antique shop only at the behest of the actual owner and his wife, either of whose displeasure would immediately and permanently disqualify me. At such a time, I would be given a little sack with some payment and sent off. Although this has never happened, I have often imagined it happening, as I sit through the late hours of the night in the window of the antique shop.

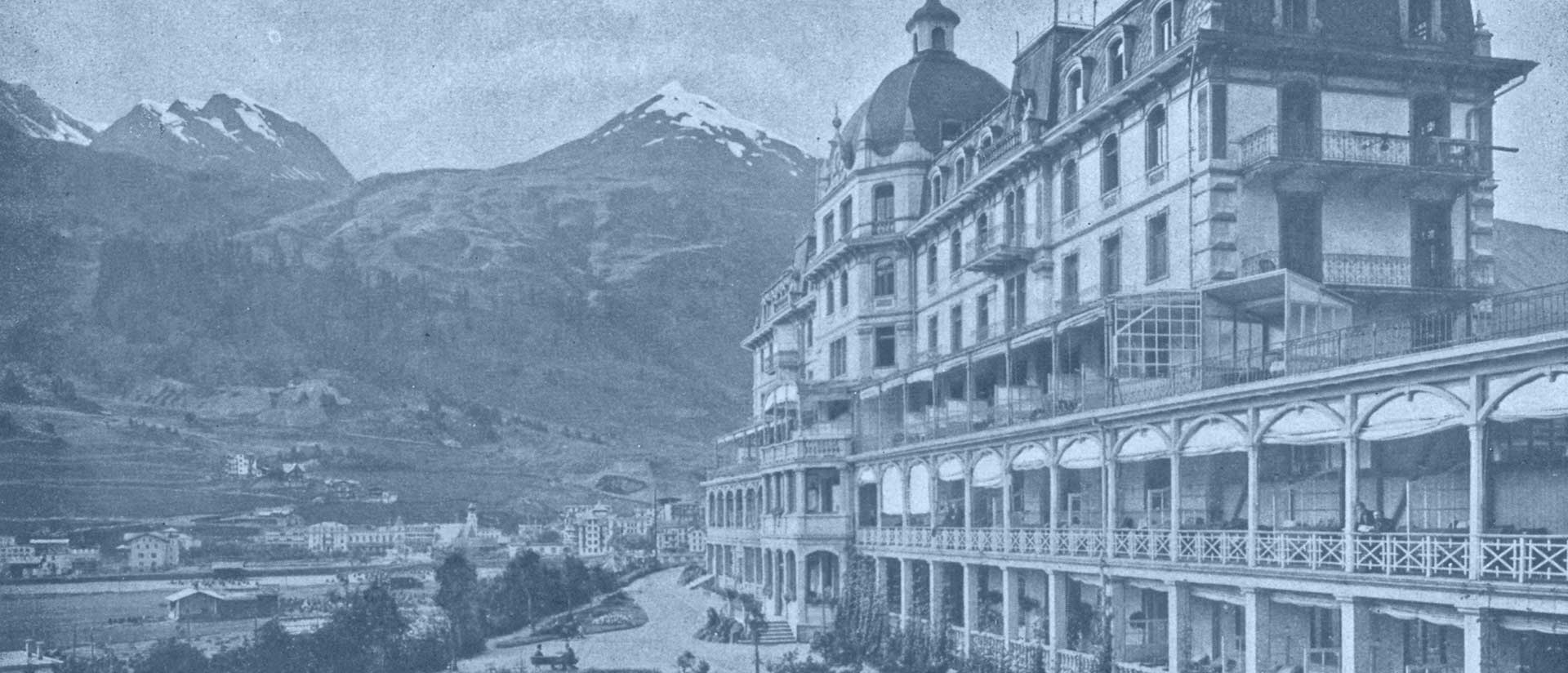

Part of the charm of the antique shop is that the proprietor of the antique

shop, or the attendant, if you will, sits in the very window where he may be observed by anyone going up and down our little street. Of course, no one ever does go up or down that street. The only reason would be to come to the antique store. Everyone who lives in the houses of the street, which are many and grand, has reached such an age that they go nowhere and see no one. They are huddling against the warmth of their final moments. This gives the street some of its old-fashioned charm.

How do I remember the days? Whenever anyone asks me this, I say—I do not know what day it is. I never do. But I always remember what I sold. And 24 days ago, the thing that I sold was:

a red bird.

It was a painted bird, very small. The bird was made from wood. It was carved from several notched pieces that fit together without glue. The style of the bird was this: it was a stylized bird. A bird, for instance, would not recognize it (the antique) as a bird, even were the [painted] bird to be made alive (which, of course, is impossible). The bird was rounder than birds are, and the beak was pointy in a needle-like way. The eyes were large and oval and not as precisely placed as an actual bird’s eyes would be. By this I do not suggest that there is a moment wherein someone places an actual bird’s eye. I know that no one does that. Case number 53 holds the red bird. The bird is made of wood and covered in paint. What is special about the red bird has to do with the paint. Twenty-four days ago, I sold the red bird to a young man. This is how it went:

a young man entered the store at about one in the morning. I was sitting in the window listening to a radio broadcast on a small table-radio set. The radio broadcast was an afternoon concert in a Moscow home, chamber music. I believe the concert had been held some fifty years ago. The broadcast was exceedingly pleasant and delivered everything one would want from such a broadcast. Occasionally there were interviews in Russian, which were pleasant to the ears of one like myself, who does not speak Russian. Above all, I hate hearing stupid things said in my own language, and so I much prefer to hear people speak languages I do not understand. That way, I can receive their fellowship without noticing their delusions.

In the midst of this fine broadcast, the door opened and shut. There in the shop was a young man in an overcoat. I did not look at him. He went up and down the aisles for some period of time and finally approached me.

He stood near me and I sat, looking fixedly at the table. I did not move my gaze from a small point there, a small point there on the table. It is an old piece of furniture, and there are many pits and cracks. Perhaps two-thirds of the way across, there is a sort of stamped depression, and within the depression, a coin-shaped scratch. That is the place that I often look at when I wait for customers to go far far out of their way in order to get my attention. Although I can’t say for sure that I was looking at that spot, I am nearly positive that I was. It is the only spot for a time like that. Perhaps for other employees of the shop there could be a different spot on the table, but for me, no. I discovered that point on the very first day I was employed, and have used it effectively ever since as a sort of stoic cloak that keeps the respectability of the shop unblemished.

Anyway, the young man stood there, and listened to the radio broadcast for a little while. The music stopped, and there were just Russian voices coming out of the little box.

At some point, the voices began to laugh, and the young man laughed too.

Don’t you think it’s funny? he asked me. That was quite a joke.

Can I help you? I asked this young man. Either it was nonsense—he did not know Russian, or he did. Either he thought the joke was funny, or he did not. Either his remark was, in absolute essence: I am a person of interest, please believe me, or it was, together we share having heard X where X is a joke made by a now-dead musician. It might as well be accepted as the latter, I suppose. Shouldn’t we always enjoy the finest world we can? Even if it is in parts shattered and imaginary?

I would like to look at one of the cabinets. Which one, I said. Any of them, he said. Number fifty-three, I said, holds the red bird. I would like to see it, then. Come with me.

We went down the aisle to number 53. The cabinets are not in order. The first thing one has to do as an attendant in the antique store is to learn the order of the cabinets. Equally, one could say, it is never important to know the order of the cabinets, as that knowledge can never once actually be put to use—or never is. All the same, we attendants like to pride ourselves on knowing the numbers. By that I mean, when I have thought about a conversation that I would have with other attendants, of which there are none (there is only the proprietor and myself), I have often considered little in-jokes and statements that we might make in perfect confederacy of understanding. One of these involves the necessity of understanding the order of the cabinets. I can draw a map at any time of the cabinets and also write out verbatim all the descriptions of the cabinet contents. I can do that not only for the current collective offering of the shop, but for every collective offering that we have made in the last five years. We attendants do not believe this to be a special skill or even notable, and I do not tell you this now in order to brag, but merely in order to be clear about what the job entails, should you consider applying for it, or for another job like it. I say that, but I don’t believe there is another job like it. Although I am not vain about myself, I am certainly prideful about the shop. It is simply the greatest antique shop there has ever been. No shop of any sort comes close to it.

Enough about that. Also, I am forced to take back the final part of that paragraph as it breaks the rules of composition. I who have not been in every shop in the world cannot say it truthfully. I will restate: to this poor attendant of an antique shop who has scarcely gone anywhere on the globe, it appears to be an unquestionable fact that the very antique shop in which he labored is the finest in the land.

I led the man to the fifty-third cabinet.

Before I open this cabinet, I must tell you, I said. The bird is non-notable. Please confine your comments and questions to the paint that has been used to cover the bird.

I opened the cabinet.

Very good, he said. Very, very good. The price is?

Considerable.

I will pay with a check. But first, let me ask you: the paint…

My friend, we do not simply sell these objects. You must, of course, in one way or another apply to purchase them. In this case, please, if you don’t mind, explain to me why you should like to be the owner of this bird.

A note here about the antique shop: the owner has sufficient wealth to live until his death. He does not require more. The shop is merely a way for him of interacting with the world. As such, he will only permit his goods to go to worthy purchasers. This was impressed upon me thoroughly at the time of my job examination. What is the ideal customer? was met with my answer (of which I am rightfully proud):

The ideal customer is the actual owner of the object, who is chronologically displaced from his ownership. It is our job to bring these time-periods into alignment.

We, therefore, attempt to investigate the character and rationale of our customers, especially by asking them to speak. As example, I bring the young man’s speech from the red-bird sale, which went something like this:

There is a story, said the young man, that is told about me by my grandfather. The story was told by him before I was born, and he continues to tell it to this very day. Here it is:

he says that a child who whistles like a bird is always in danger of being shot, whether in a house or out in the woods. He says that he has both been this child (been shot), and been the one who has shot the child. He says that under no circumstances should children be taught to whistle, and if they are taught to whistle, then they should never never be taught to whistle like a bird. Of course, my grandfather taught me when I was very young how to whistle just like a bird.

The young man made a short sharp whistle. If I hadn’t been watching him, I would have suspected a bird had come into the shop. Indeed, even looking at him, it was no longer so clear—was he a bird dressed as a man? Oh, I’m just joking with you now. I know very well that he was just an antique-buyer.

So, he taught you to whistle like a bird?

He did, and then this.

The young man pulled down the collar of his coat to show me a scar that ran across the side of his neck.

I was shot once, while sitting on the lawn of my uncle’s house. I was shot while whistling.

We sat there for a moment and I felt that it would be acceptable to sell this young man the red bird.

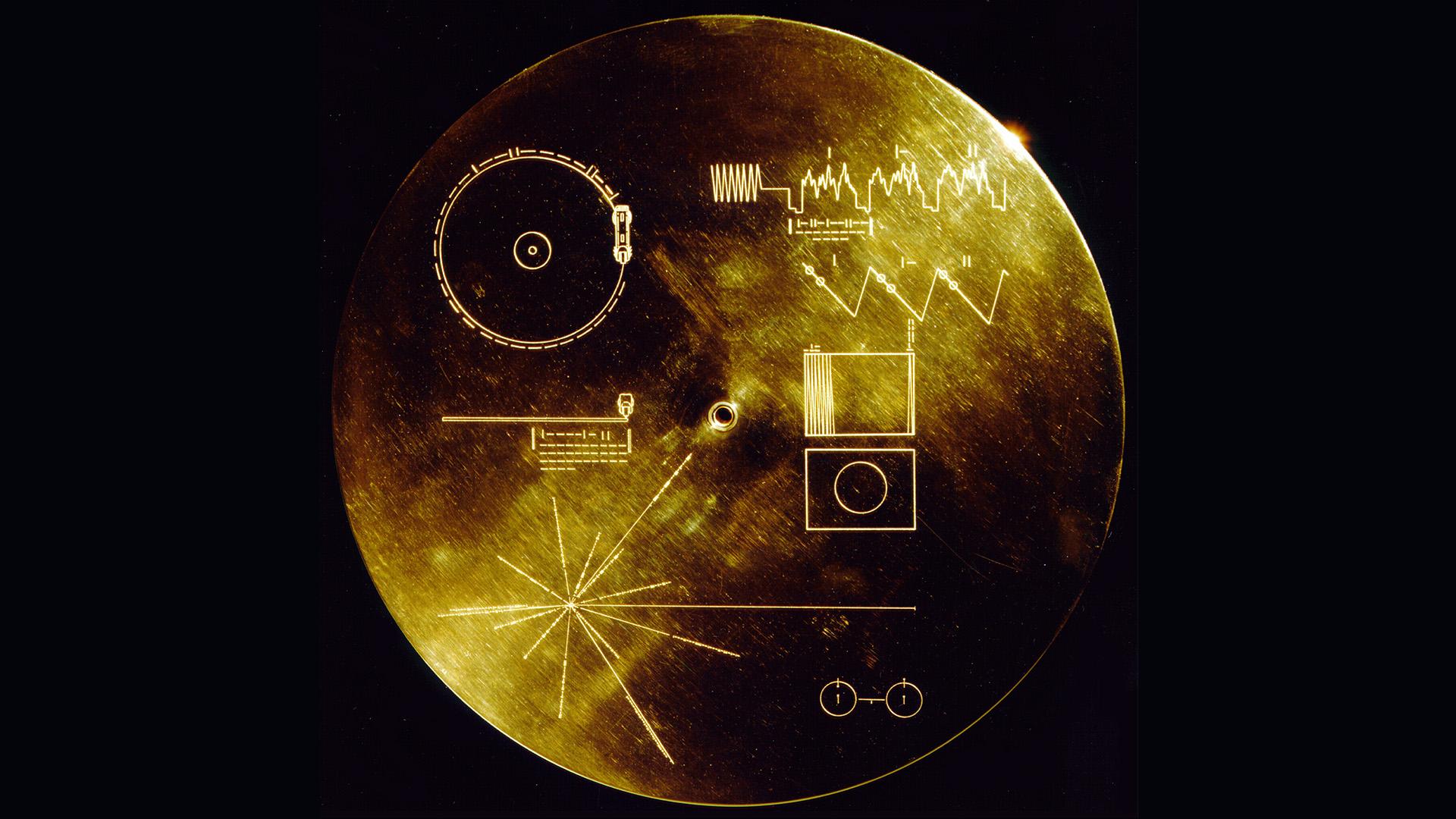

You ask about the paint, I said. I cannot go on record speaking about the paint, but I will say this about it: such a red paint: were one to imagine how such a paint might be obtained, one would think thusly:

a thief would have to be employed to sneak into cathedrals all throughout Europe and take the long preserved relics of 16 or 17 saints. Those relics would have to be brought to a secret place and ground up along with the rusted metal of a train wheel that had crushed a man. Then the mixture must be laid out on a thin pan for years on a rainless mountain peak where now and again a sovereign lidded cloud passes over failing ever to look down.

If there were such a red color as this, I said, it is in such a way that it might be made. We take no responsibility for the regrettable thefts that have been reported now these many years, and we are sorry to hear that the great cathedrals of Italy have scarcely a relic left to rub between them. Nonetheless, I offer to you this fine red bird. You say you will pay with a check?

I wrapped the bird in a fine white cloth and then in another of thicker silk and then another of wool and finally a coarse canvas.

That was the sale of the red bird.