Little White Overcoats

James Baldwin and writerly trust

by Robert Reid-Pharr

IN September of 1974, Abel Meeropol—still reeling from the sense of defeat and despair following the close of the “hot” part of the US Civil Rights movement and the assassinations of Martin King, Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X—wrote to his remarkable former student, the activist and literary genius James Baldwin. “I have been wanting to write to you for many, many years and since I am very, very much older than you, I had better do so before I cease to exist,” Meeropol began.

I taught for eighteen years at DeWitt Clinton High School and I believe you were in my first or second term English class. It is impossible to remember names at my age, but I do recall vividly incidents in the past and the individual involved. I remember a small boy with big eyes and the circumstances which impressed me so much. I made it a practice to send groups of boys to the blackboard to write one paragraph on a particular subject and then have a general discussion with the class as to how well each boy expressed his thoughts and feelings in the paragraph. The subject I suggested to the boys for the paragraph was to describe some aspect of a scene of nature. You chose a winter scene in the country and the one phrase I never forgot was “the houses in their little white overcoats.” It was a beautifully imaginative expression from a little boy.1

Abel Meeropol, sentimental and aging, could not have written a more perfect, indeed more eloquent paragraph. Baldwin’s person, small bodied and big eyed, confident and imaginative, is presented with a delicacy that thumps the heart and nips the breath. One can hardly believe that these effortless and kind words could come from a man whose life was so brutally punctuated by the realities of the country’s ever-more-clipped retreat to right-wing hysteria.

Immediately after his paean to the young Baldwin, Meeropol reveals a basic truth about himself and his family that had necessarily been kept private and discrete, if not exactly secret, for many years.

My sons, Michael and Robert, were the Rosenberg children born to Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. My wife, Anne, knew that at some point in their lives, as well as I did, that Michael and Robert as adults would shed their anonymity, which was essential when they were young, and that they would expose the frame-up of their parents. My wife, Anne, died on September 13, 1973. I am glad she lived long enough to see Mike and Robby fight to clear the names of their parents. We were both so proud of the boys. (Abel Meeropol to James Baldwin, September 5, 1974, n.p.)

Here one dreams a dispassionate Baldwin snapped into quick attention by the slow motion spectacle of his former teacher’s disrobing. The trial and June 19, 1953 execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, convicted of helping to pass American nuclear expertise to the Soviet Union during the Second World War, was a singularly disastrous moment for the American Left, one recognized as the bellwether of the increasingly vicious attacks on progressive activists and intellectuals during the 1950s and beyond. The particularly weak case against Ethel Rosenberg was especially galling to progressive Americans who were outraged that this 37-yearold mother of two boys, six and ten years old, had seemingly been put to death largely as retribution for her radical politics. The fact that her execution was so gruesomely violent—a total of five electric shocks given until she lay dead, smoke rising from the char of her flesh—was and is a none too-subtle reminder to progressive Americans of what the consequences of radical dissent can be.

Even as this surprising revelation undoubtedly left Baldwin stunned, perhaps reeling, Meeropol had at least one more darkly iridescent object in his bag of rare tricks. Like the Harlem Renaissance writers Countee Cullen and Jessie Fauset, who taught at Baldwin’s junior high school and high school respectively, Meeropol had been an artist teaching his craft in the New York public schools but always looking outward toward the possibility of a larger, grander, and more public creative life. Years before leaving DeWitt Clinton, in 1945, Meeropol had already attained quite significant success. Writing under the pseudonym Lewis Allan—itself a mark of unfinished mourning, as “Lewis” and “Allan” were the intended names of Meeropol’s two stillborn sons—he established himself as a quite successful poet, lyricist, and songwriter, creating works performed by Frank Sinatra, Billie Holiday, Peggy Lee, and Nina Simone, among many others. In particular, he wrote the anti-lynching dirge “Strange Fruit,” made famous in 1939 when Billie Holiday’s plaintive performance of the piece was released as a single by Commodore Records, with her rendition of the jazz standard “Fine and Mellow” on the flip side.

It is astonishing to consider that during 15-year-old Baldwin’s sophomore year at DeWitt Clinton, one of his teachers, whom he would later barely remember, secretly published a song that would become not only an anthem of the anti-lynching, anti-white-supremacist movement, but also an emblem of the refusal of conscious and progressive individuals in the US and elsewhere to turn away from or ignore the systematic ritual killings of African Americans.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the Poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of Magnolia sweet and fresh,

And the sudden smell of burning flesh!

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for a tree to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

Baldwin would quickly register his own shock about how impossibly complicated the social, political, and intellectual situation was at DeWitt Clinton during his time there. Writing to Abel Meeropol on September 29, 1974, he admitted that he had no idea of the profundity of his teacher’s involvement in Left American culture nor how much that involvement had cost him and his family. “It never occurred to me, of course, that one of my teachers wrote ‘Strange Fruit’—though that also seems, in retrospect, unanswerably logical,” he remarked. “Nor could it possibly have occurred to me that one of my teachers raised the Rosenberg children. It’s a perfectly senseless thing to say, but I’ll say it anyway: it makes me very proud.” 2

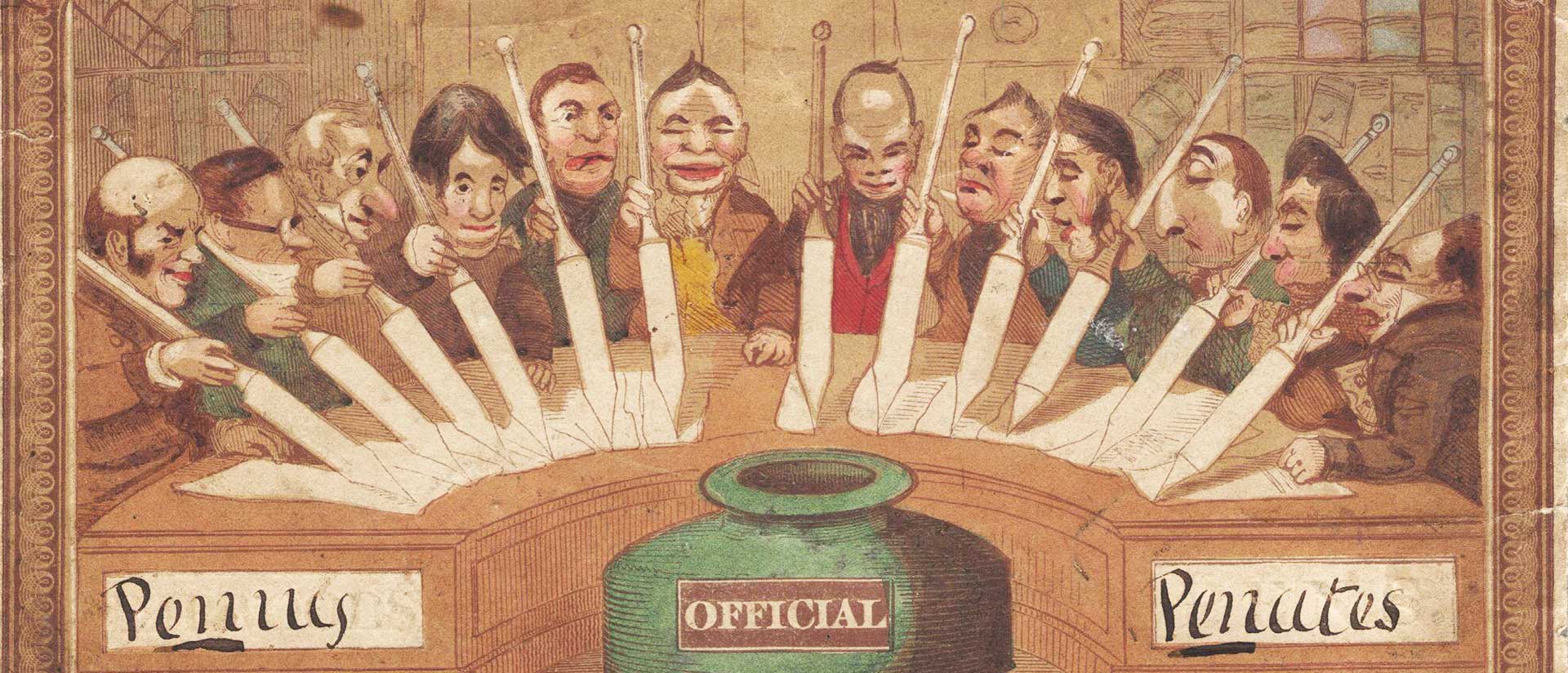

I WANT to focus at this juncture less on the matter of the vagaries of human connection, the ways in which none of us can ever be certain of how the actions of our neighbors and colleagues will impact our lives, and instead on pedagogical practice, the teaching of not only writing but also the ability to look, to see, and to transmit what one finds to a not-yet-formed audience, that clumsy entity composed of equal parts promise and menace standing just beyond the margins of the imagination. “Get up! Go the board! Write something! Write it handsomely! Be succinct! Be quick! Take criticism! Return to your seat! Repeat! Do not stop!” Abel Meeropol, committed communist dialectician that he was, focused with his students less on content and style than on form and process. Though the lovely phrase “the houses in their little white overcoats” charmed his teacher, Baldwin recalled nothing of that moment. Instead, his focus remained bluntly on the structure and stability Meeropol provided. “I don’t remember what you remember,” he wrote. “I remember only the blackboard and the bottomless terror in which I lived in those days—but if I wrote the line which you remember, then I must have trusted you.”

Here we see clearly the logic of any effective creative practice. The forms we are taught, the stiff rules of grammar, syntax, tone, and diction the competent writer must learn and re-learn, must allow himself to be captured by if he is to achieve anything approaching “voice,” are necessarily secondary to the promise of connection that our handiwork, however inadequate or clumsy, is designed to achieve. The act of writing is, first and foremost, an act of trust. It is a demonstration of the willingness to yoke the languages and sensibilities of one’s forebears to the stiff, exacting protocols of formal practice. And if we are lucky and stubborn enough, we might break through the worlds of difference that separate us to show the everyday, human-scale grandeur of our naked faces. Each time we draw pen across paper, chalk across board, a prayer is released. For a moment, we are confronted by a basic, vital, and uncomplicated truth. For those of us who run, for those who leave behind the comfort of the familiar, for those with strong backs and empty hands, our faces turned toward the promise of an ill-defined future, our tender hearts beating valiantly beneath damaged bone and thin winter coats, there can be no rest. Travelers all, we can never stop.

I should pause for a moment to admit that I am surprised—perplexed, in fact—by the reality that an individual with the remarkable talents and the no-nonsense erudition of James Baldwin actually had so little formal education, indeed just 12 brief years. I have shown already that part of the reason he ended his schooling so well prepared was that from his first days in the New York public school system, gifted educators recognized the uniqueness of his intellect, then actively—indeed courageously—worked to cultivate it. Frankly, it should come as no surprise that Baldwin seems barely to have even considered attending university, not bothering to attempt admission to either the City College of New York or Columbia, both of which were in walking distance of his home. Young, black, extremely poor individuals from families supporting nine children are highly unlikely to gain access to the American higher-education system in the early years of the twenty-first century. We should not be surprised then that this fact was doubly true in the first half of the twentieth.

What inspires me, however, what massages the bleeding heart, is the commitment, the conspiracy, really, of a host of individuals to make do with the scant resources that they had available to them in order to snatch some bit of dignity and promise from the teeth of institutions designed to corral our bodies, dull our intellects, and blunt our spirits. These teachers knew that boys like James could never expect to extend their formal training beyond the sometimes exceptional opportunities afforded them in Harlem and the Bronx. In the face of that reality, they taught the boy to extract beauty and vigor from the resources at hand. And in doing so, they let him know that even though he might never be welcomed in Cambridge, New Haven, Berkeley, Berlin, Oxford, or Paris, at least not through the front gates, he still might seek something approaching safety and solace in the “houses in their little white overcoats.” He might take the lessons learned in his youth, massage them, bend them, discard what was worthless, hold tight to what was useful, and then turn his face in the direction of the great, aloof, always-promising world and begin again. □

1) Abel Meeropol to James Baldwin, September 5, 1974, James Baldwin Papers, 1936 – 1992, Sc MG 936, Box 3B, Folder 2, n.p., Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

2) James Baldwin to Abel Meeropol, September 29, 1974, James Baldwin Papers, 1936 – 1992, Sc MG 936, Box 3B, Folder 2, n.p., Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.