Earth’s Greatest Hits

Do aliens like human music?

by Alexander Rehding

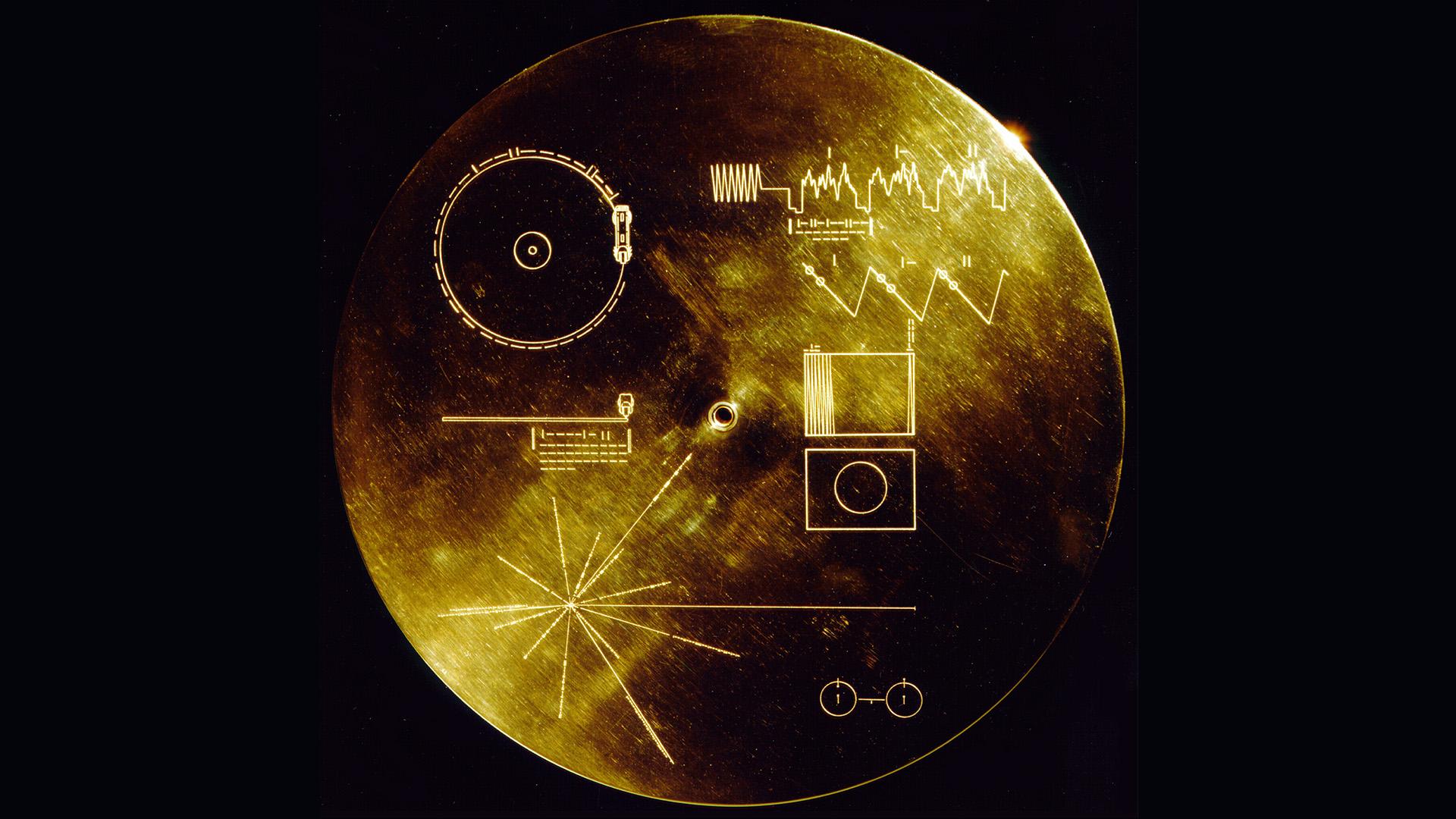

In 1977, NASA shot a mixtape into outer space. Technically, it wasn’t a cassette tape so much as two LP records, gilded for protection against the extreme conditions of outer space, and each mounted to the outside of a space- craft, Voyagers I and II. But other than that, these so-called Golden Records were very much mixtapes in the spirit of the 1970s, carrying a special musical message for a significant other. This interplanetary playlist contains music from all parts of our world and in all styles, from Australian didgeridoos to Zairean initiation songs, from J.S. Bach to Chuck Berry. Traveling at some 35,000 mph in the direc- tion of two of the nearest star systems, the Voyagers and their Golden Records left our solar system in 2012 and 2018. They are now on their way into the unknown, barreling into areas of our galaxy where no human-made object has ever ventured before.

Conceived at the height of the Cold War, the Golden Record was an ambitious effort to represent the entire planet in sounds. Etched into the two sides of the LP were music and noises that would give aliens a sense of what it means to be human. It was especially important for the creative team that the telegenic astrophysicist Carl Sagan (1934– 1996) had assembled around this project to highlight that this compilation encompassed not only America but the whole planet. The 27 musical numbers on the Golden Record include a diverse mix of pieces chosen from the Western classical canon, African American blues, as well as a great many popular and high-art traditions from other parts of the world. The Soviet Union is delicately represented with two contributions: Azerbaijani mugam and Georgian choral singing. The creative team was hoping to include the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun,” but NASA could not secure the copyright from EMI in time. Besides musical traditions from all habitable continents, the Golden Record contained greetings in 55 languages, including whale song, a sound collage of Earth noises, and over a hundred sonified images depicting scenes from our planet and its inhabitants. Any hints of war, conflict, and suffering were carefully omitted. After all, we want to present ourselves from our best side.

Why music? Three distinct theories, or rather vernacular philosophies, are at work behind the Golden Record. First is the age-old connection between music and mathematics going back to Pythagoreanism, overlaid with the Romantic trope of music as the universal language, and third, the mixtape concept that music gives away something deep and personal about our identity, individual or collective. An additional attraction of the auditory dimension is related to its predecessor, NASA’s Pioneer mission (1972). An iconic plaque was mounted on that spacecraft on which is seen, among other things, a line drawing of naked man raising his hand in greeting, with a naked women standing beside him. Anatomically accurate, the nudity depicted in this plaque caused a firestorm in conservative religious circles. Because NASA relies on taxpayer money apportioned by Congress, they decided to steer away from controversy and moved away from visual images toward sonic representation.

The golden record is a tool in the attempt to answer a well- honed existential question: Are we alone in the universe? In the last few years, astrophysicists have confirmed the existence of several thousand exoplanets and estimate a further one hundred billion exoplanets in our galaxy. From a purely statistical perspective, then, it is highly likely that life, even intelligent life, exists on other planets. The Golden Record is, after all, the brainchild of Seti, a group of star-studded scientists dedicated to the Study of Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence. However, the hope that an alien civilization would somehow pick up our Golden Record had always been a pipe dream. Sagan knew well that the Voyager spacecraft were merely two shots in the dark. Human culture, he reckoned, was still a “baby civilization,” far away from reaching its full potential to communicate. Records piggy-backing on spacecraft is about the best we could do.

The golden record is a tool in the attempt to answer a well- honed existential question: Are we alone in the universe?

To be sure, none of us will be around to find out whether the Golden Record will reach anyone at the other end. Even at the unimaginable speed at which the Voyagers travel, it will take them at least 40,000 years to be closer to the nearest stars than our own sun.

The odds are wildly stacked against successful contact. Even if an intelligent alien species were at the right place at the right time to intercept a Voyager on its trajectory, their physiology would have to be reasonably similar to human anatomy—with visual organs to decipher the wordless instructions, an auditory sense to listen to the music, hand- like extremities to handle the record, and the technological know-how to build a record player. We won’t even go into the more complicated aspects of listening to music, such as a feeling for rhythm and phrase, or the capacity to form an emotional response to different musical styles. The likelihood that all these factors come together is not quite zero, but very close to it. For a thought experiment, take a non- human intelligent species on our planet: whales. Floating in their watery medium, their fins would not be able to hold the record, let alone take any of the other necessary steps.

In the end, though, none of this matters much, because the Golden Record was primarily created to inspire a domestic, Earth-bound, human audience. And in this regard it was wholly successful. The Golden Record stood so much in the limelight that it outshone the considerable scientific aspects of the Voyager mission, which gave us the first high-quality photographs of the gaseous outer planets of our solar system.

Not everybody was satisfied with the majestic— and perhaps a little cheesy—Golden Record. A few years later, in 2001, Aleksandr Zaitsev (1945– 2021), a Russian astrophysicist, came up with a rather different approach to communicating with extraterrestrial civilizations through the power of music. Zaitsev was a vocal proponent of a more active approach to Seti and seemed particularly bothered by the relatively slow speed and limited success rate of the Voyager project. He chose to pursue an alternative route.

Seti builds on a problem known as the Fermi Paradox, which can be summarized as follows: If the universe is teeming with life, where is everybody? Why has no alien civilization ever made contact with us? There are various plausible answers to this paradox, including the humbling thought that our species might simply not be interesting enough. One important consideration is Sagan’s “baby civilization” idea: humans have only had the capacity to receive radio messages for a few decades, which in astronomical terms is nothing. Seti aims to determine the conditions of alien intelligent life. These are, in fact, more limited than one might expect: a few fundamental assumptions can reasonably be generalized, such as alien life forms are likely carbon-based and that they most probably exist in a fluid (gaseous or liquid) medium. And Sagan and his colleagues were convinced that mathematics, as the language of science, would provide the basis for any interplanetary, inter- species communication. At its loftiest level, Seti aims to determine the optimum conditions in which humans can receive and send messages to engage in communication with alien civilizations.

If the universe is teeming with life, where is everybody? Why has no alien civilization ever made contact with us? There are various plausible answers to this paradox, including the humbling thought that our species might simply not be interesting enough.

This aspiration to make contact had always been controversial. The physicist Stephen Hawking (1942–2018) thought it was dangerous folly to send messages to outer space. Without first knowing whether anyone out there would be hostile or friendly, Seti might unwittingly bring doom to our whole planet. Meanwhile, Meti (Messaging Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence), a movement spearheaded by Zaitsev, swept such hypothetical concerns aside and argued that if every civilization in the galaxy is too timid to take the first step in making contact, then we will never find each other.

Zaitsev put his money where his mouth was and organized a concert for aliens, or as he called it “TAM for ETI”— Teen-Age Message for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence. He first approached the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico with his idea, but it was turned down because of security concerns. (This, despite the fact that several widely publicized messages into space had previously been sent from Arecibo.) The concert finally took place at the radio telescope at Yevpatoria, in Crimea. Over a week at the height of the summer of 2001, Zaitsev, with the help of a youth group from Moscow and financial backing from the Russian ministry of education, organized a series of concerts for theremin— an iconic electronic instrument patented in 1928 by Russian engineer Lev Termen (Leon Theremin, 1896–1993) that emits wobbly tones easily recognized as the “sound of outer space” in countless science- fiction movies—that were broadcast in different directions within of our galaxy.

Zaitsev focused on a small repertory of Western (and specifically Russian) classics— including such hits as Beethoven’s Ode to Joy, Saint-Saëns’ Swan, Rachmaninov’s Vocalise, and the folk song “Kalinka.” These tunes had the benefit of being well-suited to the theremin, but better yet, the sound the traditional theremin emits is a simple sine wave, which rarely occurs in nature. This mode of transmission makes it easy to separate signal from noise. Intelligent aliens, we can assume, will likely understand that these are not random waves, but a deliberate message.

Zaitsev focused on a small repertory of Western (and specifically Russian) classics— including such hits as Beethoven’s Ode to Joy, Saint-Saëns’ Swan, Rachmaninov’s Vocalise, and the folk song “Kalinka.”

NASA’s Golden Record selection had stressed the worldwide diversity of musical styles, genres, and provenances. It aimed to strike a delicate balance during politically unstable times. Zaitsev’s project, by contrast, was closely circumscribed: its musical selection hewed closely to the Western canon, and its presentation completely gave up on any kind of timbral variety. But the virtue of such frugality was a highly specific, recognizable signal that conveys unmistakably, “We are here.” Most importantly to Zaitsev, these “concerts”—or, really, radio transmissions—are not bound to a physical object like the Golden Record. That is, they are not held back by the relatively slow speed that rocket fuel provides. The concerts travel through space at the speed of radio waves and will arrive at near star systems in a matter of years, not millennia.

The first of these transmissions may arrive at their target star, within the Ursa Major constellation, as early as 2047. Will aliens like human mu- sic, played on the theremin? Maybe, just maybe, we will find out by the end of this century.

Photo: The Golden Record cover shown with its extraterrestrial instructions. Credits: NASA/JPL