How to Have Sex in a Pandemic

by Juana María Rodríguez

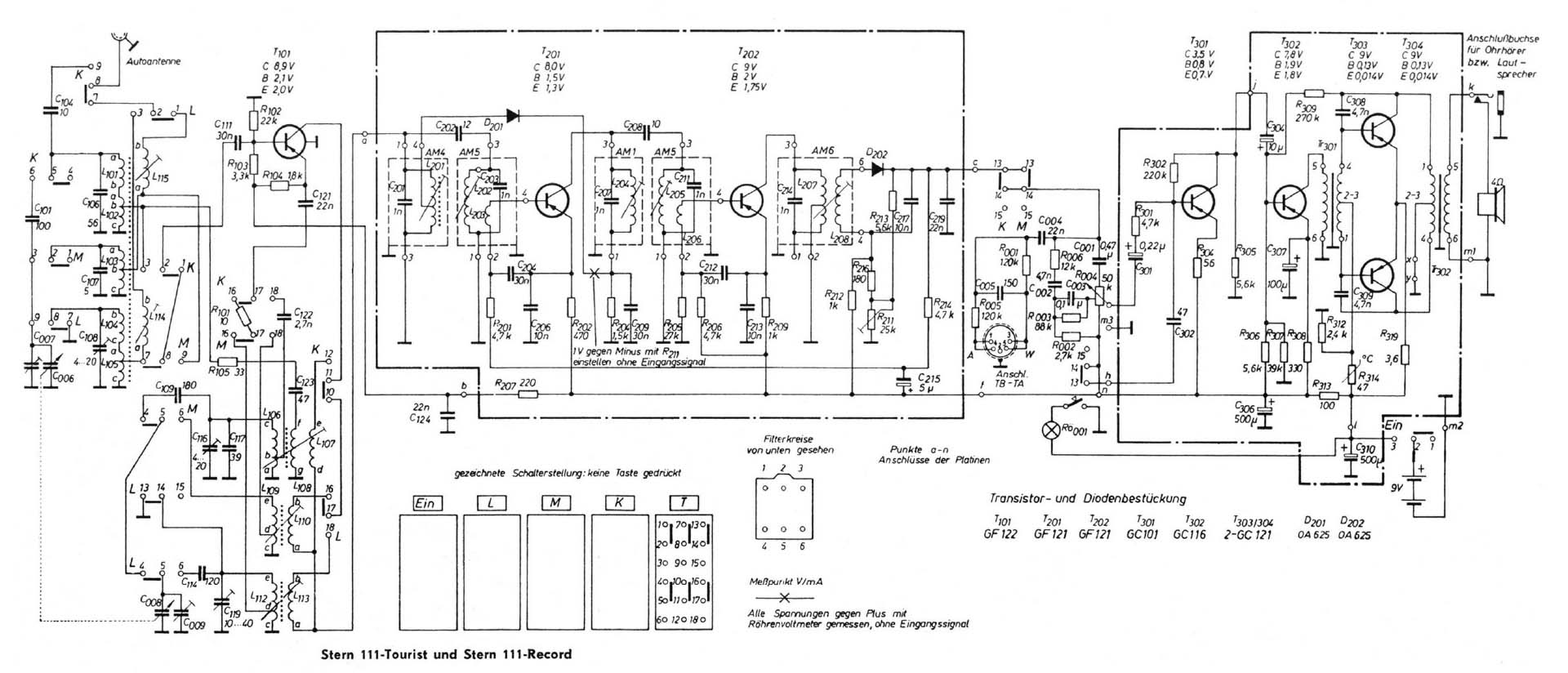

Throughout early 2020, as the uncertainty, anxiety, and fear surrounding COVID started to take hold, many of us began to think back on that other pandemic that similarly warned us to keep our distance, steer clear of strangers, and be willing to sacrifice pleasure for safety. In 1983, when AIDS was still being referred to as the “gay plague,” Richard Berkowitz, an S/M hustler, and Michael Callen, an HIV-positive musician, worked with their virologist, Richard Sonnabend, to publish How to Have Sex in an Epidemic. At a moment when public health officials (and some gay-community members) were railing against the dangers of gay promiscuity, that text delivered a retort to the state neglect and local terror gripping the queer community to offer a model of what community care might look like. They subtitled it “One Approach,” because, even then, it was clear there is always more than one approach to dealing with unimaginable tragedy.

Despite some shaky science, that self-published booklet became the first “safe-sex” guide that promoted the use of condoms and served as a collective refusal of public-health demands to abandon the radical pleasures of queer sex. Instead, that booklet, and the many other safer-sex guides that would follow, ushered in an era and ethos in which we got better at communicating limits, risks, and the carnal particularities of our erotic desires.

Fast-forward to 2020: California wildfires are raging and a global pandemic is slowly shutting down the world as we know it, exposing all of the inequities of global hierarchies predicated on unequal access to resources and care. And, to add to the catastrophe gripping the world, I am single.

Being uncoupled, like being coupled, or being in a poly-pod is one of the things that has defined the conditions for how we are surviving the COVID crisis. Just like those early days of the AIDS pandemic, COVID has produced a moment where moral judgement shrouds the decisions we might make about our corporeal autonomy. As they had during the AIDS crisis, the categories of race, class, gender, ability, and citizenship, as well as the details that define the social conditions of our lives, influence rates of survival and shape the public scrutiny and judgment that surrounds infection. As usual, sex provides the flashpoint for social anxieties around morality. Polite society would have us believe that sex is both individual and private, where privacy is a luxury few outside socially sanctioned forms of domesticity are ever afforded. That is to say, for people who live under constant state surveillance—prisoners, immigrants, the unhoused, sex workers, and others deemed perpetually suspect—sex is continually being defined, regulated, and controlled by laws and public policy intent on wiping clean the soiled surfaces of public life. Now as then, some of us are simply unwilling to abandon the dirty pleasures that sexual touch promises for the hollow assurance of social respectability.

Polite society would have us believe that sex is both individual and private, where privacy is a luxury few outside socially sanctioned forms of domesticity are ever afforded.

Not everyone needs or values sex in the same way. During the COVID lockdown, coupled people in cozy domestic arrangements—those who had followed the proper rules of social reproduction—could just continue to have (or not have) the same sex they had been having before. Meanwhile, the rest of us were just expected to cross our legs and wait it out. For me, with the world on the brink of collapse, giving up on the possibility of a sexual future seemed too unimaginable and depressing; just living was hard enough and, after several months into the pandemic, celibacy was getting old fast. In May of 2020, I read how the Dutch Government had begun advising single people seeking intimacy to find a “sex buddy” to ride out the pandemic. It seemed like the sort of reasonable advice we would never receive from public health officials in the United States. And so, with the possibility of nightclubs, travel, museums, and in-person flirting far off in the distance, I decided to go online to seek out a Pandemic Lover.

Like a lot of single people and many coupled ones, I have dating profiles on various apps. While some, like Tinder, are more associated with casual encounters and tend to attract younger people, I favor those other apps, born of the cruel optimism that defines modern dating, that cater to humans looking for love and relationships, even when that is not exactly what I’m seeking. But securing a suitable Pandemic Lover seemed to require extra layers of courtesy and communication less frequently conveyed on platforms designed for fleeting sexual hookups.

Very soon I found myself chatting with a very handsome Latino trans-man with bedroom eyes who had indicated on the generally tame dating site OkCupid that his favorite thing to do on a first date was shag. I had tried unsuccessfully to find romantic connection on the apps, but this was different. I wasn’t looking for a long-term committed relationship just so I could have a steady sex-partner; I was in the process of trying to negotiate my first sexual escapade with a stranger in years, during a global pandemic, and there were details to be discussed. What was his level of public contact? What did he do for work? Who did he live with? Who were his other sexual partners? Had he been tested, and when?

I wasn’t looking for a long-term committed relationship just so I could have a steady sex-partner; I was in the process of trying to negotiate my first sexual escapade with a stranger in years, during a global pandemic, and there were details to be discussed.

If you have spent any time on these apps, you know getting from text to flesh can take a minute. In this case, the task was to get the details necessary to make an informed decision about COVID exposure, check in with my gut about how much to trust this stranger who was about twice my physical size, arrange the logistics of where and when, discuss erotic limits and desires, all while trying to keep the vibe sufficiently light, sexy, and fun, against a California backdrop of orange smoke and the ’Rona.

Luckily, as kinky queers versed in the lessons of the AIDS pandemic, we both knew how to use our words. But the particulars of risk are worth mentioning, because they tell us something about sex and vulnerability, pleasure and risk. Almost immediately in the conversation, he indicated that he, like me, is bisexual. He told me the current extent of his sexual life consisted of a long-distance romantic partner and a long-standing non-romantic local hookup, both cis-men. He is in his mid-forties and lives with a female ex-lover in her sixties who is retired and doesn’t leave the house much. He is a working-class guy who has a day job that requires minimal contact. In my mind, I was already coding these details of race, class, age, and sexual practices in relation to risk factors, both real and imagined.

Bisexuals are always imagined as somehow more promiscuous and therefore riskier as sexual partners. During the height of the AIDS pandemic, bisexuals of all genders were deemed disease carriers who brought HIV to unsuspecting lesbians and heterosexual women. Yet his claiming bisexuality from the start seemed like a good measure of his trustworthiness in a moment when many people just call themselves queer and skip the details about who or what they do sexually. Other than his roommate (because few people in the Bay Area can afford to live alone), he had one other carnal lover, an administrator in the health care industry. Meaning: regular testing even in the absence of exposure to others. On the other hand, I live with my eighteen-year old son, who splits his time between three households—my own, his other parent’s, and his girlfriend’s. He also works construction with a work crew made up of mostly undocumented Latino men, most of whom live with extended families. The truth is, even with precautions, my son was much more of a potential transmission vector than anything in Pandemic Lover’s circumstance. Yet, I was also keenly aware that any social judgement surrounding my willingness to hug my son would no doubt be viewed quite differently than my decision to have sex with a stranger.

Bisexuals are always imagined as somehow more promiscuous and therefore riskier as sexual partners.

When my date arrived around midnight and I opened the door, maskless, to invite him in, I had a panicked flash of the risk I was about to take. Even after exchanging erotic proclivities and exposure factors, both of us were as uncertain about the potential dangers as we were about the imagined possibilities for pleasure. COVID is not like HIV; it is not as easily preventable and much more unpredictable and uncertain in terms of its impact. The first time we had sex, we didn’t kiss. But soon we did, and we still do. That COVID is life-threatening made my desire for the life-affirming vitality of sexual touch feel all the more urgent, a risk worth taking.

I should add that even though we are both vaccinated now, with other options for satisfying our sexual urges, we still see each other. And although this became much more than a hook-up, it is still not about amorous union, monogamy, or happily ever after. Instead it is about the joy and intimacy that comes from sharing fragile bodies in a precarious present, and the promise of mutual care that can thrive when risk and vulnerability are held together. And maybe that is precisely the kind of care work that sexual contact can aspire to be, the kind of trust and honesty that makes it possible to have our desires, limits, and needs held tenderly.

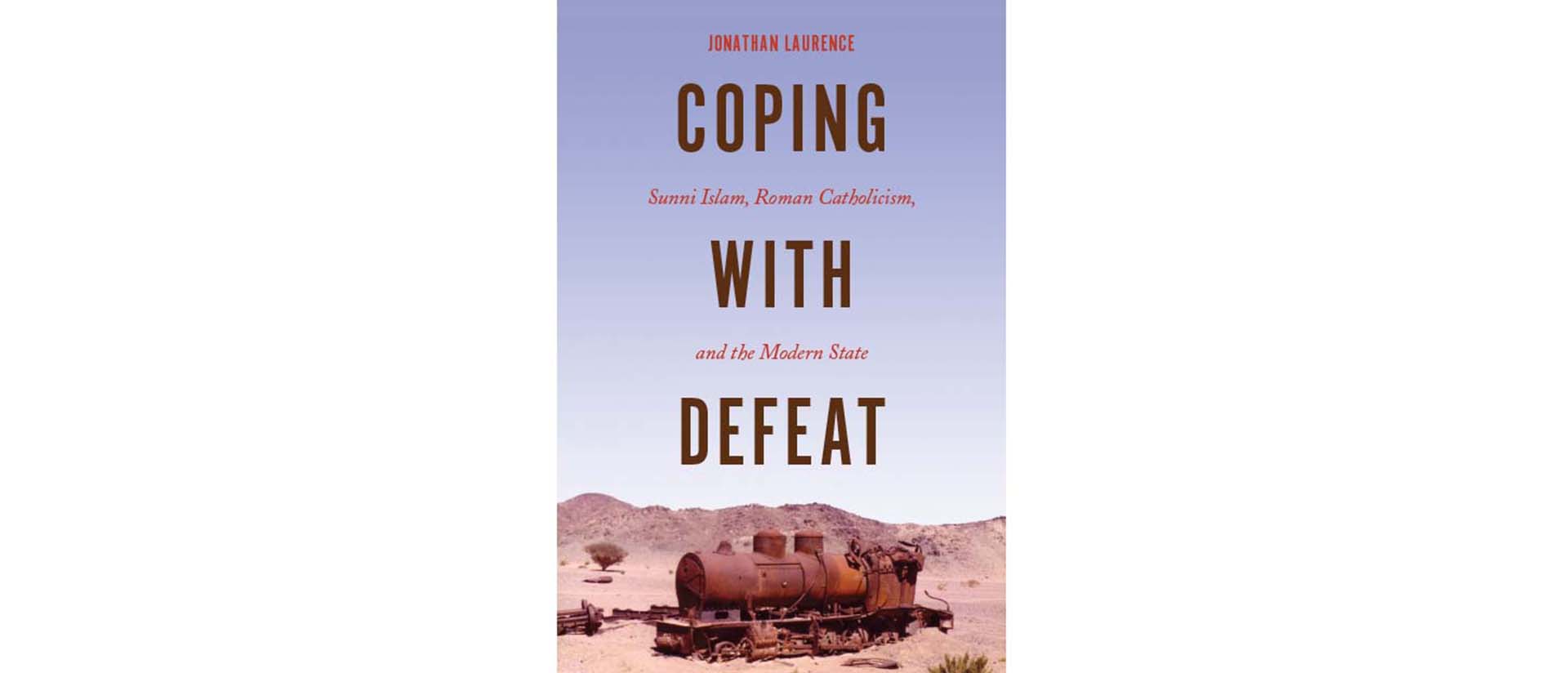

This pandemic has shed light on the kinds of durable and fleeting intimacies capable of sustaining us, and our role in actively nurturing the social networks of our lives. How do we show up for each other to imagine what survival might look like in a moment of state abandonment? Who are we helping with childcare, eldercare, access needs, rent? Who are we helping survive a break-up or survive eviction? And who are we turning to with our own anxieties and fears? Like AIDS, the COVID pandemic has inspired communities neglected or policed by the state to offer their own models of community sustenance and support. And for many of us, that includes thinking about access to sex, not as an individual right but as a form of mutual aid that can function as an exchange of intimate care. Because those of us who live outside of the shelter of the socially recognized bonds of family and normative domesticity might also find we need love, touch, connection, and intimacy—even if it does not resemble the imagined romantic, sexual, intellectual, and spiritual union of normatively coupled life.

Like AIDS, the COVID pandemic has inspired communities neglected or policed by the state to offer their own models of community sustenance and support.

Being someone’s singular special someone is always imagined as that thing that you cannot not want. Yet, for me, the pandemic has created another kind of appreciation for the plurality of the intellectual, material, spiritual, and sexual bonds that have sustained me as a single person— my daily writing partners, the friends with whom I routinely share meals, gossip, make emergency evacuation plans and plan protests, and the virtual playgrounds where so many new social bonds are formed and fed. And to this mix of self-care and political survival, I can now add regular sexual touch that also feels like a growing bond of friendship, joy, and cariño. As we ready ourselves for the next crisis sure to arrive, these queer practices of world-making are precisely the lessons we will all need to survive.

This essay emerged from a panel presentation organized by Chandan Reddy and Gayatri Gopinath, “How to Have Sex in a Pandemic: Intimacy, Disease, and the Politics of Vulnerability.” Special thanks to co-presenters Dean Spade, Amber Musser, and Kenyon Farrow for their insights and comments.