Mobilizing Fear

Propagandizing German–Ottoman conflict

By Carina L. Johnson

At the end of the twentieth century, German public discussion about Turkey focused on its relationship to Europe. This topic lay at the heart of two complex political and social questions: first, what should become of the Turkish guest workers and their families who had been living in central Europe for decades or, in the case of their children, for their entire lives? Second, should Turkey be welcomed into the European Union? Each debate raised deeper questions about the legacies of Europe’s Christian past, of citizenship rights determined by descent, and of cultural plurality in German and Austrian society. Voices for and against Turkish integration drew on the lessons of history to support their positions.

Today, critiques of Turkish integration have become ever more entangled with anti-Islamic rhetoric in the wake of terrorist attacks, proclamations of Europe’s essential Christian identity by prominent figures, and the crisis of refugees fleeing violent conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria. Although Germany did create a path to citizenship by birthright in 1999, the public controversy surrounding soccer player Mesut Özil’s resignation from the German national team, in July 2018, highlights how fraught German identity continues to be for people of Turkish descent. And Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s shift away from earlier pro-democracy policies has only encouraged some opponents of Turkey’s membership in the EU to continue defining Turks as unassimilable because they are Muslims.

European and US press and academics increasingly refer to this repudiative rhetoric as part of a broader Islamophobia, also applied to Arab and South Asian Muslims. Such an encompassing approach facilitates a Europe-wide view, and anti-Turkish and anti-Islamic rhetoric are undeniably entangled. Yet while Islamophobia is deployed in the public sphere for political ends, the very term identifies a religion, Islam, rather than a racialized group or ethnicity as the locus of fear and concern. Efforts to subsume the “Turkish question” within discussions of the place of Islam in Europe ignore a long history of the Ottoman polyreligious state by presuming that all Turks are and have always been Muslim. An examination of anti- and pro-Turkish rhetoric reveals its non-Islam focus. It has, instead, been directed toward a people and polity—first the Ottoman Empire and then its largest successor state, Turkey.

The past has often been invoked in contemporary anti-Turkish rhetoric, implicitly proposing that the cultural memory of longstanding German–Ottoman conflict and antipathy justifies a position of exclusionary gatekeeping. This, however, is a selective recollection of the past. At the beginning of the twentieth century, for example, the new nation state of Turkey was the object of admiration, of Turcophilia. For German observers struggling to forge new states after the collapse of their own German and Austro-Hungarian empires, Turkey was heralded as a triumph of secular modernization, offering a model for a new German nation state. Rather than revealing centuries of unremitting antipathy, the history of German Turcophobia illustrates the extent to which the “fear of the Turk” has been selectively mobilized across history in the service of political aims. It is no accident that in the history of German sentiments about “the Turk”—whether a metaphor for the subjects of the Ottoman state or a reference to their ruler—the episodes of Turkish aggression are the best known.

The milestone military conflicts that have been deployed for political purposes include the conquest of Constantinople and the fall of the Byzantine Empire (1453), the first Siege of Vienna (1529), the Long War (1593-1606), and the second Siege of Vienna (1683). Some of these uses were successful, some less so, but the events and their politicized memories continue to be invoked in the present day.

The first of these instances was Sultan Mehmed II’s conquest of the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, in 1453. The papacy reacted by redoubling its efforts to galvanize Latin Christendom into a military response. These calls for a new crusade were largely ignored. Imperial officials also sought support for a large-scale armed response to the expanding Ottoman Empire. Holy Roman Emperors Friedrich III and Maximilian I had some success mobilizing Austrian and Tyrolian troops to fight in Hungary, in the continuation of their ongoing dynastic conflicts with the Hungarian crown and in response to Turkish raids in eastern Austrian lands. Yet repeated appeals to the imperial estates were met with little enthusiasm.

In the 1520s, under Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and his brother, Ferdinand, German lands remained unresponsive to Habsburg and Hungarian warnings about the Turkish threat, even after Louis II of Hungary was killed, in the 1526 Battle of Mohács, between Ottoman and Hungarian forces. Only with the Siege of Vienna in October 1529 did the Turkish threat became tangible to many in the Holy Roman Empire. News of the siege was sent out in an urgent appeal for help, carrying with it stories of violence and destruction wreaked by the Ottoman army as it marched up the Danube. In response, cities and princes ceased delaying and rushed to send troops to liberate Vienna. With winter coming, the Ottoman army departed Austria in November, but many in the Holy Roman Empire expected a repeat offensive in the near future. During the next two years, the Habsburgs worked to negotiate an agreement with the newly Protestant estates: a guaranteed, limited-time toleration of evangelically reformed worship in exchange for contributions of money, materiel, and manpower for the Turkish wars.

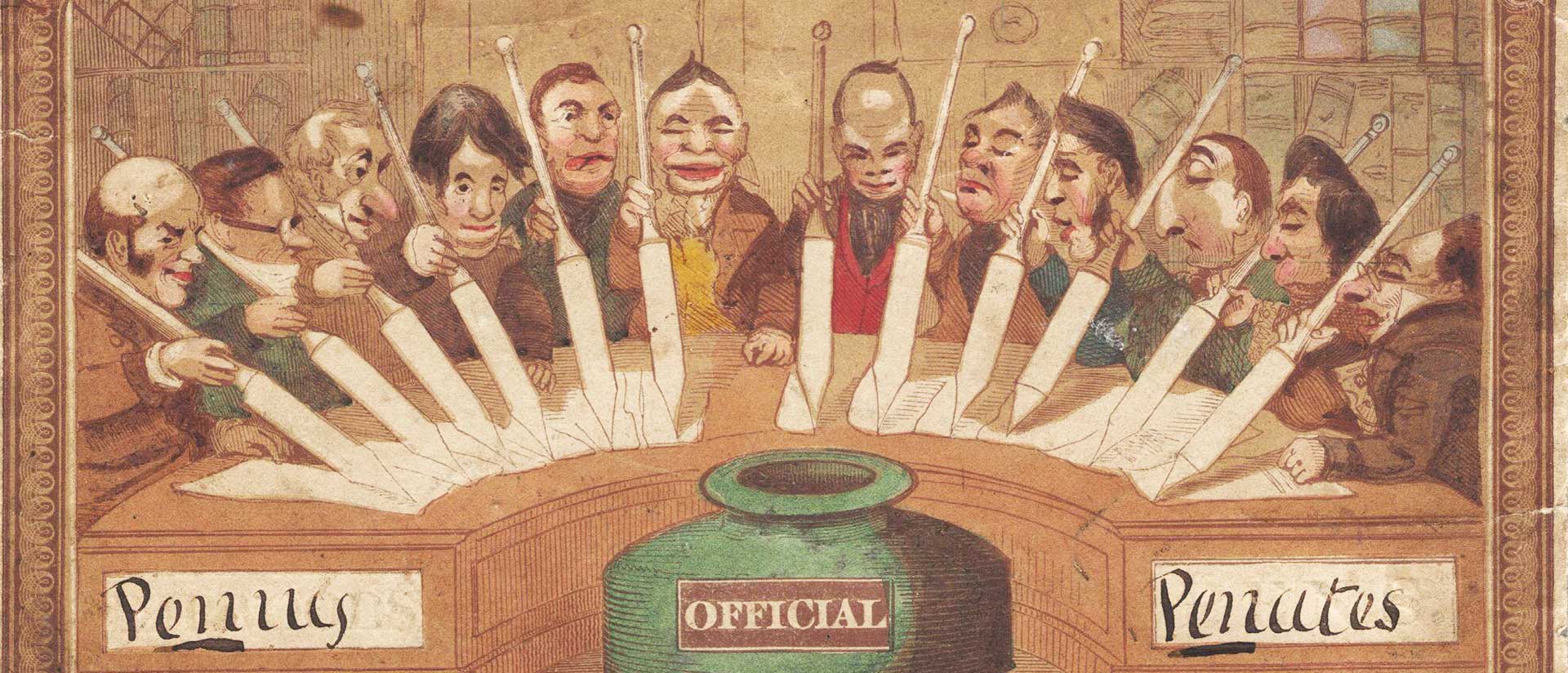

Even as these points were being negotiated, Nuremberg printers produced an unprecedented number of woodcuts and pamphlets about the siege, creating the first large-scale print-era propaganda campaign to rely on the Turkish threat. Through words and images, the prints emphasized the frighteningly swift advance of the Ottoman forces and portrayed scenes of violence and cruelty against civilians. Alongside litanies of suffering and lurid details of captivity, the presses also exhaustively discussed the terrifying discipline and fighting prowess of the Turkish troops, which made them undefeatable. An important attribute of these troops’ success was, according to the pamphleteers, the Christian origin of the janissaries. Well over a hundred pamphlets and woodcuts were produced between 1529-1530. That they were made by new-technology entrepreneurs without any known state support suggests their popularity and profitability. Among the results of this media blitz about Christian suffering at the hands of the Ottomans was the 1532 Peace of Nuremberg. With this agreement in place, many imperial cities mustered their citizens to serve alongside princely troops for the 1532 and subsequent campaigns.

Through words and images, the prints emphasized the frighteningly swift advance of the Ottoman forces and portrayed scenes of violence and cruelty against civilians. Alongside litanies of suffering and lurid details of captivity, the presses also exhaustively discussed the terrifying discipline and fighting prowess of the Turkish troops, which made them undefeatable.

Through this second mobilization of fear in commercially popular print and an array of imperial efforts, inflammatory rhetoric against the Turks proliferated. Along with speeches delivered at the imperial diets and recess promulgations, the imperial state also mandated prayers and processions seeking divine intervention and mercy for the German targets of the Ottoman threat. Over time, the state mandated church alms boxes for soldiers and civilians who had borne the brunt of Turkish military violence. The heightened antipathy toward the Ottomans made it possible for Habsburg rulers to gain broad public support for their Turkish policies during the subsequent decades.

The Habsburg court sponsored skilled personnel to produce and disseminate knowledge about the Ottoman military host and Ottoman society more broadly. The tradition of gathering information from those with first hand experience of Turkish domination, in particular through captivity, dated back to the second half of the fifteenth century. Ferdinand’s chief Turkish translator for over thirty years was a former captive. Urban Sagstetter, orphaned during the first Siege of Vienna, became court preacher and eventually Bishop of Gurk. Hugo Blotius’s first inventory of the Austrian National Library in the 1570s identified all the volumes on the Ottoman Empire so that military planners could access knowledge about their enemy systematically.

Important historical studies by Winfried Schulze, Reich und Türkengefahr im späten 16. Jahrhundert [Empire and the Turkish Threat in the late sixteenth century] (1978) and Karl Vocelka, Die Politische Propaganda Kaiser Rudolfs II [The Political Propaganda of Emperor Rudolf II] (1981) reveal the close links between the imperial political agendas and anti-Turkish propaganda. The empire imposed a larger, more regularized Turkish tax across all of the Holy Roman Empire, in order to fund the construction of a fortress system running along the southeastern border between Habsburg and Ottoman territory. The accompanying rhetoric (over 400 works were produced during the reign of Emperor Rudolph II alone) served to inspire payment of the tax. It unified the Holy Roman Empire by allowing its subjects to transcend the divisive topic of religious reform within “the Christian republic” and focus on what was now known as the hereditary enemy (Erbfeind), the Turk. The tax would also fund troops and material during various short hot wars and the Long War from 1593 to 1606.

With the close of the Long War, the Habsburgs and Ottomans settled into cold-war hostilities, until conflict again flared into open warfare in the 1680s. The 1683 Siege of Vienna ended quite differently from that of 1529. In 1683, the Ottomans were not the terrifyingly undefeatable enemy. Instead, the Ottoman siege was broken, and the Austrian military began pressing eastward, in a slow but heartening series of victories across eastern Europe. In that climate, fear of the Turks could be set aside for moral explorations of Turkish difference.

Yet even as Turkish fear in the public sphere was promoted by printers looking for surefire bestsellers, and imperial authorities seeking material support for their antagonistic policies against the Ottomans, another strand of thought towards the Ottomans existed in works authored by humanists and religious reformers. Some notable figures, in fact, praised the empire’s religious tolerance and diversity. A powerful response to the 1453 fall of Constantinople, for example, was composed by no less than Nicholas of Cusa. A German-born humanist who spent the bulk of his career in Rome, he wrote On the Peace of Faith in 1454. It called for religious peace and the tolerance of diversity, grounded in the idea that the divine Creator had sent many different teachers to the peoples of the world before the birth of Christ, thereby producing the different religions of the world. This strand of religious relativism was shared by other humanists in the second half of the fifteenth century. In less rarefied circles, a 1456 Nuremberg carnival play written by Hans Rosenplüt also playfully presented the Ottoman Emperor’s wisdom and virtue in contrast to corrupt officials and authorities in the Holy Roman Empire. Desiderius Erasmus advocated for religious peace, publishing essays in 1515 and in 1530 that held up Turks as virtuous foils for the many Christians who failed to live up to their faith’s moral demands. In Martin Luther’s 1518 explication of his “Ninety-Five Theses,” he argued against papal calls for a Turkish crusade, as part of his attack on papal remittance of sins. With the Siege of Vienna, Luther shifted his position to advocate for resistance to the “Turk.” This exhortation to resistance was paired with another calling for resistance to the papacy: while Luther has been held up as a strong promoter of antipathy toward the Turks, he did so in the service of another aim, the reform of the Latin Christian church.

Popular anonymous pamphlets also praised the religious tolerance of the Ottoman empire, suggesting that it was possible to find greater religious freedom to practice true Christianity there. While these pamphlets are often dismissed as satirical, in the mid- sixteenth century, a community of anti-Trinitarians who had fled the Holy Roman Empire in search of religious toleration formed in the Ottoman capital.

The questions that history asks about German-Turkish interactions are, of course, shaped by the public debates and questions swirling around the historians as they conduct their research. Winfried Schulze, for example, undertook research for his foundational 1971-74 study just as guest-worker recruitment was ending, and the number of Turkish nationals choosing to remain in Germany began to visibly outstrip those of any other nationalities. More broadly, archives are catalogued according to the priorities of the time that they were organized; their categories reflect, with good reason, the institutions and structures that produced the records. Thus, there is often a section in archives on the state administration of the Turkish tax, a topic of great institutional interest to local authorities—who sought to account for their responsible payment of these financial obligations—and to imperial authorities, who sought to prevent tax evasion. There is no corresponding section for quotidian experiences of non-elites.

In 2018, there are more nontraditional resources available to scholars. Their research no longer needs to rest exclusively on official discourses of the past, whether speeches and promulgated recesses of the imperial diets, sermons and publications by clerics and other writers endorsed by the state, or the print and manuscript texts of the humanists and reformers who shaped so much of the print discourses. Archival researchers can now uncover non-official histories with increasing success by utilizing the techniques developed by social and cultural historians to study women and colonized people. These methods underscore the importance of archival preservation and access to historical records, so that historians can investigate questions that have become freshly relevant. The evidence is fragmentary: the alms for a returning captive German or a captive Turk, a paid laundry bill, a salary list, a court case, a baptismal entry, a margin note in a printed book, a memento of a journey tucked into a manuscript, an ink sketch, or an inventory of death goods. These, in the end, are the quotidian traces that allow historians to move beyond official production and uses of the Turkish threat to uncover other histories of German-Turkish engagements across the centuries.

Image: Niklas Stör (ca. 1529-30), from Max Geisberg, Der deutsche Einblatt-Holzschnitt in der ersten Hälfte des XVI. Jahrhunderts, vol. 33, Munich, 1923-24. Courtesy University of Heidelberg