Writing Generations

A conversation with Frido Mann

By Veronika Fuechtner

This August 2017 conversation with writer Frido Mann (b. 1940), a grandson of Thomas Mann, was part of the research for my book project “The Magician’s Mother: A Story of Coffee, Race and German Culture.” In this book, I trace the Brazilian background of Thomas and Heinrich Mann’s mother, Julia Mann, née da Silva Bruhns (1851-1923), who grew up on her father’s plantation, the Boa Vista estate, in the coastal town of Paraty, south of Rio de Janeiro. Her great-grandson Frido Mann is an accomplished musician, retired psychology professor, and the author of several works of fiction and nonfiction, the latter on topics ranging from quantum physics to religion to music. His writing has engaged his family’s Brazilian history, including in his novel Brasa (1999), his autobiography, Achterbahn (2008), and the scholarly volume Mutterland (2009). Mann’s latest book, Das weisse Haus des Exils (2018), offers a timely reminder of Thomas Mann’s anti-fascist activism during his exile in the United States. Frido Mann is currently an honorary fellow of the Thomas Mann House in Pacific Palisades, California—a house where he spent parts of his childhood with his grandparents.

Veronika Fuechtner (VF): Your novel Brasa was a roman à clef in many ways. Firstly, it deals with the Brazilian roots of your family; secondly, it’s a novel that engages with certain texts—for example, your great-grandmother Julia Mann’s memoirs, Aus Dodos Kindheit (1903/published 1958), and perhaps also with your grandfather’s novel Buddenbrooks (1901). Thirdly, your novel is also an introduction to the history and culture of Brazil; you even included a glossary. Finally, it’s also a roman à clef for your family history.

Frido Mann (FD): Yes, many relatives do make an appearance. They may be transposed to Switzerland, and the generations are at times switched, but they are recognizable.

VF: You wrote in Achterbahn that Thomas Mann was not represented in this book. But it seems to me that he is present in its style. Brasa also deals with his literary legacy.

FM: Not consciously, but it must have been that way. I would say that was unavoidable. It just happened that I wrote in this genre, in this style. The association with Buddenbrooks is so clear that Thomas Mann doesn’t even have to be mentioned. His brother, Heinrich, makes a direct appearance as a protagonist, but not Thomas.

VF: I also noticed that you like to question the authority of the narration. For example, you often write, “it seemed to be that way.” Or there are passages that open up other possibilities—it could have been that way, maybe it happened another way—and then the reader doesn’t really know what actually happened.

FM: Yes, that’s possible. And in that context it’s important that my style doesn’t only draw from the German side. At the time, I was also very strongly influenced by Latin American literature, not Brazilian, but rather Spanish-language Latin American writers. My absolute favorite was Isabel Allende, who also writes family histories. She has this style, sometimes a bit drastic, that she supposedly picked up from Gabriel García Márquez: I am sure she doesn’t like to hear that, but it’s true, isn’t it? That’s what I did, too, at least a little bit—I picked it up from her.

I wrote Brasa in 1994 after I had read her novel The House of Spirits and saw the movie. Serious filmmakers were upset about the film because it’s a Zutatenfilm: a film with one ingredient added after the other. Still, I thought it was incredibly fascinating. But the original history of Brasa really started with another film. In early 1993, I went to see a film in Münster called Urga, by the Russian director Nikita Mikhalkov. I was so impressed—several generations, different countries, one truck driver. Urga is a javelin. When someone wants to start a family, they throw the javelin, and where it lands, the family settles. That’s the story, and it went through several generations and encompassed several countries, China, Russia, Mongolia. I knew I had to do this. But how? And then it occurred to me: Why would I go to Mongolia? Why not write about my own roots? I didn’t know anything about Brazil at that time; I really had to start from zero. I always had heard from my grandfather—yes, yes, my mother, Brazil, the parrots, and this and that. But I didn’t know anything beyond that. Then I started my research, and exactly at that moment, my great-grandmother’s memoirs, Aus Dodos Kindheit, were translated into Portuguese. She had written the book in German and it was finally to be translated into her mother tongue. Just as I was about to investigate my family’s history, I got an invitation by the Goethe Institute to come to the book launch of the translation. At that event, I could already say that I had written the first few pages of a novel, which pays homage to these memoirs.

VF: So, it’s fair to say that Brasa is also a roman à clef in yet another way: a key to your own story of researching your family history. It’s a key to your own relationship to Brazil, a country that also has a certain claim to this family history. The Brazilian sociologist Vamireh Chacon, for example, has said that Thomas Mann is also “one of us,” a Brazilian in family and spirit.

FM: When I was in Brazil for the book launch, there was a huge article in the daily Journal do Brasil titled “A volta da senhora Mann” (the return of Mrs. Mann). It was indeed a return. And, of course, they’re very proud that a Brazilian produced two Weltsöhne—two sons of world literature.

VF: Let’s get back to your novel Brasa. I was fascinated by the fact that Afro-Brazilian history and culture is given much more space than indigenous culture, which is more documented in your family as an influence. There were very vivid and haunting descriptions, especially regarding slavery.

FM: Yes, that’s correct. I also invented a maternal line in the novel that connects to the Boers [that is, to South African history] and also to Salvador, the north of Brazil. There is always talk of the indigenous origins, but I believed from the beginning that in Brazil you never know what kind of mixture there is. I was always told that there might be African ancestors one didn’t know about. (…) And then I was also fascinated by the fact that my great-grandmother Julia was friends with the children of slaves on her family estate, and that she preferred slave food—cheap meat and the black beans—to the red beans of the master’s house. This made an impression upon me. This history thus plays a big role in the novel—because that is Brazil.

VF: The Afro-Brazilian martial art capoeira, which was practiced and disguised by slaves as a dance, also plays a large role in the novel, actually even structures it. The novel starts, for example, with a quote from a song about capoeira, “Berimbau,” by Vinicius de Moraes. It’s about the battle between masters and slaves but also about battles between lovers. There are many avenues through which capoeira is expressed.

FM: Already in 1994, when I was in Paraty for the first time, there was capoeira every Saturday evening. In front of the Igreja da Matriz, the church in the town center, there were many trees, and then there were always two or three people who danced capoeira all evening. I just had to watch it. It was so impressive. Before, I only knew it from books.

VF: Your book also navigates the tension between nature and nurture, between culture, socialization, and differing origins. You joked to me in an e-mail that making caipirinhas is in your genes—é génetico. So what are we? Products of our education or of our genes?

FM: This question still looms large for me long after having completed the trilogy of which Brasa was a part. Particularly the question of how intellectual and spiritual systems like religion are a part of us. A monk at the Europa-Monastery, in the Austrian Salzkammergut, once told me: “The conflicts between the religions don’t stem from the religions but from the cultures they are a part of.” Religions all want the same thing. But they dress it up in different ways. And that’s where the misunderstandings or exclusions come in. In Judaism, for example, you think of being Jewish as an origin, as a people. Religion is tied to genes and a place. This is us and this is them. But if you start thinking beyond this, it makes no sense. And that’s what intrigued me about Brazil, this miscegenação, the diversity, that everyone lives with one another, even with all the limitations Afro-Brazilians experience in Brazil. They are not persecuted, but they are discriminated against. In the end, they are not equal.

VF: It is negotiated in different ways. It depends on class.

FM: Exactly, but in Brazil I always saw children playing together, black, brown, red, green (laughs)—everyone played peacefully together. But when they grow up, everything becomes a bit more serious. It’s not that way in the US.

VF: Yes, it’s very divided.

FM: It’s also not like that in Spain or Argentina, but it’s fantastic how it just happens in Brazil. Still, I am aware that you can’t idealize it in the way Stefan Zweig did in Brazil: Land of the Future (1941). Yet this mixture is an opportunity; there are possibilities. Whether these will be realized is another question entirely. Brazil remains a young society.

VF: It’s eternally young (laughs). That’s maybe also a curse.

FM: In good and bad ways. At first, European visitors are fascinated by the positive, but when they stay longer and take a closer look—the promise doesn’t always hold up. A German friend who lives in Paraty told me from the outset: “Don’t believe that Brazilians are as easygoing as they first seem. They’re much more complicated than us.”

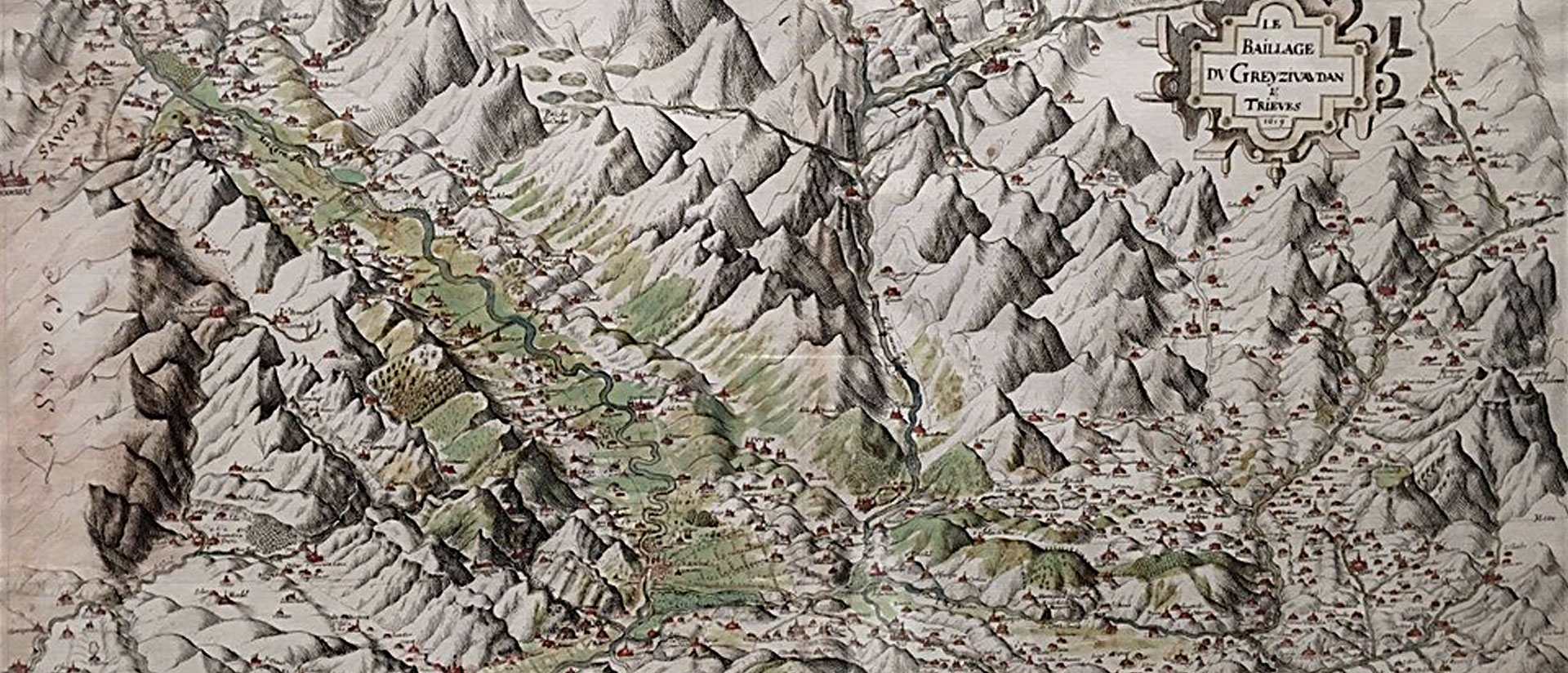

Image: Thomas Mann and Frido Mann, circa 1944, Los Angeles, California. Photo courtesy Frido Mann.