Deep Listening

Selling and defining the experience of “live” music

By Mark A. Pottinger

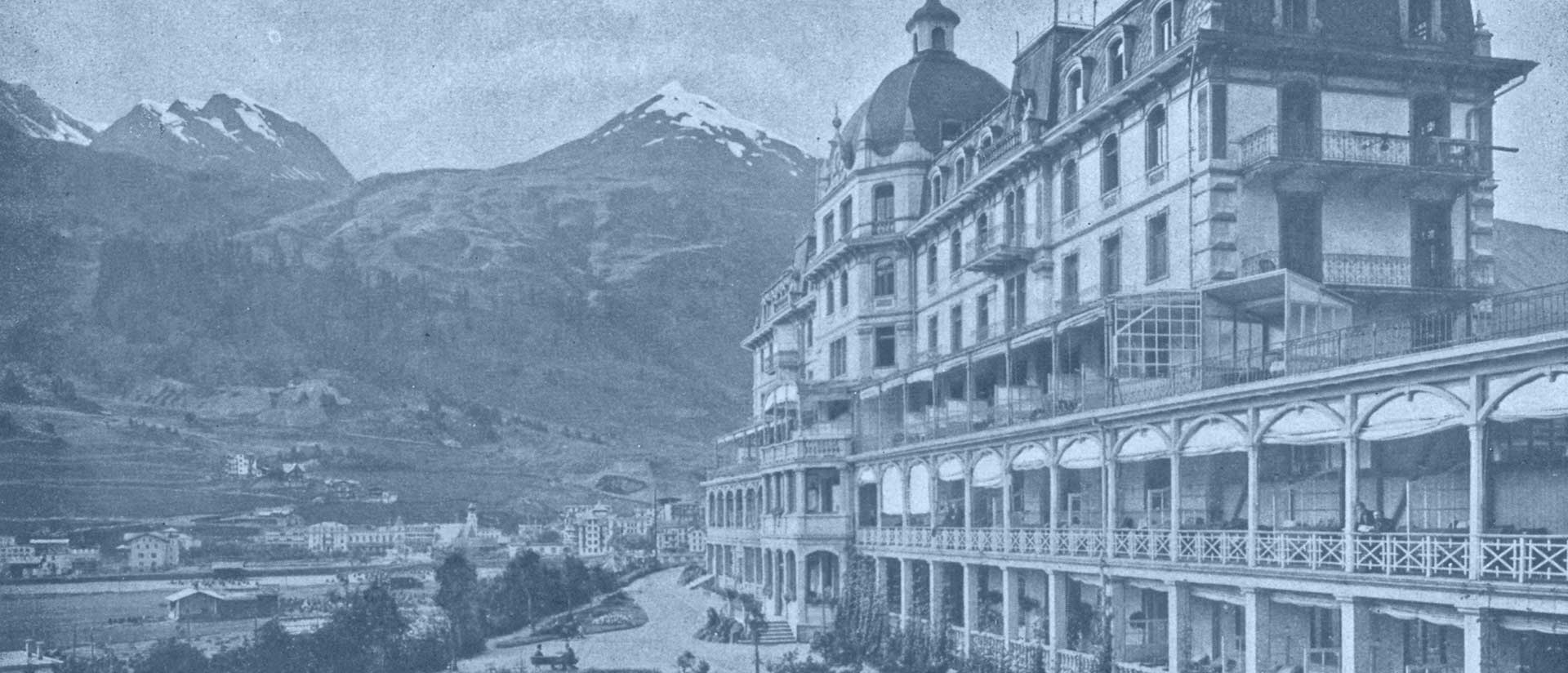

In February of this year, my wife and I visited the Elbphilharmonie, in Hamburg, where we were able to purchase two €2 tickets to visit only the grounds, gift shop, and surrounding plaza level of the hall. The €13 guided tour of the actual concert hall was sold out for months, as were all live music events. It is by far (then and now) one of the most difficult concert tickets to get in Hamburg, if not all of Germany.

Upon reflection, I was surprised to find such public interest not in what the hall is for or about, but in the hall itself—as if the very instrument to hear the music was the main thing on display. After speaking in late May with the artistic director, Christoph Lieben-Seutter, in a dialogue-lecture presentation at the US Consulate in Hamburg (arranged by the American Academy in Berlin), I left thrilled, but also unnerved by a disregard for the actual music he was presenting to audience members, some of who had never stepped into a classical music concert hall. Yet those same audience members, according to Lieben-Seutter, found themselves leaving after the first intermission because they had no interest in the actual music-making that was going on in the hall, where individuals of artistic worth and ability present the music of composers, some living, some dead.

The Elbphilharmonie has become a beacon of commerce and wonder, an amusement-park ride with little interest in the music or the people who make the music, only a rarified “experience” to highlight on social media and for individuals then to move on to the next big shiny thing. Even Lieben-Seutter conceded this fact, and estimated that, due to the overwhelming curiosity of the public, in three to four years, when interest has waned, he will then have to focus on concert programming more rigorously.

Hamburg, of course, is not alone. From Los Angeles to Paris to Shanghai, architecture and its patent-filled acoustics have come to define the live music experience of classical music in the modern concert hall. Starting with the work of Wallace Clement Sabine (1868-1919) in 1895, when the young Harvard-educated physicist examined the reverberation time and absorption material of a lecture hall on Harvard’s campus, the science of architectural acoustics was born.

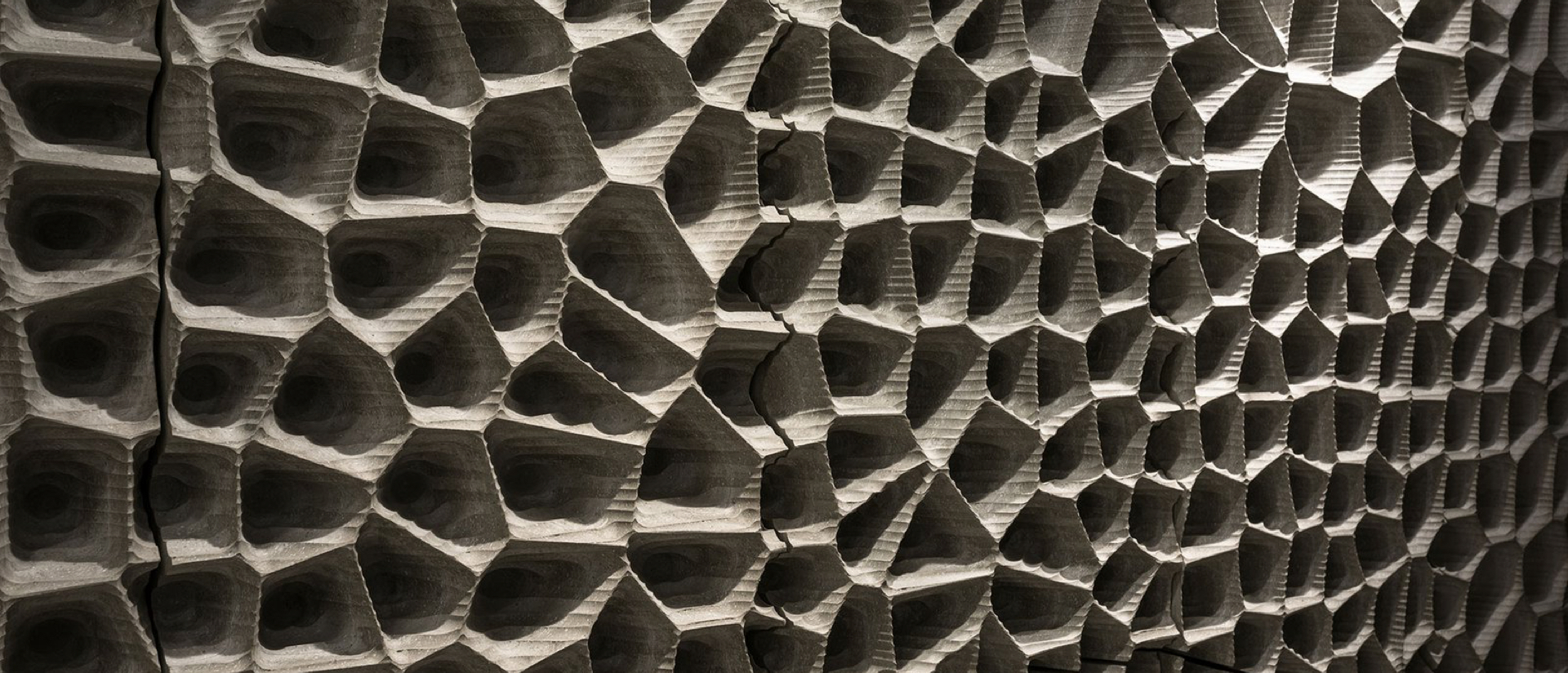

Today, concert hall acoustics are big business, so much so that Yasuhisa Toyota of Nagata Acoustics, the famed architectural acoustician of the new Elbphilharmonie in Hamburg, has patented a so-called “perfect acoustics,” which define a live music experience like no other. In such a space, one is able to get closer to the music than ever before, while at the same time eliminate spatial echoes, so-called “dead spots,” and noise-like resonances—in essence, the natural-occurring sounds that get in the way of the music. Of course, this is a reality one has with sound recordings today. The disembodied nature of sound recordings help to isolate the sound source from the sound signal to such a degree that we come to consume only the revered sound and not the actual person who produced it.

In such a space, one is able to get closer to the music than ever before, while at the same time eliminate spatial echoes, so-called “dead spots,” and noise-like resonances—in essence, the natural-occurring sounds that get in the way of the music.

The live music experience has, as such, become a reflection of digital music recordings with a preference for “smooth,” un-grainy resonances. The acoustically enhanced, technology-equipped concert hall of today is no longer a space for human-filled sounds (e.g., the breathing, the scratch of the fingers, the buzzing of the lips, the smack of the tongue, the slip of the feet—the actual sound of music making) but rather a temple dedicated to the fetishization of a “pure” un-human sound for the individualized consumer, who more often than not hears music as a self-directed activity and not as a shared communal experience. And yet, this focus on a particular pure sound of the music also reflects a corporatization of certain types of sound, a synergetic business practice of fixing the equalization (EQ) of the music, so that the public desires and pays for a pre-manufactured standard to the sound of the live music we come to hear in the concert hall, mirrored by the recording studio.

Along with the Elbphilarmonie in Hamburg, which opened with spectacular success in January 2017, Yasuhisa Toyota and his Nagata Acoustics Company have brought their brand of acoustical purity to several concert halls throughout the world, including numerous music venues throughout Asia, Europe, and the United States: the Philharmonie de Paris, Mariinsky Theater in St. Petersburg, and

Disney Hall in Los Angeles, to name a few. When expanded to drama stages, movie theaters, lecture halls, churches, exhibition spaces, and sports arenas, one begins to see the large reach and influence Nagata Acoustics has in the business of architectural acoustics, feeding the desires of the public and architects alike to create an enhanced sound experience within an enclosed space. One can only imagine that once Toyota enters the headphone or speaker industry, there will be a “sameness” to our listening experience of music that will break down one’s understanding of what is natural and what is not, leaving the consumer confused on what is fake and what is real.

It can be argued then that the materialization of sound through digital devices and enhanced architectural acoustics has stripped music of its unique communal universality (its “aura,” in the words of Walter Benjamin) and turned it into a trademarked-stamped product of individual consumption. This, of course, is highlighted in the economics of the concert hall today, as theater directors work to sell-out the hall and make it profitable through business practices like “demand-based pricing” and the “scaling of the house.” Demand-base pricing, a common business practice of the airline industry, raises the base cost of a seat owing to the high demand during the holidays or a popular day or time of the week. This is separate from the idea of “scaling the house,” which is setting seat prices by examining the sightlines to the stage from various locations in the hall and the overall distance of each seat from the stage. Such practices, albeit ubiquitous in theatrical management ever since the rise of the middle class and their ability to purchase seats outside of royal privilege, limit what one hears and sees, making music once again less about a shared content or message and more about one’s economic ability to consume privately and make it their own.

It can be argued then that the materialization of sound through digital devices and enhanced architectural acoustics has stripped music of its unique communal universality (its “aura,” in the words of Walter Benjamin) and turned it into a trademarked-stamped product of individual consumption.

In order to maintain such selectivity and a claim of “you get what you pay for,” the individual in the modern concert hall is tightly controlled, so that one cannot speak, must silence all electronic devices, does not clap in between movements, does not cough or move when the music begins, and must, in essence, mute all aspects of oneself in order to hear the music. In spite of the complete corporeal control, however, it can be argued that the concert hall remains a space for the individual to practice the communal definition of self, allowing one to acknowledge that culture is a shared activity and its ability to resound depends on our individual respect for one another’s right to listen “separate but equal.”

And yet, paradoxically, the concert hall is a place that is removed from everyday society. From its earliest origins in Ancient Greece, such as the theater at Delphi, the hall was seen as a space where the oracle or priestess, the human messenger of the gods, became not a reflection of herself but of the very cryptic and bizarre message she presented. She was oracle incarnate, message not messenger, music not musician. It is no surprise then that this original analog to the live music experience, the theater at Delphi, which is further reflected in the disembodied nature of the sound recording today, was used as a source for the Elbphilharmonie as dictated by its creators, architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron. Similar to the unworldly reality of the theater at Delphi, a space to hear the voice of Apollo, the enhanced acoustics of the modern concert hall provide a listening experience that goes beyond the everyday, making it a heightened reality, a magical space for new sound wonders to occur. The transformation from naturally occurring sounds to enhanced acoustic reality thus becomes reflective of society’s desire to go beyond the self and to engage in something larger that binds us all together.

The transformation from naturally occurring sounds to enhanced acoustic reality thus becomes reflective of society’s desire to go beyond the self and to engage in something larger that binds us all together.

The music we now hear in a more acoustically heightened and pre-manufactured sound space remains the legacy of society wanting to go beyond the everyday in order to embrace the simulated, the virtual, the non-real, the “authentic fake” (to use Umberto Eco’s words). What does it mean that music is not reflective of an actual sound source but a filtered reality that convinces us to give up on our natural ability to see and hear the truth around us? What is the “live-ness” then of a performance? What is truth in hearing? I would argue that the modern concert hall, in this consideration—a space separate from the everyday experience of naturally occurring sounds with its sound reflectors, absorbers, and resonators—is a mirror of contemporary politics and the search for accuracy and truth in the message.

The title of this essay is “Deep listening,” which is a subtle conceit for individuals to go beyond the surface, the immediate surface that tends toward passivity and leaves one content to hear and see what is already familiar. The phrase comes from the work of Pauline Oliveros (1932-2016), the American experimental and electronic art music composer, who performed and recorded in unconventional spaces, some deep in the Earth, in order to get “trained and untrained performers to practice the art of listening and responding to environmental conditions in solo and ensemble conditions.” Her critical writings and compositions asked the listener and performer for an increased “sonic awareness” of the sounds and sound producers of the listening environment. To listen “deeply” in this regard is to ask the individual for a more critical, deeper form of engagement with the world out there. In this way, one then starts to become aware of the content of what one hears and sees, lending towards freedom of self and agency to counter the institutions or people who seek to take it away.

The condensed frequencies of an mp3 recording and the “microphoning” of enhanced 3D-stereophonic sound reproduction through acoustic sound-reflectors and absorbers both represent a step either to limit or to augment, respectively, the human sound experience. “Deep Listening” is what is required for the listener to go beyond the passivity of pre-manufactured sounds and the trusting of institutions to frame our musical truth. One must return to the sound source, the very individuals who wrote the composition, in order to remind us that the power of music does not rely upon the filtered or amplified message alone but the individual who gave birth to it. If such an understanding is not heeded, then we become a society lacking self-reflection and the clarity to know what is real and what is an “alternative fact.”

Photo: Johannes Arlt. Courtesy Elbphilharmonie Hamburg.

Mark A. Pottinger is an associate professor of Music and interim department chair in the Visual & Performing Arts Department at Manhattan College. During the spring 2017 semester, he was a Nina Maria Gorrissen Fellow at the American Academy in Berlin. He is currently working on a book called Science and the Romantic Vision in Early Nineteenth-Century Opera, to be published in 2018.