Museums, Architecture, and Social Engagement

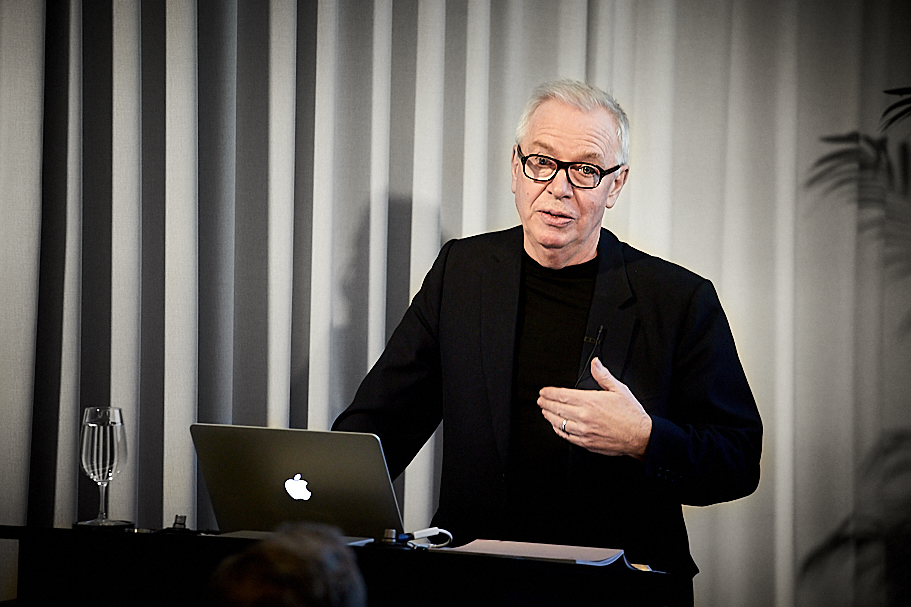

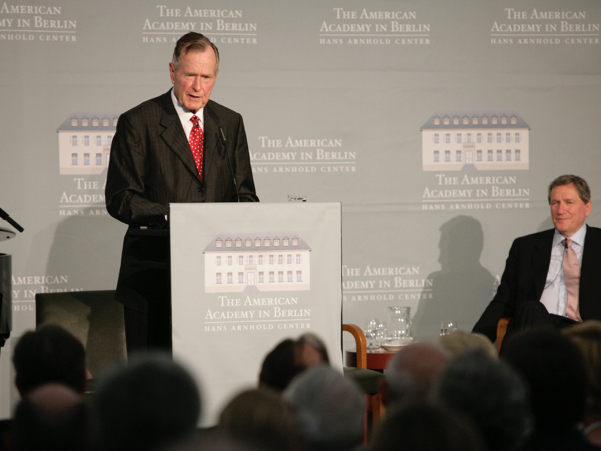

Two speakers at the American Academy during the week of March 18 took up a perennial topic: the role and responsibility of art and culture in society. Daniel Weiss, the president and CEO of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, spoke about the social responsibility of museums, and Sir David Chipperfield gave a talk about the social responsibility of architects. Both speakers—whose topics ironically had not been coordinated in advance—were here as Marina Kellen French Distinguished Visitors.

Museums have a dual role, Weiss said: to educate and entertain. That can sometimes mean dealing with topics that are shocking or controversial. Still, “too often we see in the museum world a fear of engagement with fundamental issues in society,” Weiss said. The key is to provoke debate, and if that means some people want to protest certain works of art, that’s fine, he said, as long as it doesn’t interfere with other attendees’ experience of the museum. Though some visitors are looking for a place to debate social issues—and as a curator Weiss acknowledges he is “comfortable making people uncomfortable”—many of The Met’s visitors are seeking something quite different altogether: a place of stability and beauty. This is the dual role, “but it is not a contradiction to have beauty and to provoke.”

For his part, Sir David Chipperfield said that his 11-year project to restore the Neues Museum, which reopened in 2009, “was an extreme example of the relation between architecture and society.” Today, he thinks that relationship is struggling. “It stresses me that architects have become detached from planning, and that planning has become a reactive rather than a proactive process.” This is important, Chipperfield says, since urban planning is particularly necessary now. When people talk about “a housing crisis,” for example, they should also look at this as a “housing opportunity” for planners to make cities more livable.

The Met has come a long way from its early days, when it was first opened in a small rented building on Fifth Avenue, in 1872. It has since expanded to a complex of halls with more than two million square feet of gallery space and two million works of art and an annual budget of over $300 million. “In many ways, the Met is one of the most interesting and successful social experiments in American history,” Weiss said. “The Met looks and feels to me more like a university than an art museum,” he noted. “All of the art, from 5,000 years, is in one building.”

Weiss said that the biggest single draw to the museum was the Costume Institute, with 33,000 items of clothing that stretch back to the fifteenth century. Beyond New Yorkers’ particular fascination with fashion, however, there are some complex issues that increasingly face museums, Weiss said, starting with: “How do we engage with art from other cultures?” Despite its aim to cover 5,000 years of art history, “there are many cultures for which we have no representation.” Weiss points out that out of The Met’s 16 curatorial departments, just two represent 90 percent of the planet: the Department of Ancient Americas, Africa, and Oceania, and the Department of Asian art. “The world is shifting. […] Our organization needs to evolve with those shifting perspectives, and we need to do justice to our increasingly sophisticated view of what our global constituencies do.”

Provenance research—and sometimes the restitution of artefacts to their place of origin—has also grown in museological importance. “We are an actively collecting institution,” said Weiss, “and that is a perilous thing to do.” He cited the example of the golden Coffin of Nedjemankh, an Egyptian coffin that The Met had bought in 2017 but whose provenance documents were later shown to have been forged. The Met returned the coffin to Egypt earlier this year. “The world of ancient acquisitions is fraught with peril.”

On the question of funding, Weiss said that “over time, all nonprofit institutions will see their costs rise in excess of revenues.” The Met receives just nine percent of its funding from government coffers, and Weiss said it is important for all institutions to look at co-investment and diversifying their donors in order to remain economically sustainable. “You should avoid becoming dependent on the government or one big donor.”

As to whether the museum should refuse money from controversial donors, Weiss brought up the sponsorship of a Met gallery by the Sackler family, who founded the company that makes OxyContin, an opioid linked to heavy addiction and overdoses. Weiss said that the museum engaged the controversy head on and has initiated an ongoing, expanded debate on the issue. “The museum has not ‘not’ commented.”

Discussing architects’ need to take on greater social responsibility, David Chipperfield talked about his Fundación RIA, a nonprofit foundation he set up in 2017, in Galicia, in northwestern Spain. The foundation’s aim is to revive the economically struggling region by helping the development of industry, urban regeneration, and preservation of the natural environment along the beautiful coastline. “You can’t protect the environment if you just talk about protecting nature,” Chipperfield said. “You need to take into account the future of peoples’ lives.”

The Ría de Arousa coastal region where Chipperfield focuses his efforts has seen a persistent loss of young people to the richer parts of Spain. “If you want young people to live in a place, you need a strong identity of place.” This means making their towns more pleasant places to live. Chipperfield cited the grim urban conditions of many towns in northern England, where people voted heavily to leave the EU in the 2016 referendum. “Brexit is very much fueled by people who are unhappy—it is partly economic, but partly about their living space.”

Chipperfield described how his team of architects has tried to engage the local community to find ways to develop economically while not damaging their natural resources, notably the marine environment. “It is not viable to see architecture and planning separately from economic conditions,” he said. The ability to link things together is critical to the ability to plan. “As architects we are trained to link things together. This is our talent.” (For more on this subject, listen to the Academy’s podcast with David Chipperfield.)

Museums can have beautiful artefacts; architects can design beautiful buildings, but if they do not serve some greater social good, Weiss and Chipperfield suggested—then both are missing their mark.

I would be delighted to hear your comments about this or any other program at the American Academy in Berlin. Please feel free to email me at terry.mccarthy@americanacademy.de.

Terry McCarthy

President