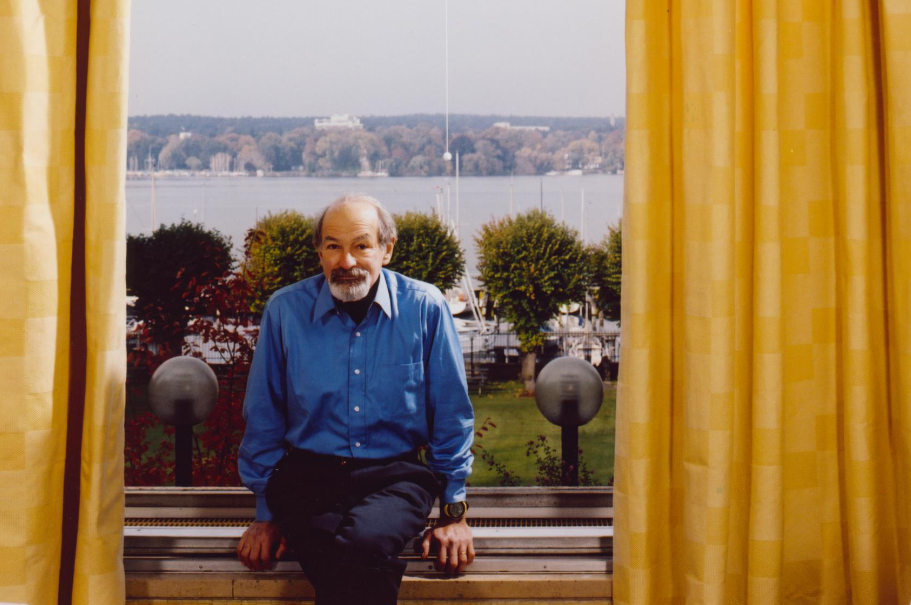

Timothy Snyder on Language and “Not-Even Fascism”

How did we enter the contemporary world of polarizing politics and encroaching authoritarianism? All seemed fine after the Wall fell and communism disintegrated—until it was fine no longer. Yale historian Timothy Snyder thinks we in the West became unreflective, and lazy in our use of language. Speaking at the American Academy in Berlin on January 14, at an event co-hosted with Intelligence Squared Germany, Snyder said that authoritarian ways of thinking have actually been enabled by liberal ways of thinking that discredited commonsensical truth, diminished the significance of the state, and refused to admit alternatives to the liberal way of seeing the world.

The idea of the “end of history,” bandied about thirty years ago, is particularly aggravating to Snyder. He says it blinded us to the vagaries and complex changes of the past, and “without history, we also lose responsibility for shaping the future. […] We no longer see that because all things were possible that all things are still possible.” That leads to what he calls a “politics of inevitability,” which blithely assumed that things would keep progressing the way they were, and that the future would be better than the past.

As a historian, Snyder knows that time moves calmly into the future for a while, but then it breaks—as in the financial collapse in Russia in 1998, the attacks of 9/11 in the US, or the burst of the housing bubble in 2008. At this point, the “politics of inevitability” turns into the “politics of eternity,” when people get the idea that the state cannot do anything, responsibility disappears, and “the ‘innocent people of the nation’ are under assault from outside.” This brings us, says Snyder, to a politics heading towards fascism.

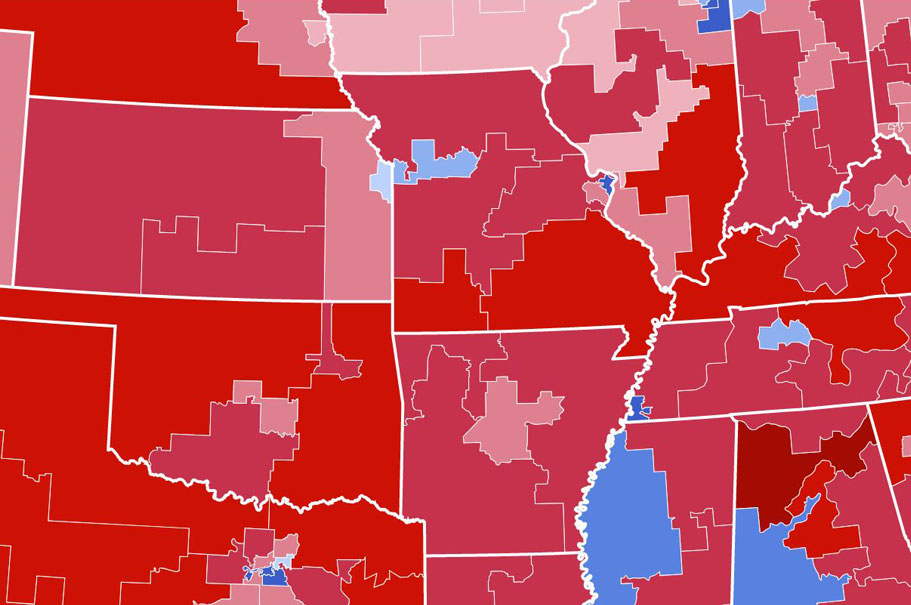

The wall the current US administration is proposing to build along the US-Mexico border is, according to Snyder, “a great example of fascist politics.” His last two books—The Road to Unfreedom and Tyranny—sounded warning signals about the threats to Western democracy from the rise of authoritarianism around the world. The slogan “Build that wall,” Snyder says, “is a tribal scream: we need a barrier between us and them.” But where did the slogan come from? It was chosen by algorithms, he notes, “tested by Cambridge Analytica on millions of Americans.” But two years later, there is still no wall. “And there will never be a wall. The phrase alone is the thing-in-itself.” In this way, “build that wall” is connected to a state of exception, or a state of emergency, serving a political purpose.

Snyder’s antennae for the creeping influence of undemocratic thinking and deceptive language are acute, but his use of the term “fascism” did not go unchallenged at this Academy talk. Some audience members claimed that this blanket use of the term undermined its historical significance, particularly in Germany. But, Snyder argued, “fascism exists, and it existed in history, and we need to keep returning to the history of fascism because it allows us to see things in our present world that we might not otherwise see.”

To be clear, Snyder is not arguing that the fascism of Hitler is recreating itself today; he terms current extremist politics “not-even fascism.” The Nazis wanted people out in the streets demonstrating; the not-even fascists want people to say at home in front of screens, on the couch, alienated. And while Hitler tried to create a new empire in Eastern Europe and Western Russia, the ”not even fascists” want to go back to the nation-state—while at the same time maintaining a link to other authoritarian leaders, most notably Vladimir Putin.

Asked about Russia, Snyder said that in some ways they are smarter than we are: “If the Cold War were about intelligence, we would have lost,” he says. The Russians couldn’t keep up with US economic production, which lost them the Cold War, but now that Moscow is again taking on the US, its intelligence operations are helped enormously by the massive scale and free availability of social media. “The price of a tire on an F-35 (fighter plane),” Synder noted, “is the same amount as the entire Russian cyberwarfare budget.”

In certain key indicators, Russia has already surpassed the West, Snyder said: the offshoring of wealth, inequality of incomes, and time spent in front of screens. Few in Russia believe in the rule of law or in the truth, he suggested, and unlike in the days of the USSR, Russia today has no vision to offer. They just want to discredit the West and its systems.

To prevail in the battle of values, Snyder says we have to be careful how we use language, but we must also address the dearth of local news, the rise of inequality of wealth, and the assaults on digital privacy. Most of all, we have to fight for democracy, because “if democracy is receding, that means democracy is receding in each one of us. […] We need to catch ourselves, observe what is going on.”

This is why Snyder is so insistent on including the theme of fascism. “The history of fascism shows there were many people who were not literally fascists but who were drawn along by a chant or some words.” By studying the history of fascism—which, Snyder said “is not an on/off switch; it started before 1933 and continued after 1945”—we can diagnose the weaknesses of democracy, and “think into the future.”

I would be delighted to hear your comments about this or any other program at the American Academy in Berlin. Please feel free to email me at terry.mccarthy@americanacademy.de

Terry McCarthy

President