Ben Rhodes on the Two American Stories

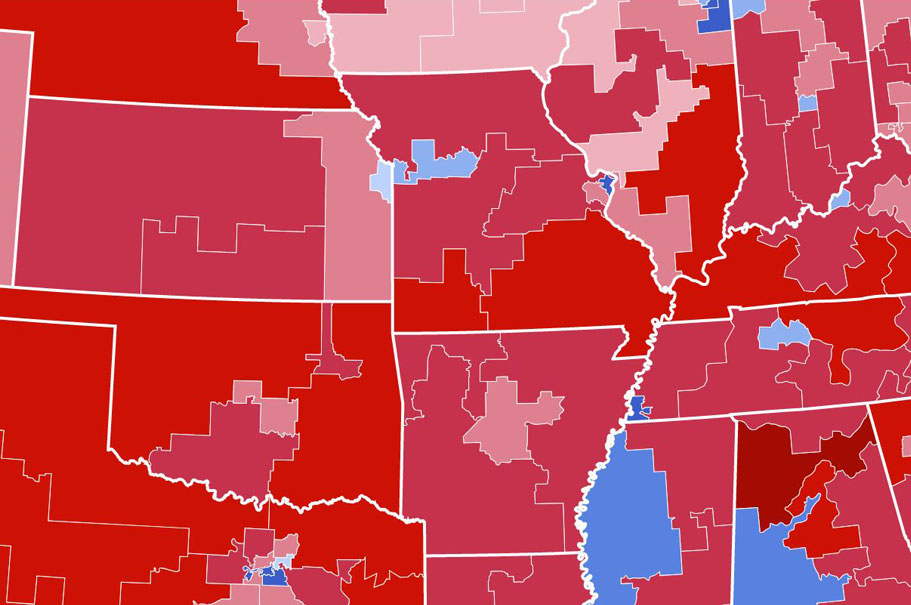

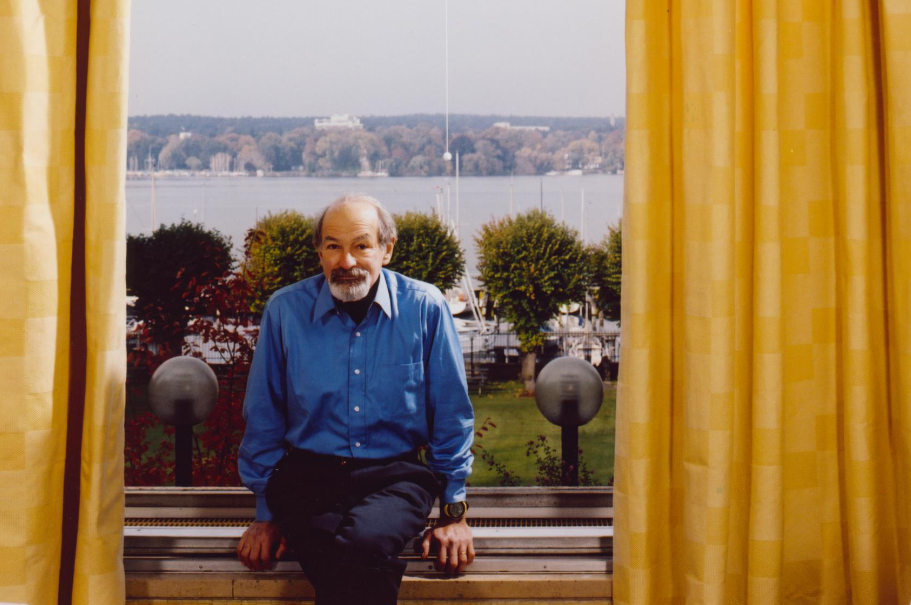

The United States has always had “two different parts” to its story, said Ben Rhodes, former deputy national security advisor and speechwriter for President Obama. Case in point: the presidencies of Barack Obama and Donald Trump. Rhodes listed some of the key foreign-policy achievements of the Obama White House: the Iran nuclear deal, the opening to Cuba, the Paris Climate Change Accord. “Obviously we have a very different president now.” But although Trump is dismantling those agreements, Rhodes said he is not dismayed. “America has always been a place of contradictions,” he said, pointing out the Declaration of Independence was written while part of the US population was still enslaved. In fact, he said he appreciated how Trump’s election rattled liberals out of their apparent tacit belief that there was “an inevitability to the world’s heading towards inclusion and diversity.”

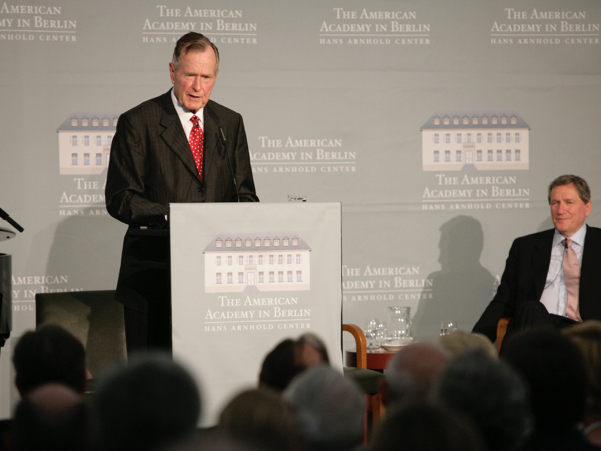

Speaking at the American Academy in Berlin on February 14—and again the next morning at an American Academy breakfast discussion at Café Einstein Unter den Linden—Rhodes said that American institutions—particularly the judiciary and the media—had shown resiliency in the face of assaults from the Trump White House. The exception was the Republican Party in Congress, which Rhodes said had decayed so much that it first allowed someone like Trump to be elected. Since the election, it has made little effort to say the Congress should be independent of the president.

Rhodes pointed out that Obama’s presidency was bookended by trips to Berlin: the July 2008 speech, during the campaign, and the final visit to Chancellor Merkel, in November 2016, after Trump had been elected. Merkel was the foreign leader who Obama most admired, said Rhodes. She was mostly cautious in making policy, but “when there was a necessity to defend Europe as an idea, she was a bold politician.” Rhodes also cautioned against the transatlanticism fatigue some observers are expressing. “In a world in which there are more centers of power, it’s more important that Europe and the US work together.”

The most controversial foreign-policy issue during the Obama presidency was the decision not to bomb Syria after President Assad’s use of chemical weapons in 2013. Initially, Rhodes had been pushing for the US to intervene in Syria, but when Obama decided against a missile strike in August 2013, Rhodes said he ultimately came to see it Obama’s way—“I had to confront the limits of what America could achieve.” And a single missile strike would achieve little, Rhodes said. “If you are intellectually honest about it, we would have had to have kept bombing and ultimately to have removed Assad.” But the US public did not want Americans fighting in another Middle Eastern war. Rhodes was—and clearly still is—uncomfortable with the affair. “I was spokesperson for Syria, and I took a lot of heat for it.”

The overarching criticism of Obama was that he was weak in foreign policy, and spent too much time apologizing for US mistakes in the past. Rhodes said Obama was simply trying to learn from mistakes made. “It is very rare for an American president to acknowledge limits, but it is important, because if you don’t, that is how you get into Vietnam or Iraq.” Which led to the much-pilloried Obama maxim: “Don’t do stupid stuff.”

One issue Rhodes said was vastly underreported was the amount of racial animus directed at Obama throughout his presidency. Obama avoided confronting the issue head-on to avoid being classified as “an angry black man,” and was aware he couldn’t heal America’s racial tensions in eight years. “But he knew that black children would see themselves differently after he had been in office—and white kids might see black kids differently.” Rhodes pointed admiringly to the racial diversity of the new members of Congress in 2018 and the candidates for the presidency in 2020. “They look like a 2008 Obama rally. …They are “Obama’s legacy.”

Since Obama left office, Russia’s interference in the 2016 Presidential election campaign has also taken on enormous importance, with claims that members of Trump’s campaign team were somehow involved, and charges that Obama’s administration did not do enough to expose it. Rhodes said that although the White House knew the Russians were hacking Democratic campaign emails in the summer of 2016, it was treated as a cyber-attack, and they did not realize how disinformation was subsequently being spread via social media. Obama was concerned that if he came out and accused the Russians of spreading disinformation, he would have been seen as being partisan. An attempt to get a bipartisan statement condemning Russian interference was blocked by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, said Rhodes. “We played it by the book, which is why we were behind the curve.”

It wasn’t until after the elections that the extent of the Russian involvement became clearer. A Trump transition team member said to Rhodes, “I think it is odd that Michael Flynn is meeting with the Russian ambassador before he is meeting with you.” This led, on both sides (Obama and Trump teams) to “a kind of freak out” when they realized the extent to which the Trump team had been in touch with Russians.

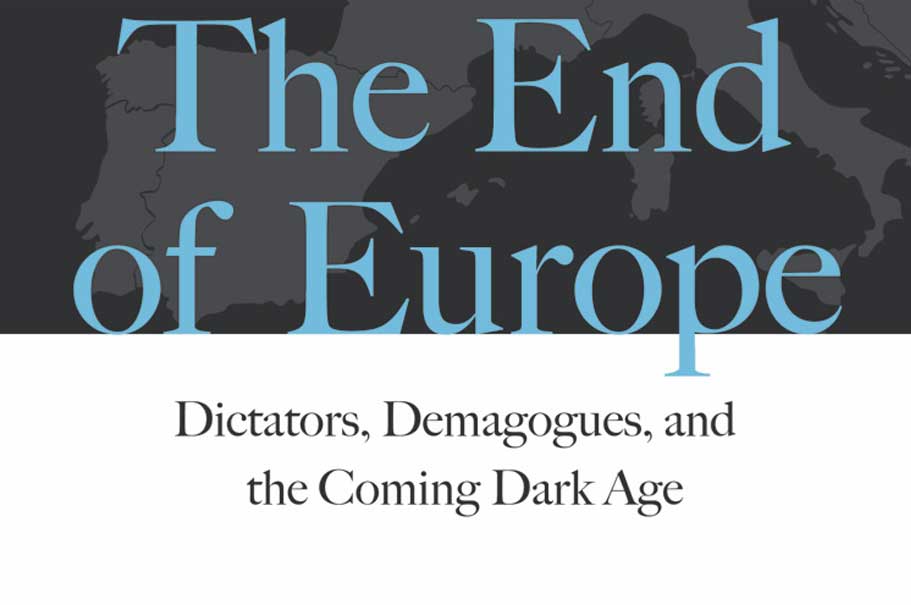

Rhodes began his book, The World as It Is, with the question “What if we were wrong?” The twin phenomena of Brexit and Trump’s election seemed to contradict the basic tenets of the world as Obama envisioned it, which left Rhodes cold: “This brand of politics and the populists only ends in one place—there will be a war—we need citizens to fight back to preserve their values.”

But he said he was optimistic that the US would bounce back, adding that Germany’s role in helping to “reintroduce the US to the world after this era” will be key. “There is more need for the transatlantic relationship now than there has been since the height of the Cold War.”

Rhodes ended with an impassioned plea for ordinary Americans to get involved in politics again. “They [populists] need people to be cynical and give up; that’s the only way they win.” He said he believed that America would be galvanized into action. “I could be wrong, but if I am wrong I have bigger problems than the fact of being wrong.”

I would be happy to hear from you at terry.mccarthy@americanacademy.de if you have any comments about this program or other ideas about the American Academy in Berlin to discuss.

Terry McCarthy

President