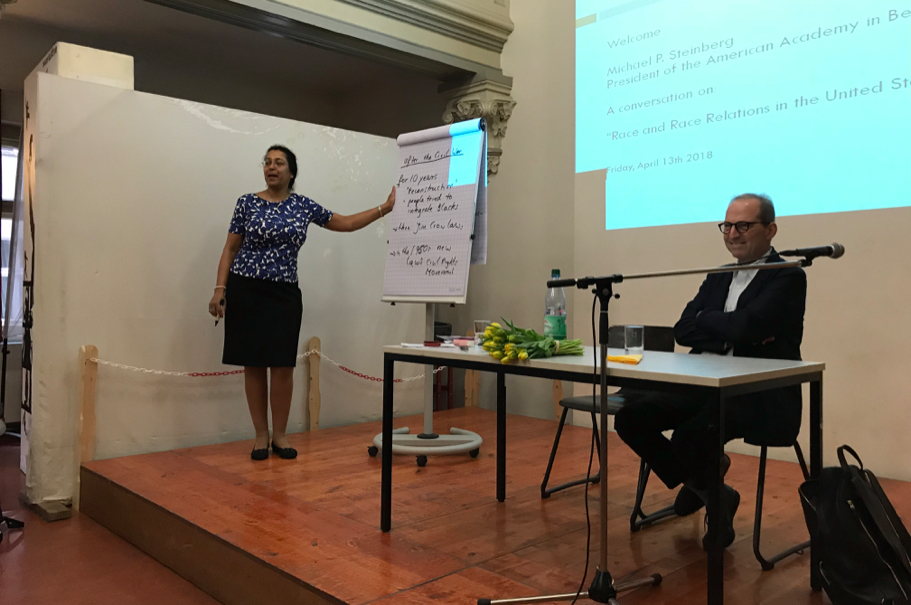

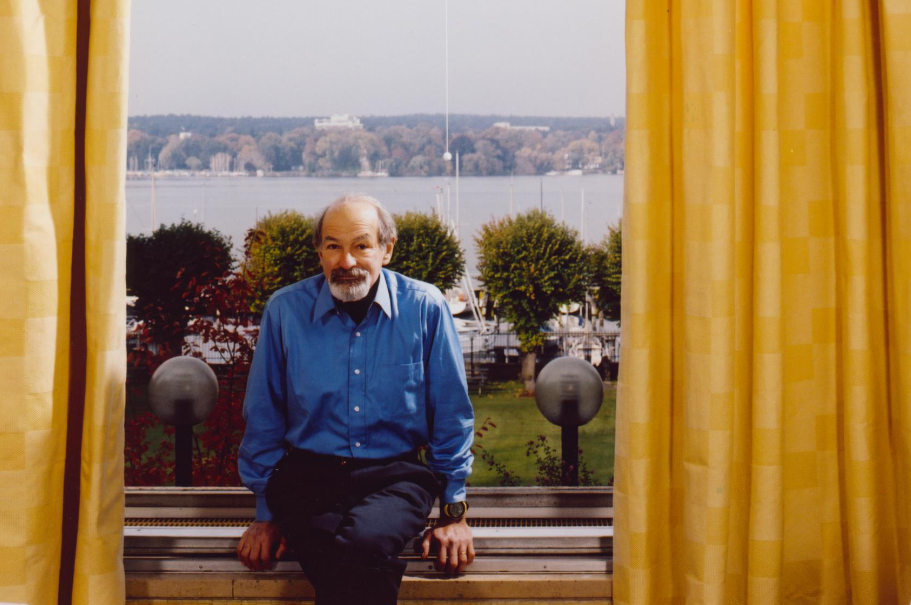

William Drozdiak on Emmanuel Macron and the Future of Europe

President Emmanuel Macron of France believes Europe has reached “a huge moment” in its history, where the peaceful democratic consensus that has reigned since World War II is under threat by extreme nationalists. He is also disappointed about the lack of support from other European leaders in countering this threat, according to William Drozdiak. Addressing a breakfast meeting at Café Einstein Unter den Linden on November 13, Drozdiak, a former president of the American Council on Germany, said that Macron is particularly upset that Chancellor Angela Merkel has not kept what he sees to be her end of the bargain: he would reform the French economy on the understanding she would help him with Europe-wide financial reforms.

“Macron has a close personal relationship with Merkel,” said Drozdiak, now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a consultant with McClarty Associates. “The optics of the Merkel-Macron relationship are touching, as seen this past weekend at the Armistice ceremony.” But the policy differences over Europe are glaring, according to Drozdiak, who has interviewed Macron at length three times this year in preparation for a book. “Macron is frustrated with her timidity in moving forward on reforms such as banking integration.” Macron is trying to make the case to Merkel that it is in Germany’s interest to bolster reforms, most immediately to find ways to spread the risk of financial chaos should Italy have trouble in servicing its enormous debt loads. Drozdiak said that Merkel is wary, even as Macron tells her that in her final time as Chancellor now is the time to embrace reform. “This is the moment Germany should be stepping up. The best future for Germany involves a strong Europe.”

But despite Merkel’s efforts in the past to solve Europe’s financial problems, Drozdiak said that she is not instinctively attuned to Europe. “She grew up in the East, so she is not emotionally invested in the EU in the way that, say, Kohl or Mitterand was.”

Italy, too, is an ongoing source of concern, said Drozdiak. Its current populist government reflects frustration and anger among a people whose economic growth has been stunted. The Italian economy is smaller now than it was in 2000, and in the south, 50-60% of young people have no jobs. Macron has a similar problem with high youth-unemployment in France, and knows this could destroy Europe “if young people are tempted by the extremes.”

Macron sees Europe’s future taking one of two starkly different paths, according to Drozdiak. “Macron says the old division of politics into Right and Left no longer applies. Now it is openness versus nationalism—and nationalism means war.” Macron believes the best way to halt extremism is to integrate the EU more closely, but over and again he is told by other leaders around the EU that “this is not the time for more Europe.” Macron is particularly anxious about next May’s European elections, where he fears extremists could make huge gains. Is he pushing too hard? “Yes, he is young and impatient, but he sees the dangers.” In his interviews with Drozdiak, Macron has said he does not want to be “one of the sleepwalkers” as Europe marches into the abyss.

As for the US, Macron is dealing with Trump on his own in Europe because Merkel and Trump don’t get on well together, and May has Brexit to deal with. Macron has become the “representative European,” and he has a personal rapport with Trump; this has also helped to keep Trump in check. But the two do get along, and according to Drozdiak Macron thinks it is in part because they were both “political outsiders who came in and blew up the establishment.” Nevertheless, Macron repeatedly confronts Trump, such as in his speech before a joint session of Congress last year, or this past weekend at the Armistice memorial, where he stated that “patriotism is the opposite of nationalism.”

Drozdiak said that domestically Macron is having some success. “Nobody thought he could take on the train drivers and actually win!” And many of the estimated 80,000 young French who went to Silicon Valley have come back to Paris to do start-ups. “There is a lot more going on in France than people realize.” Oddly enough, said Drozdiak, now that France is doing something active about reform, Germany is now criticizing its neighbor—even though it was Germany that has, for years, pushed France hard on further reforms.

Image courtesy US Joint Chiefs of Staff