Lose Your Tail

The following is the commencement speech delivered by American Academy fellow Josh Kun to Bard College Berlin’s graduating class of 2018.

What an honor to be here with you all, to be entrusted with offering words in connection with your commencement. I won’t lie, I’m nervous. It’s high pressure. Not just because this is such a special occasion, and that I think of commencement speakers as vaunted figures who are really wise and know how to impart that wisdom with uplifting aphorisms, but I am nervous because you are ending this important time in your lives and are on the brink of a commencement: a beginning, an opening-up into something new, a new identity, a new daily schedule with no classes, a new job, a new city, a new country, or for those lucky enough who want to be lucky enough, a return to a home, but a home that will inevitably feel new.

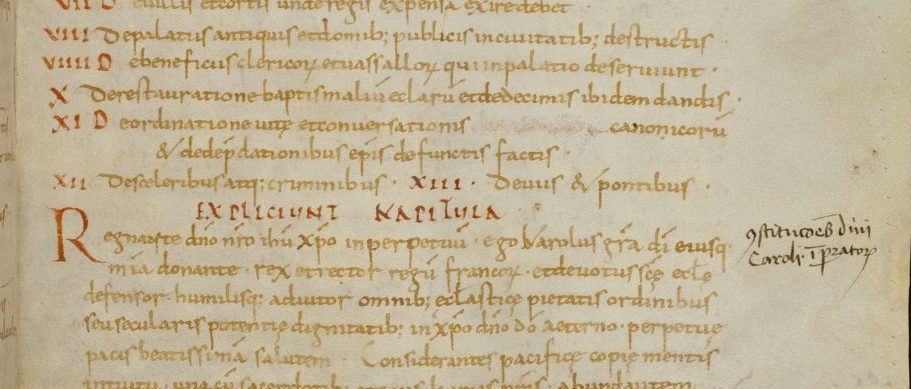

When the first commencement ceremonies began in universities and colleges, in the 1800s, commencement was chosen as a term because of this original etymological root in beginning—commencements were the ceremonies that marked the day that students “begin to be”—the day you are “made” as a Bachelor or a Master or the like. Today you begin to be this new you. Today you are made, made anew.

You are forever changed today.

But today is not over yet, the commencement is still commencing, you are not there yet—this is a threshold day, a liminal day, a transition day. You are standing at what the poet Stanley Plumley once called an “abrupt edge,” a term he borrows from ornithologists:

The border between two zones of vegetation…The advantage of the edge is that it allows the bird to live in two worlds at once, and the more abrupt the more intense the advantage. From a position of height or secrecy, the bird can spy for danger or prey; it can come and go quickly, like a thief. Here the vegetation is more varied, the shade and cover thicker; the insect life rising, the tanager can sweep down from its treetop, the thrush can fly out from the gloom, and the redwing can sit on the fence post all day in the summer sun. The edge is a concept of a doorway, shadow and light, inside and outside, room and world’s room, where the density and variety of the plants that love the sun and the open air yield to the darker, greener, cooler interior world, at the margin. It is no surprise, then, that the greatest number of species as well as individuals live at the edge and fly the pathways and corridors and trails at the joining of the juxtaposition. That is where the richness is, the thick, deep vegetable life—a wall of life, where the trees turn to meadows, the meadows to columnar, watchtower trees. A man of sense, coming to a clearing, a great open space, will always wait among the trees, in the doorway until the coast is clear.

Now, you are all people of great sense, and you have come to a clearing, a great open space. I urge you to wait among the trees. Stand in the doorway whenever you can. Take in the thickness, the richness of this deep vegetable life of the threshold, where your room meets the room of the world.

I came to Berlin in January at my own threshold, my own commencement, my own beginning to be—a new book, a new city, a new language. I came to a new country I never thought I would spend time in, a country where my great uncle and aunt met in a displaced persons camp after World War II, after surviving the death camp of Auschwitz. I came to Berlin with my wife, who has lived most of her life in Tijuana, Mexico, blocks from the border wall that when we first met, in the 1990s, had graffiti on it that read, “If the Berlin Wall could fall, why not this one?” Still a good question. Just two weeks ago, members of the Central American caravana migrante finished their journey north, right there where that graffiti once was. Migrants gathered against the steel pillars, and one young man climbed on top to sit on the wall long enough to get his picture taken but not long enough to be detained.

I also came to Berlin with our six-year-old daughter, who has inherited this mix of histories, this mix of traumas and displacements, this mix of walls and camps. Within her first month here, in a bilingual Kita, the two songs she came home singing were “No Roots”—a song about moving between homes by the daughter of a mining consultant, a Frankfurt-born, Canada, US, and Munich-raised singer Alice Merton—and “Keine Maschine,” by Berlin-based singer Tim Bendzko. In the video for that song, the young white German escapes a mysterious factory where workers all dressed in white are all, robotically, making the same photocopies. He breaks out, and goes on the run, first through a dark, damp forest, and then into the swells of a sea—geographies we are meant to recognize—forests of refuge, seas of flight. “I am no machine!,” he sings, “I am a human being of flesh and blood.” As I immersed myself in my own research on the arrivals of asylum seekers and forced migrants to Berlin and in the history of guest workers from Turkey and beyond—not to mention histories I already knew well, of forced camp labor and work that will most certainly not set you free—these songs were perfect introductions to my commencement in this city that has brought you to this moment of your commencement, this threshold, this moment of making, of beginning to be.

In my own work, I’ve praised this threshold experience as the art of the crossfade, a DJ term for moving back and forth between two different songs without choosing one over the other, and finding a way to mix them together without erasing them, finding the single point of connection, however microscopic, that they share, and using that single point to move between them. Slide the crossfader left, and one channel opens; slide it right, the other opens. For the DJ, the edges of songs, the transitions between them, is where the mix begins; it’s where the very art of DJing, of musical production lives: in the cuts, in the fades, in the thresholds, in the commencements.

I believe in the power of thresholds, in the rewards of the doorway, its possible refuge, its promised sanctuary, its utopia of what lies on the other side. I’m drawn to borders as places where identities and nations and languages cross and get confused. Borders are dialectical spaces, and even before spending time here in Berlin, I’ve been drawn to the great legacy of dialectical thinking that German thinkers produced in the early part of the last century—the importance of “introducing a difference into a discourse,” as George Didi-Huberman has put it, a confrontation between divergent opinions with a view toward arriving at an agreement that is mutually accepted. Brecht, Benjamin, Bloch, others all came back to the power of “bringing different points of view into confrontation around the same question.” In 1940, in exile in Finland before eventually returning to East Berlin after the war, Brecht asked us to consider the power of thresholds, of borders, and their inevitable discomforts, their dislocations and irruptions:

The best school for dialectics is emigration. The most penetrating dialecticians are people in exile. It is changes that forced them into exile, and they are only interested in changes. From the tiniest signs they deduce, so long as they are capable of thinking, the most fantastic events. They have an eye for contradictions. Long live dialectics!

Long live dialectics, indeed. But we must answer Brecht this way: And long live the bodies and minds in exile who do that dialectical thinking. Long live those forced to flee, those on the run, the uprooted, the dislocated. Long live those who took their own lives at borders, long live those whose lives were—and are, and are, and are—taken at borders, through fences, beneath walls.

All of us in this room, all of us in this city, all of us in this Europe, all of us in this contemporary world, also know that the crossroads, the border crossing, the border between cities, nations, cultures, and worlds can offer no refuge at all, but can be zones of great risk and great vulnerability, places of death. Doorways and thresholds and borders—sites of openings and closings, commencements and endings—can be dangerous. Just last week, I visited the Berlin Wall memorial site at Bernauer Strasse, and, like most who visit, I was taken by the site’s commemoration of this deadly and traumatic era of the past: death zones, checkpoints, walls, homes and families split in two, a city defined by its thresholds and doorways and edges. But I also thought about what the Berlin-based artist Trevor Paglen, riffing on Mark Twain, recently said in an interview: history rhymes. I looked at the guard tower and saw Gaza. I looked at the drawings of multiple fences and checkpoints and I saw Tijuana, Nogales, and Juarez. I saw flowers next to the black-and- white photographs of Germans killed trying to jump the wall and make it across that liminal zone between east and west, and I thought of the thousands who die in the Mexican desert each year. I thought of the nearly 100 Palestinians killed already this year in Gaza. In his novel about the Berlin Wall, Peter Schneider described it this way: “What on the far side meant an end to freedom of movement, on the near side came to symbolize a detested social order…for Germans in the west, the wall became a mirror that told them, day by day, who was the fairest of all.”

And so it goes.

Mirror, mirror on the wall.

In Berlin, wall-thinking may technically be history, but it’s still alive and well in different forms. In Hungary, where Victor Orbán has rejected liberal democracy for a “secure” “Christian democracy,” home to “the traditional family model of one man and one woman,” and called for preventions against the “settlement of alien population.” It’s alive and well in the United States, where, just two weeks ago, Attonery General Jeff Sessions stood at that same Tijuana wall and declared all asylum seekers criminals and promised to separate parents from their children, in the tradition of slavery, in the tradition of the Nakba. Days later, White House chief of staff John Kelly declared most immigrants crossing the border as unable to assimilate because they don’t speak English and come from rural villages. The walling legacy, the legacy of camp thinking, of course is also alive and well here in Germany too, wall or no wall—welcome culture, integration culture, B1, B2, C1, C2, assimilate or else—walls live on without the walls themselves. Who is German? Who is allowed to be German? Can a Syrian who comes to Germany as a refugee ever be German? What if you are in line in a bakery ordering bread in “broken German?” If you are Christian Lindner of the FDP party, “You can’t discern whether he is a highly qualified artificial-intelligence engineer from India or a foreigner who is being tolerated here illegally.” There is welcome culture, and it has been mighty and amazing in many ways, but as we have all seen, welcome mats soon can be stepped on, trampled, revoked, or torn up, or set on fire if the hosts decide they don’t want broken German, or don’t want foreigners interested in crossing the doorway on their own terms.

I recently spent an afternoon with one of your fellow Bard classmates, Anas Al Maghrabi, who arrived in Berlin from Syria, via Lebanon, Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, Serbia, and Croatia. When I visited his dorm room, I noticed he had too had a welcome mat, only it was on the ceiling not the floor, with a pair of shoes still attached. Sometimes welcome is not where you think it will be. Sometimes welcome is upside down, and we get stuck to it, never able to leave its bureaucracies and framings and classifications. Forever upside down.

I was struck when I arrived here to see that the Refugees Welcome stickers and posters all over Berlin and much of Europe included an image I know well from my home in Southern California: the silhouetted family of a father mother and pigtailed daughter running in mid-flight across borders and across the freeway. In Southern California, the image was not a welcome but a warning—it appeared alongside an interstate to warn drivers heading south to Mexico to not hit migrants who might be sprinting across the freeway in search of safety. The image was originally designed by a Native American Navajo artist, who was inspired by the 1864 deportation and attempted elimination of Navajos by the US government. The “Long Walk of the Navajo” took them away from their sacred land in Arizona and onto reservations in New Mexico.

History rhymes.

And so it goes.

Mirror, mirror on the wall.

To prepare for today, I went back to one of my favorite literary characters, Frankie Addams, the young girl who is the protagonist of Carson McCullers 1946 novel The Member of the Wedding. Frankie feels “unjoined”—she is an “I” person wondering what it means to belong to a “we”—wondering what it means to be a member of the world when the world is not a round globe that makes sense, but loose and wild and cracked, “and turning a thousand miles an hour. “All these people,” she thinks, “and you don’t know what joins them up. There’s bound to be some sort of reason and connection. Yet somehow I can’t seem to name it.”

I like the way Frankie thinks. That’s what I mean by thinking like a crossfader, thinking dialectically—in the face of ruptures, how do we work with the fragments of culture to produce new mixes, new montages, new orders of being, new kinds of commencement?

Since arriving in Berlin, I started the long process of learning Arabic. I wanted to take lessons to better understand the music I have been listening to and loving, and to better understand the musicians who make the music I have been listening to and loving. But in the process, I have also found the language to be full of lessons on connection and care across boundaries of self and other. For those in the audience who already speak in Arabic, this is not news to you, I know. When someone says “hello” to you in Arabic, it is not enough to respond with a “hello,” one should respond with two “hellos” back. If someone wishes you a “good morning,” a morning of well-being, sabah il-her, one responds not with a “good morning” back or even “good morning to you,” but with sabah in-nur, “morning of light.” When we connect, it is not enough to acknowledge or recognize, but to offer light where there was none. It is also there in the structure and rules of the language itself. In the formation of a word, only six Arabic letters do not change when they connect with letters to their left. All others change shape. As my teacher calls it, they “lose their tails.” In losing their tails, they are the same but different. To connect in order to become part of something bigger than a single letter, the letters must change. As you move through your own lives and move through your own work, this is an important lesson—as you connect, as you move outside yourself, you should want to lose your tails, change your shape. You will be the same but different, and you will be joined to something bigger than yourself. “Thinking,” Walter Benjamin once suggested (in a gloss by scholar Gerhard Richter) “a search for siblings…one who is related but different, related in difference.” But there is also thinking as a search for the unrelated, the stranger, the foreigner, unfamiliar, one who is different yet related—a letter that is not you, but a letter you need in order to make a new word. The difference that is required for you to be the same. To become part of something beyond ourselves—the words to our letters—we must lose our tails.

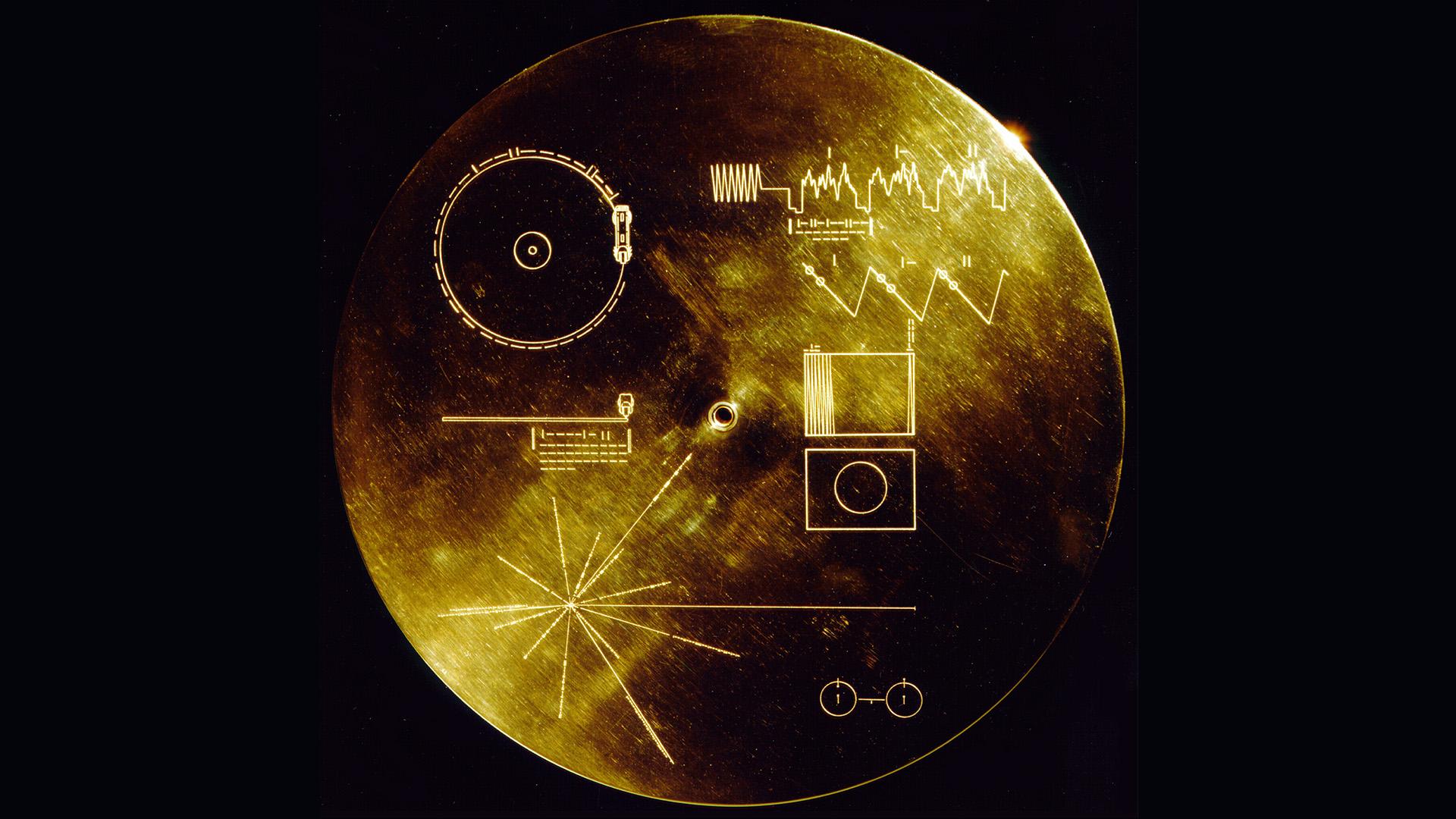

I realize that telling you to behave like Arabic letters might not be the rousing commencement-speech advice you were craving, so I’ll try one more in the spirit of connection, one I have already alluded to: think like DJs. When a DJ approaches a set or a mix, she is not thinking just about what songs she will play, she is thinking about what songs she wants to connect to each other and how she will do it. What musical moments connect Drake to Umm Kalthoum? When a DJ approaches a set or a mix, she is thinking, What story do I want to tell out of all these disparate elements? What narrative arc can be created out of these fragments? For the DJ, difference is the foundation of storytelling, the foundation of connection, the foundation of creating new spaces, new emotions, new movements. To think like a DJ is to think about the present and the future with the ear of a historian. To make a new mix, DJs need the past. They dig through the crates, they assemble sources, archives, citations. Know that the new work you will do will only be powerful, will only move you and move those around you, if it’s knowingly attuned to the past, if it is citational, if it has knowledge of history. To think like a DJ is also to think about what kind of new assemblies you hope to create. For a DJ, that assembly may be a dancing crowd, but for you it might be a circle of friends, a community you work with, an audience you hope to impact. As you think about your mixes, grounded in history but aimed for the present and the future, think about your publics, your audiences, the assemblies you hope to make possible.

To think like a DJ is of course to also think about emotions, feelings, about mood, and about movement—how will your work move others to move? How will it move into action? How will it move people into feeling differently or deeper about themselves? About the world around them? How will your mix bring a stranger joy? How will that joy connect you to someone you have never met before? How will that individual movement produce a collective movement that leads to a new horizon? In other words: make your own path through history and culture; put your own story on the fragments of life that are in front of you, the ruins of time, tell your own story against the backdrop of all those stories that have come before. The old songs will always be there. We need new songs that know the old songs well enough to keep loving them or leave them behind, new mixes that know that history rhymes and new publics, new assemblies, new friends, new dance partners—no matter how improbable or unexpected—are always possible if the music is right.

I realize this advice might already be obvious to you, a room full of young people from Denmark, Serbia, Spain, Germany, US, Georgia, Egypt, China, Norway, Czech Republic, and Palestine, who have all been living alongside one another, thinking alongside one another about everything from Ralph Waldo Emerson to musical dialectics, from climate change to historical monuments, from alternative Arab feminisms to Botticelli, Ovid, and NATO. You yourselves are a mixtape already in motion.

So put the needle on the record, cue up the next voice, the next beat, the next track of your lives. May it speak truth to power. May it posses what Gramsci famously called “optimism of the will and pessimism of the intellect.” May it love your neighbor. May it welcome a stranger, but on the stranger’s terms. May it look out on a cracked and broken world, a precarious and often monstrous and heartless world, and seek to heal it.

Be healers.

Be connectors.

Make the music of your lives.

(With thanks to Adi Yassin, Ussama Makdisi, and Rasha Hilwi)

Josh Kun is Director of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Southern California, where he is Professor and Chair in Cross-Cultural Communication. He was a spring 2018 Bosch Fellow at the American Academy in Berlin.

(Photo: Vera Yung. Courtesy Bard College Berlin)